Australia has become the first country to publish statistics on automatic exchange of information for all jurisdictions, especially those that cannot join the automatic exchange system. Here’s what they reveal and why it has more potential than statistics published by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS).

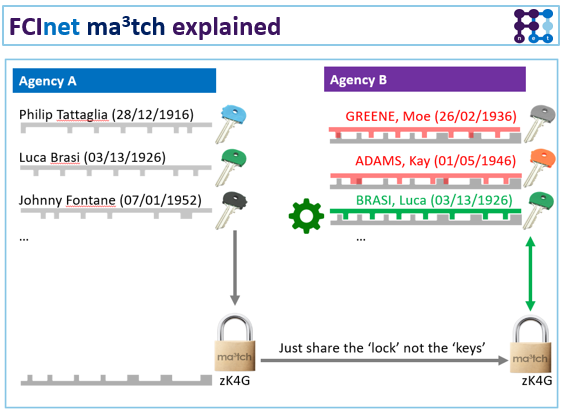

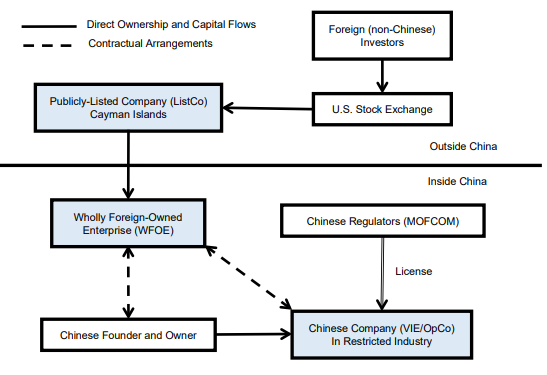

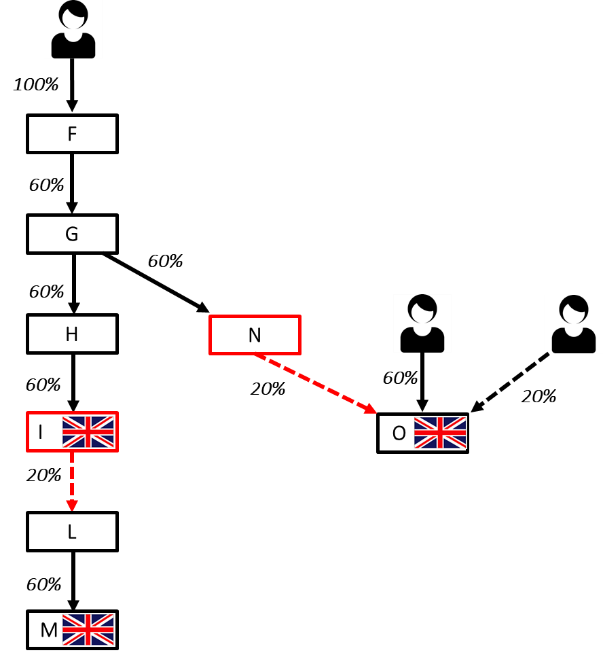

We’ve been advocating for automatic exchange of bank account information for years, in the hope that all countries, especially lower-income ones, would reap the benefits. Unfortunately, when the OECD published its Common Reporting Standard (CRS) for automatic exchange of bank account information, they added a very problematic feature. They require reciprocity from countries willing to receive information. This automatically excludes most lower-income developing countries as most of them are unable to collect and share information held in their financial institutions because of a lack of resources or infrastructure.

Of course, in the long run all countries should be able to collect and share information with others. Otherwise they risk becoming a tax haven or secrecy jurisdiction. However, in the short term, all countries should be able to receive information about their elite’s holdings in financial centres.

