Update, March 7: In new Zogby poll, majority of New Yorkers support the change. See TJN release here

A version of this document is being submitted today to the New York State Assembly, in support of its Stock Transfer Tax.

The time for financial transactions taxes has returned

By James S. Henry, John Christensen, David Hillman and Nicholas Shaxson

New battles with global finance are brewing, as a range of countries, states and coalitions now push to enact new financial transactions taxes (FTTs,) an old, honourable, effective and progressive kind of tax that is fast regaining popularity around the world as governments scramble to pay for the costs of the Covid pandemic. Powerful new initiatives in the United States and the European Union show rising momentum for new FTTs.

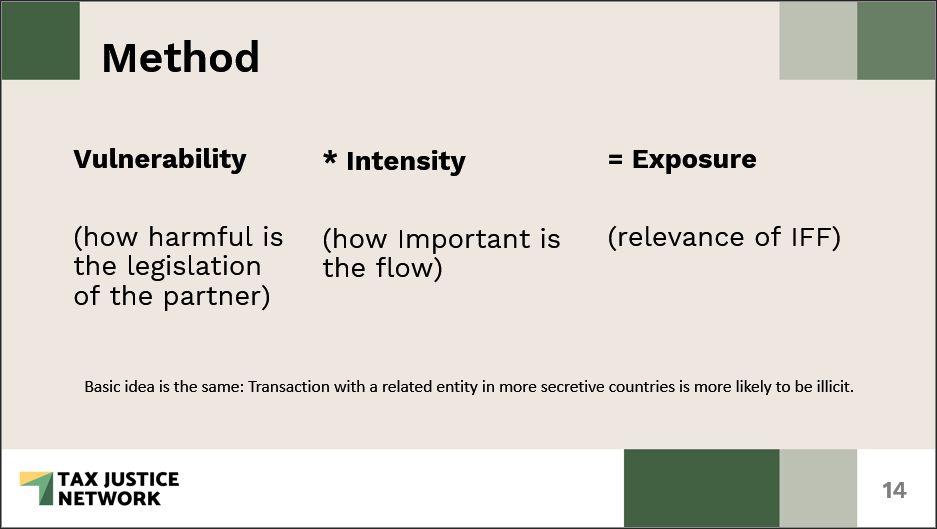

An FTT does what it says on the tin. States apply a tiny tax rate (for example, 0.1 percent) on the value of financial transactions such as the sale of shares or derivatives. Well designed FTTs have three main benefits: first, they raise significant tax revenue, delivering a welcome transfer of wealth from rich to poor; second, perhaps more importantly, they curb excessive and harmful high frequency financial speculation (which makes up around half of all US stock market trading now) while leaving normal trading and investment intact; third, they boost transparency, giving tax authorities better oversight of financial activities.

A push in New York, and the United States

In New York state, Assemblyman Rep. Phil Steck has sponsored a disarmingly simple three-page bill that would raise some $10-20 billion a year from Wall Street and plough the money into the pandemic response and the local economy, creating jobs with a fair, efficient and progressive tax.

The form of FTT in play is the Stock Transfer Tax, a tax on share dealing that has been on the books in New York state since a Republican governor introduced it in 1905 – and still is. The tax was progressive and highly effective, raising around $80 billion (in 2020 dollars) until 1979 when the New York Mayor and state governor caved into Wall Street pressure and phased in a 100 percent annual “rebate”, which unfortunately also remains in effect. So the tax is in effect levied – then kicked straight back to Wall Street. According to detailed calculations by co-author James Henry, who is helping Steck organise the fight, New York state has lost $344.2 billion in lost STT revenues since 1979 when they started phasing in the rebate (figure is in 2020 dollars: original data sources are here and here.)

“The whole public sector has been starved,” said Steck.

His bill is clear and simple: it removes the rebate. If enacted, it would levy a tax of five cents on every share trade valued over $20 – so for the median Nasdaq share traded, worth $48, this would amount to an insignificant 0.1 percent tax. It behaves like a progressive sales tax, vastly lower than the eight percent tax New York residents pay on retail items.

The STT would be painless and easy to implement – and, of course, would prove immensely popular. Steck’s bill currently has 54 sponsors in the New York assembly – and it only needs 60-65 to get accepted. (Senator James B. Sanders, Chair of the New York State Banking Committee, is sponsoring the same bill in the state Senate.) It has widespread support, ranging from the biggest trade unions, to conservatives worried about budget deficits. We are close to a nifty victory that can be replicated all over the planet. This has got legs.

A similar Wall Street Tax Act, a new federal FTT proposal, is supported by a good majority of voters, though its chances at a federal level are currently slim, and even lower if this doesn’t pass in New York. Various other FTT proposals have been introduced recently in the US alone.

