Sometimes things move slowly – and then they go very fast indeed.

“[A] consequence of an interconnected world has been a thirty-year race to the bottom on corporate tax rates. Competitiveness is about more than how U.S.-headquartered companies fare against other companies in global merger and acquisition bids. It is about making sure that governments have stable tax systems that raise sufficient revenue to invest in essential public goods and respond to crises, and that all citizens fairly share the burden of financing government. President Biden’s proposals announced last week call for bold domestic action, including to raise the U.S. minimum tax rate, and renewed international engagement, recognizing that it is important to work with other countries to end the pressures of tax competition and corporate tax base erosion. We are working with G20 nations to agree to a global minimum corporate tax rate that can stop the race to the bottom. Together we can use a global minimum tax to make sure the global economy thrives based on a more level playing field in the taxation of multinational corporations, and spurs innovation, growth, and prosperity.”

Remarks by Secretary of the Treasury Janet L. Yellen on International Priorities to The Chicago Council on Global Affairs, April 5, 2021.

If you blinked recently, you might have missed the idea of a global minimum tax rate for multinational companies, as it shifted almost imperceptibly from the wild margins of tax justice, to becoming the settled will of the world’s richest countries. Countries which are also, of course, home to the multinationals responsible for the most aggressive profit shifting and tax abuse…

Tax sovereignty: the narrative shifts

It feels like an age since the Tax Justice Network began calling for an end to the race to the bottom – for multinational companies to face a meaningful rate of corporate tax, regardless of how and where they manage to engineer their profits. And even in 2019, when a global minimum tax was presented as the second pillar of the G20/OECD reform process (which began after the global financial crisis and has still not delivered), progress felt distant at best. When the December 2020 deadline came and went, it started to feel as if the chance might have been wasted.

But in a few months of 2021, the slow shift has become a sudden one. In January, President Biden was sworn in, and a new US administration began to appoint some of the country’s best tax (justice) experts to the Treasury, starting with Prof. Kim Clausing.

In February, the UN FACTI panel (the High-Level Panel on International Financial Accountability, Transparency and Integrity) presented its final report, calling for sweeping reforms to the global architecture around tax and illicit finance – including a global corporate minimum tax rate.

Now, US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen has signalled that the US is throwing its full weight behind a global minimum corporate tax rate – and framing this quite explicitly as an end to the race to the bottom.

This is a powerful narrative shift, in favour of tax justice. Once, the defenders of the race to the bottom wrapped themselves – unchallenged – in the mantle of “tax sovereignty”. Every state must have the freedom, they opined, to set the tax rules and rates they wished – regardless of the damage it might do to their neighbours. Anything else would be an unconscionable erosion of tax freedom…

Secretary Yellen, holding perhaps the most powerful single role in the global economy, has confirmed the flipping of this malign, hard right trope on its head. Instead, Yellen argues the tax justice case: we need to limit the worst behaviours of states that make up the race to the bottom, precisely so that we can all enjoy tax sovereignty: so that “governments have stable tax systems that raise sufficient revenue to invest in essential public goods and respond to crises… [and t]ogether we can use a global minimum tax to make sure the global economy thrives based on a more level playing field in the taxation of multinational corporations, and spurs innovation, growth, and prosperity.”

Without a degree of international cooperation and coordination, individual states lack the ability to tax wealth and income, including corporate profit, that can be hidden offshore. That leaves inequalities needlessly high, and uncounted, and inhibits inclusive public policy.

The tax freedom that matters is the freedom of people to choose governments that can deliver the level of revenues, progressively raised and spent, that meets their preferences – instead of being limited to governments that cannot tackle inequalities or deliver sustainable public finances, due to the undermining actions of tax havens.

A global minimum corporate tax rate is not sufficient alone to ensure this; but it is a significant step on the road. The narrative shift, to recognise that all of our tax sovereignty depends on constraining the most damaging effects of tax havenry, is powerful.

OECD obstacles

Things are never, of course, as easy to deliver as they are to wish for. And there are major challenges for a global corporate minimum tax rate, even with full US support.

