The Tax Justice Network is publishing today this open letter to the G20 alongside the State of Tax Justice 2022, which reports that the OECD decision to permit multinational corporations to disclose their country by country reporting privately instead of publicly had led governments to forgo $89 billion in corporate tax a year that should have been collected.

Date:

15 November 2022

To:

G20 Heads of state and government

Tax Justice Network Ltd

C/O Godfrey Wilson Ltd

5th Floor Mariner House

62 Prince Street

Bristol, England BS1 4QD

Dear G20 leaders,

Open letter:

OECD failure to deliver on G20 mandates

Recognising the G20’s focus on international tax issues, and the leadership of the organisation’s new president, India in strengthening work on tax matters at the United Nations, I am writing from the Tax Justice Network to raise serious concerns over the OECD’s problematic stewardship of international tax rules and of a global public good mandated to it by the G20 in 2013: the country by country reporting data of multinational companies.

These concerns, set out below, relate to the failure to ensure the technical robustness of the OECD standard; the failure to make aggregate data public in either a timely or a regular fashion, as directed by the G20; the failure to deliver company-level public data, which it is estimated would cut the revenue losses due to corporate tax abuse by more than US$89 billion; and ultimately, the OECD’s failure to ensure that the organisation itself can be held accountable for progress.

The Tax Justice Network believes that our tax and financial systems are our most powerful tools for creating a just society that gives equal weight to the needs of everyone. Under pressure from corporate giants and the super-rich, our governments have programmed these systems to prioritise the wealthiest over everybody else, wiring financial secrecy and tax havens into the core of our global economy. This fuels inequality, fosters corruption and undermines democracy. We work to repair these injustices by inspiring and equipping people and governments to reprogramme their tax and financial systems.

Global tax losses and a critical accountability measure

The G20 took an important step by directing the OECD (the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development) in 2013 to develop a standard for country by country reporting. This measure, which the OECD had long resisted, has the aim of exposing and reducing the misalignment between where multinational corporations declare their profits and the location of their real economic activity.

This practice, commonly referred to as profit shifting and which country by country reporting was specifically designed to expose, was estimated at the time to cost countries billions in lost tax revenue. These estimates proved to be correct when the OECD finally published two sets of country by country reporting data seven years later in 2020 and in 2021, allowing the most precise evaluation so far.

