Andres Knobel ■ Is financial secrecy always bad?

The Tax Justice Network has long been an opponent of financial secrecy. Wealthy oligarchs, criminals, and looters have increasingly been paying lawyers, accountants and bankers to set up secrecy vehicles such as trusts, foundations and shell companies to hide their ownership of all sorts of assets from the forces of law and order, from our tax authorities, and from the societies in which they live.

This creates one rule for the wealthy and powerful (who can afford to pay those lawyers, accountants and bankers) and another set of rules for everyone else. The result is more crime, worsening inequality, weaker accountability, greater corruption, more looting and illicit financial flows, plummeting tax revenues, and so on. The use of secrecy vehicles as “strategic corruption” undermines democratic societies and threatens national security in country after country.

The defenders of financial secrecy make a range of tired and mostly bogus arguments to justify all this: we look at and demolish their main arguments one by one, here.

However, is secrecy (or privacy, as our opponents prefer to call it) always bad? If you go to the doctor with embarrassing ailments, would it be acceptable for your doctor to nail a list of all your medical problems to their front door (or, worse, on the internet), free for anyone to view? Of course not! There is, as with most important things in life, a balance to be struck. The question is, where?

Looking for the contours of acceptable secrecy

The scholar Amnon Lehavi has published a paper entitled “Property and Secrecy,” laying out a useful description of the scope of privacy arguments. It touches on many topics dear to us, including trusts, beneficial ownership and listed companies.

The paper focuses significantly on what might be called internal stakeholders: for example, minority versus majority shareholders, or neighbours within a building or area. The Tax Justice Network, on the contrary, usually focuses on external stakeholders, those who are not invited to the negotiating table, especially the wider public and societies which might be damaged by the actions of individuals, entities or other secretive arrangements.

Legal ownership: having your cake and eating it

Those who oppose transparency reforms that we and our allies advocate – such as public beneficial ownership registries – often invoke rights to privacy. Alternatively they use “efficiency” arguments and speak of “liberty” with a broad ideological opposition to regulation and “red tape” which they claim are hindering business and development. Markets should regulate themselves, many (lazily) argue. We know that they just don’t.

At the same time though, these opponents of “Big Government” do demand that a big and powerful government comes to their aid when it comes to defending their private property through court systems and the passing of private interest-friendly legislation.

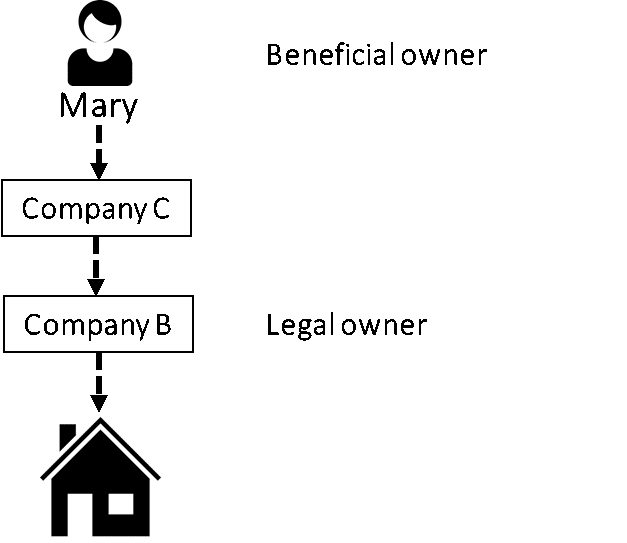

But how can the private property of owners be protected, if those owners are to be kept secret? The answer, called “legal ownership”, is based on disclosing only a mask while obscuring the real owners (called the “beneficial owners”).

Here’s a conversation that exemplifies what may happen.

Legal representative of company A: “The State confirms that this house belongs to company A, so get out!”

Person inside the house: “But who are you? Who is company A? Who is behind it?”

Legal representative of company A: “That’s (legally) none of your business!”

