This blog is an expanded version of a blog published originally on CIATblog, with kind permission.

Today, the Tax Justice Network publishes its new study on “Vulnerability and exposure to illicit financial flows risk in Latin America.” It is the most comprehensive and systematic analysis of illicit financial flows risks in Latin America to date, and provides the basis for granular policy decisions. Illicit financial flows (IFFs) are transfers of money from one country to another that are forbidden by law, rules or custom. They encompass flows from both illegal origin capital (classic money laundering, arms, drugs, human trafficking, corruption) and legal origin capital (tax evasion and avoidance).

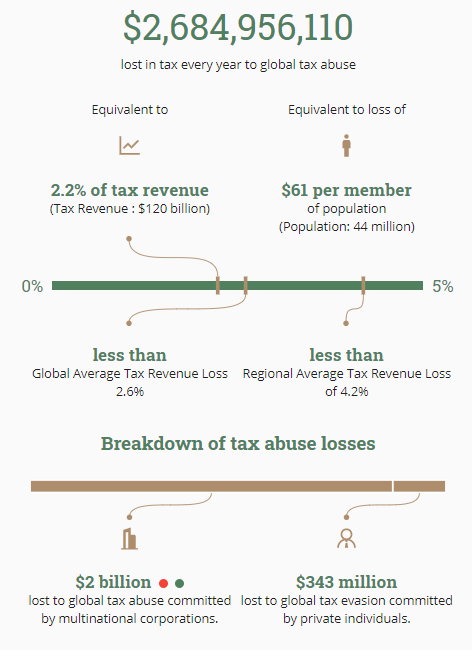

Illicit financial flows affect the economies, societies, public finances and governance of Latin American countries – as they do in all other countries. Latin American and Caribbean countries account for a significant share of trade-based illicit financial flows, and are estimated to lose US $43bn annually to global cross-border tax abuse. The urgent need to tackle illicit financial flows is clear. Despite global agreement in target 16.4 of the UN Sustainable Development Goals, however, the international architecture remains entirely insufficient to support progress – although the UN FACTI panel’s final report, due in February, will identify key gaps and make recommendations for immediate action.

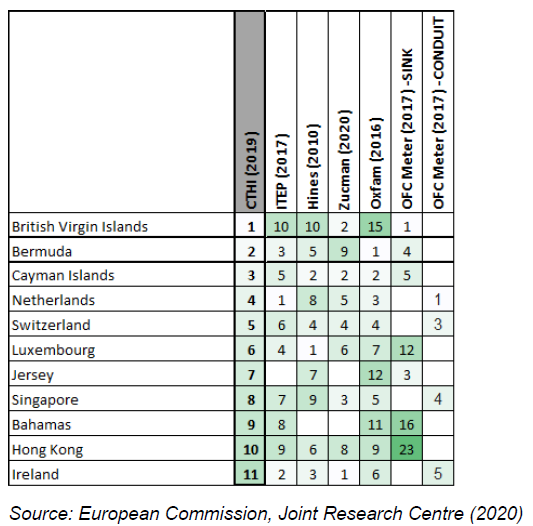

At the national level, a particular challenge in countering illicit financial flows lies in prioritising among the many channels; and within each channel, identifying the economic partner jurisdictions responsible for the vulnerability. We address this research gap by elaborating on an approach pioneered in the report published by the High-Level Panel on Illicit Financial Flows from Africa (“Mbeki Panel”), which can be used to generate proxies for illicit financial flows risk by combining bilateral data on trade, investment, and banking stocks and flows, with measures of financial secrecy in partner jurisdictions. This approach rests on the observation that illicit financial flows are hidden; thus, the likelihood of an illicit component increases with the level of secrecy of any given transaction. Trade with companies in Cayman Islands will be more risky than trade with companies in Ecuador. The analysis also points to geopolitical implications, and below we explore questions of OECD responsibility for threats faced in the region.