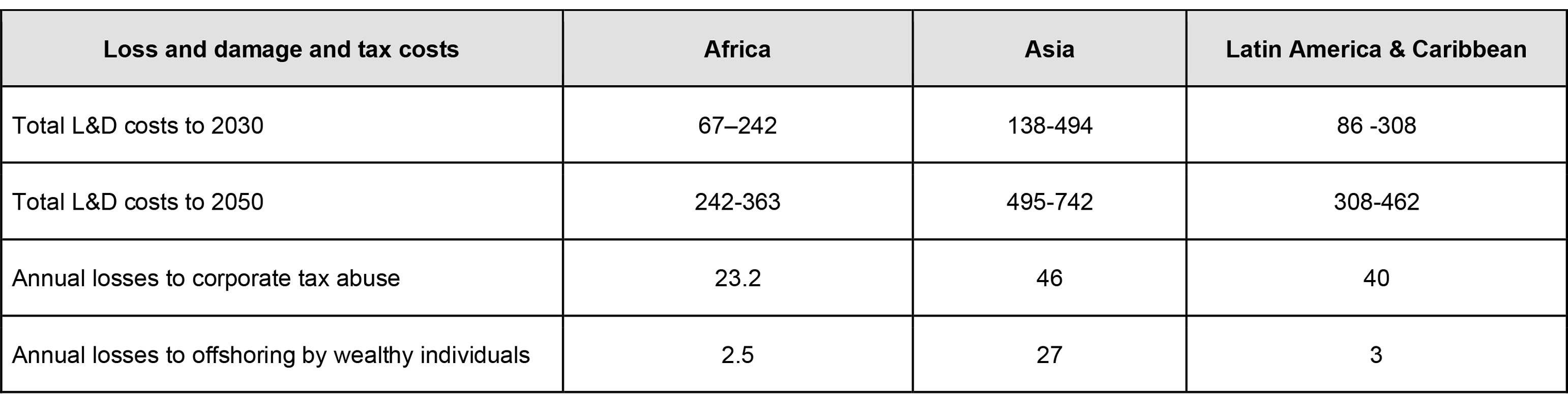

The Tax Justice Network analysed this data in the State of Tax Justice reports, published jointly in 2020 and 2021 with the Global Alliance for Tax Justice and Public Services International, to reveal that multinational corporations shifting profits offshore cost countries around the world over US$300 billion in annual tax losses, generating in excess of a trillion dollars of illicit financial flows each year.[1]

These revenue losses undermine governments and public services around the world. It is estimated that each year 17 million more people could benefit from clean water and 34 million from basic sanitation, if revenue losses due to global tax abuse (corporate and individual) were reversed. Over a ten-year period, these gains would be associated with the prevention of 600,000 child deaths and 73,000 maternal deaths.[2]

Consistent annual data supports the ongoing pressure to reform the international rules in order to curb the costs of corporate tax abuse, and assists tax authorities in targeting the most egregious cases. But the OECD has failed to meet this important mandate in multiple ways.

The OECD’s multiple failures

This year, as people and governments everywhere feel the squeeze of a global cost of living crisis, the OECD has failed to publish country by country reporting in a timely manner. Without the transparency data, neither the Tax Justice Network nor any other independent research can evaluate how much each government is losing to multinationals’ corporate tax abuse, or any progress made to curb tax losses in recent years.

The OECD’s failure to publish this transparency data in a timely manner as directed by the G20 is unacceptable and made more problematic by the heightened urgency for revenue governments face today. In the nine years since the OECD was directed by the G20 to collect and report country by country reporting data, the OECD has to date published only two years of data – the most recent of which relates to 2017.

This failure presents an important obstacle for the accountability of governments, including the G20, and of multinational companies – but it is absolutely fatal for the OECD’s own accountability.

First, the lack of data makes it impossible to assess on a consistent basis whether there has been any progress at all on the Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) initiative that is about to enter its tenth year. The single goal given by the G20 when they set BEPS in motion in 2012-13, is that the OECD should reduce the misalignment between the location of multinationals’ real economic activity, and where they declare their profits.

With its unique control of country by country reporting data, only the OECD is fully able to assess this. The OECD is thus marking its own homework, and also preventing anyone else from doing so. But the existing analysis using alternative data sources shows that far from curbing corporate tax abuse, BEPS has actually allowed it to grow more sharply.[3]

Second, the OECD’s failure to ensure timely publication of the data has meant that countries are unable to assess the revenue implications of the organisation’s proposals for international tax reforms, which again are the result of a G20 mandate. For countries outside the OECD, the lack of data is especially stark. These countries in the ‘Inclusive Framework’ are being asked, in effect, to sign a blank cheque: to give up known taxing rights in exchange for entirely uncertain returns under the OECD proposals. Despite its unique data access, the OECD has refused to publish country-level revenue assessments at any stage – although is perhaps unsurprising as all independent evaluations indicate that lower-income countries stand to benefit least from the proposals.[4]

But failure to publish in a timely and regular fashion is not the only manner in which the OECD has mishandled the country by country reporting mandate. The third failure is the failure to develop and upgrade a robust, technical standard to ensure high-quality data. The Tax Justice Network warmly welcomed the OECD standard for country by country reporting in 2015, which follows closely the original draft accounting standard that we had promoted since 2003.[5] We noted, however, significant issues in the technical robustness of the standard and the severely limited availability of the data.

