Welcome to the latest episode of the Tax Justice Network’s monthly podcast, the Taxcast. You can subscribe either by emailing naomi [at] taxjustice.net or find us on your podcast app. All our podcasts are unique productions in five languages: English, Spanish, Arabic, French, Portuguese. They’re all available here. In this edition of the Taxcast:

We’re experiencing the hottest global temperatures ever recorded. For millions of us, the climate crisis is already hitting hard. And we need to know, we must know – WHO are the beneficial owners of the climate crisis? It’s surprisingly difficult to find out…

Featuring:

- Franziska Mager, Senior Researcher and Advocacy Lead (Climate & Inequalities), Tax Justice Network

- Dario Kenner, Visiting Research Fellow at the University of Sussex and author of the book Carbon Inequality

- Victor Galaz of the Stockholm Resilience Centre

- Peter Ringstad of Tax Justice Norway

- Andres Knobel, Lead Researcher (Beneficial Ownership), Tax Justice Network

- George Monbiot, Environmental campaigner and journalist

- Kenya’s President William Ruto

- Hosted and produced by Naomi Fowler of the Tax Justice Network

Transcript available here (some is automated)

“The emissions that are attributable to investments in polluting companies and sectors are estimated to be so, so, so much higher in volume than those consumption emissions for the majority of people. The regulation that is needed and that we’re asking for only pertains to a very small group of people on the whole, which makes it a very attractive policy option for most people.” ~ Franziska Mager, Tax Justice Network

“The most important thing when it comes to the richest people and climate change is their political power capturing governments, shaping policy, shaping laws. The fact that the tax havens are still open is a demonstration of their power and likewise for the polluter elite who derive their wealth and their luxury lifestyles from polluting activities, they are the ones who are using everything they can to block governments at national, regional and local level from basically pushing forward cleaner and greener technologies which would mean that the companies they’re invested or they own permanently lose market share, that’s what terrifies them. And that’s why, the political power of the polluter elite is so important to focus on and to counter. To actually shift things, you have to challenge the power.” ~ Dario Kenner, Carbon Inequality and the Polluter Elite Database

Further reading:

Beneficial ownership and fossil fuels: lifting the lid on who benefits: https://taxjustice.net/2023/06/30/beneficial-ownership-and-fossil-fuels-lifting-the-lid-on-who-benefits/

Delivering climate justice using the principles of tax justice: a guide for climate justice advocates https://taxjustice.net/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Policy-brief-climate-justice_2206.pdf

Carbon Majors Report: https://cdn.cdp.net/cdp-production/cms/reports/documents/000/002/327/original/Carbon-Majors-Report-2017.pdf

Links to Dario Kenner’s work: The Polluter Elite Database: https://whygreeneconomy.org/the-polluter-elite-database/

Carbon Inequality: the role of the richest in climate change https://uk.bookshop.org/p/books/carbon-inequality-the-role-of-the-richest-in-climate-change-dario-kenner/2920056?ean=9780367727666

Lobbying and other tactics of big oil companies to delay the transition away from fossil fuels https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2021.102049

Why we need to look at how global oil and gas industry lobbies G20 governments and how this is slowing progress https://www.climatechangenews.com/2021/11/16/oil-gas-avoided-censure-glasgow-26th-time-lets-not-make-27/

Post-war reconstruction involved taxing the richest: https://theconversation.com/post-war-reconstruction-involved-taxing-richest-it-could-be-a-model-for-building-a-low-carbon-economy-137717

White knights, or horsemen of the apocalypse? Prospects for Big Oil to align emissions with a 1.5 °C pathway https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2214629621001420

Carbon Billionaires, Oxfam report: https://policy-practice.oxfam.org/resources/carbon-billionaires-the-investment-emissions-of-the-worlds-richest-people-621446/

Cereal crops decimated by Europe’s heatwave https://www.thegrocer.co.uk/sourcing/cereal-crops-decimated-by-europes-heatwave/681361.article

“I thought fossil fuel firms could change. I was wrong” https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2023/7/6/i-thought-fossil-fuel-firms-could-change-i-was-wrong