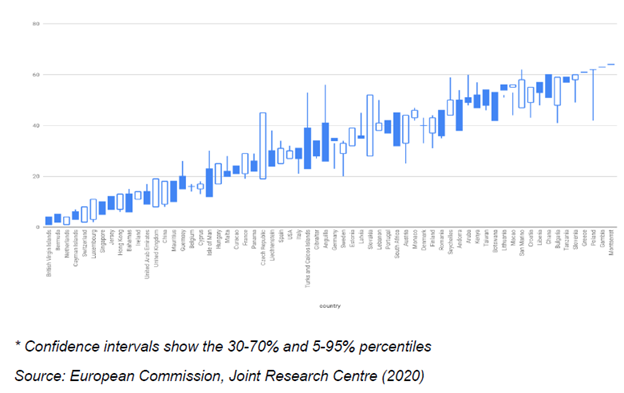

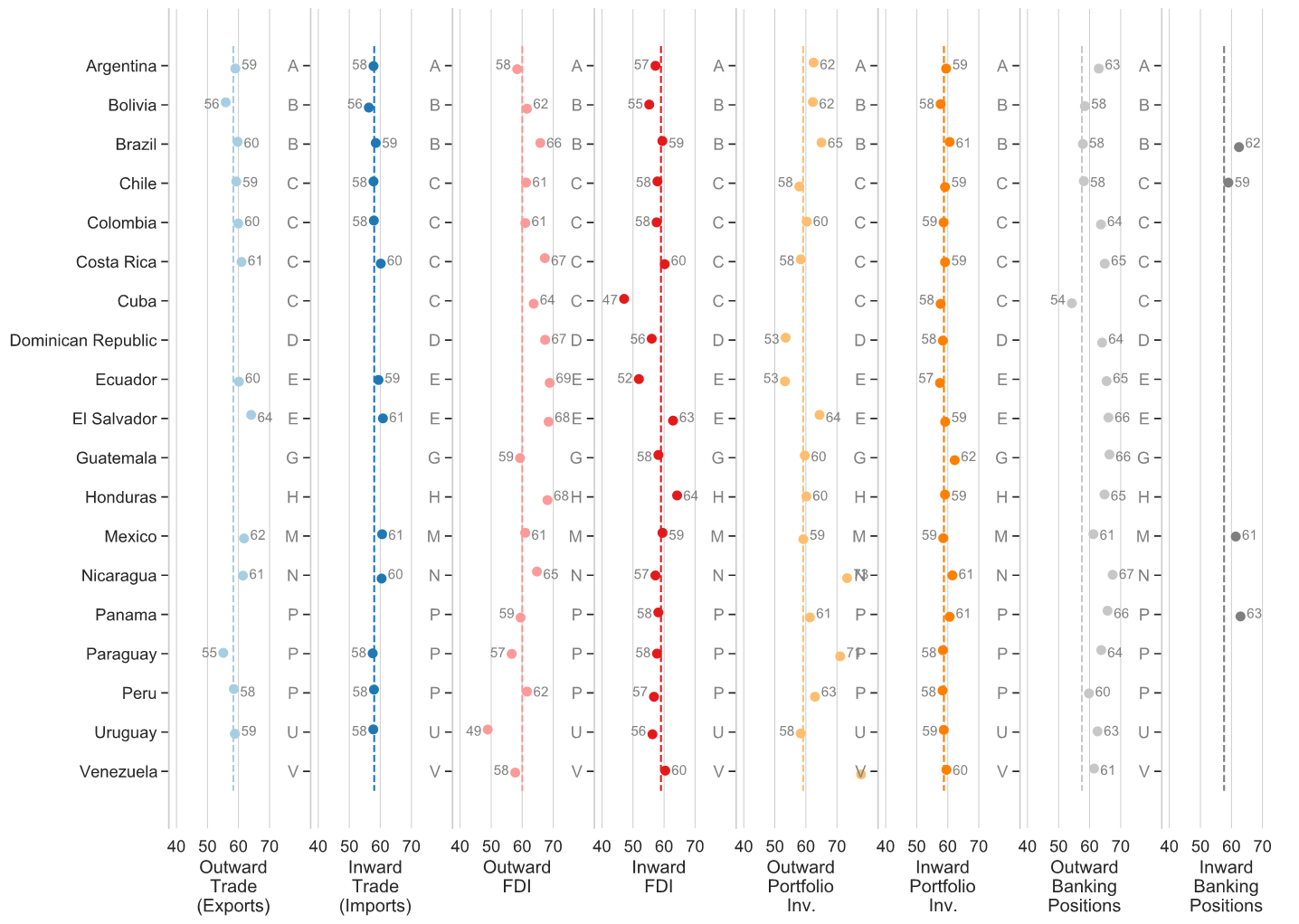

Chart 1 below illustrates the vulnerability in the eight economic channels for the 19 countries in Latin America under review, where zero represents no vulnerability or secrecy in the economic channel, and 100 implies highest vulnerability, or economic flows with an entirely secretive counterparty. The dotted lines represent the global average of vulnerability, so it can be seen that Chile, for example, faces roughly the average risk in most channels, while Mexico is more vulnerable in most.