By owning any asset, eg a house, through an entity, trustee or nominee, it’s possible to register only the entity as the (legal) owner and thus benefit from property rights and secrecy (because the real (beneficial) owner is not disclosed). However, it is still essential that the authorities know who the beneficial owners are: for example, to know whether the person is paying the right wealth or income tax, or to find out how they afforded to buy the property, to make sure it’s not through the proceeds of corruption or part of a money laundering scheme.

In our view, transparency isn’t a favour that owners graciously agree to grant society, but the price they have to “pay” in exchange for the protection of property rights, or in exchange for creating a company or trust that enjoys limited liability (that protects the company owner from the company’s creditors).

As the figure shows, disclosing only the legal ownership, rather than full beneficial ownership, is cheating on this basic contract. Just as we wouldn’t recognise ownership of something purchased with fake money, society shouldn’t recognise property rights or limited liability over assets whose beneficial owners are hidden.

On the bright side, things are improving. The 2020 edition of the Financial Secrecy Index shows that more than 80 countries now have beneficial ownership registration laws. Going further than just registration as we have been demanding for many years, many countries are also starting to make information from registration publicly available. This is especially true in EU countries, based on the 5th anti-money laundering directive (AMLD 5). The UK has been providing this information since 2016 and it has requested this from its Overseas Territories (although that can has been kicked way down the road) Now more countries are following, including in Latin America.

The next step however, is for beneficial ownership of other assets, including real estate, cars, yachts or planes, to also be made public. The Financial Secrecy Index also assesses countries on this under our indicator 4 “Other Wealth Ownership”. In addition, proposals on beneficial ownership of assets were also made at a workshop for a Global Asset Registry co-organised by Tax Justice Network in Paris in 2019. In relation to this, the Independent Commission for Reform of International Corporate Taxation (ICRICT) in 2019 published a scoping study of the UK asset ownership registries for real estate, gold, racehorses, bitcoins and other assets. These asset ownership registries would be relevant to measure inequality, apply wealth taxes and detect illicit financial flows.

Trusts vs Wills: the secrecy benefits that were never justified

Lehavi, whose paper we mentioned above, starts with one of our biggest secrecy concerns: trusts. His paper describes that while wills must become public, trusts can remain secret even from trust beneficiaries, let alone public authorities and the general public.

What is a trust?

Put simply, a trust is a three-way arrangement where a “settlor” (say a rich grandfather) gives assets (eg a bank account, or an apartment) to a “trustee” (often a lawyer) to look after on behalf of beneficiaries (for example, the grandchildren.) This often obfuscates ownership: if the grandfather has given the assets away, but the grandchildren haven’t received them yet, and the trustee only has very limited rights over the assets, then who owns them?

Wills are only confidential until the person who made the will dies. This makes sense because a will has no effect until death: that person may change or destroy it at their discretion. A will also has no effect after death if there aren’t any assets remaining to transfer, perhaps because creditors took them. After the person dies, wills must become public in order to enforce their wishes, and for legitimate heirs and creditors to become aware of the new property rights.

A trust, by contrast, can affect ownership from the moment it is created. Trust assets are shielded from personal creditors, including tax authorities. Trusts don’t always need to be registered, let alone be publicly disclosed.

We have written about trust abuses here and here, and also made the case for trust registration here. The fact that trusts enjoy immunity and secrecy benefits that aren’t available to wills or to companies can only be explained by the way financial elites and their enablers work: secretive vehicles and regimes can be created with complete disregard for current laws or consequences, to serve just a small number of powerful people.

Another paper by Adam Hofri-Winogradow, another authority on trusts, refers to this:

Given that self-settled spendthrift trusts [a kind of trust often abused by wealthy people] leave settlor-beneficiaries’ creditors, including spouses, tort victims and governments, empty handed and perpetual trusts [ditto] leave the public fisc wanting, if even the professionals who lobbied for them are not enriched by them, it is unclear what merits, if any, they have.

