Rachel Etter-Phoya ■ How can Africa take action against corporate tax havenry? Solutions from the Corporate Tax Haven Index 2019

How have former colonial powers maintained their stranglehold on African economies? The UK with its spider’s web of satellite jurisdictions and France are complicit in undermining the ability of African governments to tax multinational companies. Other corporate tax havens also put African countries at risk.

The Corporate Tax Haven Index, published last month by the Tax Justice Network, reveals how the UK and a handful of other OECD countries are most responsible for the breakdown in the global corporate tax system. Globally, $500 billion in corporate tax is dodged each year. In Africa, estimates suggest that as much as $50 billion is lost annually through illicit financial flows. Across the African continent, multinational companies are extracting resources, selling products and using labour, but often they’re paying far too little tax.

Global corrosive corporate tax havenry

The new Corporate Tax Haven Index identifies the most corrosive corporate tax havens in the world as the UK, the Netherlands and Switzerland. The UK with its network of overseas territories and crown dependencies is responsible for over a third of corporate tax avoidance risks.

These corporate tax havens ruthlessly undermine the ability of governments to tax multinational companies. This means ordinary African citizens have to pay more taxes on personal income, on basic food items and on services since the most vulnerable in society end up shouldering the biggest burden of taxation. African nations may also be forced to borrow money or rely on aid from some of the very same corporate tax havens that are lining their pockets as a result of tax avoidance.

France and the UK are identified in the Corporate Tax Haven Index as the most aggressive OECD countries towards low-income and lower-middle income countries. France secured some of the largest reductions in withholding tax with its former colonies Burkina Faso, Niger and Togo. Withholding tax allows countries to deduct tax on royalties, dividends, interest or other payments made by subsidiaries to companies or individuals outside the country.

Over one-third of inward foreign direct investment in African countries is in partnership with the top 10 countries in the Corporate Tax Haven Index, those same countries that have done the most to proliferate corporate tax avoidance and break down the global corporate tax system.

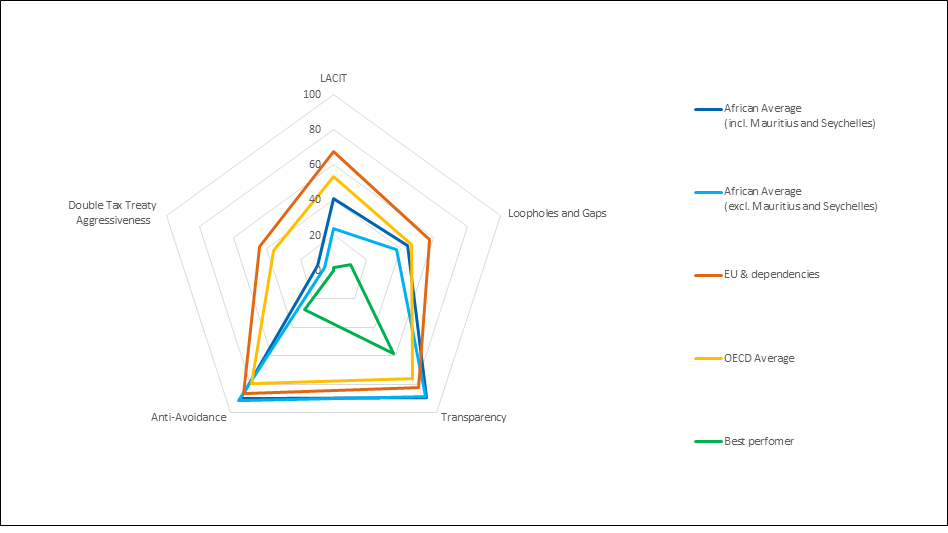

The Corporate Tax Haven Index meticulously evaluates the tax system of each country by looking at its laws, regulations and documented administrative practices. The twenty haven indicators are spread across five categories: the lowest available corporate income tax offered, loopholes and gaps in a country’s tax system, such as tax exemptions and tax holidays, transparency in corporate reporting, tax rulings and avoidance schemes, anti-avoidance measures in place and the aggressiveness of double tax treaties.

Based on the haven indicators, the index gives each country a score on how much its tax system enables corporate tax avoidance and then combines that score with the amount of corporate activity taking place in the country in order to determine how much corporate activity is being put at risk of tax avoidance. The greater the share of the world’s corporate activity jeopardised by the country’s tax system, the higher the country ranks on the index.