Most significantly was a concession engineered by the OECD into the standard that permitted multinational corporations to disclose their country by country reporting privately to tax authorities, instead of disclose them publicly as originally proposed by proponents of the transparency measure. Under the OECD standard, tax authorities are required to anonymise the reports before sharing them with the OECD, which then aggregates and publishes the data. The anonymity conceded to multinational corporations, we argued at the time, negated the purpose and undermined the effectiveness of county by country reporting.

The OECD had committed to a review of its standard after five years of the BEPS Action Plan, and accordingly held a public consultation in 2020. The response was overwhelming, with investors and asset managers representing trillions of dollars of shareholding aligning calling for the data to be made public, and for the OECD to converge to the leading standard, that of the Global Reporting Initiative.[6] Two and a half years later, the OECD has neither concluded its review nor responded to these clear demands from stakeholders.

Costs of failure

Experience with more limited standards for public country by country reporting, including for financial institutions operating in the European Union, have provided a basis of evidence on the benefits of transparency. Banks with operations in jurisdictions identified as tax havens were seen to increase their tax payment by 3.6 percentage points once public reporting was required, compared to banks not making use of tax havens.

It is also estimated that even private preparation of country by country reporting data can increase tax paid by 1.5 percentage points, so we can discount the returns on publishing OECD reporting accordingly, which implies a 2.1 percentage point increase in tax paid. This level of response would imply a minimum return of US$89 billion through the reduction of corporate tax abuse, simply from requiring the publication of OECD reporting data. This reduction amounts to 28.5 per cent of the £312 billion in tax that countries around the world lost to cross-border corporate tax abuse in a single year, according to our analysis of the OECD’s aggregate data for 2017.

In other words, requiring country by country reporting to be disclosed publicly instead of privately makes the measure more than twice as impactful, and can prevent 1 of every 4 tax dollars lost to cross-border corporate tax abuse.

By engineering the anonymity concession into its standard, the OECD has failed governments around the world and cost them billions in revenue each year.

The Tax Justice Network, and many others, have repeatedly raised these issues over the years, most recently in an open letter sent in October 2022 to the newly appointed OECD Secretary-General Mathias Cormann from the Tax Justice Network detailing the failures in full. In his response, Mr. Cormann did not provide adequate reassurances that these issues will be resolved. While we welcome the OECD’s commitment to reduce partially the lag on their publication of aggregate data, this does not address the wider issues of the quality of the data or of the fairness of access, and we urge the G20 to revisit the OECD’s mandate.

The OECD has been left behind…

OECD staff working on country by country reporting have shown a valuable commitment to ensuring that member countries cooperate and that country by country reporting data are made available. It is clear, however, that the organisation has been unable or unwilling to provide the necessary resources to ensure that this role can be performed effectively.

As a result, the OECD is being left behind – by individual countries like the US and Spain maintaining regular and much more timely publication of aggregate data; by the EU deciding to require the direct publication of significant company-level data; by Australia now requiring multinationals’ to publicly disclose their full country by country reporting; and by the growing, voluntary adoption of the much more technically robust GRI standard.

In 2021, the UN High-Level Panel on International Financial Accountability, Transparency and Integrity (FACTI) called for the creation of a Centre for Monitoring Taxing Rights “to collect and disseminate national aggregate and detailed data about taxation and tax cooperation on a global basis”, reflecting that “[a] body with universal membership is needed to make detailed data available for analysis and research” and that “[t]he bare minimum to begin addressing the massive scale of tax avoidance and evasion is to obtain consistent annual data on a global basis.”[7]

It is, sadly, clear that the OECD is not meeting this “bare minimum”. Moreover, the OECD’s performance has deteriorated over time, missing its own deadlines for publishing country by country reporting and failing to do so at all so far in 2022. It is not possible to argue that these are early teething issues to overcome: it is, after all, nearly 10 years since the G20 gave the organisation the country by country reporting mandate.

