Andres Knobel ■ Penguins hold millions in Australian banks: revealing trends from Australian and German banking statistics

Automatic exchange of bank account information (the A of the ABCs of tax transparency) is a crucial tool to tackle offshore wealth and tax evasion by disclosing to tax authorities information on the foreign bank accounts held by each country’s taxpayers. It also provides useful data to reveal offshore strategies used by those taxpayers to hold wealth abroad. As described in this blog post and further explained in this brief, banking data can reveal information such as Latin American elites preferring companies while Brits opt for discretionary trusts.

But not everyone can enjoy the benefits of the automatic exchange of banking data. The OECD system for exchanges, called the Common Reporting Standard (CRS), still excludes lower income countries. For authorities of these excluded countries, the best they can hope for is that financial centres will publish basic statistics on bank accounts disaggregating information by country of residence of the account holder. This data is insufficient for them to determine the identity of any taxpayer, but it provides basic data for analyses and trends.

Thanks to support from the Tax Justice Network Australia and Tax Justice Network Germany, Australia and Germany published the first batch of statistics in 2020. In 2021 both countries updated their statistics regarding 2019 (Australia in a machine readable format!). Here are some highlights.

Australian statistics: account holders “resident” in uninhabited islands

Most countries require their financial institutions to collect and report information on account holders as long as they are resident in a country participating in the OECD automatic system (the rationale for this is that if the account holders are resident in a non-participating country their information cannot be shared with their authorities, so why bother collecting their data). This means that Swiss banks collect and report information on German or Brazilian account holders to authorities, but not on Bolivians because Bolivia isn’t participating in the OECD automatic system. However, Australia is among the transparency champions (together with Argentina, Estonia and Ireland) who apply the so-called “widest” approach, where information on all non-residents is collected and reported to authorities, even if authorities from these “widest” countries (eg Australia), cannot yet exchange the information on the residents from non-participating countries such as those from Bolivia.

Thanks to this disclosing of data on any non-resident (regardless of whether their country is participating in the OECD system), Australian statistics reveal a really problematic situation: Australian banks have determined that many account holders live in uninhabited islands. To understand the gravity of this, one must consider that the whole system relies on banks and other financial institutions determining the (real) residence of their account holders (usually where they live or where they are incorporated in the case of an entity, assuming that this is also where they are tax resident) and sending the banking data to their corresponding country so that authorities of those countries can verify if the foreign accounts have been reported and the corresponding taxes were paid. Determining the real residency is already challenged by the abuse of golden visas which allow individuals to pretend they are residents of secrecy jurisdictions so that their information is sent to the wrong country. Australian statistics, however, point at something worse.

As described by this article, Australian banks have identified account holders as residing in uninhabited islands including Norway’s Bouvet Island, whose “only vertebrate residents are thousands of seals, seabirds and penguins”. The account balance corresponding to Bouvet Island amounts to more than 2.4 million Australian dollars. In addition, close to one million Australian dollars also correspond to another uninhabited island, the Herald Islands and McDonald islands. There are also 20 accounts from account holders of Antarctica. If these mistakes are present in a country transparent enough to publish statistics, it’s troubling to think what worse mistakes may be present in much more secretive countries.

In addition, the usual suspects continue to have a big role in holding offshore funds in Australian banks. By calculating an average account balance size (account balance divided by number of accounts), the typical tax havens still top the ranking (without much change from 2018). Account holders from the Marshall islands hold on average $2.9 million in each account, followed by Tuvalu, BVI, Jersey and Cayman Islands. (To put things in perspective, account holders from the US have on average an account balance of $141,000). This was the only possible estimate given that Australia only publishes the number of accounts and their account balance by country, without distinguishing between individuals and corporate account holders, or informing on the annual income of these accounts.

