Alex Cobham ■ $300bn in new tax revenues? Weighing the US intervention in global tax reform

The Biden administration has continued its charge to drive through international corporate tax reforms. Yesterday we evaluated Treasury Secretary Yellen’s call for an end to the race to the bottom. At the same time, the Biden administration released its ‘Made in America tax plan’, and the headlines of its international proposals were more or less simultaneously leaked from the OECD where they had been presented.

So today, we’re trying to read the runes. First, what’s the broad significance of the Biden tax stance? Second, what specifically is achievable within the last couple of months of the G20/OECD reform process – and how much tax revenue is at stake now, and for who? And third, due to how much will be left still to do in any scenario, what’s the global outlook after that?

1. The ‘Made in America tax plan’

The Biden administration’s ‘Made in America tax plan‘ is an impressive piece of work. For one thing, as a political statement on tax it’s the most academically impressive document I can remember seeing. Unsurprising, perhaps, given the quality of the academic staff that the US Treasury has taken on, but great to see all the same.

More substantively, this is a statement of powerful intent. The plan identifies a series of major problems with the US tax system, and lays out targeted actions to address each of them. This sits within an overall framing which is itself an impressive reframing of what has been an ideologically skewed debate in the US for so long.

The ‘Made in America tax plan’ is nothing short of the reclaiming of a tax justice narrative for US corporate tax policy.

The approach is based on six aims or principles, each of which is supported by an array of evidence and gives rise to specific measures:

- Revenue. US revenue from corporate income tax halved due to the Trump reforms, from 2% of GDP to just 1%, which in any case compares poorly to an OECD average of around 3%. Proposed: The US CIT rate will be raised to 28%.

- Fairness. The share of labour in US income has been declining for years, but the share of labour in US federal tax revenues has been trending upwards – from around a 50% share in 1950, to an 80% share by 1980; followed by some ups and down but most recently rising since the early 2010s to above 85%. Proposed: The administration will invest substantially in reversing the loss of tax enforcement capacity.

- Reduce profit shifting. “[T]he United States has an ‘America last’ approach to corporate taxation, incentivizing shifting profits to high-tax and low-tax jurisdictions alike…. the current GILTI regime maintains profit shifting incentives… Since taxes paid in high-tax jurisdictions can generate tax credits that allow for untaxed profit shifting into tax havens, companies can blend the two streams of income and achieve a tax burden that is only about half that of domestic companies.” Proposed: The global minimum tax for US multinationals will be significantly strengthened.

- End the global race to the bottom. ‘The average statutory corporate rate among OECD countries was 32.2 percent in 2000; by 2020 this had fallen to 23.3 percent. Widening the time horizon shows that the fall has been even more precipitous; in 1980, OECD statutory corporate rates were rarely less than 45 percent.” Proposed: The administration will “reduce incentives for foreign jurisdictions to maintain ultra-low corporate tax rates by encouraging global adoption of robust minimum taxes.“

- Make large, profitable companies pay their fair share. A targeted measure to end the abuses of those companies that declare large profits to shareholders, but little or no taxable income to the authorities. Proposed: The administration will enact a 15% minimum tax on book income.

- Moving towards a resilient and sustainable economy. Proposed: Rather than providing subsidies to dirty fossil fuel energy or easily abused incentives to intangible property, the administration will switch to clean energy subsidies and incentives for (genuine) R&D.

The ‘Made in America tax plan’ is nothing short of the reclaiming of a tax justice narrative for US corporate tax policy. And because corporate tax is a key underpinning of a broader progressive tax system, including as a form of wealth taxation, this is a major contribution to tax justice overall in the US.

2. Economic assessment: $300bn or more, globally

Central to the ‘Made in America’ plan is the piece about changing the incentives for other jurisdictions, by encouraging a robust, global minimum corporate tax plan. As laid out here yesterday, the US position has added real ambition to the OECD reforms which have been in grave danger of fizzling out into nothing.

While the global minimum tax rate is ‘pillar 2’ of the OECD process, we now have via the FT a leak of the US position on ‘pillar 1’. Pillar 1 is a move to tax some profits on a formulary basis, instead of the arm’s length principle which is no longer fit for purpose. This is an attempt from the US to revive it.

The OECD secretariat, and France in particular among member countries, have insisted on the complete package: that the pillars be inseparable. But this threatens any progress at all, for two main reasons.

First, pillar one as proposed would require global treaty change. That means that it could easily be blocked by those havens that would lose most, like Ireland and the Netherlands. If pillars are required to be jointly introduced, the block to pillar one is a block to both.

