A recent US case gives timid hope after unlimited attorney-client privilege in relation to tax cheating. But is this enough? Is the real issue being addressed?

We’ve paid a lot of attention to “enablers” – that is, the bankers, accountants, lawyers, and others who put together the system of global financial secrecy that underpins a world of crime and abuse. This was the theme of the Tax Justice Network’s 2019 conference.

Our main

concern is, why do we enable “enablers” to invoke and use laws and rights

conferred by society to protect criminals and tax dodgers that end up hurting society?

Putting the riddle more simply, why do

we protect a system that hurts us?

The enablers’

arguments against transparency are peculiar

The Tax

Justice Network opposes illicit financial flows, understood as funds of legal

or illegal origin (related to corruption, money laundering, the financing of

terrorism, tax evasion and a lot of tax cheating by multinationals) enabled by

secrecy jurisdictions and their enablers.

The enablers, however, regularly oppose our opposition. But their arguments typically come in the form of riddles. Here’s one.

When we say,

“We estimate that the scale of the problem (illicit financial flows, tax

avoidance, etc) is $X trillion.”

Banks, the Big

Four accounting firms, or other holders of secret information often respond, “Your

numbers are wrong: you know nothing.”

So we

answer, “Well, our numbers are just estimates because you keep all the data

secret. Publish the data and prove us wrong!”.

They respond,

“Why would we listen to you or do what you ask, if your numbers are wrong? You

know nothing.”

So we are

“wrong” because we don’t have access to the data being kept secret, but we

cannot get access to the data because our “wrongness” prevents us from requesting

it. That’s a classic Catch-22.

We’re supposed to take the word of enablers who may be abetting criminal activity, who claim that “all the money held in this bank, or country, or freeport, is of legal origin, from honest people and we have complied with all laws”. We are expected to believe them, even after the Panama Papers, Paradise Papers, LuxLeaks, Swiss leaks, and now Mauritius Leaks continue to confirm our assessments.

Another common ruse is to invoke arguments about protecting the sick and vulnerable as justifications for activities that shield criminals or the very rich from the rule of law.

For

instance, when we call for more transparency on trusts, the enablers respond:

“No, trusts are private family matters. They are used to protect sick and

vulnerable people, children and spouses after the settlor dies.” One lobbying organisation went so

far us to attack us

for putting “Jews in France, or homosexuals in Saudi Arabia” at risk by

threatening their privacy. To which we

replied:

Really? We are not aware of a single transparency campaigner, street protestor, anti-corruption campaigner, trade union official, investigative journalist, or dissident of any kind who has been protected from oppression by virtue of having a secret bank account or offshore trust. On the contrary, we can name any number of their oppressors – Augusto Pinochet, Obiang Nguema or Sani Abacha come to mind here – who use and have used secrecy jurisdictions extensively to preserve their power and wealth at the expense of their millions of victims.

Lawyers and

lobbyists whose fees are unaffordable to most vulnerable people, invoke the

rights of vulnerable people in order to oppose transparency of trusts, often for

the benefit of people who may be oppressing or cheating the vulnerable. Let’s

face it: there is ample evidence of trusts being used by dictators, corrupt

officials and money launderers, rather than the sick and vulnerable (see our briefing paper on trusts and our follow up paper). Perhaps most commonly, we see trusts used by wealthy husbands to

rip off ex-wives in divorce proceedings.

Similarly,

when we ask for public beneficial ownership registries for companies and other

legal vehicles in order to find out who are the individuals that ultimately own

and control them, we are told this creates unnecessary red tape and that it will

lead to individuals being kidnapped or subject to violence. However, it’s the lack

of beneficial ownership transparency that allows corrupt officials, drug smugglers

and other money launderers to infiltrate and corrupt the economy and politics

of a country, creating instability and violence. Most honest people who own

shares in a normal company have nothing to hide and don’t need complex offshore

structures. They directly own their shareholdings (so their information is often

public in many countries with basic commercial registries.)

Attorney-client

privilege: is transparency finally making its way against enablers’ last

defense?