Still, in what may be considered “divine justice” or karma, trusts often turn against the people they are meant to benefit.

Trusts separate out different aspects of ownership: technical legal ownership of assets (giving power to buy and sell the assets, for instance), the power to control and use those assets (such as telling the directors of a company held in a trust what to do) or power to enjoy those assets (such as rights to live in a luxury apartment or castle held in a trust.) As the box above shows, trusts can place assets in a kind of limbo where nobody at all can legally be identified as the owner. So creditors of one of the parties to a trust – for example, the rich grandfather who put assets into the trust – cannot access those assets if they need to — because they don’t own those assets any more. Many trusts can be said to hold ‘ownerless assets,’ in a kind of legal limbo, like an impenetrable legal fortress into which only a select group of invitees may have access. In the words of Brooke Harrington, a leading author on trusts and wealth management:

‘People can get sued and lose or incur debts they can’t cover, but if their assets are in a Cook Islands trust, they can say, “Meh, I don’t feel like paying. Come and get me”’. (source: Finance Curse, p186.)

For a trust to work “effectively” as a shield against creditors or as a veil against authorities, legal ownership must be pushed to its limits. Settlors and beneficiaries need to appear so distant from the trust ownership and control, and the trustees must appear to have so much independence and discretion that there are plenty of cases where trustees are able to steal the whole wealth for themselves. The “Offshore Alert Conference” 2019 held a session entitled: “Liechtenstein’s Modern Day Grave Robbers – Stealing The Assets of Dead Clients”:

In the early 1990s, Information Technology specialist Klaus Lins claimed to have discovered evidence that a Liechtenstein fiduciary was misappropriating the assets of wealthy clients when they died, instead of distributing them to beneficiaries… More recently, the family of Israeli tycoon Israel Perry has been waging a bitter legal war against a trust company in Liechtenstein in a so-far vain attempt to gain access to the deceased’s vast fortune.

The network of tax havens, secrecy jurisdictions and especially those private enablers of the system hurt everyone: not only government and the public, but even in many cases the wealthy they are meant to protect.

Control over listed companies, section 13(d) and hedge funds

Lehavi’s paper is also illuminating on privacy and transparency arguments related to US Securities Exchange Commission (SEC) regulation 13(d) which requires the disclosure within 10 days of any person acquiring at least five per cent of the capital of a company listed on the stock exchange (because of the control it could exert through that five per cent).

We have already written (“Beneficial ownership in the investment industry”) about the shortcomings of such rules: for example, they can be evaded by investing via different entities and funds or custodian banks, for a total above five percent. While five percent may be relevant in terms of control for a listed company, it is too high a threshold in terms of money: just 0.1% of Apple is worth around US$ 1.5 billion, representing a huge potential tax evasion or money laundering risk.

What Lehavi’s paper highlights, however, relates to an “efficiency” argument made by none other than hedge funds, claiming “positive externalities” from secrecy. The paper describes the arguments presented by hedge fund lawyers:

“outside blockholders [eg hedge funds or other large shareholders not involved in the management of the company] with a significant stake have stronger incentives to invest in monitoring and engagement,” making incumbent managers more accountable and reducing agency costs and slack… secrecy is even more necessary to enable the benefits for corporate governance because a key incentive to become a blockholder lies in its “ability to purchase shares at prices that do not yet fully reflect the expected value of the blockholder’s future monitoring and engagement activities.” If an investor cannot do so, the returns on becoming an active blockholder fall and other shareholders lose the benefits of its presence. Publicly disclosing the presence of an outside blockholder too early might therefore perpetuate agency problems and managerial slack to the detriment of shareholders as a group. Secrecy therefore creates positive externalities.