The Wall Street pushback

Predictably, Wall Street is shrieking, and wielding the same kinds of spurious arguments and empty threats they always make when faced with taxes and regulations. For instance, the Securities Industry & Financial Markets Association (SIFMA,) in partnership with the Institute of International Bankers and several others, just organised a letter to Governor Cuomo opposing the STT, and the president of the New York Stock exchange followed this up by a thundering opinion article in the Wall Street Journal. These lobbyists wheeled out the usual arguments: that the tax threatens jobs; that it is a ‘tax on working families’; and of course the old “competitiveness” shibboleth: that all the banks will run away if they have to pay the tax. They cited various horror stories of countries like Sweden that had imposed an FTT, and apparently ended up regretting it.

They coo that the state should instead fill its current $15 billion pandemic-year’s fiscal deficit with other, complex mostly pro-Wall Street proposals that gouge the poor – such as budget cuts, raising fees on auto registration, or legalising casino gambling or marijuana. None have the clout and simplicity of simply repealing the costly rebate.

These tired old arguments remain as invalid as they have always been – as we will demonstrate below. Parts of our counterargument may shock some people.

A new push in the European Union

In the European Union, a new FTT push has just begun under the leadership of Portugal, which holds the rotating presidency. Although negotiations have been long and hard, Portugal has provided invaluable technical expertise on the FTT file over the years, putting it in a good position – with sufficient determination and strong civil society support – to deliver a historic FTT agreement in the coming months.

An EU document leaked to the Agence Europe highlights the FTT’s potential, and urges European countries to build on “an FTT that has already been successfully introduced and secured with minimal distortions to the financial markets” in France and Italy, and to “start testing at the European level, as early as possible, the approaches developed and already tested” – possibly including not just shares but equity derivatives. And, once introduced, it urges exploring “the options of developing this tax in the future”.

This gradual, phased approach may feel slow for those demanding a far more ambitious FTT, encompassing bonds and derivatives, but may be pitched correctly for now, so as to get the FTT over the line at a time when European leaders know their populations, angry and hurting, demand measures like this.

In many countries, financial transactions taxes have been enormously successful, as explained below. In no country has the tax inflicted any significant damage on the economy: the opposite, in fact. And they are immensely popular. In Britain, for instance, over a million people signed the “Robin Hood Tax” petition for a far broader FTT covering derivatives and other instruments.

The scope for such a tax to curb risky finance is immense. Globally the volume of outstanding derivatives contracts alone is now estimated to be equivalent to $640 trillion dollars – nearly 10 years of annual world economic output – and the sheer excess volume of financial transactions is a threat to global, national and local financial stability. This has to be reined in – and economists from John Maynard Keynes to James Tobin to Joseph Stiglitz have advocated the FTT as a great way to do it, “throwing sand in the wheels” of excessive and risky speculative global finance.

Busting the Wall Street myths

The threats and arguments from Wall Street and the European banking sector are versions of the same threats and spurious arguments we have seen, time and again, around the world, whenever anyone wants to tax financial capital. They are as wrong now as they always are – and it is worth taking the threats apart, point by point.

Claim 1: that this is a ‘tax on working families’ The idea here is that financial institutions will simply pass the cost of the tax onto end investors – such as pension funds.

The exact opposite is true, for several reasons. First, we must distinguish between investors holding shares for the long-term – like pension funds – and high-frequency traders. The former has legitimate needs, while the latter provides no useful service to the economy: their business is to use super-fast computers to flip shares milliseconds ahead of their competitors, to gain a trading edge over their counterparties, which include pension funds. This is pure wealth extraction from others. The 0.1 percent average STT hardly touches the ‘good’ investors, because it is levied only once per trade – while it would hammer the HFT predators (which are effectively levying a private tax on all share owners every time they use their supercomputers to trade against them.)

Second, our further calculations suggest that the cost of the FTT to the $103bn New York State Teachers retirement pension fund, for example, would be just over $20m a year. That may seem like a lot, but compare it to the shocking $330 million in annual management, advisory and legal fees the fund paid to Wall Street (see p94 here), just on the $54 billion of their assets that are externally managed. Add internal administrative costs for the internally managed assets, much of which also flow ultimately to Wall Street, and the total rises to $401 million. Put another way, the STT would cost the fund 1.8 basis points, while the fees cost it 60 basis points. Adding in the New York State and Local Retirement System pension fund, including police and civil service, we calculate a total of $1.33 billion in overall fees and administrative expenses.

These fees are splashed out to 37 different investment advisers (p96 here), and the assets are fire-hosed out into 414 different Wall Street funds (pp 97-100), many of which extract hidden fees not recorded above. That is a lobbyists’ gravy train – and a vastly bigger tax on working families than any STT could ever be. It is also an example of “pension fund capture” – which may help explain why it has been so hard to get many employee pension funds on board with such an employee-friendly tax.