Chart 1: Latin American jurisdictions’ vulnerability to illicit financial flows in different channels, 2018. Dotted lines represents the global average.

Risks associated with Foreign Direct Investment

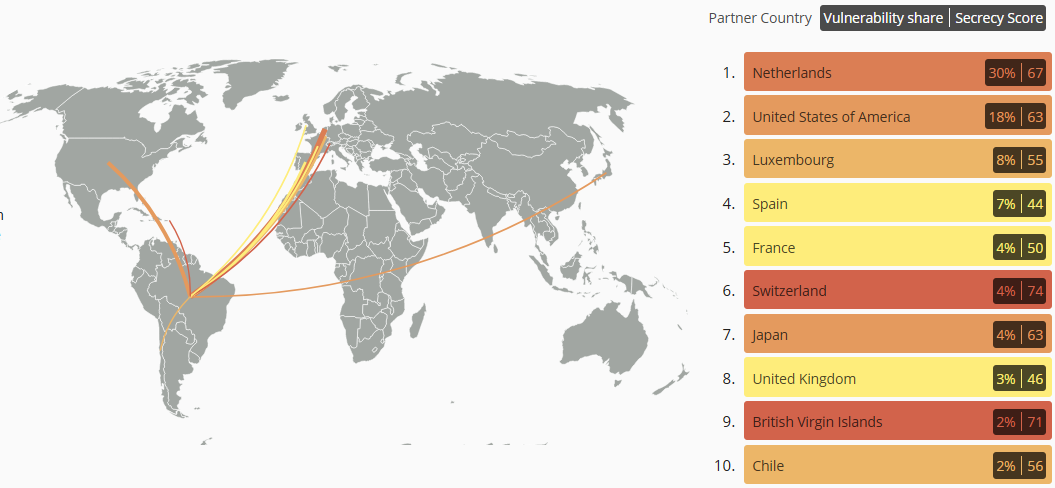

The study discusses how the data-driven vulnerability profiles for individual Latin American countries relate to, and can be used to help identify, real cases of tax avoidance, evasion, money laundering and corruption. For instance, the risks stemming from inward FDI for tax avoidance by multinational companies can be illustrated with the case of Coca-Cola in Brazil. According to a media investigation published in 2018, Coca-Cola Brazil was involved in a tax avoidance scheme. At the core of the allegations is an investment from two companies registered in the U.S. state of Delaware, a corporate tax haven and secrecy jurisdiction, into a subsidiary in Brazil. Chart 2 shows the vulnerability of Brazil’s inward foreign direct investment 2018.

Chart 2: Vulnerability of Brazil’s inward foreign direct investment stock in 2018. Source: IFF vulnerability tracker.

The Netherlands is responsible for 31 per cent of all Brazilian vulnerability in inward foreign direct investment (Chart 2). Brazil and the Netherlands have a tax treaty which can be exploited by multinational corporations. Due to its position as a corporate tax haven and a secretive jurisdiction, Brazilian authorities should pay special attention to Dutch inward investment and analyse the costs, risks, and benefits of the tax treaty between the two countries to consider cancellation of the treaty. Brazil also receives high inward direct investment from other corporate tax havens: are Luxembourg (#6 on Corporate Tax Haven Index 2019), Switzerland (#5), and the British Virgin Islands (#1), and the US (#25), as illustrated in the case of the Brazilian Coca-Cola subsidiary.

In outward direct investment, there is also the risk that domestic companies and individuals make false statements about the relationship, owners, and accounts of their foreign businesses or activities in tax returns. This may be done for round-tripping purposes. That is, to nominally invest abroad with the ultimate destination being the domestic economy, to exploit tax treaties or other provisions only available to foreign investors, or to pay kickbacks for securing contracts abroad. For instance, in 2019, Joaquín Guzmán Loera (a.k.a. “El Chapo”) was found guilty by a District Court in Brooklyn, United States, of drug trafficking and money laundering. According to the United States Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), one of the methods used by El Chapo for laundering billions of U.S. dollars of drug proceeds consisted of using U.S. based insurance companies and controlling numerous shell companies. These shell companies and U.S. based insurance companies, into which El Chapo invested, would be recorded as (derived) outward FDI from Mexico.