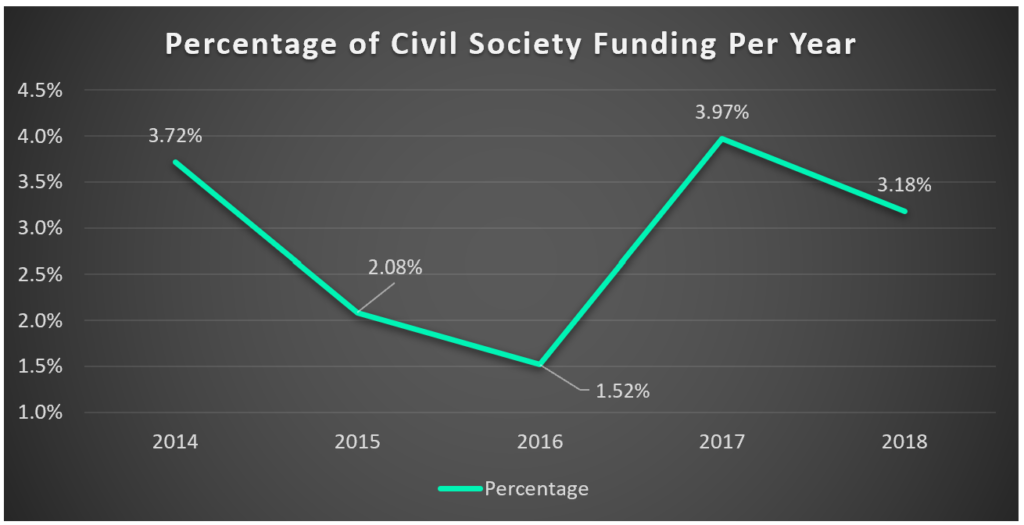

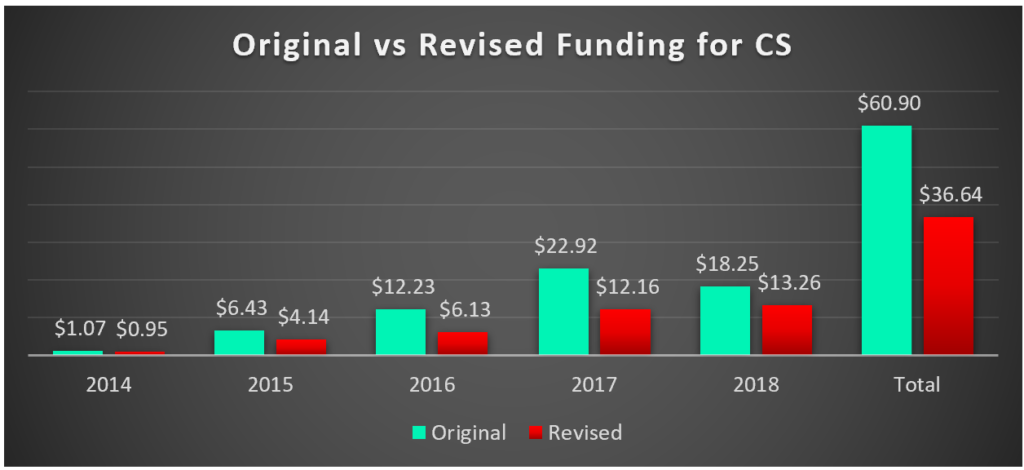

Thanks to the great work of Mark Zirnsak from Tax Justice Network-Australia, Australia passed a legal amendment back in 2016 requiring it to publish basic statistics (we’ve been asking for comprehensive statistics and have even designed a template, see page 37), but hey, this is a good start.

Unfortunately, Australia only started exchanges in 2018 and the law there requires statistics to begin from that year only. The Financial Secrecy Index assesses, under indicator 16, whether countries are publishing statistics on automatic exchange and it acknowledges Australia’s law. However, Australia didn’t get any transparency credit in the latest edition of the Index because no statistics had yet been published by the cut-off date.

However, Australia has finally published its basic statistics!

First, let’s look at the shortcomings/things for improvement (so as to end on a positive note):

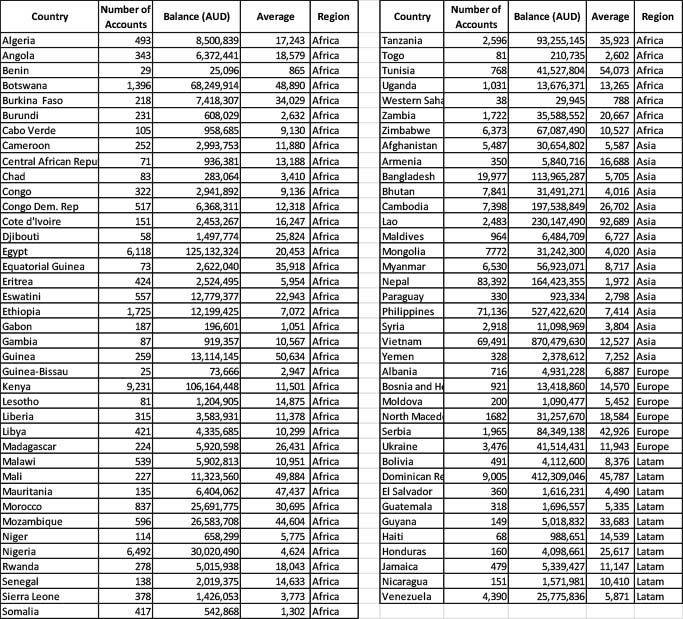

- Information was published as an image, so we had to use an OCR software (Optical Character Recognition) plus manual checks to extract the numbers from the image and convert it into an Excel document to do our analysis.

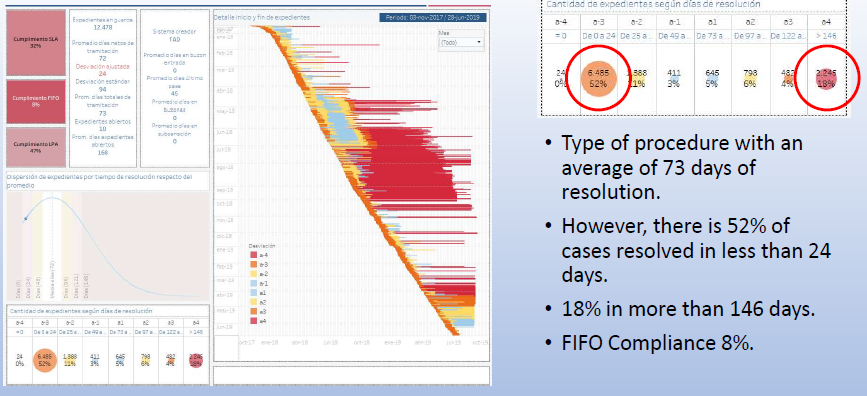

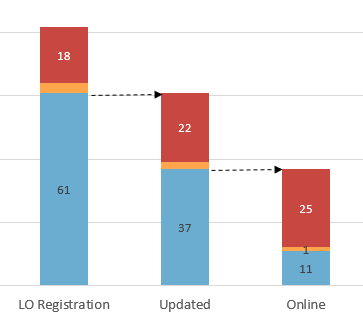

- There isn’t much analysis to do because Australia has only published the total number of accounts and the total balance account as of 31 December 2018. We have no idea whether these are accounts held by entities (eg companies, trusts) or by individuals. We also don’t know how accounts evolved since people became generally aware of automatic exchange of information. For that we would need to see the values for accounts since 2013, before the Common Reporting Standard had been published, ie before anyone had any reason to rearrange their affairs in order to avoid scrutiny.

- There is no information on income or on the type of financial institutions that hold these accounts (is this money held in depository banks, or is it held in custodial banks or in investment entities?).