What is more, a STT encourages pension funds to invest as they should: for the long term, rather than speculating with pensioners’ money. Meanwhile, those clever Wall Street investment managers have overseen a $2.5bn decline in those pension fund assets since 2018, while stock markets have soared.

This general principle also applies to any taxes that effectively target the owners of capital (as opposed to targeting workers or employees, say). Such taxes disproportionately strike capital-intensive, low-employment (and often predatory) activities, while hardly touching the patient productive investors employing locals. That is largely because taxes that apply to firms employing large numbers of people are usually a tiny proportion of overall outgoings (whereas things that those taxes help pay for, such as infrastructure or an educated workforce, loom far larger.) Meanwhile, taxes on capital loom far larger in capital-intensive industries employing few people, such as hedge funds. What is more, it is easy to design safeguards to minimise impacts on healthy investing.

Also, over 80 percent of quoted U.S. shares are ultimately owned by the wealthiest 10 percent of Americans, so any residual direct costs on share owners (like pension funds) are shouldered overwhelmingly by richer folk in any case. When the racial or gender dimensions are considered, the picture is even starker. And for the FTT, the wealth impact is even more concentrated than this, because the main beneficiaries of strategies by hedge funds that engage in HFT – the ones targeted by the STT – are billionaires and other high net worth individuals.

Claim 2: Other countries that imposed an FTT regretted it. Sweden is routinely cited here, when an FTT imposed in 1984 led to a reduction in Swedish trading volumes.

The exact opposite is true. Sweden did lose some trading volumes after the FTT was implemented – but this was because of its design flaws. As the IMF reported in 2011, the FTT was only imposed on trades via Swedish brokers, so “it was easily avoided by using non-Swedish brokers.”

By contrast, Britain’s Stamp Duty on securities, a narrow FTT on share transfers is extremely hard to avoid.[1] It raised around £3.5 billion (US$ 4.9 billion) in 2020, equivalent to the salaries of 110,000 nurses, for instance, or seven times the operating budget of Oxford University. This tax, which was introduced in 1694 (that is not a misprint) has not prevented London from being one of the world’s two biggest financial centres, alongside New York. If extended to cover other forms of financial trading, the UK’s FTT could raise multiples of these sums.

The latest EU document notes that in Italy’s and France’s case “the introduction of an FTT did not have a significant impact on market liquidity . . . nor did it have a significant effect on financial volatility” and added that it has “not led to a significant shift towards non-taxable investment vehicles as a strategy for tax avoidance.” And in all these countries, the revenues, added transparency and reduced risky speculation delivered large benefits.

Claim 3: That the financial sector is the goose that lays golden eggs, the “engine” of the economy, thatitshowers tax revenues and jobs on the rest, so we should nurture and protect it.

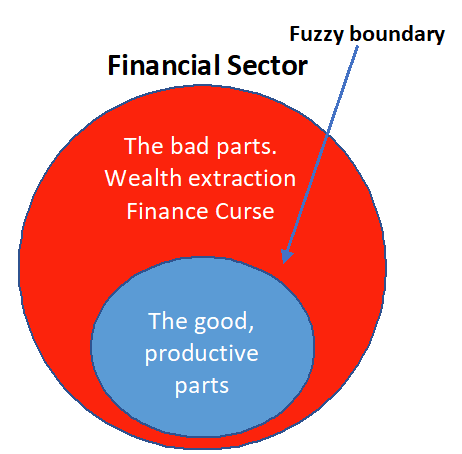

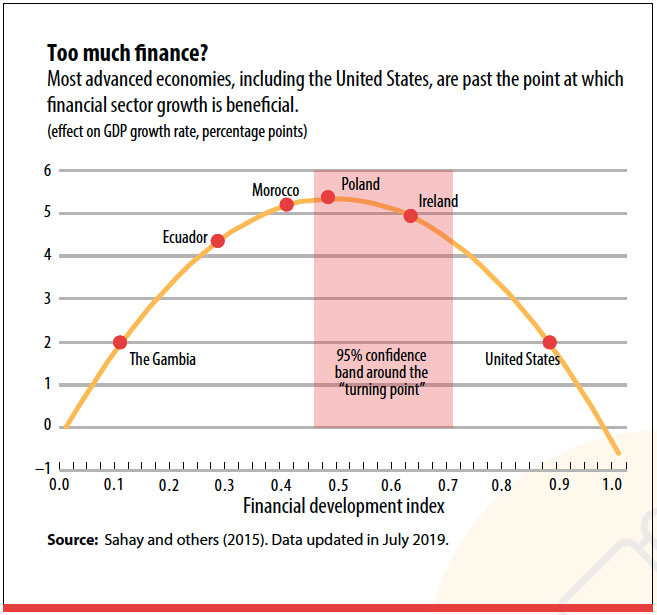

Another complete myth. A financial sector provides some ‘utility’ benefits to any economy, but parts of it also impose severe costs. Two images illustrate this.

