Andres Knobel ■ Isle of Man banking data leak reveals how sharing data can identify offshore strategies and improve beneficial ownership

Beneficial ownership transparency is a crucial strategy for tackling illicit financial flows. It involves identifying the individuals (natural persons) who ultimately own, control, or benefit from a legal vehicle like a company, trust or partnership. Individuals engaging in illegal or illegitimate activities, however, find it quite easy to hide themselves behind legal vehicles, which are set up in tax havens (or as we prefer to call them, secrecy jurisdictions).

Although many countries are approving laws to establish beneficial

ownership registries (our report on the State of play of play of beneficial

ownership registration counted more than 80 countries by April 2020),

many challenges remain. Those challenges include difficulty in the

verification of registered ownership information as well as the

enforcement of registration requirements. Additionally, however, most

beneficial ownership registration laws are flawed from the onset by

requiring transparency just for local entities. This means that countries

have no guaranteed access to beneficial ownership information on

foreign entities operating in their territories nor on the foreign entities

operating abroad but controlled or owned by local individuals.

Given that banks must also collect beneficial ownership information as

part of their due diligence process whenever a customer opens an

account, they can help verify beneficial ownership information contained

in central registries. If a country has failed to establish a beneficial

ownership registry, banks may be the only source of beneficial

ownership data. However, authorities are usually able to ask for this

information from local banks only, not foreign ones.

The sharing of information held by foreign banks would be crucial, not

just for uncovering the location of money held offshore, but also for

identifying the offshore strategies used by local individuals to hold this

money. Authorities could then determine whether individuals are

holding their foreign assets in their own name or through offshore

entities. By identifying the most commonly used secrecy jurisdictions

and the preferred types of legal vehicles (eg company limited by shares,

discretionary trust, etc), authorities would have a better understanding

of where to focus their resources in order to find secret assets and

income held offshore.

Unfortunately, the current system for the automatic exchange of bank

account information, based on the OECD’s Common Reporting Standard

(CRS), provides limited data. We know, however, that this data is

already collected by banks. It could be disclosed for analysis, as we have

been calling for since 2017, in a template such as this.

Our template offers a theoretical explanation of how to analyse and

utilise shared international banking data, but at the time of publication

in 2017, we didn’t have any examples to demonstrate with. That all

changed when economist Matt Collin at the Brookings Institution

published a brilliant paper this year titled “What lies beneath: Evidence

from leaked account data on how elites use offshore banking”. Collin

uses a leak from a private bank on the Isle of Man to analyse several

interesting patterns regarding offshore financial behaviour. One of these

patterns that caught our attention in relation to beneficial ownership

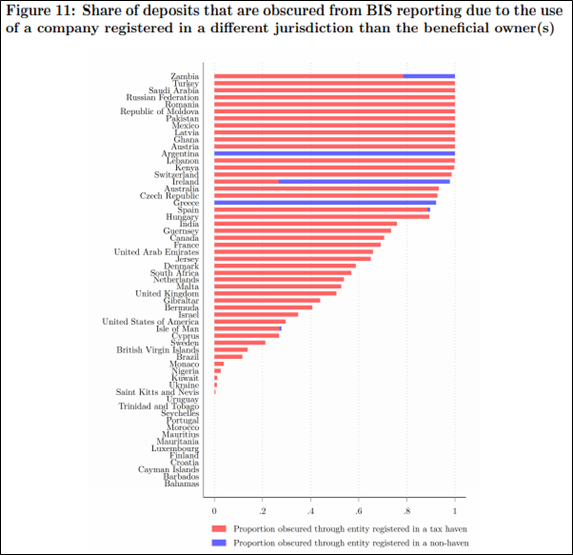

transparency is illustrated below in Figure 11, as it is labelled in the

paper.

This table shows that the Bank for International Settlements’ (BIS)

statistics on foreign deposits by country of origin may be misleading due

to data being reported at the account holder level instead of the

beneficial ownership level. In other words, if Joanne from France set up a

shell company in the Cayman Islands (with no operations, no office, no

employees or equipment), and holds a bank account in Luxembourg

through this shell company, the Bank for International Settlements’ statistics will report the Luxembourg account as belonging to a party in

the Cayman Islands, even though it really belongs to Joanne in France.