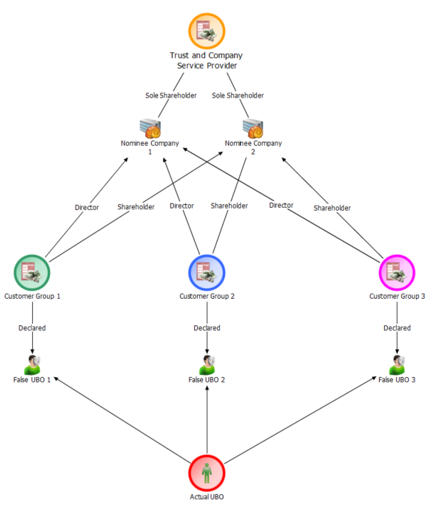

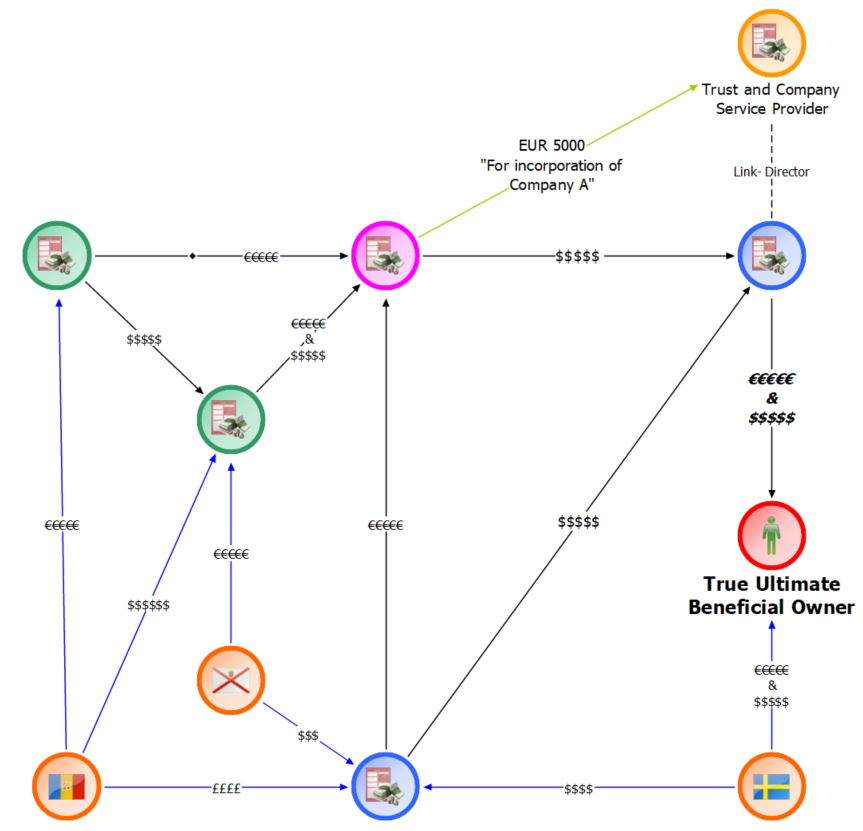

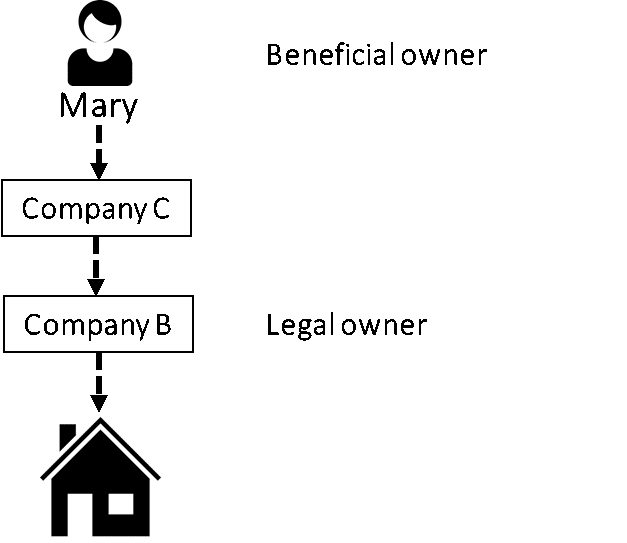

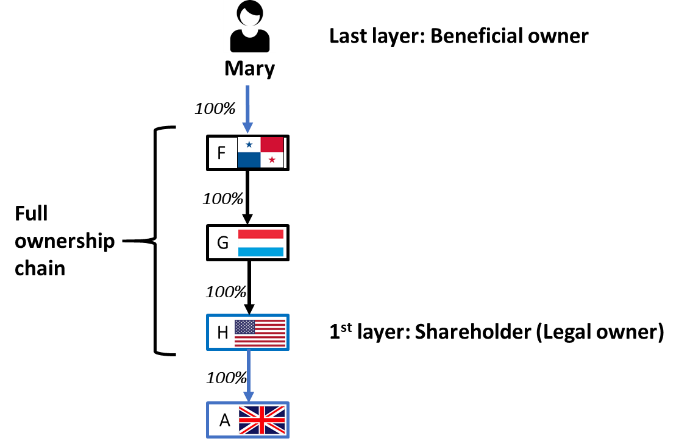

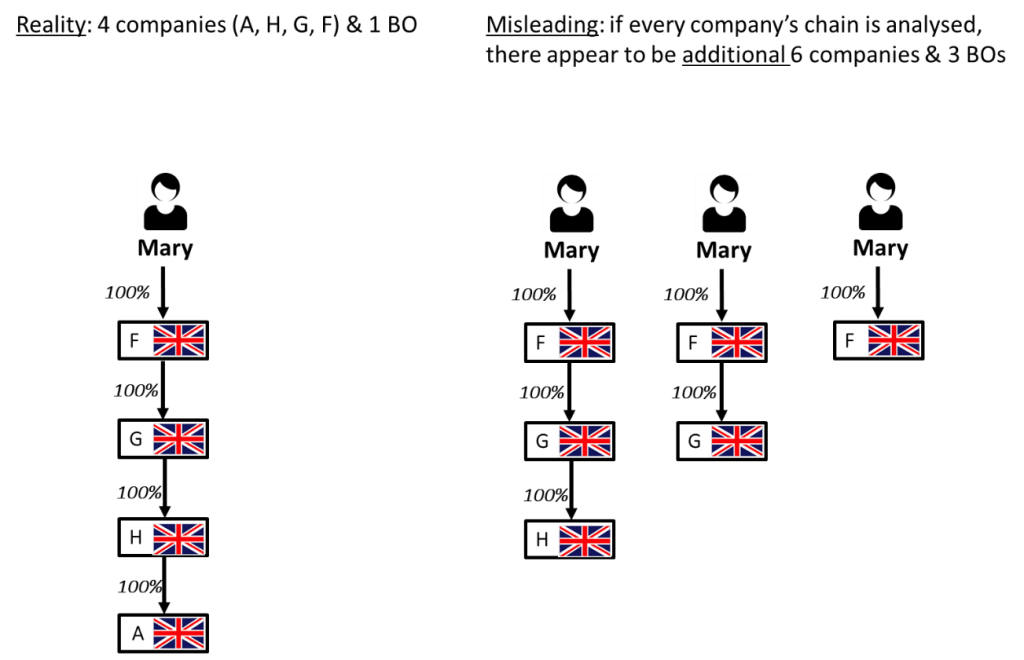

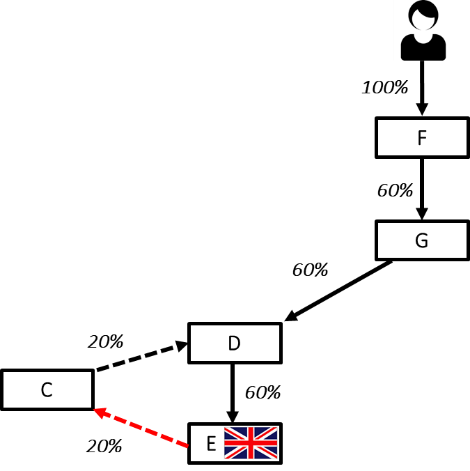

- We don’t know anything about the beneficial owners of the Australian accounts, for cases where account holders are entities such as companies or trusts.

Now, the positives:

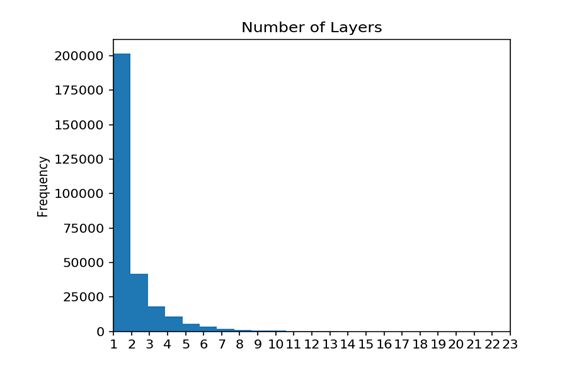

- Australia has published information on absolutely all countries. In total, there’s data on the accounts held in Australian financial institutions by residents from 248 different jurisdictions, while only 100 of them participate in the Common Reporting Standard.

On the one hand, Australia will be recognised in the next edition of the Financial Secrecy Index not only under indicator 16 for their publishing statistics, but also under indicator 18 because these statistics reveal that Australia is applying the so-called ‘wider-wider approach’: information on all account holders (not only those who are resident in a participating country) was not only collected by Australian financial institutions but also reported to Australian authorities (We were only previously aware of Argentina, Estonia and Ireland applying this approach).