The blue section in the image on the left is the ‘utility’ part of finance, providing useful services to the economy: lending to small businesses, providing ATM machines, etc. The red part is the harmful stuff: the hedge fund predation, the high-frequency trading / extraction, and so on. The image on the right, from the IMF, shows there is an optimal size for a financial sector: expansion beyond this tends to harm economic growth in the state that hosts it. The U.S. and U.K. passed this point some time in the 1980s, and both suffer a heavy “finance curse”. Oversized finance is not a golden goose, but a cuckoo in the nest, crowding out and harming other parts of the economy. The conclusion is, “shrink finance, for our prosperity.” Shrink the red part, and keep the blue part. How can we do this? One good way is via an FTT, which kills harmful high frequency trading, but leaves the utility functions unscathed.

Claim 4: that the tax imposes a ‘burden’ on the country or state.

This claim resonates quite widely in the United States, where anti-tax and anti-government ideologies run deep, but it is nonsense. A tax is not a cost to an economy but a transfer within it. An FTT transfers wealth downwards, from wealthy shareholders and owners, many of which are from overseas or out of state, to the local public purse, which deploys resources to fund economy-growing initiatives such as local public infrastructure, courts, or health and education. Studies have suggested that FTTs boost economic growth and net job creation, and reduce the likelihood of financial crises.

An FTT provides additional public benefits, like a tax on tobacco or on gambling, by reducing harmful financial trading and financial risks, as discussed above.

Claim 5: that “all the money will run away” – that our country or state will become “uncompetitive” and the bankers will de-camp or do their trades elsewhere.

They always say that. (Why woudn’t they? Talk is cheap.) When New York’s STT was enacted in 1905, the New York Times thundered that all the money would flee to other stock exchanges like Philadelphia’s or Chicago’s, and New York would be like those “medieval cities, which fell out of the course of modern commerce.” Three months later, the NYT retracted the opinion, admitting it had been a great success. And now consider that immense gravy train of Wall Street fees extracted from New York’s pension funds described above: why on earth would Wall Street run away from that? In fact, of the many US pension fund assets invested overseas, the top destination is the United Kingdom – which has the highest FTT of any major country.

In fact, FTTs of different kinds are happily in place in Belgium, China, Colombia, Cyprus, Egypt, Finland, France, Hong Kong, India, Ireland, Italy, Kenya, Malaysia, Malta, Pakistan, Peru, Philippines, Singapore, South Africa, South Korea, Spain, Switzerland, Taiwan, Tanzania, Thailand, Trinidad & Tobago, Turkey, United Kingdom and Venezuela – and those are just the ones we know about. Denmark and Poland are considering them.

As a detailed IMF study put it, FTTs “do not automatically drive out financial activity to an unacceptable extent,” they are “certainly feasible” even unilaterally, and “would likely be quite progressive.”

Many of of those FTTs were brought in since the last global financial crisis – and precisely none of the FTTs trashed their local financial centres. It is also almost certain, though we haven’t checked every case (here’s some Kenyan FTT lobbying, for instance), that financial interests threatened armageddon ahead of the introduction of every one of them, often brandishing Sweden as if it supported their arguments.

Don’t believe the hype. These ‘competitiveness’ stories are a hoax.

In short, since the first FTT was pioneered in the Netherlands in the 1630s, such measures have always been passed in response to fiscal crises. Pretty much every country and state across the globe faces a fiscal crisis now. The time to get these taxes into the books is today.

Further reading

James S. Henry is an investigative economist and lawyer, Global Justice Fellow at Yale, Board member of Amnesty Internatinoal US, and Senior Advisor to the Tax Justice Network.

John Christensen is an economist and former head of the government economic services of the British Channel Island of Jersey. He chairs the Board of the global Tax Justice Network.

David Hillman campaigned to Ban Landmines and Drop the Debt before helping found the Robin Hood Tax (RHT) campaign to tax the finance sector better, sparking RHT campaigns across Europe and in the US.

Nicholas Shaxson is a financial journalist and author of Treasure Islands, a book about tax havens, and The Finance Curse, about the perils of oversized financial sectors. He also writes for the Tax Justice Network.

[1] As the IMF explains: “the U.K. stamp duty is a tax on the registration of shares in U.K. registered companies. Investors purchasing shares in U.K. companies anywhere in the world must pay stamp duty in order to ensure their legal claim on the shares.” Austrian economist Stephan Schulmeister has produced a more detailed analysis of the Swedish experience, which he contrasts with a much more effectively designed transaction tax in the United Kingdom: the full report can be accessed here.