There remain significant difficulties in the OECD process, with its two-pillar proposals. First, there is no common ground on ‘Pillar One’. This is the element which would go beyond the archaic arm’s length principle and introduce some element of formulary apportionment (that is, allocating a share of each multinational’s global profits to the places where they actually do business, in the form of sales and employment). The US (under Biden, as under Trump) wants Pillar One to apply to all businesses; the EU is focused on the big tech multinationals; and the OECD proposal to identify ‘consumer-facing’ businesses falls somewhere in between these.

As things stand, the OECD proposal is highly complex and would retain arm’s length pricing for most profits, and therefore result in relatively little reduction in profit shifting – making it largely unattractive for most countries. At the same time, the proposal would require global treaty change, meaning that it could very easily be blocked – including by the US Congress, regardless of whether the Biden administration had come around to support it.

‘Pillar Two’ contemplates a global minimum corporate tax rate. This has the potential to go a long way to stop profit shifting, not by making it harder to achieve but by making it much less rewarding – since multinationals would, in theory, end up being taxed at the minimum rate even if they managed to shift the profits to a zero rate jurisdiction.

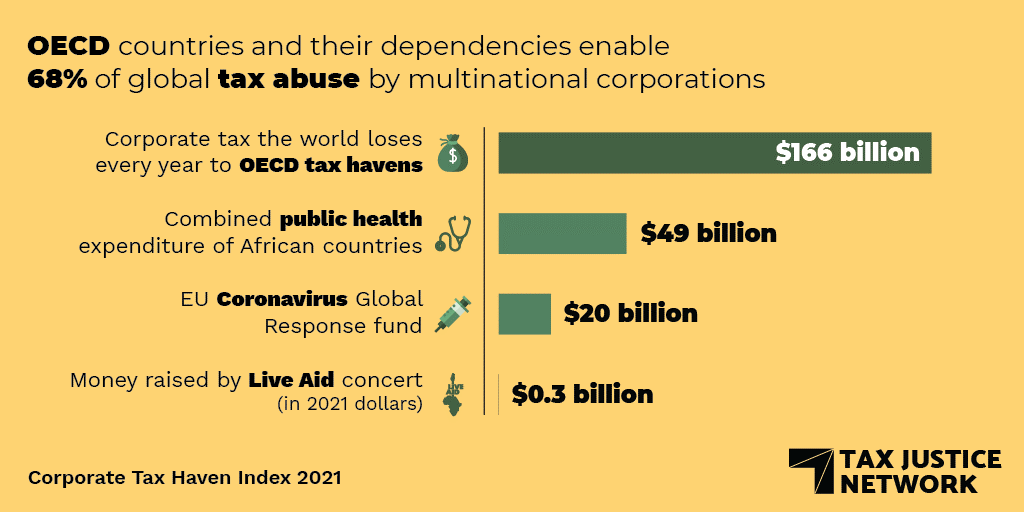

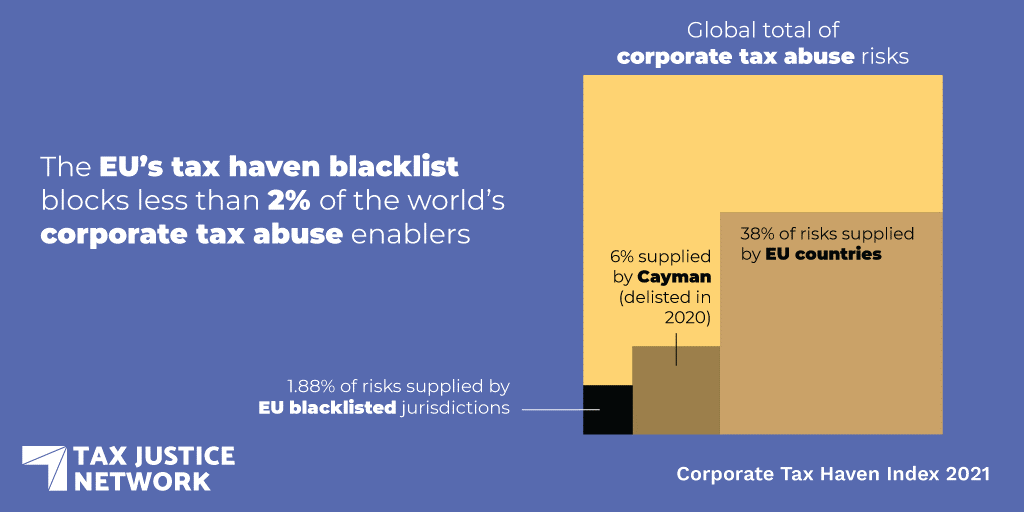

Here again though, the current OECD proposals are highly complex, and have been very unambitious. And an argument about ‘rule order’ – in simple terms, whether the home country of a multinational goes first in levying any top-up tax, or the various host countries – has exposed the major distributional question. Despite some initial optimism, most non-OECD members have by now become thoroughly disillusioned with the process. An outcome that favours OECD members, despite lower-income countries bearing disproportionately high revenue losses due to profit shifting, would be unconscionable – but, sadly, not entirely unexpected.

Lastly, the insistence that the two pillars are inseparable, and must be delivered jointly, creates a hugely complicated contraption requiring great resources to move ahead, but with little certainty over any benefits.

The way forward

Stepping out of the limitations of the OECD process, things very quickly start to look much brighter. This is for three main reasons.

First, the two pillars can be separated – and that means the unworkable and unambitious ‘Pillar One’ can be left behind, along with the requirement for global treaty change. Instead, a global minimum corporate tax can be taken forward by a coalition of the willing. (In fairness to the OECD secretariat, they have raised this possibility at times also, recognising the practical difficulties of their Pillar One.) With the US and Germany (and the European Commission) committed to a minimum tax, broad agreement on the shape could be reached relatively quickly.

