Imagine that the OECD set up a global system of rules for exchanging apples across borders, so that everyone can enjoy apples of different tastes. Apple eaters were delighted. But then someone asked if the apples could be used to make apple juice. “Stop!” the OECD said. “The apples are only authorised for eating, not drinking!”

Fiction? Yes – although if you replace ‘apples’ with ‘information’ then we are back in the real world. Specifically, information that is exchanged between countries under an OECD-led system to stop billionaires, criminals and assorted miscreants from hiding their money in tax havens to escape tax. The problem is, crime-fighters and agencies tackling money laundering or corruption could also use this information that tax authorities are getting access to – but the OECD, in general terms, won’t let this happen.

This situation is ridiculous – and it must change, urgently.

In the OECD’s defense, it’s true that the automatic system was designed to help tax authorities tackle tax issues. But if by serendipity we realise that foreign banking data is also relevant to fighting corruption and money laundering, why not allow this extra use?

The response is that tax authorities cannot share their information, even if they wanted to: information they have is bound by ‘fiscal secrecy’ that cannot be accessed without a court order. That may make sense in relation to disclosing information held by tax authorities to the wider public, but why not share it with other government authorities? The ridiculous underlying assumption here is that all employees of tax agencies are automatically fully honest, compliant with confidentiality and unable to leak or misuse information. Other agencies are full of leakers, crooks and ne’er do wells.

The real reason, is of course, different, and much more political. Information is power. And as we have explained here, governments have very clear incentives. Regardless of politicians’ wonderful speeches and claims about ending illicit financial flows and achieving world peace, tax authorities collect money (tax revenue), while anti-corruption agencies and financial intelligence units can create problems: they may dig into an administration’s dirt (such as the financing of political parties,) and uncover unsavoury friends of the politicians, or the politicians themselves. Drugs money and other ill-gotten funds may be invigorating the real estate market, so (whisper it quietly) unfortunately fighting tax evasion (which increases money for the government) seems to have a higher value for politicians than fighting corruption and money laundering, which may pull money out of real estate and other sectors. In short, we like the (dirty) money.

But beyond the arguments, there are a set of other obstacles to bear in mind.

Legal obstacles

Automatic exchange of banking information based on the OECD’s Common Reporting Standard (CRS) requires countries to have a treaty that allows exchanges of information, and another treaty to establish when, how and what information will actually be exchanged.

The first treaty is the Multilateral

Convention on Administrative Assistance in Tax Matters (the Convention). The

second one, which determines the scope and process to exchange information, is

the famous Multilateral Competent Authority Agreement (MCAA).

The MCAA

has the following obstacles in the recitals preventing the use of information

beyond tax purposes (eg to fight corruption and money laundering):

Whereas, Chapter III of the Convention authorises the exchange of information for tax purposes, including the exchange of information on an automatic basis, and allows the competent authorities of the Jurisdictions to agree the scope and modalities of such automatic exchanges;

Whereas, the Jurisdictions have, or are expected to have, in place by the time the first exchange takes place (i) appropriate safeguards to ensure that the information received pursuant to this Agreement remains confidential and is used solely for the purposes set out in the Convention, and…

…

Section 5. Confidentiality and Data Safeguards

1. All information exchanged is subject to the confidentiality rules and other safeguards provided for in the Convention, including the provisions limiting the use of the information exchanged and,…

(emphasis added)

The Multilateral

Convention on Administrative Assistance in Tax Matters has its problems

too:

Chapter III. Article 4 – General provision

1. The Parties shall exchange any information, in particular as provided in this section, that is foreseeably relevant for the administration or enforcement of their domestic laws concerning the taxes covered by this Convention.