Chile offers a striking example of highly concentrated illicit financial flows risks in derived outward foreign direct investment positions in Latin America. Panama dominates (over 17 per cent) all Chile’s vulnerability in outward FDI with over US$15bn of investment. While some of these investments may consist of genuine, tangible real investment interests of Chilean based companies, the magnitudes involved and the secrecy levels found in Panama suggest a significant risk that some of it is there for opacity’s sake. The British Virgin Islands (71) and Cayman Islands (76) are other high secrecy jurisdictions in Chile’s vulnerability in outward foreign direct investment.

Chart 3: Vulnerability of Chile’s outward direct investment (derived) stock in 2018

| Rank | Jurisdiction | Secrecy score | Vulnerability score | Direct Investment Outward (derived) (billions) (USD) | Share of Direct Investment Outward (derived) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Panama | 72 | 17.16% | 15.1 | 14.62% |

| 2 | United States | 63 | 12.47% | 12.5 | 12.14% |

| 3 | Brazil | 52 | 10.64% | 13.0 | 12.61% |

| 4 | Peru | 57 | 10.5% | 11.6 | 11.28% |

| 5 | British Virgin Islands | 71 | 9.93% | 8.8 | 8.53% |

| 6 | Argentina | 55 | 7.65% | 8.8 | 8.52% |

| 7 | Colombia | 56 | 5.59% | 6.2 | 6.06% |

| 8 | Cayman Islands | 76 | 4.74% | 3.9 | 3.81% |

| 9 | Luxembourg | 55 | 3.42% | 3.9 | 3.78% |

| 10 | Uruguay | 57 | 2.98% | 3.3 | 3.20% |

Overall vulnerability of investment outward (derived): 61

While this macro-level analysis signals red flags for the Chilean tax administration, which might consider investigating the outward foreign direct investment stock into some of the highly secretive and more notorious corporate tax havens itself, the next level would consist in applying the same analysis to micro-level outward foreign direct investment and intra-group trade transactions. By applying this vulnerability analysis to transaction level data, administrations can sift through large volumes of data and implement a high level advanced analytics risk mining of their datasets. This model could be applied for example to controlled transactions in transfer pricing returns filed by multinational companies, to customs declaration forms, to suspicious transaction reports, or to SWIFT money transfers, etc. By focusing limited audit capacity on transactions with the highest composite secrecy risks and with the greatest financial values cloaked in secrecy, both the revenue yield and the compliance impact of audits could be greatly enhanced. The Tax Justice Network currently partners with tax administrations to pioneer and evaluate the effects of this approach, and is working towards expanding this approach.

Geopolitical Implications

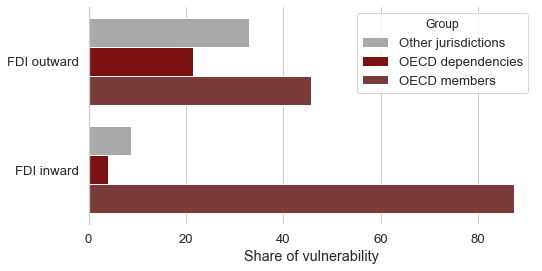

Another important finding of the study concerns the responsibility of OECD member states and their dependencies in the vulnerability (not only) of foreign direct investment in Latin America (see chart 4). In 2018, 91 per cent of Latin America’s vulnerability risk in direct (inward) foreign investment stemmed from OECD countries and their dependencies. The implied political economy of international tax governance points to the need for vigilance in the current “BEPS 2.0” process negotiations around reform of the taxation of multinational companies under the inclusive framework of the OECD. More ambitious proposals for comprehensive reforms, such as those made by the Intergovernmental Group of Twenty-Four (G24) and by the Independent Commission for the Reform of International Corporate Taxation (ICRICT), have been sidelined, as has become evident in the blueprints published in October 2020 by the OECD. Latin American countries should carefully evaluate their political representation at the OECD and the inclusive framework, and assess the potential for an enhanced role through a UN tax body and convention, not least through the FACTI panel.

Chart 4: Vulnerability in direct investment (inward and outward (derived)) 2018 – Top suppliers of secrecy risks faced by Latin America, by OECD membership and dependencies

Offshore tax evasion and automatic exchange of information

An even higher concentration of risks in OECD member states can be found in the outward banking deposits of Latin America. The case of Colombia – one of the Latin American countries which is most actively engaged in the automatic exchange of information system – illustrates the importance of risks stemming from banking relationships. As chart 5 illustrates (last column), the United States remains by far the biggest obstacle to a level playing field for countering banking secrecy by not participating in the Common Reporting Standard (CRS).

