The finance curse

Many people labour under an illusion that the financial centre in their country is the magic goose laying golden eggs, showering investment, jobs and tax revenues on the rest of the country. They worry that progressive policies like wealth taxes or stronger labour laws may redistribute the ‘pie’ more fairly, but at the expense of a smaller pie.

The finance curse shows that the opposite is true: progressive policies will not only redistribute the pie more fairly, but by shrinking the financial sector they will expand the overall pie too. The finance curse identifies an apparent paradox: “too much finance” can make a country poorer.

Consider a financial sector as a fried egg. The yolk in the middle is the useful part, helping citizens save for the future, providing loans to small businesses, and so on. The white of the egg is the harmful part. It might contain, for instance, accountants helping wealthy individuals or large multinationals set up tax haven structures to escape tax, or lawyers helping large companies merge to become dominant monopolists, or bankers engaging in the kind of financial engineering that led to the last global financial crisis.

Whereas tax havens are financial centres that transmit harm outwards, to other countries elsewhere, the finance curse means that an oversized financial centre transmits harm inwards, to the country or state that hosts it.

The basic policy prescription that flows from the finance curse analysis is to shrink the financial sector back down to its useful core, to improve prosperity.

An oversized financial centre delivers a range of harms, some more measurable than others.

A first set of harms is akin to a “resource curse” that afflicts countries whose economies are dominated by minerals like oil. Very high salaries in finance drain talented, educated people out of other economic sectors, out of government and out of civil society, damaging all. They distort the real estate markets, making housing less affordable for the majority. Financial inflows deliver another round of damage by raising general local price levels, making it harder for sectors like industry or agriculture to compete against imports, in a further round of damage. Financial booms and busts, notably with the last global financial crisis, deliver yet more economic damage.

An oversized financial sector delivers a second set of harms as financial actors turn away from supporting economic activities towards more predatory ones. A private equity firm, for instance, buys up a healthy, thriving company, then uses financial engineering to extract maximum wealth from that company’s stakeholders – workers, pensioners, tax authorities, suppliers or customers – obtaining windfall profits in the process, and leaving that company weakened. These predatory activities, from “too big to fail” banking, to excess mergers and acquisitions, to the use of debt and complex corporate structures to maximise returns to the owners of capital while also insulating them from risks, are too numerous to list here.

Oversized finance inflicts a third set of harms by ‘capturing’ policy-making and the public conversation, shifting policies towards favouring the needs of the owners of financial capital at the expense of citizens. Because capital is mobile, they routinely threaten that if they are not given special treatment – whether tax cuts and loopholes, weak antitrust enforcement, or lax financial regulations – they will run away to another financial centre.

These different harms caused by an oversized financial centre have a range of negative effects.

One more measurable effect is on economic growth. An oversized financial centre does not only redistribute the economic “pie” in a regressive direction (ie, the rich get richer, the poor get poorer), but it also shrinks the overall pie.

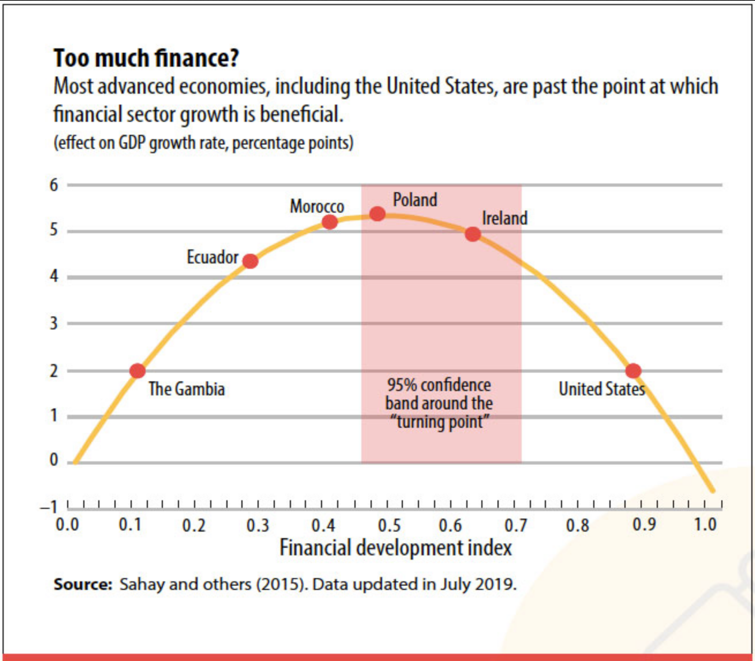

A range of different research papers demonstrate this, finding the same essential trend as financial sectors grow in size. Initially, with no finance, little more than subsistence farming is possible. Then, as finance develops, it helps an economy become more sophisticated, supporting the creation of wealth. The financial sector may then grow to an optimal size, where it is providing all the useful services an economy needs. Beyond this point, however, it starts to harm growth. This graph, from the IMF, illustrates the essential relationship. A number of other studies find the same basic relationship.

Specific country estimates have been made too. One study from Sheffield University estimated that the UK’s oversized financial sector resulted in a £4.5 trillion cumulative loss of growth potential from 1995-2015, compared to the growth potential that would be possible with an optimal (smaller) sized sector. An earlier estimate for the United States found cumulative economic losses of $13-23 trillion from 1990-2023.

Yet the finance curse is a multi-dimensional phenomenon that inflicts damage far beyond economic growth.

For instance, oversized finance boosts inequality, undermines democracy and people’s faith in the rule of law. It damages national security. It corrupts markets, makes businesses more fragile, less resistant to shocks, and harms good governance.

It also has powerful geographical, racial and gender effects, as predatory financial activities extract wealth and talented people from poorer regions, where the victims are disproportionately women, girls, ethnic minorities, and from vulnerable groups requiring a safety net, and delivering it up to a relatively small number of ‘winners’ in the financial centres, who are disproportionately white men.

Ultimately, the finance curse is a liberating analysis. Once people understand that a country’s financial sector is not a magic goose laying golden eggs, but more like a vacuum cleaner hoovering up wealth from other parts of the country, then people will stop worrying that higher corporate taxes or stronger financial regulations or antimonopoly laws will reduce prosperity. The opposite is true: we can have more progressive policies, finance will be smaller, and overall prosperity – not to mention democracy, society, security, and the rule of law – will be recovered.

Further reading:

- “Too much Finance”. A collection of research papers showing the finance curse proposition.

- 20 reasons to shrink your financial centre. A set of different conceptual frames to understand the finance curse.

- The finance curse: how the outsized power of the City of London makes Britain poorer, article in The Guardian laying out the general thesis, from a UK perspective. and linking to Nicholas Shaxson’s book The Finance Curse.

- The UK’s Finance Curse? Costs and Processes. An academic paper estimating the hit to UK growth from oversized finance.

- Overcharged: The High Cost of High Finance, Roosevelt Institute, 2016. Estimating that oversized finance inflicts a $13-22 trillion cost to the U.S. economy from 1990-2023.

- The Finance Curse: Britain and the World Economy, 2016. The first academic paper on the finance curse in a peer-reviewed journal.

- The original finance curse e-book, 2013.

- Infographic: “How the City of London finance is making us poorer”

- Rural America doesn’t have to starve to death, The Nation, looking at the geographical aspects of the finance curse, from a U.S. farming perspective, as farming yields have multiplied but farming communities have become poorer.