…and the world is looking to the UN – the G20 must too

It is unsurprising then that countries of the world are already moving on to the UN. The G77 submitted last month a draft resolution at the UN General Assembly to upgrade the UN tax committee into an intergovernmental body with wider powers, while the Africa Group has proposed a resolution that would begin negotiations on a UN tax convention, as called for by the ECA finance ministers’ declaration of May 2022.[8] The UN Secretary General António Guterres has announced his support for such negotiations,[9] and draft proposals demonstrate that a convention could require publication of country by country reporting worldwide and also bring about the FACTI panel’s proposed Centre for Monitoring Taxing Rights.

We urge G20 leaders to back global calls for a new, inclusive UN role on taxing rights and to move the country by country reporting mandate to the UN, where the G20’s 2013 demand for tax transparency can finally be realised in full.

The G20 was right to necessitate the creating of country by country reporting data, recognising the need and value of this global public good. The G20 is right, too, to remain highly concerned by the scale and damage due to corporate tax abuse. But even the most starry-eyed OECD member country must recognise that the organisation has failed to deliver both on the global public good of country by country reporting, and on providing a forum for tax rule-setting that is either inclusive or effective.

We now call on the G20 to bring this global public good into the daylight of democracy at the UN, by supporting the G77 and Africa Group resolutions; by asking the UN tax committee to take up responsibility for country by country reporting data and/or by backing the creation of the Centre for Monitoring Taxing Rights through a UN tax convention; and by supporting the creation of an truly inclusive, intergovernmental tax body under UN auspices.

Only then can we achieve the tax transparency and accountability that governments of the world urgently need to end the scourge of profit shifting and recover the hundreds of billions in tax revenue they lose every year.

Yours sincerely,

Alex Cobham

Chief executive

Tax Justice Network

[1] GATJ, PSI & TJN, 2021, State of Tax Justice 2021, London: Tax Justice Network, https://taxjustice.net/reports/the-state-of-tax-justice-2021/.

[2] TJN, 2021, Tax Justice and Human Rights: The 4 Rs and the realisation of rights, London: Tax Justice Network, https://taxjustice.net/reports/tax-justice-human-rights-the-4-rs-and-the-realisation-of-rights/.

[3] Wier, L. & Zucman, G. (2022), ‘Global profit shifting, 1975–2019’, WIDER Working Paper 2022/121, Helsinki: UNU-WIDER: https://www.wider.unu.edu/publication/global-profit-shifting-1975%E2%80%932019.

[4] This includes the work of researchers at e.g. the intergovernmental South Centre and of the International Monetary Fund. See Ovonji-Odida, I., Grondona, V. & Chowdhary, A., 2022, ‘Two Pillar Solution for Taxing the Digitalized Economy: Policy Implications and Guidance for the Global South’, South Centre Research Paper 161: https://www.southcentre.int/research-paper-161-26-july-2022/; and Dabla-Norris, E., et al., 2021, ‘Digitalization and Taxation in Asia’, IMF Departmental Paper 2021/017, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/Departmental-Papers-Policy-Papers/Issues/2021/09/13/Digitalization-and-Taxation-in-Asia-460120.

[5] For a more detailed discussion of the history and development of this important tool, see Cobham, Janský and Meinzer, 2018, ‘A half century of resistance to corporate disclosure’, Transnational Corporations 25(3), https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/diaeia2018d5a2_en.pdf.

[6] See summary of submissions at ‘Investors demand OECD tax transparency’, 2020, Tax Justice Network blog, https://www.taxjustice.net/2020/03/19/investors-demand-oecd-tax-transparency/.

[7] FACTI Panel, 2021, Financial Integrity for Sustainable Development, UN: New York, https://factipanel.org/docpdfs/FACTI_Panel_Report.pdf.

[8] https://taxjustice.net/press/g7-countries-cost-the-world-115-billion-in-lost-tax-african-finance-ministers-call-for-a-un-tax-convention/.

[9] https://taxjustice.net/press/un-secretary-general-signals-support-for-un-tax-convention/

Photo credit: ©OECD/Victor Tonelli