In plain English: hedge funds (who pool money from sophisticated investors, either other investment funds or high net worth individuals), are meant to add value to the corporation in which they invest (and hence the economy, and hence the world) because they have an incentive to monitor and reduce slack in the management of these corporations. But, it only makes sense to them to do this good monitoring (to the benefit of all of the human race) if they can keep their share purchases secret for 10 days, so that selling shareholders don’t raise their prices after realising that a rich buyer is in town.

This argument reminds us of trusts in the sense that their existence is defended based on potentially good outcomes that may occur, while nothing in the law guarantees that such a positive outcome will actually happen. Those who defend trusts (especially discretionary trusts with asset protection features) invoke the need to help provide for the family or help the poor. Yet, nothing in the law obliges trusts to help vulnerable people. A trust may be created to benefit only the same settlor who created the trust. In fact, some news articles show millionaires and billionaires use trusts to rip off their soon-to-be-ex-wives).

Back to the hedge funds discussion. It would be one thing if the law required hedge funds to maintain their investments unchanged for a long time, show how they improved management and how the company and all stakeholders are better off. But if nothing prevents a hedge fund from taking control only to engage in self-dealings or to stay just for the right amount of time only to sell those shares at a premium (without doing much monitoring), we cannot be so sure that it will benefit anyone but themselves. And there are good reasons to worry about the negative effects that has on economies.

However, the main reason we should question whether “secrecy” is the right way to ensure hedge funds will buy their shares at a cheap price doesn’t have to do with illicit financial flows (although, US hedge funds don’t even need to check for anti-money laundering purposes the origin of the millions and billions invested in them, unlike any local bank when you try to set up an account). The point here is about inequality. Do we really want “more secrecy” to make it cheaper for hedge funds to amass even more wealth, especially when their lack of transparency means we don’t even know who’s benefitting from them?

The power struggle: privatising the elite’s information and socialising the general public’s data

The big element missing from Lehavi’s paper involves power.

Access to information is ultimately about power. Powerful people (authorities, secret services, IT companies, credit card companies, banks, lawyers) already have access to a trove of personal information on most of us: what we own, what we owe, what we buy, where we go, what we like. As one article puts it, Google knows you better than you know yourself.

By contrast, ordinary people know little about those with wealth and power: how they got their money and assets, the taxes they pay (or not), or whether, or how they are influencing politics, or illegally obtaining government contracts. According to Oxfam, “the world’s richest 1% have more than twice as much wealth as 6.9 billion people”. Extreme inequality in access to capital, ownership of media, procurement processes, or financing of political parties is undermining our democracies and our justice systems.

To argue that we should defend the “privacy” of the owners of capital – in the name of liberty and freedom – is a bit like advocating for a fascist political party to run for election because we believe in democracy.

Rules on disclosure are there as protection for ordinary citizens against powerful predatory behaviour. Undoing those protections in the name of “freedom” raises the question: whose freedom do we value the most? Giving the fox more freedom in the henhouse isn’t the best course of action.

It’s precisely because we love democracy and freedom that we should establish limits to ensure that no one has so much power (and information) that they are above the law.

In practice, privacy doesn’t mean that no one knows anything about anyone, as financial elites and their enablers claim. What it really means is that a few (may) know everything about everyone, while most know nothing about those in power or those at the top of the tree economically.

Related articles

The Financial Secrecy Index, a cherished tool for policy research across the globe

Vulnerabilities to illicit financial flows: complementing national risk assessments

Do it like a tax haven: deny 24,000 children an education to send 2 to school

Tax Justice transformational moments of 2024

Did we really end offshore tax evasion?

How ‘greenlaundering’ conceals the full scale of fossil fuel financing

11 September 2024

10 Ans Après, Le Souhait Du Rapport Mbeki Pour Des Négociations Fiscales A L’ONU Est Exaucé !

Another EU court case is weaponising human rights against transparency and tax justice

The secrecy enablers strike back: weaponising privacy against transparency

Privacy-Washing & Beneficial Ownership Transparency

26 March 2024