Andres Knobel ■ Tax justice pushes forward at OECD’s Global Forum

The OECD’s Global Forum held its annual meeting in Uruguay on 22 November 2018 where more of the Tax Justice Network’s proposals and those of our allies on automatic exchange of information have been incorporated into Global Forum policies and remarks – albeit some watering down.

Momentum for tax justice has been steadily growing since the start of the 21st century. The last few years in particular saw significant grounds made following a number of major tax haven leaks. A long list of Tax Justice Network proposals based on the ABC’s of tax transparency – automatic exchange of information, beneficial ownership and country by country reporting – which were brushed off at first as unrealistic – are now endorsed in some form or fashion by most countries and major organisations, including the G20 and the OECD.

As lines in the sand get redrawn, it becomes more urgent than ever to make sure policy changes result in real financial transparency rather than face-saving window dressing. The outcomes of the OECD’s Global Forum have critical implications for the implementation of the automatic exchange of information between countries signed up to the Common Reporting Standard. But do these go far enough to address the asks that the Tax Justice Network is calling for today?

First, the good news.

The OECD calls out the non-reciprocal, American elephant in the room

We repeatedly warned about the US’s lack of participation in the Common Reporting Standard in 2014, 2015, 2016 and especially in our 2018 blog post about how the OECD tax haven blacklist let the US off the hook. Most recently, our bilateral financial secrecy index analyses found that the US was creating the highest risk for offshore tax abuses for the European Union. But now, the Global Forum’s Automatic Exchange Implementation Report surprised us with this mild, but still relevant statement:

8. All jurisdictions asked to commit to the Global Forum’s AEOI Standard have now done so, except the United States. As of 2015, the United States exchanges certain information automatically pursuant to its various Model 1 FATCA intergovernmental agreements, which includes recognition by the government of the United States of the need to achieve full reciprocity.” (emphasis added)

This is relevant because it’s the first time that the OECD states the obvious: that the US isn’t implementing the Common Reporting Standard and that the US exchanges only “certain” information automatically. The OECD’s list of jurisdictions committed to the Common Reporting Standard only has a footnote saying that “the US exchanges information automatically pursuant to FATCA” (without saying that this means the US is not implementing the Common Reporting Standard). In the past, Switzerland and Luxembourg tried to treat the US as participating in the Common Reporting Standard in order to disregard anti-avoidance measures applicable to non-participating countries. This new statement from the Global Forum helps narrow the grey area the US has operated in.

Curtain call for the automatic exchange of information dating game

The Tax Justice Network has insisted the automatic exchange of information between countries can only bring about real transparency when all countries automatically exchange information with each other. But the OECD’s legal framework for automatic exchange of information effectively created a dating game where countries can cherry-pick who they share information with. For a good example of this, see our blog on Switzerland’s approach to automatic exchange of information.

The Global Forum has now called on members to share information with all participating countries, putting an end to the dating game:

7. All Global Forum members (…) were asked to commit to: (…) 2. exchange information with all interested appropriate partners – being all those interested in receiving information and that meet the standards in relation to confidentiality and the proper use of data.” (emphasis added)

More, though not enough, light on which countries are choosing financial secrecy

Up until now, we were unable to determine which countries were choosing “voluntary secrecy”, that is, to send but not receive any information via the automatic exchange of information. Through voluntary secrecy, tax havens can effectively offer a way out of the increasingly global system of automatic exchange of information by selling passports or residencies. Passports and residencies for sale schemes, aka “golden visas”, from voluntary secrecy countries create a huge risk because anyone acquiring them (and claiming to be a resident from these voluntary secrecy countries) would become a non-reportable person, meaning that banks wouldn’t even bother to collect any information about them.

