This blog post contextualises the new Pandora Papers leak. It explains the need for public beneficial ownership registries, it opposes the latest opinion by the EU Data Protection Supervisor on the matter, and it shows how to use recent US case law to get the names of enabler’s clients, regardless of professional secrecy. It ends with a proposal suggesting that, just as banks are required to report their account holders to authorities and intermediaries are required to disclose schemes to hide beneficial owners, lawyers and corporate service providers should start reporting the identities of the clients for whom they set up offshore structures to authorities on an annual basis.

The Pandora Papers are yet another leak that exemplify the urgent need for public beneficial ownership registries around the world. Public beneficial ownership registries are official registries or databases (eg a commercial register) which collect information on the natural persons who ultimately own, control, or benefit from any legal vehicle (eg company, trust, etc). Having a record of the natural person (or beneficial owner) behind every legal entity serves to prevent the kind of financial secrecy that enables illicit activity. When public access to beneficial ownership information is not available, the public (and in some cases, the authorities) rely on leaks to access this information. In fact, as we’ve argued in a previous blog post, public access to beneficial ownership information would make leaks obsolete. Everyone would have access to beneficial ownership data without needing to depend on whistleblowers and journalists.

Undermining transparency: the EU Data Protection Supervisor

In an act of apparent hostility toward beneficial ownership transparency, which started gaining public support after the Panama Papers and the Paradise Papers, the EU Data Protection Supervisor issued Opinion 12/2021 on 22 September 2021 in which they expressed opposition to the growing movement for public access to beneficial ownership information as enshrined in the EU 5th Anti-Money Laundering Directive (AMLD 5). (This non-binding opinion is about the “AML legislative package” adopted by the EU Commission on 20 July 2021, which among other items, reiterates the call for public access to beneficial ownership information as established in AMLD 5).

The EU Data Protection Supervisor (EDPS) concluded the following:

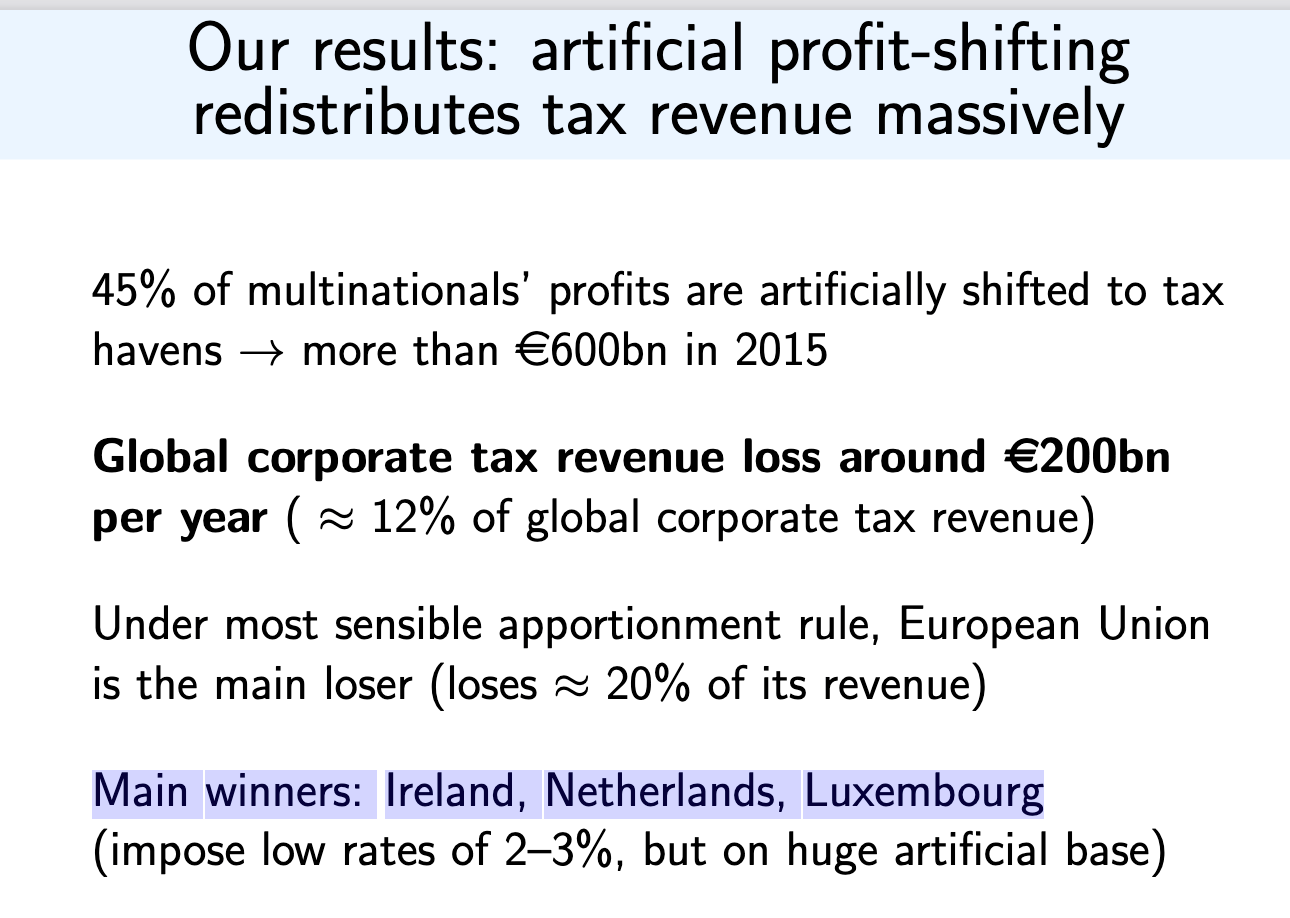

As we have described in the UN High-Level FACTI Panel background paper on beneficial ownership transparency, disclosing information on beneficial owners is critical for tackling many types of illicit financial flows. Although money laundering and terrorist financing are important issues, so are tax abuse, corruption, unjustified enrichment, bid rigging, conflicts of interest, etc. In fact, the trend now is towards using data such as automatic exchange of banking information under the OECD’s Common Reporting Standard both for tax and money laundering cases (eg Punta del Este Declaration, page 6), rather than restricting access for just one purpose.

The worst part of Opinion 12/2021, however, is that, despite acknowledging the role of civil society organisations and the media in the fight against illicit financial flows and the fact that more EU countries are establishing public online registries of beneficial ownership, the Opinion still discourages public access until another study is done to assess proportionality and other issues. Creating a commission to discuss an issue and adding as many people as possible is a commonly-known disingenuous tactic for preventing further action.

In light of this opposition to public access to beneficial ownership information, it’s worth remembering, as explained here, that no one is obliged to create companies or other structures. If individuals do not wish for their identities to be disclosed or leaked from service providers, they could operate in the economy or hold assets under their own name. Agreeing to beneficial ownership transparency should be the least of the conditions under which individuals are permitted to set up legal vehicles which operate in the economy on their behalf, own assets, etc.

This transparency requirement is especially relevant if the individuals involved will also benefit from limited liability. What’s more, most companies have very simple structures (eg 85 per cent of UK companies are directly owned by individuals or by a company which in turn is directly owned by an individual). This means that in most cases, the shareholder (legal owner) and the beneficial owner are one and the same. In addition, most countries give public access to legal ownership information (after all, many commercial registries are called “public mercantile registries”) because this was considered necessary for trade. In other words, information on the individuals who own a business was made publicly available so that investors could know who they are dealing with.

Therefore, given that for most companies the beneficial owner and the legal owner coincide, beneficial ownership information has technically been publicly available in regular mercantile registries that disclose shareholder information. Beneficial ownership registries become relevant only when individuals set up complex ownership structures, including the integration of foreign entities (mostly from secrecy jurisdictions) into the ownership structure. These complex ownership structures make it impossible to determine the beneficial owner by looking at the local commercial register alone. An attempt to restrict public access to beneficial ownership information distorts the level playing field in local economies to benefit offshore investors/vehicles.