These statistics, covering all jurisdictions, is exactly what we were asking for. Thanks to Australia’s statistics, the 148 jurisdictions unable to join the automatic exchange system will at least find out how much reportable money their taxpayers hold in Australian financial institutions. Of these 148, those lucky enough to have an exchange of information agreement with Australia can make a request for information, or even better, Australia could share it with them spontaneously (or at least share more details than what they have published, if not the full details on each account holder). Local civil society organisations or journalists could also start investigations and push their countries to obtain information from Australia.

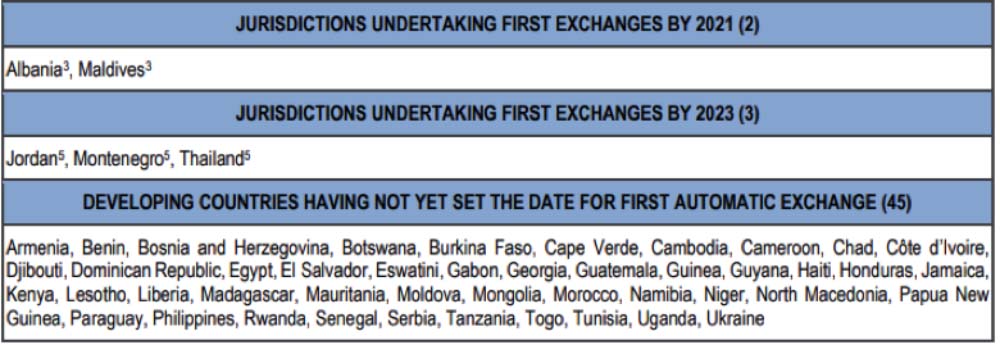

There are many countries that haven’t been able to join the automatic exchange system yet, according to the OECD:

Australia published information on all of them and beyond:

Findings

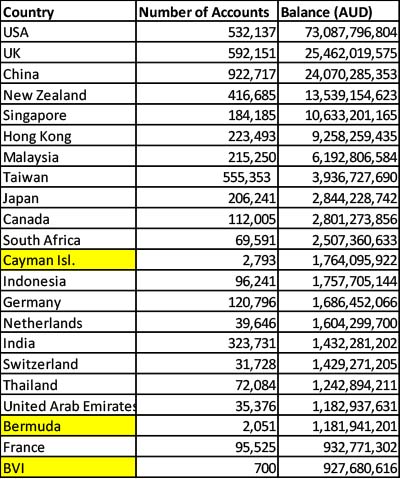

- In 2018, residents from 248 jurisdictions held 6.1 million accounts in Australian financial institutions with a total account balance of AUD 208 billion.