German statistics: the UK, Switzerland and Canada refuse to be included

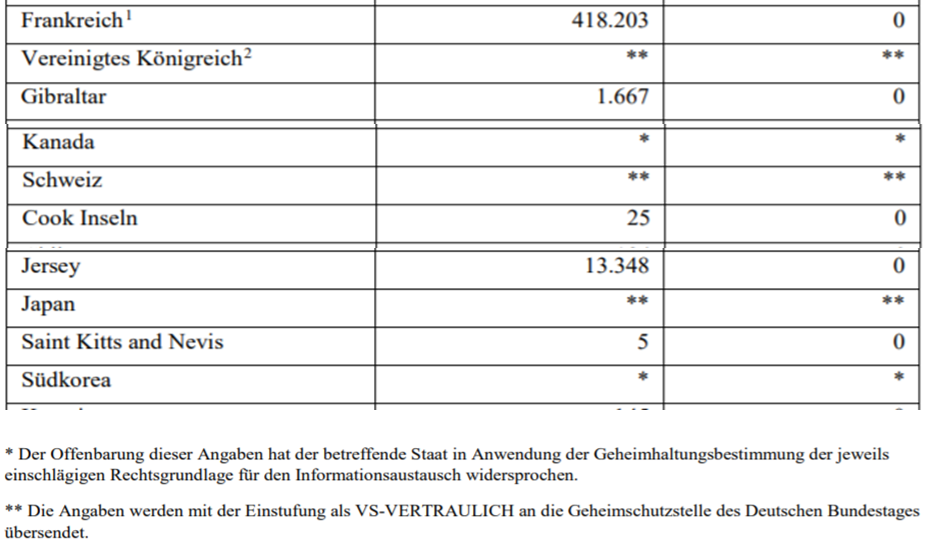

On the bright side, Germany publishes information on accounts held by non-residents in German financial institutions (as Australia does) as well as on German taxpayers’ holdings abroad. It discloses the number of accounts and account balances per country of residence (like Australia) but Germany also discloses the account’s income. However, unlike Australia which publishes information on all 248 jurisdictions, Germany doesn’t publish the details of account holders who are resident in countries excluded from the OECD system. This means that we cannot know how many accounts from “uninhabited” islands have been reported by German banks. This also means that authorities from excluded countries such as Bolivia don’t get even aggregate data on the holdings by Bolivians in German banks. What’s even more troubling is that Germany doesn’t even publish statistics regarding all countries participating in the OECD system. As described by the next extract from the German non-machine readable statistics (it’s a pdf and therefore hard to process by researchers), some secrecy jurisdictions (with an * instead of a value) refuse to have even aggregate statistical data on their residents published by Germany, even though this data belongs to Germany.

We have written about this in our previous blog on Germany’s 2020 statistics (where the same problem happened). In essence, we consider that aggregate statistics should be public because they don’t compromise anyone’s identity (you cannot know that British John Smith has an account in a German bank, let alone how much he has, just by publishing that “Brits have in total $100 M in German banks”). However, Germany asked countries if it was ok to publish statistics and many said no: Switzerland, the UK, Canada, Bermuda, Belgium, Isle of Man, Japan, South Korea. To put this in perspective, even the UAE, Jersey, Cayman Islands or BVI allowed Germany to publish statistics on their residents’ holdings in German banks.

One could argue that information sent to Germany by say Switzerland (about Germans’ holdings in Swiss banks) belongs to Switzerland and that’s why Germany should ask for permission. But information held by German banks in Germany (sent to German authorities by these German banks) should belong to Germany, regardless of whether it refers to German or Swiss or British account holders, so the * that blocks information from some countries (below) is plainly wrong.

Below are some observations of German statistics (after manually processing the data from the pdf they published), considering both accounts held by Germans abroad and accounts held by non-residents in Germany.

a) Highlights of German taxpayers’ foreign holdings

- Since 2018, Germans’ total account balance in Jersey dropped by 98 per cent, from 180 billion Euro to merely 2.9 billion Euro in 2019. One could wonder if this drop is a consequence of the transparency enabled by these statistics and the focus on Jersey by German news articles from last year. It would be good to know where the money went.

- Between 2018 and 2019, Germans’ reported income (eg interest income) in financial institutions in France, the Netherlands and Saudi Arabia jumped exponentially. In France, from 851 million to 114 billion Euro; in the Netherlands from 615 million to 10 billion Euro; and in Saudi Arabia from 2 million to 5.3 billion Euro. It’s worth investigating what kind of business Germans are doing there.

- The top destinations for average account balances (total account balance divided by number of accounts) include the usual secrecy jurisdictions, though the average account balance in Jersey dropped substantially. (The average account balance in Jersey was 14 million Euro in 2018 and dropped to 220,000 Euro in 2019). The 2019 ranking of top destinations for average accounts held by Germans includes: Guernsey (second in 2018), Cayman Islands, Anguilla, Mauritius, Turks and Caicos, St. Lucia, St. Kitts, Monaco, Jersey and BVI.

b) Highlights of non-residents’ holdings in German financial institutions

- Replicating 2018 results, Dutch account holders are making way more money in German banks than any other nationality of account holders. The reported income belonging to Dutch account holders in German financial institutions was 198 billion Euro. The second from the top, Austrian account holders, amounted to just 3.2 billion Euro.

- The average account balance is also similar to 2018 data. The ranking is headed by Jersey account holders (an average account balance of 1.2 million Euro in German banks) followed by Guernsey, Monaco, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Cyprus, Malta, Panama, Andorra and Gibraltar.

Conclusion

Statistics are a crucial transparency tool which should be published by all countries, following the examples of Australia and Germany. They allow authorities from excluded countries to obtain basic data about their residents’ offshore holdings, at least to get them interested in trying to join the system or even to make requests for information. Statistics allow authorities and international organisations to supervise the exchange system, find trends to foster investigations (eg “where did the German money in Jersey banks go to?” or “why are Dutch account holders reporting way more income in German banks than anyone else?”). They also allow civil society organisations and journalists to find red flags and investigate (eg “banks are determining account holders as resident in uninhabited islands”) as well as to hold authorities to account (eg “why are banks still reporting account holders as resident in uninhabited islands for a second time?”).

[Image credit: “Antarctica 2013: Journey to the Crystal Desert” by Christopher.Michel is licensed under CC BY 2.0]

Related articles

One-page policy briefs: ABC policy reforms and human rights in the UN tax convention

The Financial Secrecy Index, a cherished tool for policy research across the globe

Did we really end offshore tax evasion?

The State of Tax Justice 2024

Submission to Special Rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers on undue influence of economic actors on judicial systems

New Tax Justice Network podcast website launched!

Overturning a 100 year legacy: the UN tax vote on the Tax Justice Network podcast, the Taxcast

New Tax Justice Network Data Portal gives unparalleled access to wealth of data on tax havens

SWIFT: The next frontier in countering dirty money