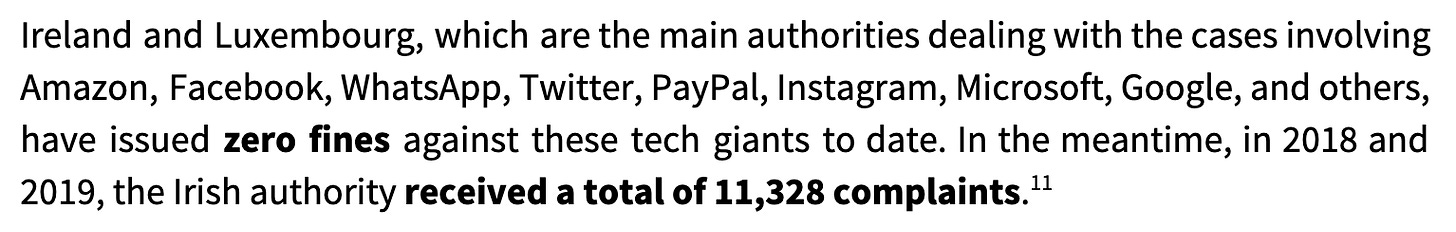

Moreover, contrary to this opinion which undermines the case for public access, it’s worth remembering that the Panama Papers, Paradise Papers – and most likely as will the Pandora Papers — have proven time and again the same fact: it’s not that “NGOs and the investigative journalism de facto contribute to drawing attention” to money laundering, but rather that they are indispensable to addressing illicit financial flows within our current framework. Sadly, media articles are sometimes the only real sanction that wrongdoers face and the only source of information on the users of secrecy jurisdictions.

Many authorities have had access to beneficial ownership information in (confidential) registries for years. They have also had access to data held by local financial institutions. The UK even has access to the beneficial ownership registries of some of the most problematic secrecy jurisdictions including the Cayman Islands and the British Virgin Islands (both ranked among the worst offenders by the Financial Secrecy Index), because they happen to be UK dependencies. Yet, this data is rarely used proactively. Investigations by government authorities mostly happen after a leak and many times as a result of the leak. These government actions in the aftermath of leaks may be because some governments (especially in lower income countries) didn’t have access to the data prior to the leak. In other cases, however, it may be that authorities only felt pressured to take action after the leaks became public.

Access to beneficial ownership information by the media and NGOs is so important because, other than some politicians resigning, the consequences of these leaks from law enforcement do not result in bankers, lawyers, or other enabler – let alone politicians – going to jail en masse. In other words, it’s not that Civil Society Organisations (who help the media understand and contextualise data) and investigative journalists simply help law enforcement by providing the information they need to administer consequences. It’s that their work alone may be the only type of “enforcement” that takes place (reputational risk as a result of negative press). Politicians and elites may be more discouraged from using secrecy jurisdiction because of leaks than for the fear of law enforcement.

Just as the Panama Papers led to the EU 5th Anti-Money Laundering Directive, which required public access to beneficial ownership information, the Pandora Papers demonstrate the need for beneficial ownership information to be publicly accessible in all countries, starting with major secrecy jurisdictions and financial centres. This would enable these “NGOs and investigative journalists”, as well as authorities from all over the world, to conduct investigations year round rather than depending on leaks.

What is being done and what is missing

As our paper the State of Play of Beneficial Ownership describes, by April 2020 more than 80 jurisdictions had approved laws requiring beneficial ownership data to be disclosed to a government authority. Public access, albeit still limited, is now growing in Europe (not just in the EU, but also in British dependencies, Eastern Europe, and especially in the Western Balkans). To continue moving in the right direction, however, authorities need to invest more in developing verification mechanisms and closing loopholes. Beneficial ownership will not be useful if there are pathways for certain types of legal vehicles to avoid registration (eg most laws do not cover listed companies and investment funds) and if there are too many exceptions, as is the case in the US. Moreover, establishing beneficial ownership registries just for legal persons but not for trusts misses the point, given that trusts are weapons of mass injustice and have been documented again in Pandora Papers to be vehicles of choice for illicit financial activities.

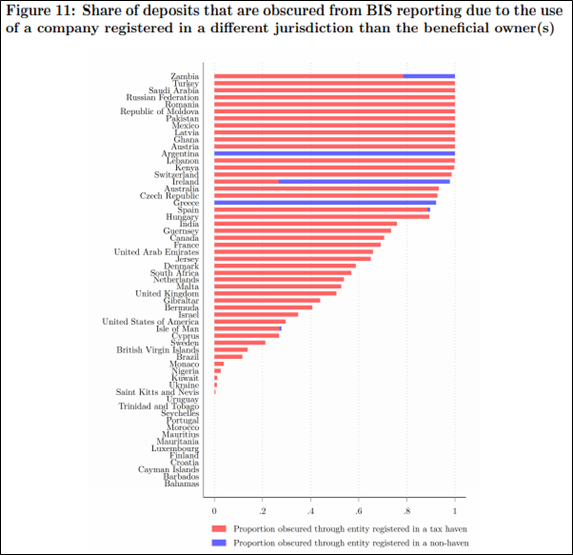

Apart from major loopholes to the scope, a big impairment to data accessibility is based on limited triggers. In other words, the parameteres for when beneficial ownership data must be registered and whose data must be registered are not inclusive enough. As explained in this brief (see page 18, proposal 4), most countries require only local legal vehicles (eg companies) to register their beneficial owners, but don’t demand this from foreign entities that may be operating in their territories or whose beneficial owners may be local residents. In other words, even a super advanced beneficial ownership register like Denmark’s would have no data on what was revealed by the Pandora Papers. The Danish register would know about Danish companies, but not about offshore companies set up by Danish residents in secrecy jurisdictions.