- Looking at the countries with the highest number of accounts, results look as expected, given the size and geographical closeness of countries to Australia:

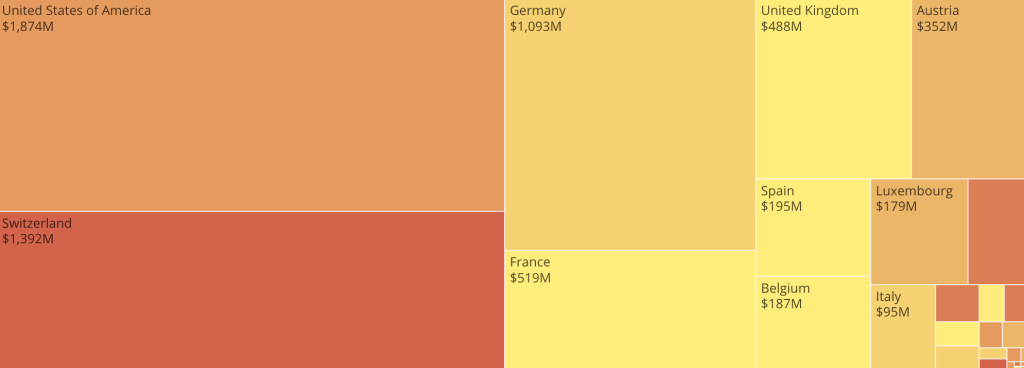

- When looking at the jurisdictions with the highest account balance, some tax havens or secrecy jurisdictions start to appear:

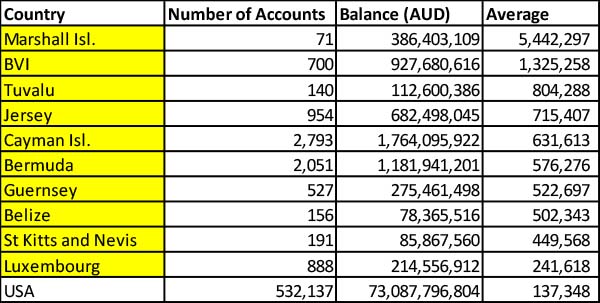

- When looking at the highest average account balance, tax havens and secrecy jurisdictions take over:

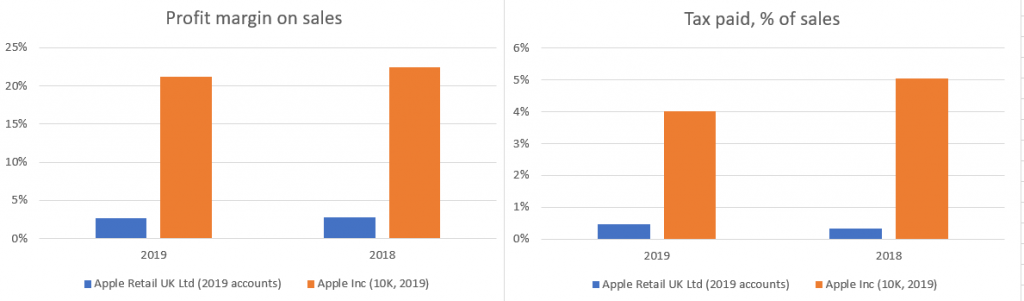

Unfortunately, as we’ve said, we don’t know which of these accounts correspond to individuals and which to entities such as companies or trusts. It would be unlikely for so many individuals from the Cayman Islands to have that many accounts in Australia, unless these refer to individuals who acquired golden visas. If these refer to entities, Australia could publish information about the residence of the beneficial owners of those entities so that countries could become aware of their individual taxpayers’ holdings in Australia, but also the preferred jurisdiction by those beneficial owners to incorporate shell companies (to hold bank accounts). Speaking of beneficial ownership, while Australia is a great leader in publishing statistics on automatic exchange of information, it’s lagging behind on legal and beneficial ownership transparency. While more than 80 jurisdictions already have laws requiring beneficial owners of companies and other legal vehicles to register with government authorities, Australia doesn’t even ensure updated legal ownership information is registered.

What next?

- Consistency with the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) and other macro data

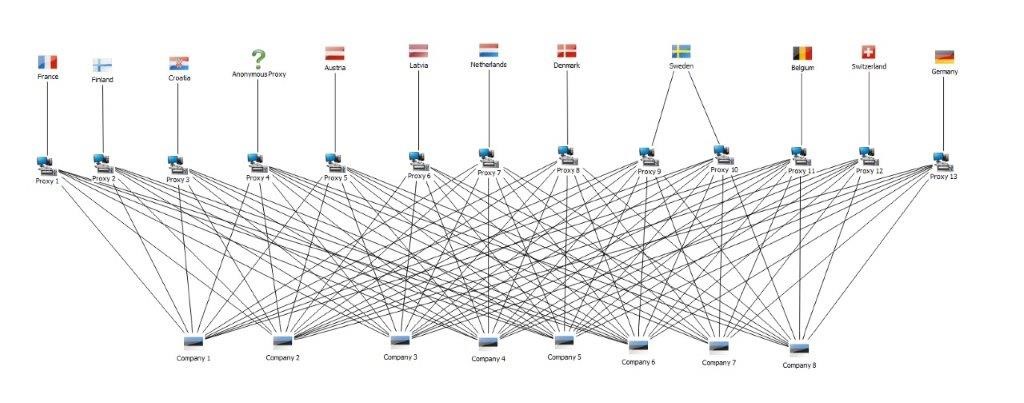

While the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) has been publishing data on deposits by country of origin, this data has shortcomings for determining the possible revenue loss for a country. It includes mostly loans and deposits in depository institutions. Some Central Banks, eg in the US or Switzerland, publish similar data, with similar constraints. Meanwhile, the automatic exchange system already covers information based on the tax residence of account holders both at the legal owner and beneficial owner level. It also covers financial assets held by custodial institutions, investment entities and insurance companies. More importantly, other than information on account balance (deposits as for 31 December), the automatic exchange system also covers income related to each account. This makes it more directly relevant for taxation.

However, the Bank for International Settlements data may be relevant for cross-checks and to detect loopholes. If Australia, and other countries publishing statistics on automatic exchange, disaggregated information for the type of reporting financial institution (eg depository institutions) and the Bank for International Settlements described in its statistics what information refers exclusively to deposits (not loans) in depository institutions, we could then cross-check both reports for consistency. These statistics could reveal loopholes affecting the automatic exchange system, given that some types of accounts and some types of account holders are considered non-reportable. Even without further disaggregation of the Bank for International Settlements data, consistency analyses could be carried out once multi-year (panel) data or data for multiple countries (cross-sectional) was available both for the Common Reporting Standard and the Bank for International Settlements statistics.

- Lower-income countries joining the multilateral tax convention and the automatic exchange system

While ideally all countries should be able to join the automatic exchange system, the first step is to have an international agreement to allow exchanges. Having an applicable exchange agreement with the relevant financial centre, eg Australia, allows a country to make a request for information and to receive a spontaneous exchange, until the time in which they may join the automatic exchange system.