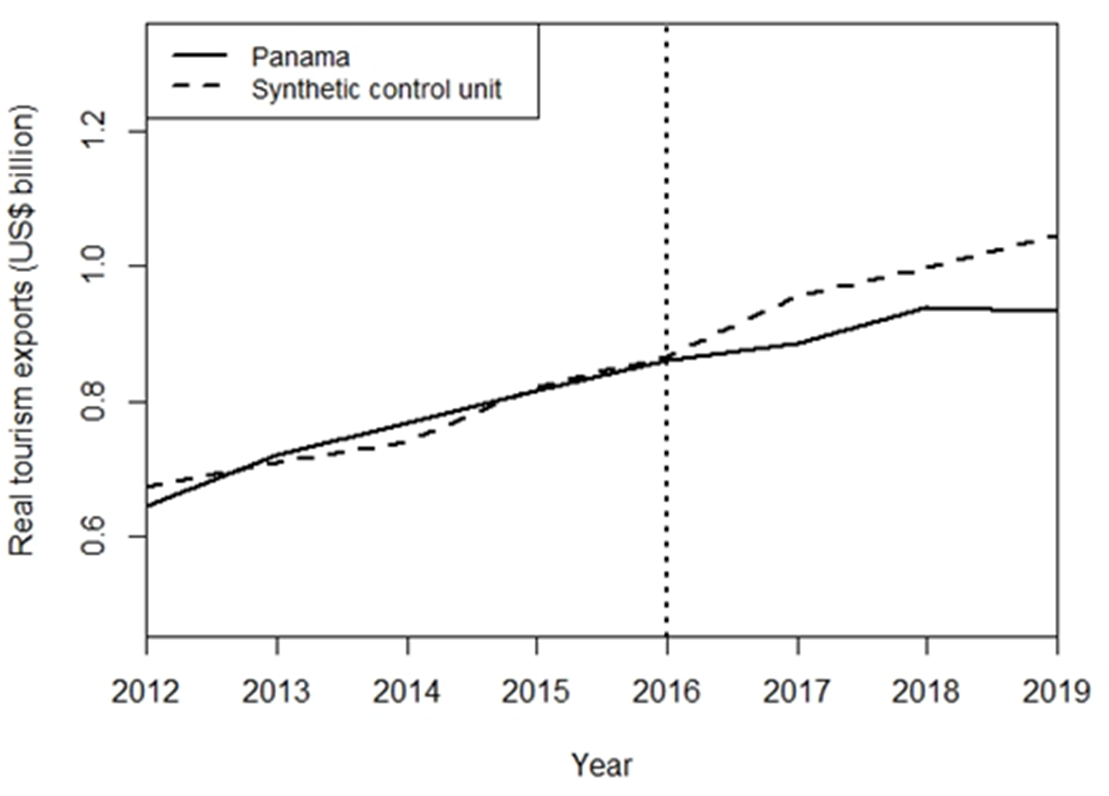

Stockholm Resilience Centre, the hidden environmental consequences of tax havens https://www.stockholmresilience.org/research/research-news/2018-08-13-the-hidden-environmental-consequences-of-tax-havens.html

New study raises red flags on tax haven role in environmental destruction https://www.icij.org/inside-icij/2018/08/new-study-raises-red-flags-on-tax-haven-role-in-environmental-destruction/

New data exposes the links between tax havens, deforestation and illegal fishing https://www.su.se/english/archive-news/research-news-archive/new-data-exposes-the-links-between-tax-havens-deforestation-and-illegal-fishing-1.396018

Summary of the Taxcast, who owns the climate crisis?

Naomi: “On this Taxcast episode: we’re seeing the hottest global temperatures ever recorded since records began. For millions of us, the climate crisis is already hitting hard, it’s already happening. And we need to know, we’ve got to know – who are the beneficial owners of the climate crisis?”

George Monbiot: “Look the clock is ticking, time is running out on the greatest crisis that we’ve ever faced, you know, we are…it’s almost unimaginable what we’re facing now and it it’s very hard to talk about it without crying because it’s the end of everything, I mean it’s the end of our hopes, our dreams, our ambitions, our loves, our hates, everything we’ve dreamt of for our children, the good world that we want for them, that could go! If, if global systems earth systems reach a tipping point, the planet will flip from a habitable state to an uninhabitable state and…I have two children and you know, every day I think – did I do the right thing..?” [Starts to cry]

Naomi: “That’s environmental campaigner and journalist George Monbiot there, getting upset during a TV interview. Because we’re in an emergency! And if we don’t know enough about who literally owns the climate crisis, it makes it harder for us to take the actions we urgently need to, not only to mitigate the damage, but also to address the inequalities that this crisis reveals, we need to do that too.