Until public beneficial ownership registries are available all around the world, each country should require beneficial ownership registration not just from locally incorporated legal vehicles, but also from any foreign legal vehicle with operations or assets in their territory, and from any legal vehicle that has a local participant, be it a beneficial owner, shareholder, director, etc. In other words, Denmark’s beneficial ownership register should collect beneficial ownership information on any Danish legal vehicle, as it does. But it should also collect information on any foreign legal vehicle with assets or operations in Denmark and any foreign legal vehicle in which a Danish resident participates as either a shareholder, director, beneficial owner, settlor, etc. (There are some disclosure regimes, either asset returns for public officials or asset and income returns for tax authorities, which already target offshore holdings, so expanding triggers of beneficial ownership registration is not that different to what already exists).

However, even though a country with such comprehensive scope and trigger criteria would in theory have all the relevant information (because the law would require it), the accuracy of the registered information as well as the enforcement of its registration is a completely different issue. For this reason, countries should undertake additional measures:

- Country of residence as a structured data to be searched for or exchanged

While many countries have established public online beneficial ownership registries, search mechanisms may be limited. A user may need to know the exact name of an entity, or may only do a (free) search by an entity’s name or ID. Some countries also allow users to search for information by the beneficial owner’s name or ID. What is needed, however, is the capacity to search by country(ies) of residence. This way, a countries could search for information on all their residents across every country’s public beneficial ownership registry, rather than trying to search for every individual taxpayer to see if they are mentioned as a beneficial owner. Countries without public access to information should engage in automatic or spontaneous exchanges of this information with the country of residence of the beneficial owner.

- Using offshore banking data to reveal offshore strategies

As proposed by our latest blog post on the leak from a bank in the Isle of Man, offshore banking data – especially what must be exchanged under the OECD’s Common Reporting Standard for automatic exchange of financial account information – could be a game changer for authorities. Data on offshore accounts, in addition to disclosing undeclared monies, could be used to reveal offshore secrecy strategies by determining the preferred secrecy jurisdiction used (or abused) by local taxpayers. Exchanged banking information could also reveal the types of structures typically chosen (a company, a trust, an Anstalt, etc) by residents of a particular country. For instance, based on a very small sample, the blog post described that 70 per cent of British beneficial owners used discretionary trusts from Cyprus to hold their bank accounts in the Isle of Man. A systematic analysis by authorities of the information received through automatic exchanges could reveal patterns that allow authorities to focus resources on obtaining data or establishing countermeasures in the secrecy jurisdictions favoured by their taxpayers.

- Obtain client information en masse directly from enablers

One of the conclusions of the Pandora Papers is that despite the many leaks, enablers such as lawyers and trust and company service providers (TCSPs) keep helping criminals and high net worth individuals hide behind secretive structures to engage in illicit financial flows including tax abuse and corruption. The Financial Action Task Force (FATF) in Recommendation 22 requires Designated Non-Financial Businesses and Professions (DNFBP) such as lawyers, notaries, and accountants to conduct customer due diligence and be subject to anti-money laundering rule. However, not all countries require this from their service providers. Even for those that try to require it, lawyers are especially prone to resistance, often invoking professional secrecy based on attorney-client privilege, which can be abused to engage in illicit financial flows in general, as well as to avoid automatic exchange of banking information.

On the bright side, however, a recent US case law (Taylor Lohmeyer Law Firm PLLC v. United States of America, Civil Action No. SA-18-1161-XR, 15 May 2019) that we blogged about gave access to the US tax authority, the IRS, to the identities of clients of a law firm that had engaged in creating offshore structures to enable abuse of US taxes. Importantly, the decision was also upheld by the US Court of Appeals in 2020. Here are some interesting remarks:

It’s ok to ask for client information from a law firm engaging in creating offshore structures to hide the beneficial owner:

“The clients of [the Firm] are of interest to the [IRS] because of the [Firm’s] services directed at concealing its clients’ beneficial ownership of offshore assets”.