The basic financial

secrecy strategies to engage in illicit financial flows usually involve a

corporate service provider helping a client set up secretive companies or

trusts, and using these to open secret bank accounts or hold unregistered assets

in tax havens that don’t exchange information, so that the identity of

criminals and their wealth will remain hidden from local authorities. The

ultimate defense, however, is when the corporate service provider (who created

the secretive entities to own the secret bank accounts in a secrecy

jurisdiction) is actually a lawyer who prevents any cooperation with

authorities by invoking attorney-client privilege: the confidential status of

communications, strategies and documents related to a defense attorney and

their client.

However, transparency has been creeping in, step by step.

For

instance, banks have a contractual (and sometimes legal, or even constitutional!)

obligation to their clients not to disclose their bank account information, so

as to protect client privacy. However, this privacy principle clearly clashes

with other principles, such as the need to combat illicit financial flows and

financial crime. And in fact, it is now increasingly accepted that this latter

principle should predominate. Given that banks have such a pivotal role in

enabling financial crimes, in many countries they now have to routinely report

information to local authorities, including for purposes of automatic exchange

of information across borders.

There has

been progress also in another, related area. Setting up companies without

disclosing any information on their owners used to be commonplace. However,

there has recently been progress when It comes to the transparency of companies and trusts, with

some countries requiring that the beneficial owners of companies and trusts

(the real individuals who ultimately own and control and benefit from these

legal vehicles) be registered. In some cases, like the European Union’s amendment to the

4th Anti-Money Laundering Directive, beneficial registries will be made

publicly available

– something we started calling for years ago.

Despite

this progress, corporate service providers (eg nominee directors who on paper

are supposedly administering thousands of companies) continue to pose risks.

The biggest threat is when these service providers are lawyers and shield themselves

behind the cover of attorney-client privilege as if they were defending their

clients in court.

The

Financial Action Task Force’s (FATF’s) 2013 report “Money Laundering and Terrorist

Financing Vulnerabilities of Legal

Professionals”

confirmed:

“[the] perception sometimes held by criminals, and at times supported by claims from legal professionals themselves, that legal professional privilege or professional secrecy would lawfully enable a legal professional to continue to act for a client who was engaging in criminal activity and/or prevent law enforcement from accessing information to enable the client to be prosecuted.”

Attorney-client

privilege is certainly necessary for society to ensure a fair trial, in the

context or threat of a trial.

But this

doesn’t mean that literally anything a lawyer does with their client should

enjoy this privilege. It should not allow a lawyer to stay above scrutiny or

the rule of law, especially when acting as a corporate service provider or

nominee director, or when designing schemes to allow individuals and companies to

cheat on their taxes or commit other financial crimes.

But this

line is usually blurred. On the one hand, the Financial Action Task Force’s Anti-Money Laundering

Recommendation 23

requires lawyers to report suspicious transaction when, on behalf of or for a

client, they engage in buying and selling of real estate managing client money,

securities or other assets; managing bank accounts, savings or securities

accounts; creating, operating or managing

legal persons or arrangements; and buying and selling of business entities. On

the other hand, however, the Financial Action Task Force’s Interpretative Note to

Recommendation 23

establishes:

Lawyers, notaries,

other independent legal professionals and accountants acting as independent

legal professionals, are not required to report suspicious transactions if

the relevant information was obtained in circumstances where they are subject

to professional secrecy or legal professional privilege.

It is for each country to determine

the matters that would fall under legal professional privilege or professional

secrecy.

This would normally cover information lawyers, notaries or other independent

legal professionals receive from or obtain through one of their clients: a) in

the course of ascertaining the legal position of their client, or b) in

performing their task of defending or representing the client in, or concerning

judicial, administrative, arbitration or mediation proceedings. [emphasis added]

Based on

these ambiguities, it’s no surprise that the Financial Action Task Force’s “Money Laundering and Terrorist

Financing Vulnerabilities of Legal Professionals” report concluded:

It is apparent that there is significant diversity between countries in the scope of legal professional privilege or professional secrecy. Practically, this diversity and differing interpretations by legal professionals and law enforcement has at times provided a disincentive for law enforcement to take action against legal professionals suspected of being complicit in or wilfully blind to ML/TF activity.