(The Bank for International Settlements’ statistics for many countries

don’t even differentiate between accounts held by individuals or

entities– all are reported together).

While the issue of misleading statistics is very relevant, our interest was

to know more about the entities used to hold the bank accounts: where

they were incorporated (in which secrecy jurisdiction) and their type (a

company, trust, partnership, etc).

It was extremely helpful of Matt Collin to share statistical data from the

leak with us. No names or account numbers were shared, only the

number of accounts based on the residence of the beneficial owner and

other details.

Results

Before we go into the findings, some caveats must be mentioned. First,

this is a leaked database from a small private bank, which doesn’t

include all the details the bank may have on each customer, and which

may involve errors (eg if the bank recorded the information incorrectly

or if the customer declared wrong information). The data contained in

the leak is obviously not representative of the whole world. Our point,

however, is not to draw conclusions about global offshore strategies, but

to show what could be done – and how – if this analysis were conducted

across the whole of the banking data that is being exchanged under the

OECD’s automatic exchange system.

Second, our focus is on how the Isle of Man is used by beneficial owners

from elsewhere in the world in their offshore strategies, so first we

excluded all beneficial owners from the Isle of Man. In addition, we

excluded all accounts with a beneficial owner using an entity from their

country of residence to hold a bank account in the Isle of Man. In other

words if Joanne from the France held her bank account in the Isle of Man

through a French company, this was excluded because both Jane and

the company are from the same country: France (in this case, Joanne

didn’t go offshore to set up a company). Instead, if she held the bank

account in the Isle of Man through a company in Luxembourg, this was

considered. In essence, we removed from the sample cases where the

beneficial owner and the company are from the same country.

Third, given the potential bias for having a local entity in the same place

where you hold your offshore bank account (this may be a package

offered whenever you set up an offshore company), we excluded

entities from the Isle of Man, which represented 67 per cent of all the

offshore cases. If Joanne from France held the bank account in the Isle of

Man through an Isle of Man entity, this was excluded. The strong

assumption here is that if the bank account was not in the Isle of Man,

then we would expect a much lower percentage of Isle of Man entities.

We may be wrong, however. It may be case that the Isle of Man is

indeed the preferred secrecy jurisdiction of the world to set up an

offshore entity, regardless of where the money will be held, either in the island or anywhere else. In essence, we removed from the sample cases

where an entity from the Isle of Man was used to hold the account in the

Isle of Man.

Finally, we disregarded cases where the entity was “unknown” or had an

invalid value. To sum up, this is what we removed from the sample on

“offshore strategies”:

- Beneficial owners from the Isle of Man, because the bank account was in the Isle of Man so it’s not an offshore strategy

- Beneficial owners who use an entity from their country of residence (a French beneficial owner using a French company) to hold the bank account in the Isle of Man, because again this is not an offshore entity

- Beneficial owners (from any country) using an Isle of Man entity to hold the Isle of Man bank account (here we assume there is a bias in favour of using an entity from the same country as the bank account, so this would overstate the relevance of the Isle of Man as the preferred tax haven to set up entities)

- Unknown or invalid values

This is what we found:

- The sample involved 249 bank accounts indirectly held by beneficial owners from 36 countries. These owners held their accounts not through their own names, but through offshore entities. It’s possible that the number of countries where the beneficial owners are apparently resident may be inaccurate due to several of these countries themselves being secrecy jurisdictions: Belize, Cayman Islands, Cyprus, Gibraltar, Guernsey, Hong Kong, Jersey, Seychelles, Singapore, Switzerland and the UAE. On the one hand, it could be the case that rich individuals from these secrecy jurisdictions (eg the Cayman Islands) are holding their accounts in the Isle of Man, in which case there are no inaccuracies and the 36 countries of residence identified among the beneficial owners are genuine. On the other hand, the more likely case is that the account holder lied on their documents and (wrongly) declared a nominee from the Cayman Islands as the beneficial owner. In this case, we have no clue as to the real residence of the beneficial owner. A third alternative explanation is that this is just a mistake by the bank when recording the data.

- The beneficial owners from these 36 countries used entities from 17 offshore jurisdictions: 45 per cent from Cyprus, 18 per cent from the British Virgin Islands, 9 per cent from the UK, 7 per cent from St. Kitts and Nevis, 4 per cent from Seychelles, and another 4 per cent from Switzerland.