Lots of attention is going on things that can distract from the bigger picture. Almost all our attention gets focused on ‘consumption emissions’ – what we buy and use as individuals. But there are also ‘investment emissions’ – greenhouse gas emissions that only happen because people and companies are investing in them. Here’s Franziska Mager of the Tax Justice Network:”

Franziska: “I think most climate policies, or the ones that most people will have heard of are really targeted at consumption habits. So, making you change the car you drive, your, your flying habits, to make you switch energy source, and so on. And that’s really important, especially in rich countries that are massively exceeding their carbon budgets, everyone needs to make a contribution. But the emissions that are attributable to investments in polluting companies and sectors are estimated to be so, so, so much higher in volume than those consumption emissions for the majority of people.

A good way to think about it is what’s been happening to universities. So they, among others, are under pressure to make their buildings and their infrastructure more sustainable, so for example, through things like solar panels, banning single use plastic and so on, but they’re also under increasing pressure to divest from fossil fuels. And most of them sit on quite a significant amount of money and there’s pressure to put that money away from fossil fuels. So the solar panels in terms of scale, you know, will only get you so far if these universities still have portfolios or trust funds or endowment funds with high carbon content that are channelling money into future fossil fuel extraction.

And companies are made of people, the owners, the investors, the shareholders, the people who have stakes in them. Behind every company, there is a certain amount of people who own it, which will often be very difficult to track down but you know, the overwhelming majority of people in the world don’t have enough wealth to have investments, so we’re really talking about a pretty small minority of people who invest and this blurring between these two categories of companies versus individuals, in my opinion, is intentional because if you tackle the place where they overlap, which is the very, very top of the economic distribution, for example, by things like ownership transparency laws, that would really hurt and it would hurt the people who have the highest financial stakes in polluting industries the most.”

Naomi: “Of course, it’s perfectly legal to invest in activities that are causing the climate crisis. It’s socially acceptable even. This minority Franziska’s talking about – the world’s richest people – are already emitting huge and unsustainable amounts of carbon compared to the rest of us. But, unlike ordinary people, 50% to 70% of their emissions are resulting from their investments, that’s according to Oxfam. But, it isn’t that clear who these investors are, as Dario Kenner discovered. He’s Visiting Research Fellow at the University of Sussex and author of the book Carbon Inequality. He tried to identify the investors behind some of the largest oil companies:”

Dario: “So I was writing a book about carbon inequality, about the richest people, and I was mainly at the start looking at their consumption, so use of private jets and yachts and luxury cars and that kind of thing. But as I was writing that book, I realised that there was a massive part that I needed to look at which was the investment side, because it was likely to be a much bigger portion of pollution. And it is, if you think about it in terms of you know, one rich person driving one luxury car or taking private jet flights is going to be a certain amount, but investments in massively polluting companies, whether that’s, you know, oil and gas or agribusiness or whatever it is, is going to be bigger.”

Naomi: “And that’s why Dario got to work on a Polluter Elite Database:”

Dario: “I was trying to visualise the pollution of the richest to show it was more than the rest of us and to highlight that issue and try and encourage governments to pass policies and laws in that area. It was a difficult task to create this database and, and how to even get started. In my book I had to focus in the end on two countries on, on the United States and the United Kingdom but as we know, the rich are very global and that’s partly, you know, very obvious in terms of how they get around. So actually, picking two countries was, you know, it’s a bit arbitrary in some ways because the, the rich and the super-rich, they live in multiple countries.”

Naomi: “What Dario wanted to do was to quantify their ‘investment emissions’:”

Dario: “And so that’s CO2 equivalent connected to a person’s shareholdings in, in different companies or other types of wealth. I couldn’t do it for, you know, for every rich person in the world, or even for the billionaires, it’s basically very, very difficult to find out that kind of information. Even the rich lists that are compiled by Bloomberg and others, they have their own in-house teams to do that work and to track and to make calculations. I didn’t have those resources, or those kinds of information about what was happening, which you can’t find online, so I had to start with companies. So I thought, well, what are the most polluting companies in the world?”

Naomi: “So, Dario used as his starting point something called the Carbon Majors Database which gathered data on 100 fossil fuel producers and nearly 1 trillion tonnes of greenhouse gas emissions:”

Dario: “So I started with that, the 100 most polluting companies, mostly oil, gas, coal, cement, things like that. And so I was using annual reports, so for example, Shell’s annual report, there is some information disclosed in that report that has to be disclosed, that will be for the executive team, so the CEO and those other senior members of staff and then for the directors, and then the institutional investors, so like BlackRock and Vanguard and so any investor that holds more than 5% shareholding has to, basically is listed in the annual report so that’s why I could see that they were shareholders. And then for all of those, so for those individuals and directors and executive team and then for an institution like BlackRock I then had a, used a methodology which was, had been used to estimate portfolio emissions. I applied that to either the individual or say to BlackRock and basically calculated their, based on their shareholding, their percentage of, say, Shell’s emissions for 2016, for example.”