This is

also reflected in the poor performance by major countries in complying with the

Financial Action Task Force’s anti-money laundering recommendations. The Financial Action Task Force’s assessment on Recommendation 23 (which includes the

requirement for lawyers to file suspicious transaction reports) has the

following ratings, which go from “non compliant”, “partially compliant”,

“largely compliant” to “compliant”. As of April 2019:

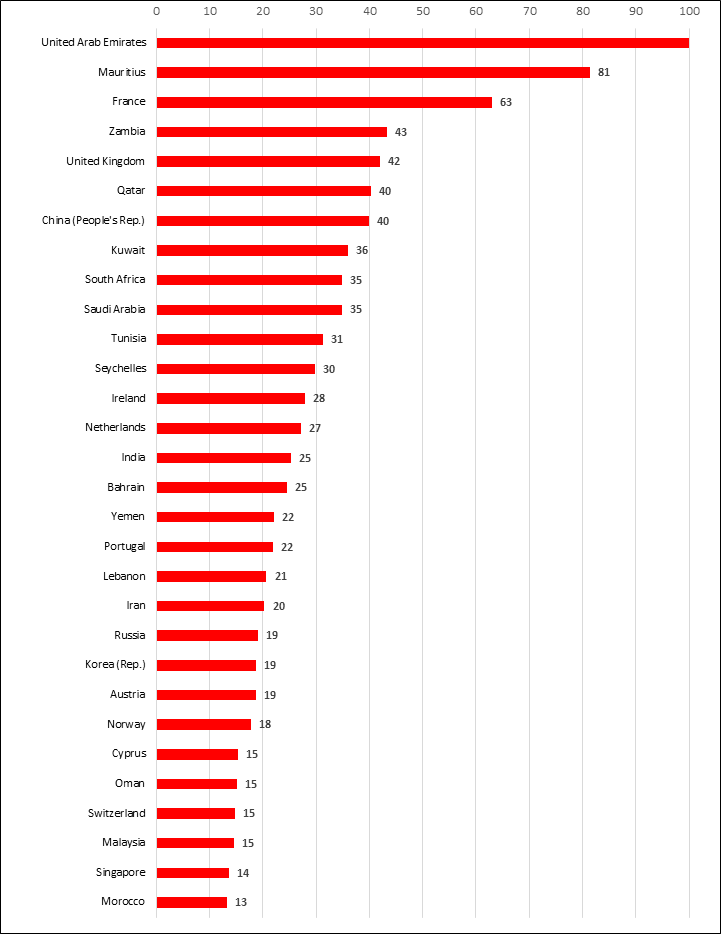

“Non-compliant”

countries include among others: Australia, Canada, China, Mauritius, and the United States.

“Partially

compliant” countries include among others: Barbados, Cayman Islands, Isle of Man,

Singapore and Switzerland.

A recent US

case, however, brought some hope on the limitations of attorney-client

privilege, when a law firm was required to hand in list of clients that could

have used a scheme to evade taxes. In the recent case Taylor Lohmeyer Law Firm PLLC v.

United States of America, Civil Action No. SA-18-1161-XR, 15 May 2019, the US tax authorities (the

Internal Revenue Service) were granted access to certain information related to

the clients of the firm including the clients’ names.

The real

challenge: authorities, enablers and confidentiality

The fact that US authorities were granted access to the list of clients of a law firm may sound like a big step for transparency. But it’s definitely no giant leap for humankind, or big advance in the fight against financial crime.

While narrowing attorney-client privilege in the fight against illicit financial flows is relevant, it would be rather foolish of us to think that the battle finishes there. There will always be another corrupt official, money launderer or tax cheat. The only real way to deal a hammer blow to the system is to take on the system: the private enablers.