Of the 64 countries included in the index, nine are African countries, and the world’s most well-known corporate tax havens and major financial centres. For all countries, a detailed scorecard is available on each of the 20 haven indicators: Botswana, Gambia, Ghana, Kenya, Liberia, Mauritius, Seychelles, South Africa and Tanzania.

Aggressive tax treaties

Even though no African countries feature in the top 10, we still need to watch out for the race to the bottom in tax rates between African countries. Mauritius, for example, exposes many African countries to corporate tax avoidance through double tax agreements with its lowest available corporate income tax of 0%. The agreement signed between Senegal and Mauritius is one of the most aggressive – no withholding tax on dividends, interest or royalty payments.

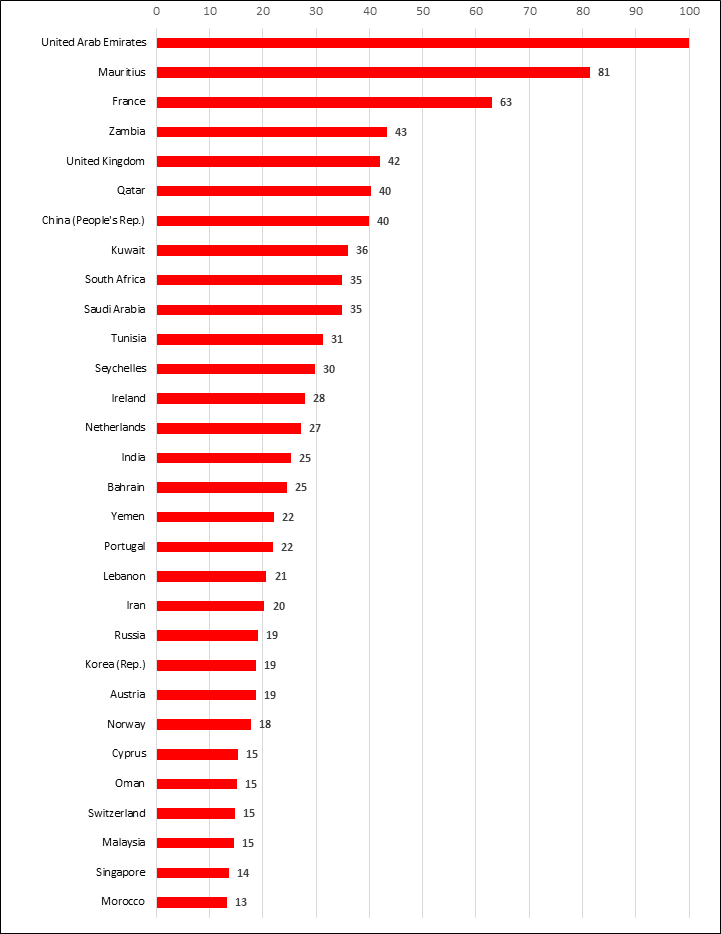

The chart below demonstrates how the former colonial powers France and the UK continue to negotiate aggressive double tax treaties with African nations. Yet even they are surpassed by the United Arab Emirates and Mauritius, which have negotiated the greatest withholding tax reductions with African countries.

Despite evidence that the tax treaties signed by African nations result in revenue loss rather than additional investment, African governments continue to put pen to paper and lock their citizens into destructive deals.

On the launch of the Corporate Tax Haven Index, Alvin Mosioma, Executive Director of the Tax Justice Network Africa, has once again questioned the Kenyan government’s decision to re-sign a tax treaty with Mauritius. President Uhuru Kenyatta signed the agreement with Mauritius in April 2019 just after a court ruled that an earlier agreement was invalid, following Tax Justice Network Africa’s petition:

It is unacceptable that the Kenyan government is shifting the burden of taxation to the ordinary citizen, while deliberately opening doors for the wealthy elite and unscrupulous MNCs [multinational corporations] to evade and avoid taxes through DTAAs [Double Taxation Avoidance Agreement] with secretive tax havens.

Alvin Mosioma, Executive Director of the Tax Justice Network Africa

Action at home against corporate tax havenry

The individual policy categories and indicators in the Corporate Tax Haven Index reveal concrete policies and steps African nations could take at home in order to address tax avoidance across all sectors.

As the chart above shows, in comparison with countries and their dependencies in the OECD and the European Union, African nations have less aggressive treaty networks, have protected higher corporate income tax rates and have fewer loopholes and gaps in their taxation systems that encourage profit-shifting activity and the race to the bottom in corporate taxation. Nevertheless, African countries show a high presence of tax exemptions and holidays and in the categories of anti-avoidance and transparency, African countries have room to improve.