Naomi: “But despite his efforts, Dario could only account for 12.08% of the shares owned. Most of them belonged to two massive investment funds: BlackRock and Vanguard. So, we don’t know who the individuals are who ultimately hold the remaining 88% of shares:”

Dario: “Well, yes, it’s just a massive black hole. Who, who knows?! So it’s very unsatisfying only being able to present a short list of names and then say ‘BlackRock’ as well because, yeah, who are the other investors, basically?!”

Naomi: “Perhaps it’d be less socially acceptable to invest in activities like this that are fuelling the climate crisis if the identities of all investors were public, who knows? And of course, it’s hard to trace those investing in and profiting from illegal climate crisis activities too. As Peter Ringstad of Tax Justice Norway says here, tax havens, financial secrecy and weak data on ownership isn’t just an inequality challenge to societies and a threat to economies, it’s also directly putting in danger the continuation of human life on a habitable planet:”

Peter: “We’re currently living in a dramatic time of profound changes in human history and the history of our planet. The full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022 by Russia. As dramatic is the severe biological and ecological pressures that our Earth is being put under by human activities such as the destruction of vital and precious rainforests. The war in Ukraine and the destruction of our environment are committed for the purpose of gain – gain of power, gain of status, but most often the gain of money facilitated by an enabling environment – the elaborate international financial system of tax havens and professionals. This is the common denominator between Russian oligarchs that are evading sanctions and companies that contribute to harmful or illegal logging of rainforest. They’re all aided by the services in tax havens and are inextricably linked to the world’s largest crisis and can prevent us from effectively solving these problems.”

Naomi: “There’s all sorts of illegal and perfectly legal money-making going on that has to stop. Financial transparency sheds light on all of them. There are people, banks, institutions lending money to, insuring, banking and investing in the fossil fuel economy, individuals all the way along the feeding chain who’re getting very wealthy from it, at our very great cost. Researcher Victor Galaz of the Stockholm Resilience Centre studied the links between tax haven use and deforestation of the Amazon in Brazil:”

Victor Galaz: “There are something called tipping elements in the climate system meaning that there are big big systems that change incrementally up to a certain point and once you push them after that point, that tipping point, they change quite drastically and rapidly and has big impacts on the whole climate system and the Amazon rainforest is one such system. These are also known as sleeping giants, we were interested in seeing what are the connections between the financial sector and sleeping giants in the earth system. Many of these deforestation activities are linked to soy production and beef production and it’s been proven many many times that these are the two main drivers of deforestation. There are more of course, so you have mining for example that seems to be popping up as an additional big factor.”

Naomi: “Just like Dario Kenner you heard from earlier with his Elite Polluter’s Database, Victor Galaz found that accessing information on the actors involved in trashing the Amazon, some of the earth’s biggest lungs, was difficult:”

Victor: “If you want to conduct these economic activities in the Amazon you need funding right? I mean the funding is what makes all these activities operate, you need to to pay out salaries to people, you need to buy and build infrastructure etc so you need you need funding for it and it has been quite challenging to get to those numbers, to be honest I think there is a general lack of transparency in the financial sector in general just to see for example the sizes of loans, private loans to some companies. We just chose the biggest players in the soy and beef sector in Brazil and then started to look at the patterns of loans and payments to these companies that we know are prone to deforestation, so what type of capital flows are we seeing to these companies, from where in the world and which are the biggest financial intermediaries?”

Naomi: “To analyse the industries responsible for deforestation Victor Galaz used data that was made available by Brazil’s central bank – that this data was even made available was apparently unusual. And it shone a temporary light onto what he thinks is like a snapshot of practices on a global scale. What he found was that two thirds of foreign capital directed to Brazil’s soy and beef sectors between 2000 and 2011 was channelled through tax havens. And guess what? Often that’s a tax dodge too, so it’s not just potentially removing those responsible for deforestation from immediate view, as he explains here:”