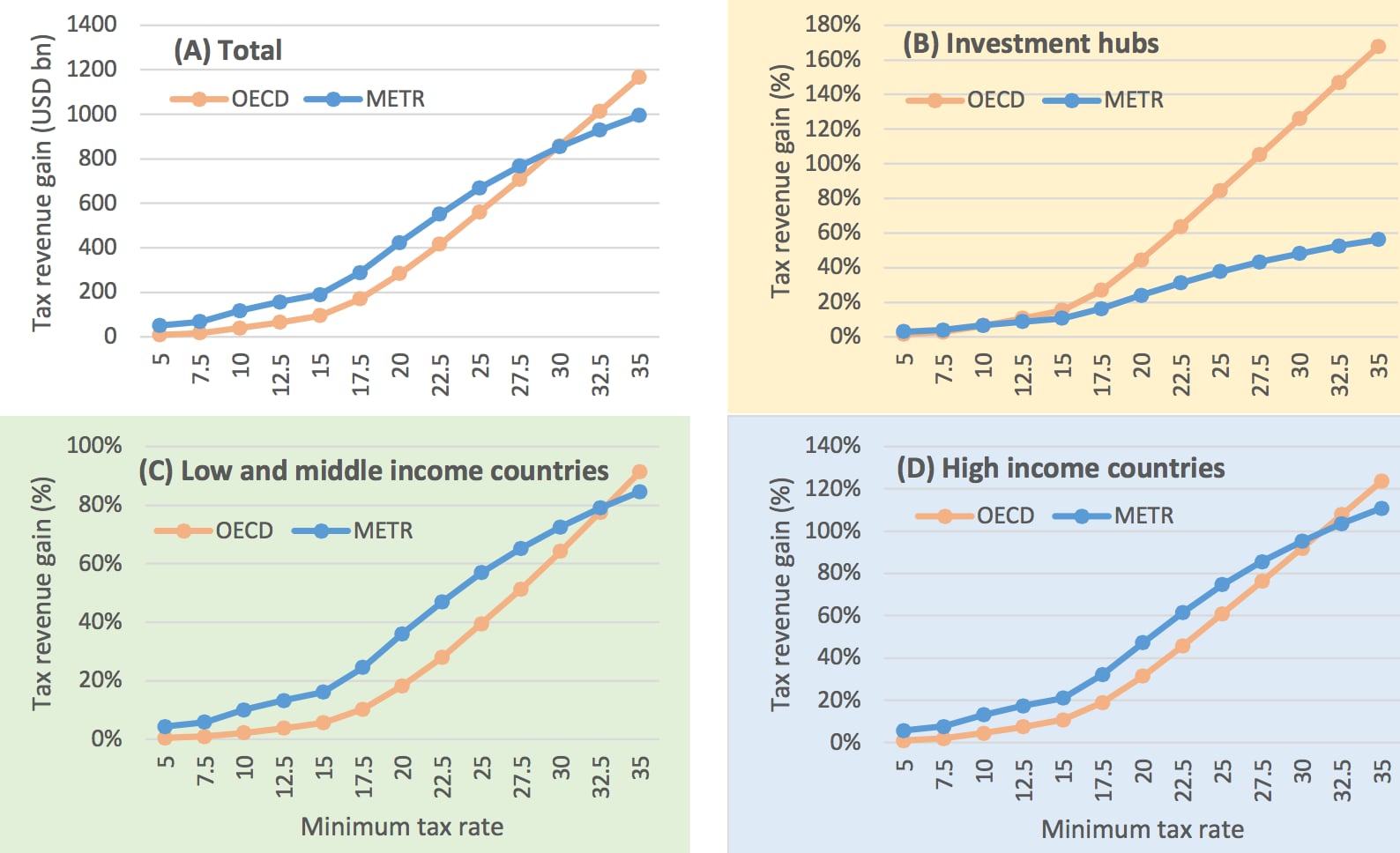

Second, the OECD leadership’s longstanding insistence on a very low minimum rate of 12.5% can be set aside. The Biden administration has indicated a rate of 21%. The Independent Commission for the Reform of International Corporate Taxation has proposed 25% as an absolute minimum; while discussions among various groups of lower-income countries have suggested higher rates still, to ensure that they are not disadvantaged. Negotiating upwards from 21% – and with the possibility of different countries taking their own approaches as appropriate – would provide a quite different dynamic.

And third, the setting aside of Pillar One creates the possibility of pursuing a more ambitious approach to the minimum tax. Our proposal for the METR, or Minimum Effective Tax Rate for multinationals, does just this. We propose a method that builds on the technical efforts of the OECD secretariat, who have done sterling work in establishing various approaches to identify and to apportion taxable profits, but shifts the politics substantially.

In effect, the METR combines the two pillars by identifying under-taxed profits, and then apportioning these for ‘top-up’ taxation on a formulary basis, according to the location of multinationals’ real activity. In this way, the METR cuts through any ‘rule order’ debates and instead treats all countries, home or host, on an equivalent basis.

Our modelling of the METR shows that countries at all income levels may receive substantially higher revenues, with the exception of some of the most egregious profit shifting jurisdictions (which fare better under OECD proposals – and would now not be able to block progress simply by opposing any treaty change).

