Chris Jones, Yama Temouri, Zheng Cao ■ The finance curse and the ‘Panama’ Papers

When finance gets too big, it can undermine the rest of the economy, and foster corruption in government. That causes significant social harms for a country like the UK. For smaller jurisdictions, where the dominance of finance can be even more intense, the damage of the finance curse can be dramatic. Layered on top of that, smaller jurisdictions are discriminated against in everything from media coverage and political comment on ‘tax havens’, to the listing processes of global North organisations like the OECD and European Union.

The following blog is by Zheng Cao, Chris Jones and Yama Temouri, the authors of a new study that explores the impact of the Panama Papers – a scandal whose very naming focused the reputational damage on one jurisdiction, far in excess of Panama’s real contribution. The authors also show that across jurisdictions, and where no scandal occurs, an over-dominant financial sector is associated with substantial economic harm. How can jurisdictions extricate themselves from the finance curse?

It’s been over 7 years since the release of the Panama Papers by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists: the ‘giant leak of more than 11.5 million financial and legal records [exposing] a system that enabled crime, corruption, and other questionable activity, hidden by secretive offshore companies’. It led to the downfall of Prime Ministers in Iceland and Pakistan as well as exposing the sprawling links and complex connections of wealth held by close Associates of Vladimir Putin. The now infamous Panamanian law firm, Mossack Fonseca, has closed, but the co-founders of the firm are still embroiled in legal issues to this day.

But what impact has the leak had on the economy of Panama? At the time of the scandal, Panama’s President, Juan Carlos Varela, pronounced that the leak addressed tax evasion in general but not Panama per se – hence, deflecting the effects of the scandal on Panama’s image. In a recent study, published in the highly-ranked Journal of Travel Research, we analyse whether the media scandal has had a negative impact on Panama’s economy in terms of its tourism exports, a key sector of the country. Furthermore, we deploy statistical analysis that investigates the long run impact of financial sector growth on the tourism industry.

We relate the impact of the Panama leak to what economists refer to as the natural resource curse, which is well-known in development economics. As a form of Dutch Disease, countries dominated by particular sectors, for instance oil, may crowd out and cause a decline in other areas of the economy, such as manufacturing. Christensen, Shaxson and Wigan apply this concept to the role of the financial sector in the UK and coin the term ‘finance curse’ to describe the situation where an oversized financial system becomes a drag on productivity growth, by driving up prices and nominal exchange rates, harming the competitiveness of the tradeable non-financial sector and taking skilled workers away from high-tech jobs. They also highlight a further effect, that this overdependence leads to the finance sector increasingly dictating policy changes (rather than voters). Over time, this is seen to undermine government accountability and the social contract.

We essentially apply the Dutch disease argument to the impact of offshore finance on tourism. Thus, the financial sector, in particular in tax havens, crowds out the tourism sector. As is well known, tax havens such as the Cayman Islands and the British Virgin Islands are often associated with tourism as well as a dominant offshore financial sector.