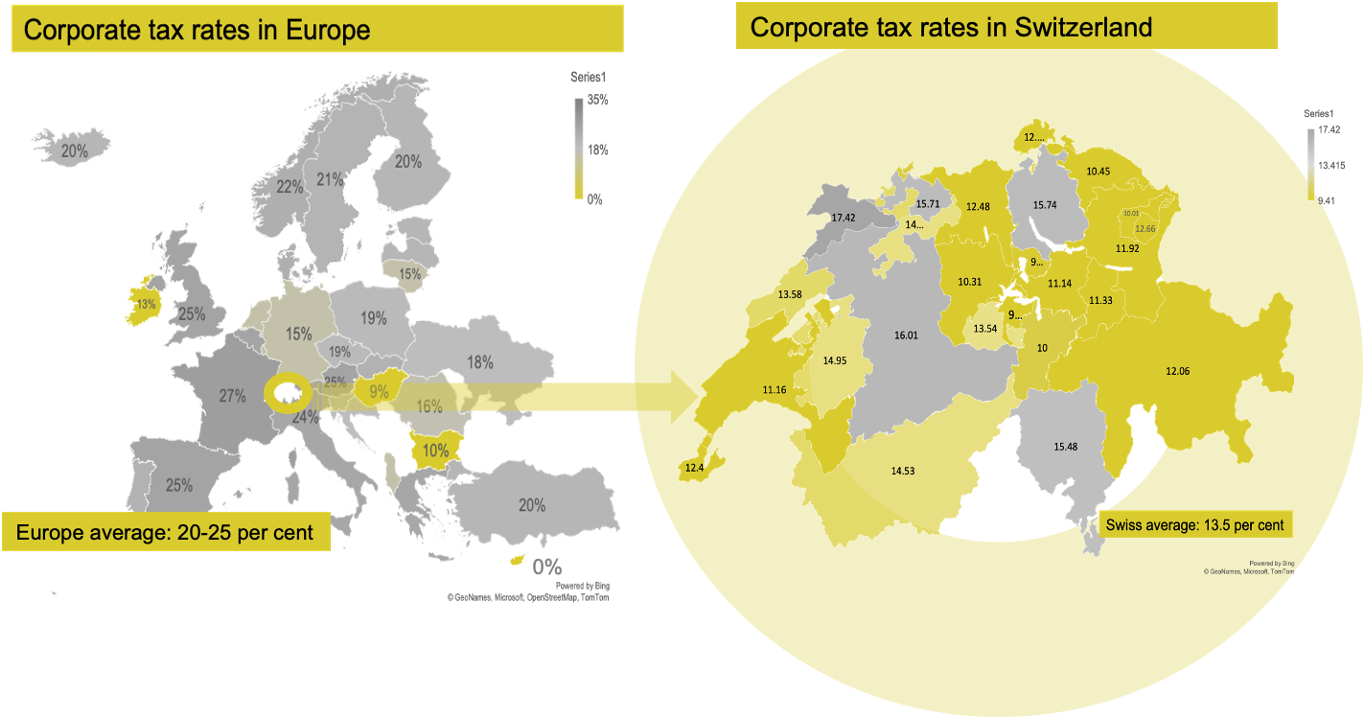

Victor: “In 2018 what we discovered was first of all substantial amounts of capital to the soy and beef sector to these companies, a lot of it going from tax haven jurisdictions, a surprisingly large amount, so 68% was transferred through tax havens, so of all international flows of capital into these companies, 68% of what we analysed was through tax haven jurisdictions. In some cases – aggressive tax planning – a few of these multinational companies received 100% of the foreign capital through their own subsidiary located in a tax haven such as the Cayman Islands – and this is a common pattern that you would see if you’re looking into aggressive tax planning, a company would place its own subsidiary in a tax haven and then instead of going out to the open capital market for a loan, it would just give itself a loan from one of the from one of its subsidiaries and by that way you would actually lower your tax rate considerably.”

Naomi: “So, that’s a double-hit to people and the planet:”

Victor: “I mean it’s quite obvious that the countries where this is happening are losing tax revenue, this is a big problem, these funds could be used for socially and environmental beneficial investments in the country, and local investment to protect local communities etc so that capital is lost to something else.

I also want to mention, I mean I just talk about corporations but there are of course connections to to wealthy individuals in Brazil as well I mean, as we did the study it was it was clear that the Minister of Agriculture in Brazil was one of the persons that appeared in the Panama Papers so there were some connections here related to influential families in Brazil, the political elite, some of them linked to these companies and the individual holding of accounts in Panama and other tax haven jurisdictions.