At the moment, the best guess is probably that the OECD will deliver something in the summer. This will most likely involve a coalition of the willing moving ahead with a minimum tax of some sort, but with the risk of adhering too closely to the Pillar Two proposal and ending up with something of limited effectiveness and high complexity, that may benefit the (OECD) home countries of multinationals rather more than lower-income country hosts of multinationals’ activities. But even in this case the shift, in terms of leading countries committing to end the race to the bottom, will be a powerful one.

Adoption of the METR proposal would raise substantially higher revenues across the board, and in a globally progressive way that would provide an important counter to the still-rising costs of the pandemic.

Politically, the momentum for globally inclusive solutions at the UN, rather than the rich countries’ club at the OECD, will continue to grow – and especially if a one-sided minimum tax solution emerges from the OECD now. The FACTI panel report called for the negotiation of a UN tax convention, which would provide the basis for an intergovernmental body under UN auspices to set corporate tax rules in future – including a global minimum tax rate designed to benefit all.

That the US administration is now leading the push for an ambitious global minimum tax rate confirms this as the new norm. The decisions set to be made in the next couple of months, over technical design and political inclusion, will determine just how effective this can be in bringing an end – finally – to the decades-long race to the bottom in corporate tax.

With the confirmation of this new narrative, it seems likely that what is left undone in the OECD process will be resolved through a combination of unilateral and UN action.