The OECD had previously omitted to name which countries were choosing voluntary secrecy. The OECD merely listed all countries sending and receiving information, mixing together those that were not receiving information because they lacked the technical or legal requirements with those that were not receiving information because they voluntarily chose not to. The Global Forum is now naming some names:

As an example, some jurisdictions do not wish to receive information. This includes 11 jurisdictions that do not have systems for direct taxation and exchange information only on a non-reciprocal basis (i.e. they send but do not receive information)1

1 Anguilla, The Bahamas, Bahrain, Bermuda, British Virgin Islands, Cayman Islands, Marshall Islands, Nauru, Qatar, Turks and Caicos Islands and United Arab Emirates”

It appears that out of all the countries choosing voluntary secrecy, the above listed 11 countries do not receive information because they do not have systems in place for direct taxation. Additionally, Switzerland has confirmed that both Cyprus and Romania do not receive information because they do not yet meet international requirements on confidentiality and data security. What reasons, then, do the other countries choosing voluntary secrecy, like Costa Rica, have for not receiving information? Why is the refusal to receive information that can be used to tackle tax abuse, corruption and money laundering accepted as a valid choice?

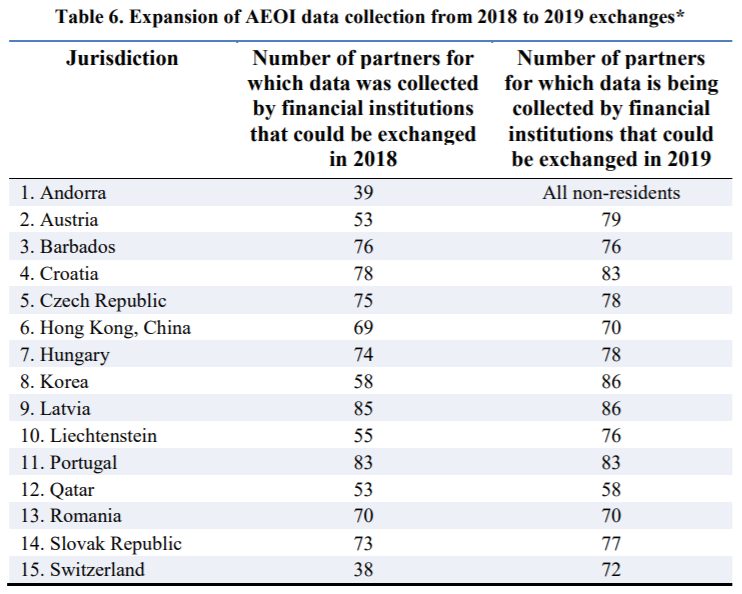

The risk of voluntary secrecy is also relevant for the statistics on automatic exchange of information that we have been proposing since 2014 in different publications and interactions with policy makers (see the last point below). The idea of these statistics is to show how much money residents from every country hold in each financial centre. Our proposed statistics would be highly hampered if countries failed to collect information on residents of certain countries in the first place, especially on those claiming to be resident in a voluntary secrecy tax haven. In such cases, statistics would be able to show how much money Argentine residents hold in say Switzerland, but not how much money Cayman or Anguilla residents hold in Swiss banks. This would create a big black hole, reducing the effectiveness of statistics. So far it appears that only Andorra will address this properly by collecting information on all non-residents (the famous “wider approach”). Others, particularly Switzerland, Hong Kong and Qatar appear to be coordinating with the voluntary secrecy tax havens or with secrecy in general, since they will collect information on much fewer residents than other countries:

Using exchanged information to tackle corruption and money laundering

Since 2014, the Tax Justice Network has repeatedly made the case that information received through the automatic exchange of information under the Common Reporting Standard can help tackle not just tax evasion, but also corruption and money laundering. However, the OECD (very likely pushed by Switzerland’s “speciality” principle) wouldn’t allow authorities to use information for these “extra” non-tax purposes.