So, aggressive tax planning by global corporations, that’s one part of the puzzle. The other thing that we know of, and there are cases – aggressive tax evasion by smaller companies linked to illegal activities, illegal mining, illegal deforestation, sometimes connected to drug cartels, especially in South America and then you have tax evasion by elite individuals. This is a complex interaction, sometimes they interact, sometimes they don’t interact but this is what we see happening. Very difficult to get a good grip of from a scientific point of view, and this is a vicious cycle, I think it is contributing to a lot of problems that we need to address.”

Naomi: “So, again, financial secrecy, tax haven use and lack of proper ownership registers are all blocking the way here. When it comes to tax, I’ve said many times before on the Taxcast, there are what we call 5 Rs of tax: tax isn’t just about the most commonly understood R – raising revenue – another one of the 5Rs of tax is called repricing – it means we can do things like use tax to incentivise beneficial behaviours like renewable energy and disincentivise harmful activities. Another of the 5 Rs of tax is redistribution to address inequality, which climate justice also must tackle. So tax is our super-power, it’s a great tool if we use it right. But hand in hand with tax justice, we must have full transparency of ownership. Here’s Andres Knobel of the Tax Justice Network who’s done a lot of thinking and work on how a global asset registry could work:”

Andres: “A global asset registry, or even starting with national asset registries, would be the best way to tackle and address the secrecy surrounding those who benefit from climate change. The most important aspect for these global or national asset registries is to capture information at the beneficial ownership level, meaning the natural persons who ultimately own, control or benefit from fossil fuels and other emissions industries. So this means that if we had complete and comprehensive global or national asset registries, we would have information about the end-investors at the beneficial ownership level of those who are passively benefiting from companies directly involving or exploiting fossil fuels, as well as investment funds who are also investing or profiting from these type of industries. Now a global asset registry would also cover the beneficial ownership over some specific types of luxury assets that are highly contaminating, such as private jets or private yachts, as well as those who have large farmland with a lot of livestock.”

Naomi: “And nations need to work their way as fast as possible towards a global asset registry, right? What are the best ways they can do that?”

Andres: “How to get there? Countries need to start ensuring that they have asset registries for all of these type of assets from real estate, farmland, livestock, private jets or yachts. And at the same time to start interconnecting these registries with their beneficial ownership registries. And assuming that of course, these beneficial ownership registries will not cover only local companies but also foreign ones that have ownership or interests in local assets. Once we have this, it will be possible, assuming of course, the beneficial ownership definition has no thresholds and really covers everyone to finally know who are the end investors at the beneficial ownership level, who are either passively profiting or directly using and exploiting luxury assets that are responsible for much of the climate change.”

Naomi: “In other words, we need all ownership to be registered, with no cut-off point, or threshold below which owners who have a small share of a company or asset can avoid registering – that just ends up creating a loophole where ownership gets divided up artificially. So, that’s one important way forward – a global asset registry, and national asset registries. That kind of spotlight on emissions investors makes it easier to target tax policies and other measures on the right activities and people. Dario Kenner again:”

Dario: “Clearly at a time of massive economic inequality in so many countries, the rich have to pay more tax. And I mean that is blindingly obvious. And one thing is transparency and then there’s another thing which is – what do we need to do to fully address the climate crisis? And you know, there are kind of tools that can be used, but in terms of addressing the climate crisis, we have to get entire economies off fossil fuels and a bit more transparency here or there can help, but it might not lead to that economy-wide shift that quickly.”

Naomi: “Mmm, certainly not quickly enough, no.”

Dario: “The most important thing when it comes to the richest people and climate change is their political power. And that actually is the really central thing which is, is kind of obvious to say to a lot of people, but it’s maybe harder to talk about, it’s harder to see, but it’s that political power capturing governments shaping policy, shaping laws. I mean, as you will know, the fact that the tax havens are still open is a demonstration of their power and likewise for the polluter elite who derive their wealth and their luxury lifestyles from polluting activities, they are the ones who are using everything they can to block governments at every level, national, regional and local level from basically pushing forward cleaner and greener technologies which would mean that the companies they’re invested or they own permanently lose market share, that’s what terrifies them. And that’s why, the political power of the polluter elite is so important to focus on and to counter.”

Naomi: “Oh absolutely, absolutely!”

Dario: “And basically, getting in to this, what I call counting carbon – it’s great that we all know who is polluting and by how much, but actually I just think it’s important to, to be clear about the tool and what it can do but how it fits into that broader transition in terms of energy and transport, technology and food because this is a broader context that we’re operating in.