For example, one of the non-participating countries with the highest value held in Australian financial institutions is the Philippines, with a total of AUD 527 million in 2018. The Philippines hasn’t committed to joining the automatic exchange system yet, and while they have signed the Convention on Mutual Administrative Assistance in Tax Matters (the multilateral tax convention), they haven’t ratified it yet, so it’s not in force. Nevertheless, there is a double tax agreement between Australia and the Philippines in place, so Australia should be able to share information spontaneously, or the Philippines should be able to make a “group request”.

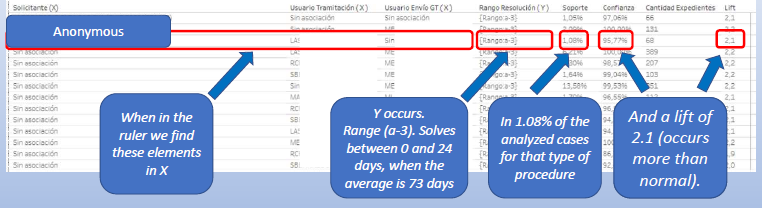

The “group request” does not need to identify any specific taxpayer, but it needs more details than a mere suspicion to be considered foreseeably relevant and not a fishing expedition. The OECD gives an example of what an acceptable group request would look like:

8. h) Financial service provider B is established in State B. The tax authorities of State A have discovered that B is marketing a financial product to State A residents using misleading information suggesting that the product eliminates the State A income tax liability on the income accumulated within the product. The product requires that an account be opened with B through which the investment is made. State A’s tax authorities have issued a taxpayer alert, warning all taxpayers about the product and clarifying that it does not achieve the suggested tax effect and that income generated by the product must be reported. Nevertheless, B continues to market the product on its website, and State A has evidence that it also markets the product through a network of advisors. State A has already discovered several resident taxpayers that have invested in the product, all of whom had failed to report the income generated by their investments. State A has exhausted its domestic means of obtaining information on the identity of its residents that have invested in the product. State A requests information from the competent authority of State B on all State A residents that (i) have an account with B and (ii) have invested in the financial product. In the request, State A provides the above information, including details of the financial product and the status of its investigation.

While a group request would have to be tested, it’s unlikely that the double tax agreement between Australia and the Philippines, signed in 1980, would allow group requests given that it is not explicitly allowed. If group requests were allowed, based on the OECD example, Australia might respond to the request if the Philippines could prove that investments in Australia are popular/advertised among its residents and that none (or very little) of the AUD 527 million held by residents in Australian banks has been reported to the Philippines’ tax authorities. In the absence of routine reporting, the omission of income is likely the norm. Assuming that only 10 per cent of the AUD 527 million are declared by Philippines taxpayers, and assuming a 5 per cent return on investment, it would result in an additional taxable revenue in the Philippines of AUD 23.7 million (= 5% x 90% of 527 million) per annum for Australian income alone. With the Philippines personal income tax rate of 20 per cent for passive income, that would amount to about AUD 5 million of additional revenue.