In fact,

when looking at the US case, if the only thing US authorities got from the law

firm was a list of clients, this would then be a rather “pyrrhic victory”, aka

not that great really, when considering what the

Internal Revenue Service described

to be the role played by the law firm and some of its lawyers:

The IRS [Internal Revenue Service] previously audited a taxpayer (Taxpayer-1) who used the Firm to “set up foreign accounts, foreign trusts, and foreign corporations to avoid paying U.S. taxes for which he was liable… the IRS seeks names of and other information related to the Firm’s clients between 1995-2017 to investigate the tax liability of those who used the Firm to “create and maintain foreign bank accounts and foreign entities that may have been used to conceal taxable income in foreign countries.”…

An interview with John Taylor, former partner of the firm, Taylor estimated that he structured offshore entities for tax purposes for 20 to 30 clients between the 1990s and early 2000s…

Taylor Lohmeyer PLLC’s services to their U.S. clients, as described by Taxpayer-I and Taylor himself, are the kinds of activities that, in the experience of the IRS, are hallmarks of offshore tax evasion, including: (1) structures of offshore trusts with compliant trustees, and foundations and anonymous corporations managed by nominee officers and directors, (2) the use of “straw men” to contribute nominal funds to foreign trusts to create the false appearance that such trusts have foreign grantors, and (3) the concealment of beneficial ownership of foreign accounts and assets in jurisdictions with strong financial secrecy laws and practices.

The information obtained by the IRS and discussed in this Declaration suggests that the still-unknown U.S. taxpayers doing business with Taylor Lohmeyer PLLC may not have reported their offshore accounts, entities, or structures. Instead, they have likely relied on the assistance of Taylor, and the fact the structures are hidden offshore to support a decision not to report the existence of those entities and accounts, expecting that the IRS would not discover the accounts, omitted income, and/or the existence of the entities. [emphasis added]

A case from

Canada is even more outrageous, when considering that confidentiality took

place between the tax cheaters and authorities, against the wider

public.

In 2015, CBC Canada reported on a case brought by the

Canadian Revenue Authority (CRA):

KPMG has been fighting a court order to provide the list of names of multi-millionaire clients who had used what the CRA has alleged in court documents is a “sham” Isle of Man tax avoidance structure. The court file, which had seen virtually no activity for much of that time, had remained mysteriously stalled…

Last July, KPMG lawyers told the court they were having confidential discussions with the Department of Justice on behalf of the minister of national revenue to settle the matter out of court…

One might

expect the authorities would fight until they obtained the full list of all

those who used the tax cheating structure, to prosecute them. After all, CBC also reported:

The Trudeau government’s previous tough talk on the so-called sham had come after a document leaked to The Fifth Estate/Enquête showed the CRA itself had offered a secret “no penalties” amnesty in May 2015 to many of the KPMG clients involved in the scheme…

But in 2019

CBC reported that the CRA had signed a secret

settlement with KPMG clients caught in the case:

The CRA cites privacy in keeping settlement details secret… ‘there is generally substantial savings to the public and a benefit to the justice system when cases are resolved through a settlement,’ a CRA spokesperson said in a statement.

So, what’s

the response to the public outrage after a leaked document revealed “no

penalties” amnesty for those involved? A secret agreement — and Canadians

must, apparently be grateful that it’s secret!

Again,

invoking the rights of the many to protect the few.