I’ve actually stopped counting carbon and shifted from carbon inequality to just focus on the lobbying by the oil and gas industry, for example, because I realised that the counting of the carbon, which is useful, we need to know who’s polluting and especially if there’s massive inequality, which there is. But I, I deliberately decided to stop that work and to look at the lobbying because that is the thing that is stopping the economy-wide shift so that we all, including the rich, have other options for energy and transport.”

Naomi: “Yeah. That makes total sense because that’s where the power lies, in the end.”

Dario: “Exactly. Exactly. And I’m sure you, you’ve seen the same on tax, you can get into all the technical part of it and transparency is absolutely fundamental, of course it is. To actually shift things, you have to challenge the power.”

Naomi: “Absolutely. And although big oil and gas companies are making all kinds of promises to somehow ‘green’ their operations, Dario believes there’ll be absolutely no transition from fossil fuels unless, he says, ‘the polluter elite who run big oil and gas companies are weakened economically, politically and morally.’ He’s currently focusing on researching how oil and gas industries have been lobbying against solar and wind energy, and electrified transport. I’ll put links to his work in the show notes.

So, financial transparency, full beneficial ownership transparency, national and global asset registries – they’re all crucial tools in targeting the power of ultimately a small number of people and large polluting companies. Tax is key. To get to the low carbon societies and economies, we need carbon tax justice that tackles the historical dominance of high emitting people, industries and nations. And greenhouse gas emissions need to be reduced while ticking three essential boxes – it’s got to be at high speed, it’s got to be in large quantities and it’s got to reduce inequality – that’s what we call the carbon tax justice triple reduction nexus, and we’re gonna cover this in detail soon on the Taxcast. Meanwhile, the world’s wealthiest nations must wake up fast to their responsibilities for the climate crisis. Here’s environmental campaigner George Monbiot again, speaking on ITV in the UK:”

George Monbiot: “the great majority of the world’s people are not having a voice in this, you know, we’re doing it to them, we with our huge carbon emissions, the amount of fossil fuel we’re burning, we’re destroying the lives of people on the other side of the world, people in Bangladesh, people in Sub-Saharan Africa people in Central America, their lives are being absolutely trashed by the way we’re just going about our daily lives, driving on the roads, not insulating our homes, producing all these greenhouse gas emissions, we are literally destroying lives at a phenomenal rate right now and those people are not represented in our decisions, they’re not represented in our political systems.”

Naomi: “Here’s Franziska Mager again of the Tax Justice Network:”

Franziska: “Most, if not all of the emissions targets and specific policies we do have now treat the climate crisis as something of this moment. A good example is something you’ve may be heard of, the Nationally Determined Contributions or NDCs. They are sort of non-binding national plans highlighting the climate change mitigation strategies that countries commit to, including their targets for greenhouse gas emissions. A lot of these strategies look forwards, and not at all backwards. A lot of these strategies draw from broadly the ‘now,’ what needs to change to stay within well, hopefully 1.5 degrees, if not two degrees. So there isn’t really a look backwards and we’ve only arrived at this point in this, you know, extreme version of climate breakdown because of the development and the industrial activities that have unfolded over the last decades, if not centuries. So if you rethink the now as something that’s a result of a cumulative phenomenon, the picture and the responsibilities change completely. Not everyone is responsible to the same degree. In fact, most people, especially in the Global South arguably have absolutely zero responsibility. And there is this sort of fork in the path we’re standing in front of right now and this perception is changing, but it is changing too slowly for what needs to happen.”

Naomi: “Not only are the world’s wealthiest nations the main culprits for the climate crisis, they got rich from colonial practices that have impoverished colonised regions to this day. That’s hampering the efforts of poorer nations to transition to net zero and tackle inequality. They continue to be drained by extractive practices through global capital markets. And what began with the exploiting of people and natural resources of colonised regions, shifted to wealth extraction through financial secrecy, tax haven networks and the twisting of global corporate taxing rights. That’s why a crucial aspect of reparational justice is for global south nations to claim their sovereign right to tax global multinationals fairly. And that’s happening now in efforts to move decision-making on international tax rules to the United Nations, led by African nations.