And second, there is no agreement on pillar one. Even with the Biden administration signalling early that they’d take the Trump opt-out (mislabelled as a ‘safe harbor’) off the table, the differences remain great. The EU countries and some others have largely sought a pillar one that addresses ‘digital’ multinationals only. The US (all administrations) wanted it to apply to all sectors, so their tech companies are not singled out.

The latest OECD proposal tries to split the difference, with a scope of ‘consumer-facing’ businesses – roughly 2,300 multinationals, they reckon. Now the US is offering something to try to get this moving – but it is much narrower than anything anyone has proposed. Per the FT, the US proposal covers “only the very largest and most profitable companies, regardless of sector, based on level of revenue and profit margins…[and] would likely include about 100 companies, comprising the big US tech groups as well as other very large multinationals.”

The proposal looks real, in the sense that it would involve a genuine formulary approach (which is the end game for all international corporate tax). The very important downside, in addition to narrowing the scope so dramatically, is that it would apportion taxable revenues only on the basis of sales, an unbalanced formula that would fail entirely to recognise employment as a factor of production, and so would privilege large (rich) market economies over lower-income producer countries.

The proposal is potentially face-saving, in the sense that it offers France and the OECD secretariat something, instead of having to accept that there be no pillar one at all. This is consistent with the US aim of having pillar two broadly accepted.

As ever with OECD processes, the entire thing leaves the citizens and non-corporate taxpayers of the world in the dark. (An important reason for the move to a UN setting, which looks increasingly likely – as with the UNFCCC on climate change, for example, this would ensure the ability of the world’s people to scrutinise the negotiating positions of their own governments.) One thing we really need to know is whether the Biden proposal would still require global treaty change.

If it does, then it’s hard to see the result going through the US Congress, never mind a series of tax havens signing up. In this scenario, the proposal starts to look like a pure face-saving olive branch, as it won’t ever happen – but would still allow pillar two to move ahead alone, in a coalition of the willing.

It’s possible though that elements of our METR proposal (a Minimum Effective Tax Rate) have been included. In this, we combine the best technical elements of pillar one into a global minimum tax to deliver pillar two, and without requiring treaty changes. The US proposal might just manage that if a similar line on the key point was taken. And then it could fly.

The OECD approach, with a Biden-backed minimum rate of 21%, would yield some $300bn or more in additional revenues worldwide – delivering a large part of of Janet Yellen’s call to end, finally, the race to the bottom.

But even if that’s the case, this will remain relatively small beer compared to the prize of a genuinely effective global minimum tax rate. The pillar one discussions may still turn out to be important, because of the norm-setting effect of agreeing to tax even this handful of large multinationals on the basis of unitary taxation and formulary apportionment – just as the G24 group of countries had initially proposed, and the Inclusive Framework supported, before the OECD eliminated it in order to focus on the Trump-France bilateral deal.