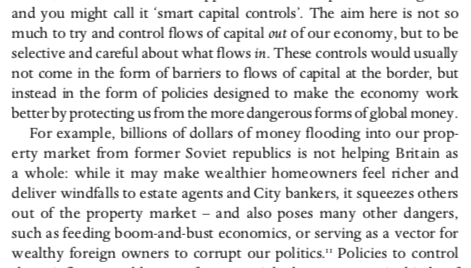

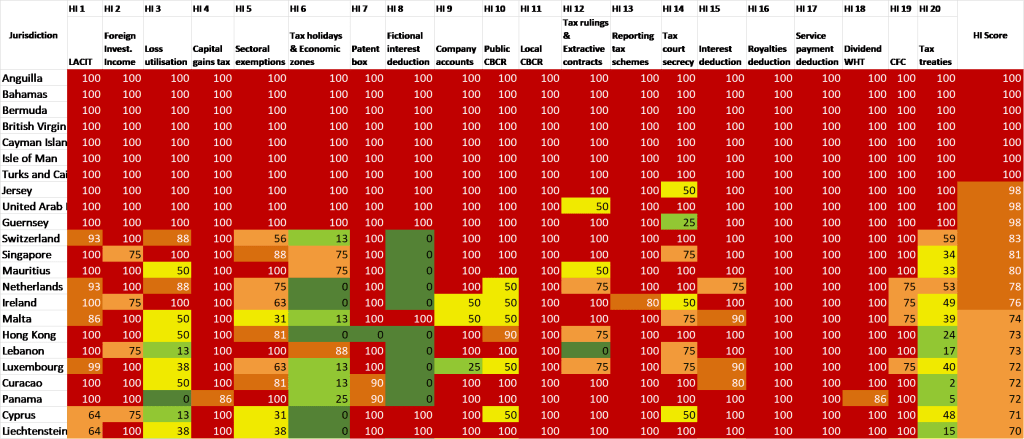

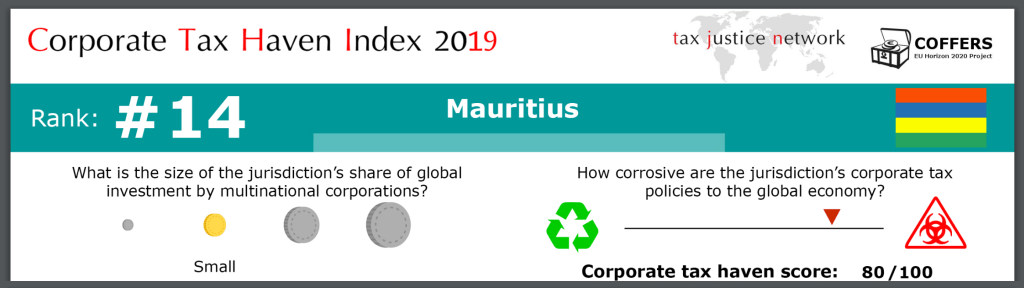

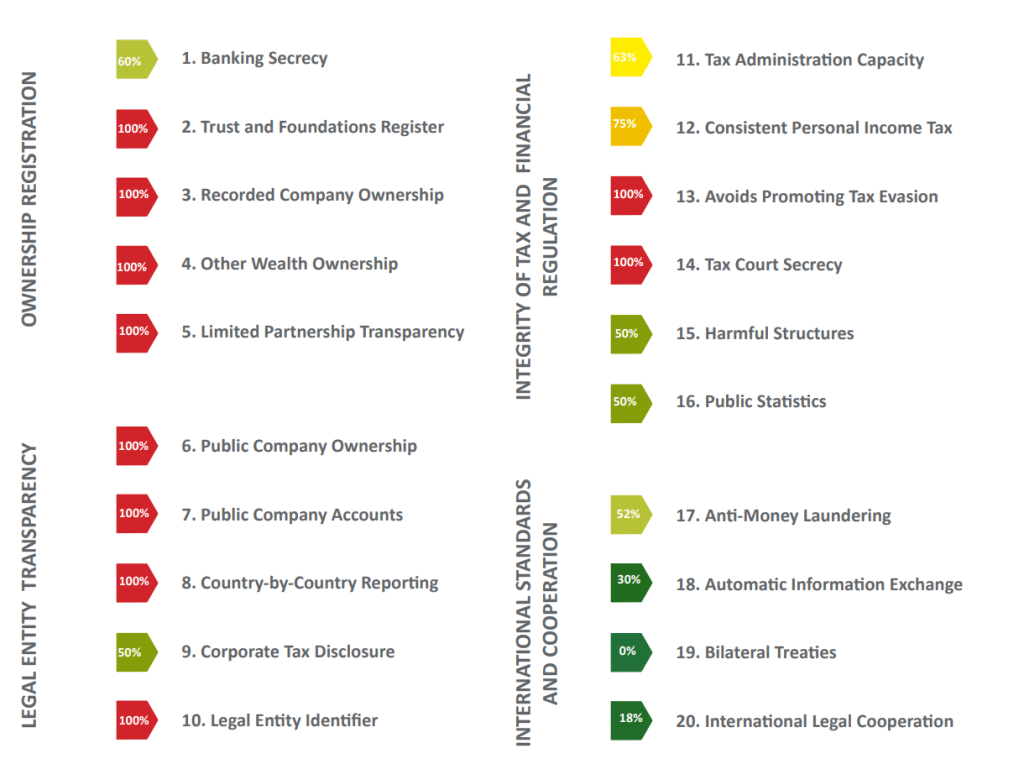

In this context, our recently published Corporate Tax Haven Index, which complements our Financial Secrecy Index, provides some useful pointers for reform. Both indexes assess, among other things “tax court secrecy” in countries to find out whether tax court proceedings and verdicts are open to the public. The Corporate Tax Haven Index also looks into secret tax rulings, such as the ones outlined in the LuxLeaks scandals.

But similar

to the US case, this Canadian case shows that the problem is much larger than

just the secrecy.

CBC Canada continued:

Documents show KPMG planned to take a 15 per cent cut of the taxes dodged, including $300,000 from the Cooper family. Internal records show the scheme was marketed across the country, with successful KPMG sales agents and accountants referred to as product “champions.”

…Documents had already begun to emerge detailing the extent to which KPMG was helping clients not only dodge taxes but also hide money from potential creditors, including circumventing the Canadian Divorce Act by “protecting” assets from ex-spouses…

In light of

this, we couldn’t agree more with Dennis Howlett, executive director of

Canadians for Tax Fairness, who actually said back in 2015 in relation to

Canada’s case, as described by this CBC article:

At this point, the court case is only really about KPMG releasing the names of their clients but the real point of it should be to get evidence needed to take KPMG to court for facilitating aggressive tax planning.

Why

don’t authorities go against enablers?

It’s not

clear. Have they captured the State? Is corruption involved, to protect elites? Resource constraints?

The Financial

Action Task Force’s “Money Laundering and Terrorist

Financing Vulnerabilities of Legal

Professionals”

report summarised two main reasons (based on responses from countries) on why

“legal professionals were not charged with the criminal offence of money

laundering although it was clear to the investigating officers that they were

involved in the money laundering activity”.

The first one suggests it’s a problem of resources:

Firstly, because of the inability to secure sufficient evidence to prove their complicit involvement in the money laundering schemes. Domestically, access to evidence may have been refused because claims to legal professional privilege or professional secrecy were upheld; or investigators decided not to pursue that evidence because of the more complicated processes involved in seeking access to such evidence and demonstrating that it is appropriate to be released. In the case of an international investigation, the evidence-gathering process can be hindered by the fact that privilege and secrecy varies across the countries that are trying to cooperate.

The second

reason is far more problematic because it suggests that authorities would

rather use enablers as cooperators rather than going against them, hoping that

the reputational risk will be enough of a deterrent:

Secondly, because they are likely to make useful co-operators, informants, and/or cooperating witnesses. A legal professional has every incentive to co-operate with law enforcement once his/her illegal activity is discovered to avoid reputational harm, loss of license (livelihood), and censure by the bar.

In any case, the only thing that’s clear is that unless enablers are stopped, business will go on as usual. Society will keep getting hurt, and they will keep telling us that it’s for our own good.

Requiring all tax court verdicts and tax rulings to be placed on online public record would be a great start, a first reputational deterrent against this kind of collusion of the few against the many.

Second, countries should coordinate to narrow attorney-client privilege to situations involving the defence of a person before a court, but require full cooperation and reporting of suspicious transaction reports from lawyers who are acting as corporate service providers or nominees.

Lastly, governments should properly resource their tax authorities and prosecutors to ensure they will not be afraid of going against enablers.

Treating enablers of illicit financial flows as witnesses and friends of the justice system is like asking a drug kingpin to testify as a witness against a penniless dealer that sells drug on the street. It should be the other way round.