- The most common types of legal vehicle used to hold the 249 accounts in the data sample included private companies limited by shares (45 per cent) and discretionary trusts (35 per cent). Most of the private companies limited by shares were from the British Virgin Islands, followed by Cyprus and the UK. Most discretionary trusts were from Cyprus followed by St. Kitts and Nevis. As described in our paper Trusts: Weapons of Mass Injustice?, Nevis offers one of the most abusive types of offshore trusts.)

If we had had a large enough sample, these could have been valid global conclusions. For example, it would be possible to conclude that Cyprus and the British Virgin Islands are the preferred secrecy jurisdictions in which to hold bank accounts. In turn ,country authorities would know to be especially wary of private companies from the British Virgin Islands, Cyprus and the UK, as well as discretionary trusts from Cyprus and St. Kitts and Nevis. Country authorities could also learn which secrecy jurisdictions and types of entities are most often utilised by their local taxpayers to hide their wealth.

This all goes to show the leap in tax transparency that can be achieved, and the better equipped country authorities can be to tackle global tax abuses, if the data collected under automatic exchange of bank account information was publicly disclosed and properly analysed using our template.

Here are some of the more detailed findings we obtained by applying our analysis template to the small data sample (the number in parenthesis refers to the number of beneficial owners in the database):

- In Africa, beneficial owners from Ghana (4), Nigeria (1) and Zimbabwe (1) used offshore companies from the British Virgin Islands, Seychelles and the UK respectively.

- In Latin America, beneficial owners from Argentina (1), Brazil (1), Costa Rica (2), Mexico (1) and Paraguay (1) mostly used offshore companies from other countries in their region with a history of being tax havens: Uruguay, the British Virgin Islands, Panama and Belize respectively.

- In Southeast Asia, beneficial owners from India (4) and the Philippines (3) used offshore companies from the British Virgin Islands, Malta and Jersey respectively.

- In the EU, the choice of tax havens and types of entities is more diverse. Beneficial owners from Czechia (6), France (1), Greece (1), Hungary (1), Latvia (1), Spain (6) and Sweden (6), mostly used offshore companies from the UK, the British Virgin Islands, Cyprus, Belize and Seychelles. However, beneficial owners from Latvia (1) and Sweden (1) also used discretionary trusts from St. Kitts and Nevis. Seventy per cent of beneficial owners from the UK used offshore trusts to hold their accounts, mostly via Cyprus, St Kitts and Nevis and the Cayman Islands. Oddly enough, the leaked data shows some UK beneficial owners using trusts from Switzerland to hold their bank accounts despite it not being possible to create a trust under Swiss law. It may be that in all these cases, the data refers to the location of the trustee, rather than the governing law of the trust.

To stress the relevance of this data one last time, consider the following. If Indian authorities had access to this data regarding all of their residents’ offshore holdings (not just for the 4 Indians mentioned in the leaked database), they would know which secrecy jurisdictions to prioritise safeguarding against, either by signing agreements to exchange information, making requests for information, or including those jurisdictions in their secrecy jurisdiction list.

Conclusion

In conclusion, banking data can provide very useful insights, if properly analysed, to reveal offshore strategies. This in turn would indicate where authorities should focus their efforts towards financial transparency and curbing tax abuse. Based on the example of the Isle of Man banking leak, the OECD’s automatic exchange of information system could become a great source, provided it broadens the scope of information exchanged. For more background information on beneficial ownership and automatic exchange of information, and an explanation on how both systems can be improved to reveal offshore strategies, please see our brief via the button below.

Related articles

One-page policy briefs: ABC policy reforms and human rights in the UN tax convention

The Financial Secrecy Index, a cherished tool for policy research across the globe

When AI runs a company, who is the beneficial owner?

Insights from the United Kingdom’s People with Significant Control register

13 May 2025

Uncovering hidden power in the UK’s PSC Register

Vulnerabilities to illicit financial flows: complementing national risk assessments

New article explores why the fight for beneficial ownership transparency isn’t over

Do it like a tax haven: deny 24,000 children an education to send 2 to school

Asset beneficial ownership – Enforcing wealth tax & other positive spillover effects

4 March 2025