Improvements in transparency can assist African tax administrations in prioritising and conducting audits of multinational companies with local subsidiaries and indeed build trust with citizens. This includes taking steps like requiring all companies to submit accounts and for these to be freely available online, to file country-by-country reports locally and to report tax avoidance schemes or uncertain tax positions. Public access to information is vital to things like tax courts and decisions, and any unilateral tax rulings issued and contracts for mining and petroleum projects should all be freely accessible to the public.

Anti-avoidance measures can also be improved to reduce the risk of base erosion and profit shifting. Robust controlled foreign company rules and withholding taxes on outbound dividends can act as a barrier to shifting untaxed profits to secrecy jurisdictions and zero corporate tax havens. Deduction limitation rules could be introduced or strengthened to prevent multinationals from deducting interest, royalties and certain service payments from their tax base if paid to other subsidiaries of the same multinational. Any upcoming trade agreement on the African continent should ensure that such defensive measures remain compatible with the trade regime and regulations. The Rwandan example of limiting the deduction of outbound royalties is a case that warrants close examination by African peers. At the same time, African nations should withstand the temptation and false lure of introducing patent box regimes themselves and consider appropriate reactions to countries that do, including Botswana, the Seychelles and Mauritius.

A key area of improvement in the loopholes and gaps category in the Corporate Tax Haven Index can be achieved by addressing tax incentives. African governments have granted many sectoral exemptions and tax holidays. These profit-based incentives are costly and, contrary to popular opinion, they usually fail to attract additional desirable direct investment as shown in the Tax Justice Network’s study of incentives in Ghana, Kenya, Liberia, Tanzania and South Africa. Governments would be far better off raising taxes to pay for better roads and energy provision, since enabling conditions like good infrastructure, the rule of law and macroeconomic stability are more decisive for investors than tax incentives and a prerequisite for ensuring investment schemes are effective. This is shown time and again in investment climate surveys for low income countries.

Uniting behind the unitary approach

Corporate tax avoidance is a global problem that requires global solutions and action. Domestic reform will only go so far since the Corporate Tax Haven Index suggests that so far Africa is less engaged in the ruinous race to the bottom in corporate taxation than countries in the OECD and the European Union. The overarching solution that has gained some ground recently with the International Monetary Fund and the Tax Justice Network has been advocating for years is the unitary tax approach.

The unitary approach treats a multinational corporate group as a single entity. This means that total global profits would be allocated – or apportioned – to the countries where the company does business in proportion to genuine economic activity carried out by each subsidiary. In this way, corporate tax havens where there is little or no genuine economic activity would be cut out. Instead countries where the resources are extracted or where significant staff are employed, for example, will be able to tax the share of global profits. This approach would allow African countries to raise the taxes that are rightly theirs to achieve the sustainable development goals, reduce reliance on aid and address inequality.

During the OECD’s consultations on the best way to tax in the digital economy, unitary taxation with formulary apportionment has become the leading alternative to the arm’s length approach. African nations along with other lower to middle income regions need to remain alert and resolute in these discussions because they will have ramifications for taxation in all sectors, and hopefully lead to greater taxing rights and revenue. A good performance on the indicators of the Corporate Tax Haven Index helps in ensuring that a broad tax base is supported in any future shift towards unitary taxation, such as by including capital gains and investment income in the tax base, and by constraining tax loss carry backward or forward provisions.

Take a look at the Corporate Tax Haven Index to identify how your country’s revenue and resources are exposed to corporate tax avoidance.

Related articles

What Kwame Nkrumah knew about profit shifting

The last chance

2 February 2026

The tax justice stories that defined 2025

Let’s make Elon Musk the world’s richest man this Christmas!

2025: The year tax justice became part of the world’s problem-solving infrastructure

Bled dry: The gendered impact of tax abuse, illicit financial flows and debt in Africa

Bled Dry: How tax abuse, illicit financial flows and debt affect women and girls in Africa

9 December 2025

The myth-buster’s guide to the “millionaire exodus” scare story

Quite insightful.How do we arrest the trend where the local elite conspire with the MNCs to exploit the tax arbitrage? A lot of locally owned conglomerates in Nairobi have opted to book/situate their royalties & dividends from investment entities in most tax havens, mostly in Mauritius.Yet the local elite also suffer for the lapses in governmental services delivery. I can draw a connection to the incremental medical tourism to India by Kenyans when we have stashed all rewards in Mauritius. What a tragedy.