Art. 22 – Secrecy

2. Such information shall in any case be disclosed only to persons or authorities (including courts and administrative or supervisory bodies) concerned with the assessment, collection or recovery of, the enforcement or prosecution in respect of, or the determination of appeals in relation to, taxes of that Party, or the oversight of the above. Only the persons or authorities mentioned above may use the information and then only for such purposes. They may, notwithstanding the provisions of paragraph 1, disclose it in public court proceedings or in judicial decisions relating to such taxes. (emphasis added)

A

light at the end of the tunnel

Not everything is lost. The Convention

(which serves as the legal basis for the MCAA) does open a window in the same restrictive

article 22:

Article 22 – Secrecy

4. Notwithstanding the provisions of paragraphs 1, 2 and 3, information received by a Party may be used for other purposes when such information may be used for such other purposes under the laws of the supplying Party and the competent authority of that Party authorises such use. Information provided by a Party to another Party may be transmitted by the latter to a third Party, subject to prior authorisation by the competent authority of the first-mentioned Party.

In other words, banking information may be

used for other purposes, eg to tackle corruption and money laundering if:

- The country receiving banking

data allows this type of information to be used to tackle corruption and money

laundering under its domestic laws; and

- The country sending information

allows the recipient country to use banking data for this purpose.

Two failed

attempts

The Tax Justice Network had warned about this

loophole on the constraints to use information back in 2014 (see #34). In

2016 together with the Financial

Transparency Coalition we drafted

a declaration (and sent it to the OECD) for all countries to sign. The declaration

proposed that the countries who signed it would allow the banking information

they sent to be used to tackle corruption and money laundering (to tick the

second requirement mentioned above). Unfortunately our draft declaration never

saw the light of day.

We got

our hopes back, in November of 2018 when the OECD’s Global Forum published

the Punta

del Este Declaration, which stated:

4. We encourage all Latin American countries to further strengthen their efforts in tackling cross-border tax evasion, corruption and other financial crimes through closer cooperation, both at the global and regional levels, including in particular through more intense use of all the available exchange of information tools for the purpose of deterring, detecting and prosecuting tax evaders;

(…)

6. We will consider the possibility of (i) wider use of the information provided through exchange of tax information channels for other law enforcement purposes as permitted under the multilateral Convention on Mutual Administrative Assistance in Tax Matters and domestic laws.” (emphasis added)

However, at the March 2019 OECD Integrity

Forum in Paris, the Global Forum explained during a panel that the Punta del Este

declaration was more aspirational than binding, suggesting that it wasn’t

enough to tick the second requirement (the sending country authorising banking

information to be used beyond tax purposes).

The Redundancy Approach

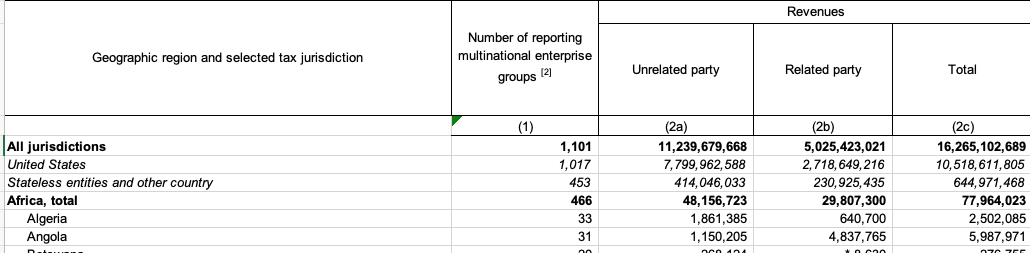

In April 2019, the US Government

Accountability Office (GAO) published the report “Foreign Asset Reporting: Actions Needed to Enhance Compliance Efforts,

Eliminate Overlapping Requirements, and Mitigate Burdens on U.S. Persons Abroad”.