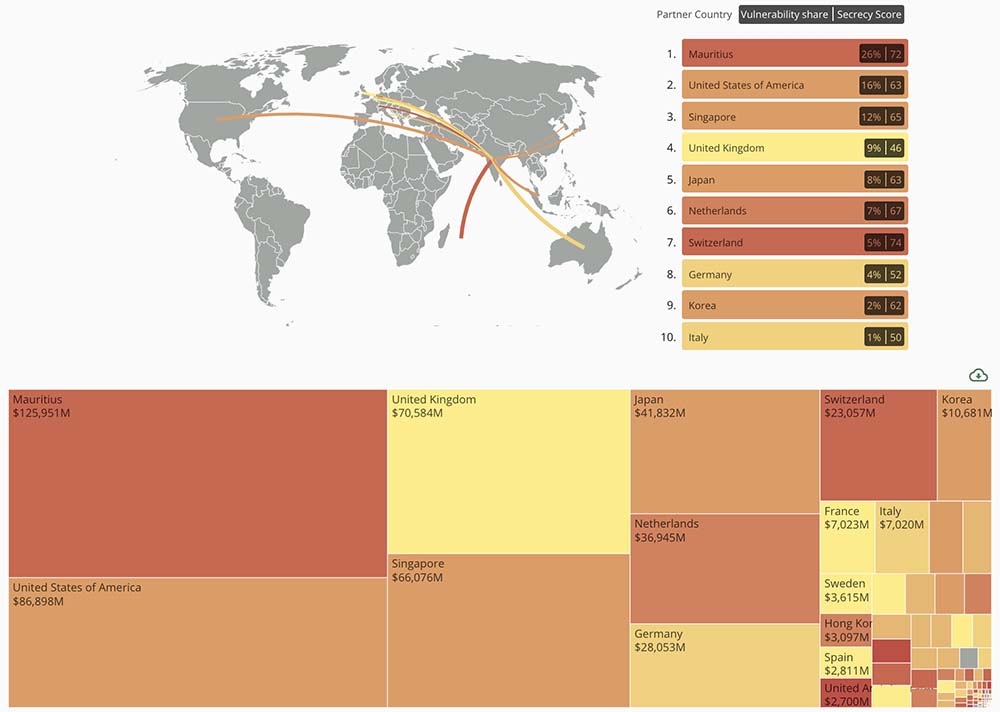

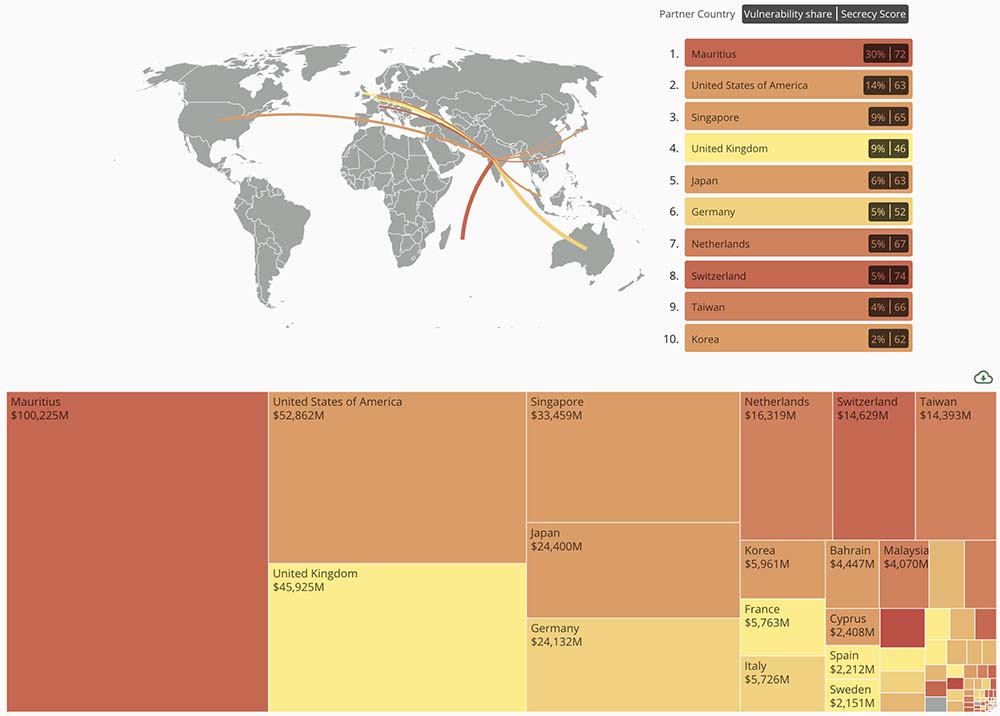

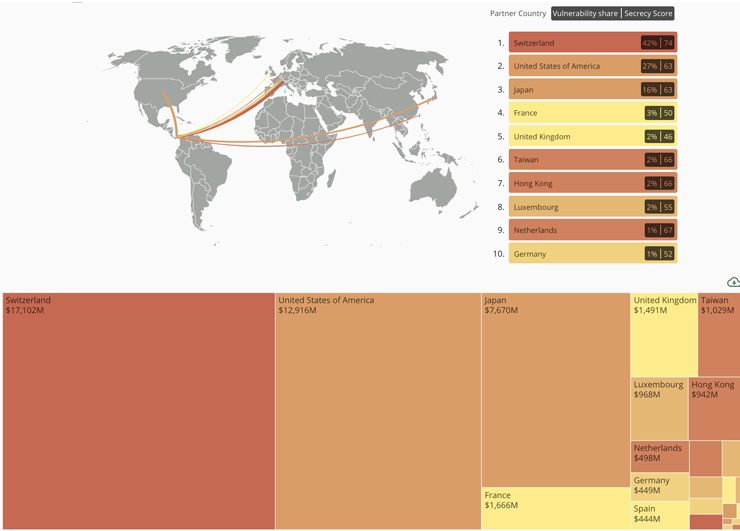

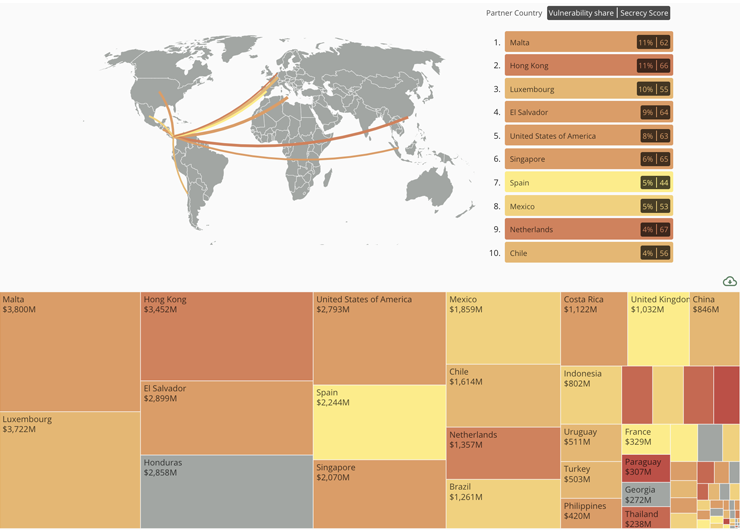

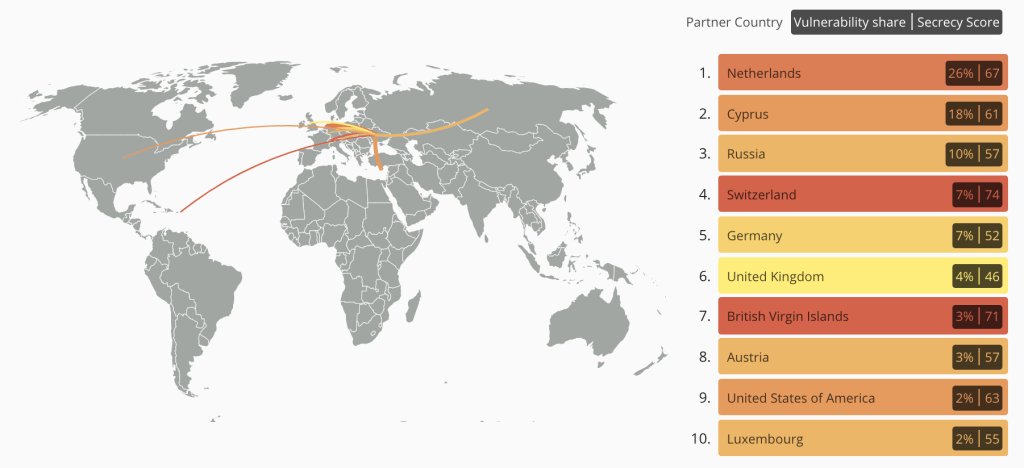

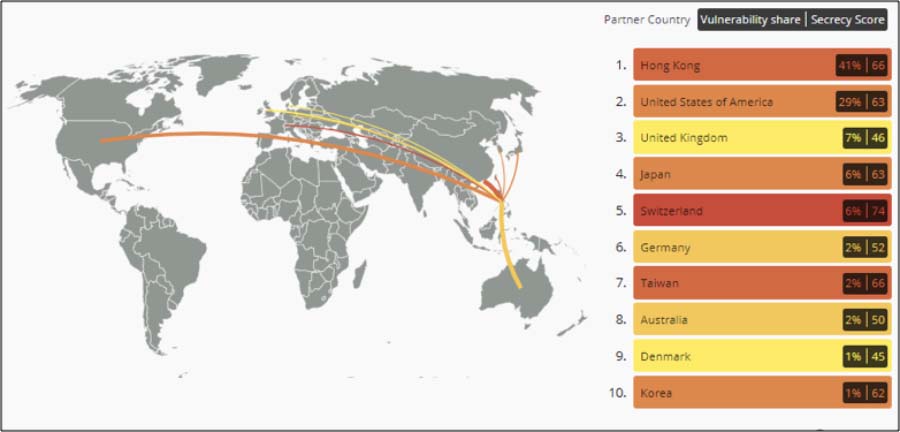

Ideally, these statistics should prompt lower income countries to sign the multilateral tax convention, make requests for information and join the automatic exchange system. In terms of priority countries, this will for now depend on the countries actually publishing statistics, but once more options are available countries could use the Tax Justice Network’s Illicit Financial Flows Vulnerability Tracker. In the case of the Philippines, Australia is ranked 8th:

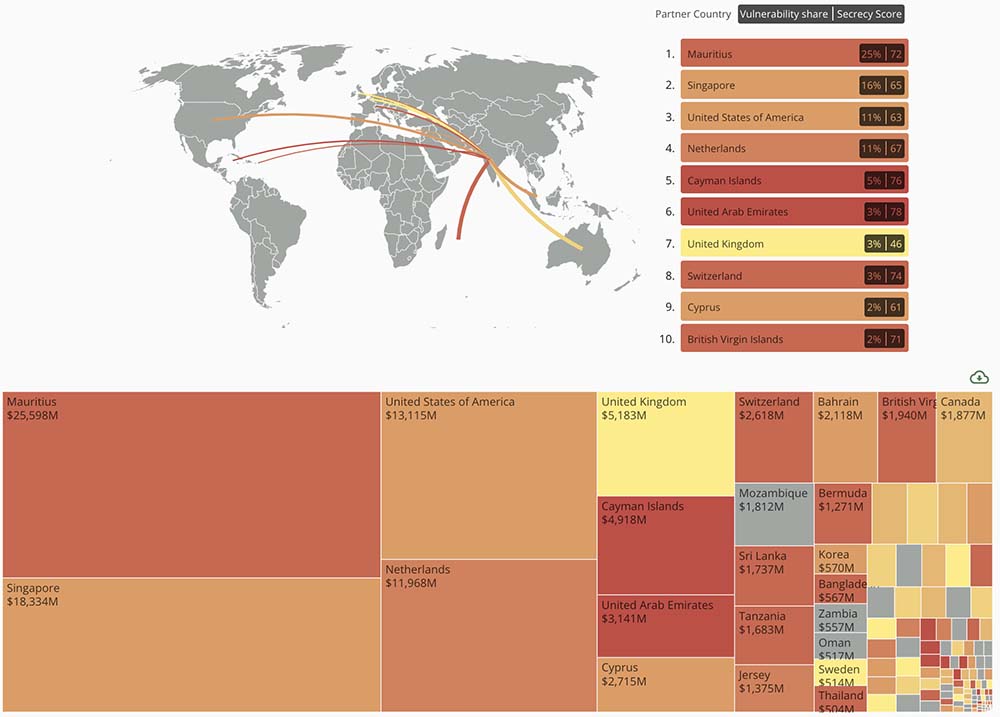

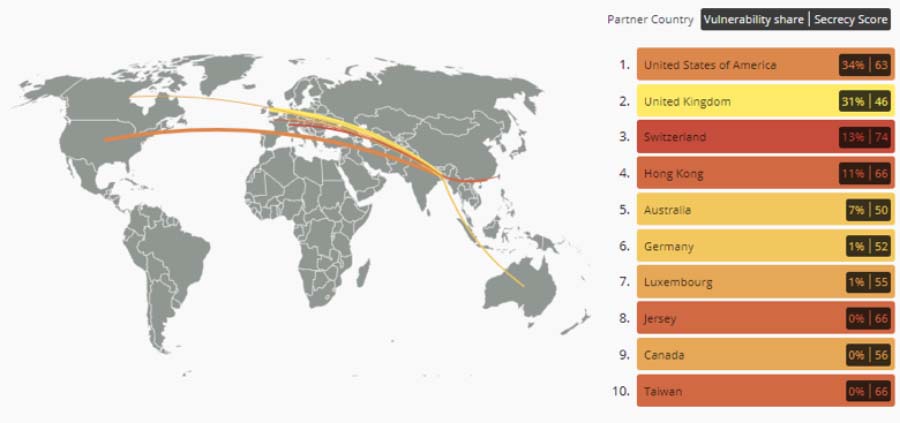

Other countries are in worse conditions than the Philippines because they are neither participants in the automatic exchanges nor do they have any relevant agreement to obtain information from Australia. One such example is Bangladesh, for which Australia represents the 5th riskiest country in terms of vulnerability of bank deposits (based on the data from the Bank for International Settlements). Based on Australia’s statistics on automatic exchange of information, residents from Bangladesh have AUD 113 million in Australian financial institutions. Based on the same assumptions as above on return on investment and undeclared assets abroad, Bangladesh could raise an additional AUD 1.5 million of tax revenue per annum from Australia (based on a highest statutory personal income tax rate on financial investment of 30 per cent), through joining the Common Reporting Standard or otherwise obtaining the relevant tax data from Australia.

As for other regions such as Latin America and Africa, other countries that are unable to automatically obtain information from Australia, but that could still make a request for information, include the Dominican Republic, whose residents have AUD 412 million in Australian banks, and Kenya, whose residents have AUD 106 million.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this a great first step, and hopefully many lower-income countries will now start asking Australia for more details on their residents’ holdings in Australian financial institutions (or first signing relevant conventions). We need more countries to publish these statistics and with a higher level of detail so we and others can start measuring and understanding offshore holdings, and different avoidance or secrecy schemes.

Photo courtesy of: Liam Pozz/Unsplash