In order to address this, back in 2016 we joined the Financial Transparency Coalition in a letter to the OECD and the Global Forum, asking them to address this issue. We even drafted a declaration, based on the Multilateral Tax Convention requirements, which all countries could sign to allow for information to be used to tackle corruption and money laundering. We received no response. But now, in Uruguay, the Global Forum published the Punta del Este Declaration signed by Latin American ministers stating:

4. We encourage all Latin American countries to further strengthen their efforts in tackling cross-border tax evasion, corruption and other financial crimes through closer cooperation, both at the global and regional levels, including in particular through more intense use of all the available exchange of information tools for the purpose of deterring, detecting and prosecuting tax evaders;

(…)

6. We will consider the possibility of (i) wider use of the information provided through exchange of tax information channels for other law enforcement purposes as permitted under the multilateral Convention on Mutual Administrative Assistance in Tax Matters and domestic laws.” (emphasis added)

The Global Forum’s recognition here of the key role exchange of information plays in tackling wider corruption, crime and violence is paramount. Importantly, the Punta del Este Declaration breaks rank with the eyes wide shut consensus, although other countries within and outside Latin America should join the Declaration and start using information to tackle all illicit financial flows.

The impact of the all these tax justice successes at the Global Forum will go a long way in the near and far future. Some Tax Justice Network asks, however, were not addressed by the OECD or the Global Forum. Here’s the bad news.

The OECD sees the risks of golden visas, but not the risktakers

Since the OECD published the Common Reporting Standard (CRS) in 2014, the Tax Justice Network has warned that passports and residency for sale schemes can be abused to avoid automatic exchanges of information. The OECD finally addressed the risk in February 2018 when they opened a consultation on this issue. This consultation led us to write a report on risky jurisdictions offering golden visas and we joined the Financial Transparency Coalition’s response to the OECD consultation.

On 16 October 2018, the OECD eventually came up with a list of 21 risky jurisdictions whose golden visas schemes potentially jeopardised the integrity of the Common Reporting Standard. On November 13 2018, we published a blog post criticizing the OECD’s blacklist for not just being unproductively short, but for also failing to include OECD countries and for having a knack for getting even shorter (four jurisdictions had already been removed between 16 October and 13 November). Just over a week later, the OECD’s Global Forum decided to remove yet another jurisdiction for the list, this time Panama.

The OECD drag their feet on making automatically exchanged information publicly available

Based on our research on the loopholes affecting the effectiveness of automatic exchange of information, we have concluded that the best approach to address these loopholes is to publish aggregate statistics on the data collected for the automatic exchange of information under the Common Reporting Standard. These statistics would breach no confidentiality and demand no extra cost from tax authorities or banks. They have already collected all relevant information. All we are asking is for tax authorities to publish the totals by country of origins, eg “In Germany, all Argentine residents hold X million euros, all Austrian residents hold Y million euros, all Brazilian residents hold Z million euros.” We have created a template for this here, we have explained how it could be used to identify schemes that avoid being reported under automatic exchange of information here, and we have given an example of similar financial data that’s already public here.

Now, we are waiting for the OECD to come up themselves with the idea of publicising statistics to ensure compliance with the Common Reporting Standard. Importantly, statistics would also give civil society organisations, journalists and authorities from developing countries that are unable to join the Common Reporting Standard access to basic aggregate information about where the world’s residents hold their offshore accounts.

The march of tax justice has proved to be irrevocable. As the year draws to a close, the progress achieved in 2018, on top of that achieved in 2017, is worth taking a moment to celebrate. And while a lot of work still lies ahead, we at The Tax Justice Network are very excited about taking the momentum for tax justice to greater heights in the year to come.

Related articles

2025: The year tax justice became part of the world’s problem-solving infrastructure

One-page policy briefs: ABC policy reforms and human rights in the UN tax convention

The Financial Secrecy Index, a cherished tool for policy research across the globe

Did we really end offshore tax evasion?

The State of Tax Justice 2024

Submission to Special Rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers on undue influence of economic actors on judicial systems

New Tax Justice Network podcast website launched!

Overturning a 100 year legacy: the UN tax vote on the Tax Justice Network podcast, the Taxcast

New Tax Justice Network Data Portal gives unparalleled access to wealth of data on tax havens