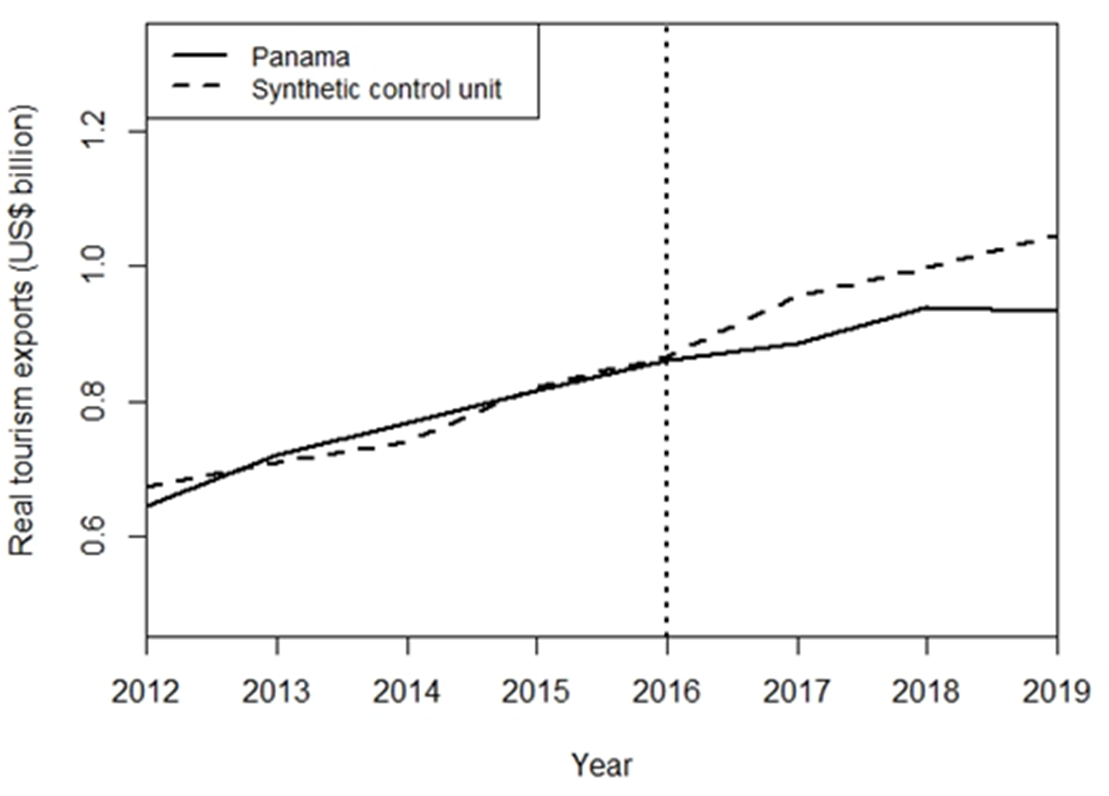

What if there had been no such thing as the Panama Papers? Using a statistical technique called the Synthetic control method, we found that since the scandal in 2016, Panama’s tourism exports have fallen relative to an estimated counterfactual level that would otherwise have been attained. The (synthetic) control unit is made up of a pool of countries that resemble Panama in terms of geography, economic development and dependence on tourism and offshore financial services.

Although tourism exports rose from US$0.85 billion (in real terms; seasonally adjusted) in 2016(Q2) to US$0.94 in 2018(Q1) they would have been considerably higher had the scandal not occurred. This is estimated at 0.8 per cent lower than the control unit for 2016; 7.4 per cent lower for 2017; 5.9 per cent lower for 2018; and 10.7 per cent lower for 2019 (see Figure 1).In summary, we can say that this media scandal appears to have had a significant economic impact, given that tourism contributes around 14.5 per cent to Panama’s GDP.

Figure 1. Growth path of tourism: Panama vs a counterfactual with no ‘Panama Papers’

Note: The solid line shows the actual values of Panama’s real tourism exports, whereas the dashed line represents the counterfactual values of the same in the absence of the scandal.

Our other results uncover more broadly the impact of financial sector development on tourism exports for a sample of small open economies (ie Dutch disease in this context). Our measure for financial development is the value of real financial services exports and we include this in a panel data model with tourism exports as the dependent variable. One of the problems associated with this type of empirical specification is that the underlying process that generates tourism exports may also generate financial services exports. Hence, we estimate a number of models to account for this statistical problem.

We find that a 1 per cent rise in real financial services exports leads to a 0.172 per cent fall in real tourism exports, consistent with the Dutch disease argument.

Our results have a number of important implications. Firstly, it would appear that a major leak and media scandal, such as this, has real economic consequences as well as political consequences. This means that future media investigations that implicate other small open economies may be detrimental in terms of affecting a country’s reputation.

Secondly, our study shows that a tax haven development strategy may be counterproductive. It may crowd out other sectors of a country’s economy. It is well known that the returns of financial sector development typically accrue to the wealthiest members of society and lead to widening inequality. In encouraging greater financial sector development at the expense of higher employment in sectors such as tourism, policy-makers should not be surprised to find that they have created deeper inequality.

Related articles

The “millionaire exodus” visualised

The millionaire exodus myth

10 June 2025

The Financial Secrecy Index, a cherished tool for policy research across the globe

Did we really end offshore tax evasion?

The State of Tax Justice 2024

Submission to EU consultation on Anti-Tax Avoidance Directive (ATAD)

6 November 2024

How “greenlaundering” conceals the full scale of fossil fuel financing

Another EU court case is weaponising human rights against transparency and tax justice

Profit shifting by multinational corporations: Evidence from transaction-level data in Nigeria

5 June 2024