Countries in the global south are especially challenged when it comes to tackling the climate crisis because of their unsustainable mountains of debt. This is Kenyan President William Ruto speaking at the recent Summit for a New Global Financing Pact:”

President Ruto: “In Kenya we are paying we are paying five billion dollars every year to service our debt. If we have to deal with the climate financing in the context of what we agreed in 2015 in the consensus we built out of the Paris Agreement where we get emissions down by 45% by 2030 and Net Zero by 2050, we need 9.2 trillion dollars every year for us to get to Net Zero by 2050. We have a gap of 3.5 trillion dollars. How do we raise 3.5 trillion dollars to be able to close that gap? If we got an opportunity not to pay the five, not to pay the five 6:38 billion dollars and it is made available to us we would have money at scale. And if it was done for 10 years and we are given 20 years grace period, we would be sorted and everybody will be happy. We will still pay our debt, it has just been postponed, so the shareholders have no problem and we have immediate money to deal with our situation, so we are also not doing badly, so we can have a win-win. Hopefully before we leave here we have that agreement, I don’t think it is unfair for us to ask.”

Naomi: “Indeed, it’s not. Many would push further, from just delaying repayments to cancellation, if for no other reason than putting net zero goals first in the interests of human survival on earth – I mean, global food production is now at a tipping point for goodness sake! Franziska Mager again:”

Franziska: “You know that’s why debt cancellation are integral to climate justice, countries in the Global South, or debt ridden countries that need to transition need this debt to be gone. And I think it’s really useful to view the extreme inequality in economic distribution and the emissions that are linked to that distribution as one space for policy, not two separate spaces. There’s this term in environmental law of common but differentiated responsibilities and a lot of the climate crisis narrative very justifiably emphasises the common part of that responsibility but not everyone is responsible to the same degree. So viewing inequality and emissions together opens specific policy options and then it narrows them down to what is the most urgent, at least in the short term.”

Naomi: “So, tackling inequality and carbon emissions go hand in hand. Back to Kenya’s President Ruto and how on earth his nation can possibly both service its debt and transition to net zero. The Kenyan government raised taxes recently on fuel and housing – they say to cope with rising debt repayments. Desperate protests broke out across the country and police fired on protestors, killing two people. Truly terrible days like that are connected to the slowness of wealthier nations to act on debt and climate crisis:”

President Ruto: “We are not making progress ever since Paris in 2015 because we had a global consensus on a global problem called climate change but we tried to sort it out using national institutions that are hostage to national interests or we tried to use shareholder institutions that have shareholders who will make the decision finally. So we must get a new financial architecture around climate financing so that we can sit at the table, so there are no shareholders. We are not going in the right direction, we’re going backwards so it is urgent that we all agree on how to go forward. And why specifically do we need to target taxing fossil fuel? Because it is the fuel, it is what is contributing 73% of all global gas emissions that are causing trouble in our globe, that’s why we must go there and that is the difficult conversation we must have. Let us agree to pay the aviation tax, we have no problem, let us agree on the shipping tax and we want to pay, we don’t want anybody to pay for us, we want to pay our percentage. It is only when we raise global finances that have no national interest for any particular country or shareholder interest of any person, that is how we are going to sort out this global challenge.”

Naomi: “Franziska Mager again:”

Franziska: “I really believe that there is big potential for political parties when it comes to legislation and regulation around financial transparency, they should take this topic and really go about mainstreaming it massively and make it part of their platforms. It’s a sort of cousin to the anti-corruption rhetoric which is obviously closely related. The regulation that is needed and that we’re asking for only pertains to a very small group of people on the whole, which makes it a very attractive policy option for most people.”

Naomi: “In previous times of crisis, the world has managed to come together and take collective action. After the second world war, the mega-reconstruction that nations did involved taxing the very richest highly. The world’s nations have done things in very new and different ways when the gravity of a situation has required it. We can do it again. We have to. President Ruto again:”

Ruto: “Let me dare say the following. After the Second World War 44 countries, 740 – I think 44 – delegates sat in a small city called Bretton Wood, the Bretton Wood institutions were agreed in three weeks. The UN that we today celebrate was a conversation by 50 countries in two months. Because it was necessary. Because there were leaders that wanted and that had capacity to make decisions. Because there was, the whole of Europe had been destroyed and so it was urgent and it was important for a decision to be made. Why is it difficult for us? Are we saying the crisis that we are going through, including from Pakistan is not serious enough for us to agree on a global financing mechanism that sorts out climate change as a problem that is affecting all of us? Are we saying ever since 1945 we have become stupid, is that what we’re saying? Or we have become less human that we have no more feelings about what’s going on? Are we saying that we are incapable of making the decisions that are required of us as leaders?”

[Music]

Naomi: “That’s it for now on the Taxcast. There are more policy ideas for climate and equality justice advocates in our report ‘Delivering climate justice using the principles of tax justice,’ which are in the show notes, along with lots more further reading. Thanks for listening. I’ll be taking a break next month but I’ll be back with you after that. Bye for now.”