Chart 5: Vulnerability of Colombia’s banking claims (derived) in 2018, and AEOI: Automatic Exchange of Information (Y = indicating activated relationship under the Common Reporting Standard; N = absence thereof)

| Rank | Jurisdiction | Secrecy score | Vulnerability score | Value of Banking Claims (derived) (billions) (USD | Share of Banking Claims (derived) | Activated AEOI Relationship? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | United States | 63 | 58.68% | 9.5 | 59.39% | N |

| 2 | Panama | 72 | 28.81% | 4.1 | 25.52% | Y |

| 3 | Switzerland | 74 | 3.22% | 0.4 | 2.77% | Y |

| 4 | United Kingdom | 46 | 2.76% | 0.6 | 3.80% | Y |

| 5 | Spain | 44 | 2.21% | 0.5 | 3.20% | Y |

| 6 | France | 50 | 1.35% | 0.3 | 1.72% | Y |

| 7 | Australia | 50 | 0.94% | 0.2 | 1.20% | Y |

| 8 | Germany | 52 | 0.59% | 0.1 | 0.73% | Y |

| 9 | Luxembourg | 55 | 0.33% | 0.06 | 0.38% | Y |

| 10 | Austria | 56 | 0.28% | 0.05 | 0.32% | Y |

Overall vulnerability of derived banking claims: 61

Latin American countries already participating in the exchange system (i.e. Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Mexico, Panama and Uruguay) might consider working towards a joint position for tweaking the parameters of the system to their needs. For example, requiring public statistics could be an effective means to increase compliance of reporting obligations in major OECD controlled financial centres. In addition, the artificial legal constraints the OECD places on the use of data for criminal corruption and money laundering investigations could be revisited. The Punta del Este declaration, “a call to strengthen action against tax evasion and corruption”, signed by participating ministers from Latin America in 2018, could provide a useful starting point for international political coordination towards more efficient and ambitious data usage. Furthermore, options to achieve fully reciprocal information exchanges, including with the United States, should be explored, including a continent-wide withholding tax on non-participating financial institutions.

All data underlying the report is available freely in the Tax Justice Network’s Illicit Financial Flows Vulnerability Tracker. In February 2021 the website will be updated, providing increased granularity (e.g. vulnerability through agricultural exports) and a user-friendly data explorer.

Policy recommendations

The report offers three broad policy recommendations to counter IFFs more effectively. In each of the chapters, more granular policy recommendations are provided.

1. Enhance data availability

Broadening the availability of statistical data on bilateral economic relationships is a first step for enabling both in depth and comprehensive analyses and meaningful regulation of economic actors engaged in cross-border transactions. In the process of collecting statistical data according to IMF standards, governments would need to build registration and monitoring capacity that likely helps improve overall economic governance.

2. Consider Latin American coordination on countering illicit financial flows risks

The bulk of illicit financial flows risks at the moment is imported into Latin America from outside the region. This finding could help foster joint negotiation positions among Latin American countries when engaging in multilateral negotiations around trade, investment or tax matters. Despite the lack of political organisation at the regional level, which makes coordination and joint action more difficult to achieve, Latin American countries might consider crafting alternative minimum standards for trade, investment, and financial services in order to safeguard against illicit financial flows emanating from secrecy jurisdictions and corporate tax havens controlled by European and OECD countries. Furthermore, Latin American countries should carefully evaluate their political representation at the OECD and the associated Inclusive Framework, and assess the potential for an enhanced role through a UN tax body and convention.

3. Embed illicit financial flows risk analyses across administrative departments

A holistic approach to countering illicit financial flows requires capacity to identify and target the areas of the highest risks for illicit financial flows. Illicit financial flows risk profiles can assist governments to prioritise the allocation of resources across administration departments and arms of government, including tax authorities and customs, the central bank, audit institutions, financial supervisors, anti-corruption offices, financial intelligence units and the judiciary. Within these departments, the illicit financial flows risk profiles would support the targeting of audits and investigations at an operational level as well as the negotiation of bilateral and multilateral treaties on information exchange at a policymaking level. Whether on tax, data, trade or corruption related matters, capacity building strategies at a continental level should include illicit financial flows risk analysis.