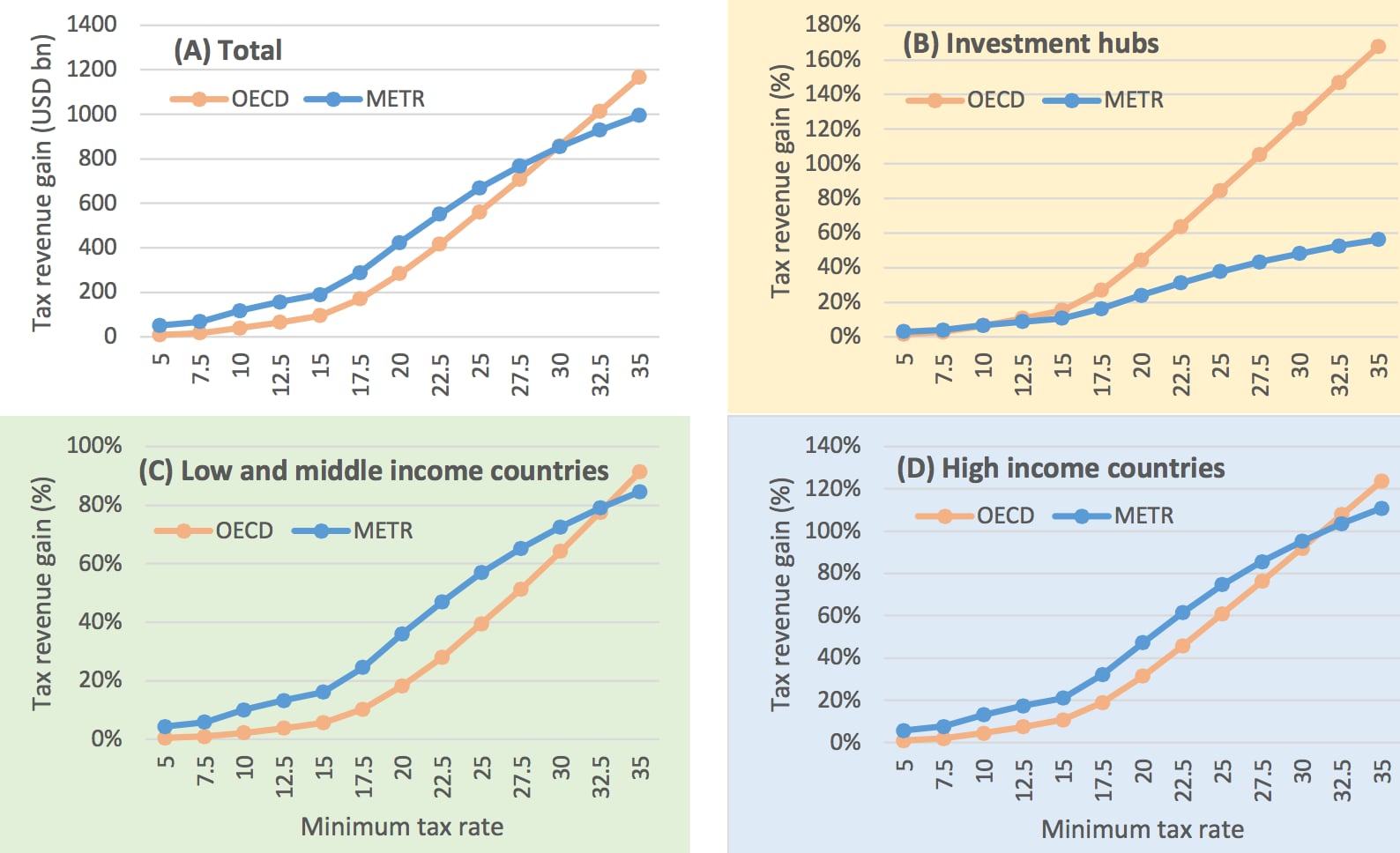

In terms of the revenue gains to be had from any feasible outcome of the OECD process, however, the importance of an ambitious global minimum corporate tax rate is clear – and hence the Biden administration’s focus is well supported.

Our modelling of the OECD pillar 2 proposal, in order to compare with our METR (Minimum Effective Tax Rate) proposal, suggests that even the OECD approach, with a Biden-backed minimum rate of 21%, would yield some $300bn or more in additional revenues worldwide. That would include increases in corporate income tax revenue for high income countries of 30% or more on average, and for low and middle income countries of 20% or more. While the OECD approach is somewhat globally regressive compared to the METR, it would still generate substantial gains for most countries, by disciplining profit shifting worldwide – delivering a large part of US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen’s call to end, finally, the race to the bottom.

3. Global outlook

The chances of a deal in the OECD process by June – in time for the July meeting of G20 finance ministers – are now sharply higher than they were, even last week. The chances of that deal having a meaningful impact on the scale of global profit shifting are also much higher.

The Biden administration is leading the charge for a new politics of tax justice, which will not only yield benefits for people in the US, but, due to their hegemonic power, has the possibility also to spread wider. Just as Trump’s attitude to truth and tax seemed to empower a generation of politicians around the world to act in his image, so – we might hope – a US administration leading on tax justice may also shift norms and narratives.

But even a good outcome should not blind anyone to the irretrievable, unacceptable flaws of the underlying process. The structural injustice of international tax rules being set by a club of rich countries, cannot provide the basis for addressing the inequalities in global taxing rights.

The need for a UN tax convention, setting the basis for a globally inclusive, intergovernmental body to negotiate tax rules under UN auspices rather than the rich countries’ club at the OECD, will remain clear and urgent.

Related articles

The elephant in the room of business & human rights

UN submission: Tax justice and the financing of children’s right to education

14 July 2025

How the UN Model Tax Treaty shapes the UN Tax Convention behind the scenes

The 2025 update of the UN Model Tax Convention

9 July 2025

One-page policy briefs: ABC policy reforms and human rights in the UN tax convention

Bad Medicine: A Clear Prescription = tax transparency

Tax justice pays dividends – fair corporate taxation grows jobs, shrinks inequality

Reclaiming tax sovereignty to transform global climate finance

The millionaire exodus myth

10 June 2025