It’s also ok for the purpose of identifying unknown clients who have also obtained the services:

“The IRS is pursuing an investigation to develop information about other unknown clients of [the Firm] who may have failed to comply with the internal revenue laws by availing themselves of similar services to those that [the Firm] provided to Taxpayer-1”

This is the data that the IRS asked for:

“Documents “reflecting any U.S. clients at whose request or on whose behalf [the Firm] ha[s] acquired or formed any foreign entity, opened or maintained any foreign financial account, or assisted in the conduct of any foreign financial transaction”; “[a]ll books, papers, records, or other data . . . concerning the provision of services to U.S. clients relating to setting up offshore financial accounts”; and “[a]ll books, papers, records, or other data . . . concerning the provision of services to U.S. clients relating to the acquisition, establishment or maintenance of offshore entities or structures of entities.”

Given that the identity of the disclosed client would not necessarily incriminate them, attorney-client privilege does not apply:

“This broad request, seeking relevant information about any U.S. client who engaged in any one of a number of the Firm’s services, is not the same as the Government’s knowing whether any Does engaged in allegedly fraudulent conduct, or the content of any specific legal advice the Firm gave particular Does, and then requesting their identities.”

Based on the success of this US case, all countries should not only follow and try similar lawsuits, but they should also establish by law that, just as banks and financial institutions are required to report the identities of their accounts holders and beneficial owners, law firms and corporate service providers in general should annually report the identities of all their clients for whom they set up (or help set up) legal vehicles. These regulations should focus especially on service providers who set up offshore structures (entities incorporated in a country different from the residence of the beneficial owner). In relation to this, the OECD already called on countries to obtain more beneficial ownership information by publishing Model Mandatory Disclosure Rules on Schemes to Hide the Beneficial Owner. Based on this framework, authorities trying to catch wrongdoers should be asking not just for the scheme details but also for the identities of those clients who may have used these schemes.

Establishing such a requirement by law may also undermine any attempt to invoke professional secrecy to oppose disclosing clients. Another US case, United States v. BDO Seidman, dealt with this subject matter. This case was based on US tax regulations requiring organisers of tax shelters to register tax shelters with the tax administration. The regulations also required organisers and sellers of such shelters to keep lists of their investors. (For background information on such rules, see indicator 13 in the Corporate Tax Haven Index which monitors such disclosure rules.) In the United States v. BDO Seidman case, the US tax administration (the IRS) requested the identities of the clients because “the IRS received information suggesting that BDO [the tax advice firm] was promoting potentially abusive tax shelters without complying with the registration and listing requirements for organizers and sellers of tax shelters”.

Although the clients (the “Does”) opposed the disclosure of their identities based on professional secrecy, the US Court of Appeals concluded:

“The Does have not established that a confidential communication will be disclosed if their identities are revealed… Disclosure of the identities of the Does will disclose to the IRS that the Does participated in one of the 20 types of tax shelters… It is less than clear, however, as to what motive, or other confidential communication of tax advice, can be inferred from that information alone”

This case shows why it is important to have a regulation requiring the disclosure of at least the schemes:

“At the time that the Does communicated their interest in participating in tax shelters that BDO organized or sold, the Does should have known that BDO was obligated to disclose the identity of clients engaging in such financial transactions. Because the Does cannot credibly argue that they expected that their participation in such transactions would not be disclosed, they cannot now establish that the documents responsive to the summonses, which do not contain any tax advice, reveal confidential communication.”

Conclusion

As explained here, no one is obliged to create companies or other structures. If individuals do not wish for their identities to be disclosed or leaked from service providers, they could operate in the economy or hold assets under their own name. Beneficial ownership transparency should be the least of the conditions under which individuals are permitted to set up legal vehicles which operate in the economy on their behalf, own assets, etc. This transparency requirement is especially relevant if these individuals will also benefit from limited liability. After three major leaks, it’s high time for countries to speed up the establishment of public beneficial ownership registries. In the meantime, they must start using existing exchanges of information to obtain and verify data. These leaks, however, also prove that more is needed. Not only should schemes to hide beneficial owners be disclosed to authorities by intermediaries as proposed by the OECD and the EU, but the identities of the clients potentially using these schemes should also be part of corporate service providers’ annual reporting to authorities.