While the focus of the report as described by the title isn’t our biggest

concern, the details mentioned there are very relevant for our discussion. The

report basically describes that the US tax authorities (the IRS) has access to

foreign bank account information based on FATCA (the US equivalent to the

OECD’s CRS for automatic exchange of information), and based on form 8938 filed

by taxpayers. The financial intelligence unit in charge of tackling money

laundering (FinCen) has access to foreign bank account data through the FBAR

form. In other words, both agencies require pretty much the same information

about foreign bank accounts:

Because of overlapping statutory reporting requirements, IRS and FinCEN—both bureaus within Treasury—collect duplicative foreign financial asset data using two different forms (Form 8938 and FBAR)… Table 3 shows that individuals required to report foreign financial assets on Form 8938, in many cases, also must meet FBAR reporting requirements… Table 3 also shows that, in many cases, specified interests in foreign financial assets as defined in Form 8938 instructions are the same as the financial interest in such assets under FBAR. Further, as noted in table 3, the overlapping requirements lead to IRS and FinCEN collecting the same information on certain types of foreign financial assets. For example, both Form 8938 and FBAR collect information on foreign financial accounts for which a person has signature authority and a financial interest in the account. Form 8938 and FBAR also both collect duplicative information on several other types of foreign financial assets, such as foreign mutual funds and accounts at a foreign financial institution that include foreign stock or securities.

The ridiculous part, however, is that (back

to the magic touch of tax authorities), the IRS cannot share information with

the financial intelligence unit without a court order, even though the

financial intelligence unit already has access to similar information (as

described in the extract above):

IRS can share return information with other government agencies and others when it is allowed by statute… However, according to FinCEN officials, FinCEN, law enforcement, and regulators often cannot access information submitted on Forms 8938. While section 6103 provides other exceptions to disclosure prohibitions—such as allowing IRS to share return information with law enforcement agencies for investigation and prosecution of nontax criminal laws—such information is generally only accessible pursuant to a court order.

In other words, one absurd but still useful

approach to counteract the fact that any information held by tax authorities cannot

be shared with other local authorities, is the US redundancy: financial

intelligence units could start asking from taxpayers and why not from foreign

banks, the same banking information that is currently being exchanged among tax

authorities under the OECD’s CRS and FATCA.

Of course we hope the OECD and countries

will become more reasonable, and prevent redundancy and all the compliance

costs, by simply allowing tax authorities to share information with law

enforcement and financial intelligence units, as the GAO report also concluded:

Without congressional action to address overlap in

foreign financial asset reporting requirements, IRS and FinCEN will neither be

able to coordinate efforts to collect and use foreign financial asset

information, nor reduce unnecessary burdens faced by U.S. persons in reporting

duplicative foreign financial asset information.

Conclusion

and next steps

The US case proves that many times different authorities already have access to the same or similar information based on different reporting requirements. This redundancy proves that tax authorities aren’t that special, and that this information isn’t so confidential that it shouldn’t be shared with other authorities, because they already have access to similar type of banking data.

The OECD has reports on cooperation between

tax authorities and financial intelligence units, such as the 2015 report entitled

“Improving

Co-operation Between Tax and Anti-Money Laundering Authorities: access by tax

administrations to information held by financial intelligence units for

criminal and civil purposes”. But as the title suggests, the OECD is more

interested in tax authorities having access to information, not the other way

around.

It’s time for the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) and Egmont Group (network of financial intelligence units) to push to have access to the useful foreign banking data available to tax authorities. This way, they would counter the arguments that suggest that financial intelligence units don’t even want this information because they wouldn’t be able to handle it. But more importantly, it would allow banking data, not only to be used to tackle tax evasion (‘has John declared all the income accrued in this bank account?’) but also to prevent corruption and money laundering (‘how come John has so much money in a bank account, if his declared income is so low?’).

The Convention’s Art. 22.4 proves that the world doesn’t need a new treaty to allow tax authorities to share information with financial intelligence units, but simply to allow these local exchanges in their domestic law and to make sure every other country allows this extra use when they send information abroad. Then it will be up to each country to decide how much and when those local exchanges would take place. At the very least, the OECD, the FATF and the Egmont Group could research and publish details about the countries that are already allowing their tax authorities to share (local) information with other local authorities without a court order.