Luke Holland ■ Putting tax justice on the agenda at COP27

The Red Sea resort of Sharm El Sheikh in Egypt is the focal point of the world’s attention this week as political leaders from all over the planet come together for COP27, the 27th United Nations climate change conference.

This latest convening comes after a series of reports giving dire warnings about the international community’s continuing failure to rise to the challenge of preventing catastrophic temperature rise. What has become viscerally clear is that climate change is no longer a distant disaster somewhere in the future. The devastating human and environmental impacts of climate change are already upon us, and the only question that now remains is just how bad it will get and how effectively humanity will be able to navigate the storm.

Given that many of the most pernicious impacts of climate change, in particular for the Global South, are now ‘baked in’, the attention of climate justice activists has shifted away from the language of mitigation and adaptation and towards the agenda of ‘loss and damage’.

The issue of loss and damage – which refers to impacts of climate change not avoided by mitigation, adaptation, or other measures – is recognised in Article 8 of the Paris Agreement, which declares that signatory countries “recognise the importance of averting, minimising and addressing loss and damage associated with the adverse effects of climate change”. Thus far, almost all developed nations – with the notable exceptions of Scotland and Denmark – have refused to make meaningful financial commitments to compensate for loss and damage, despite the fact they are precisely the ones most responsible for the historic greenhouse gas emissions that have caused the crisis.

Together with the Global Initiative on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, the Tax Justice Network is working to develop reforms to the governance of international taxation. These must be implemented in order to deliver a just transition and ensure that poorer nations in particular have the resources necessary to navigate the years ahead. As we demonstrate in a new white paper which is being presented at the COP27 meeting, these reforms are crucial to minimise the human suffering stemming from climate change.

Proposals to create a new financial facility to address loss and damage were scuppered at the last UN climate conference in Glasgow, and there is still no formal international mechanism for addressing the harms caused by climate change to the world’s poorest populations. Yet this accelerating crisis should be considered a matter of racial, gender and post-colonial justice: it is well documented that women and girls, and people of colour in former colonial states, are disproportionately impacted by climate change. A global economic system anchored in the financial and resource extraction of these countries by the Global North has caused the climate crisis, whilst also rendering countries unable to cope with the environmental convulsions they are experiencing.

Moreover, these reforms to the governance of international taxation should be considered a human rights obligation, for wealthy and poorer nations alike. This has increasingly been recognised by the United Nations human rights system. In 2019, five human rights treaty bodies issued a declaration to remind governments that human rights obligations require that they “co-operate in good faith in the establishment of global responses addressing climate-related loss and damage suffered by the most vulnerable countries. More recently the UN Special Rapporteur on Climate Change and Human Rights, following a submission from the Tax Justice Network and the Global Initiative, called for the General Assembly to “explore legal options to close down tax havens as a means of freeing up taxation revenue for loss and damage”.

Although a radical reconstruction of the architecture of international taxation will not in itself be enough to provide the redress that is now required, it will be a crucial central pillar of any effort to deliver a just climate transition. As things currently stand, countries lost an estimated US$ 483 billion in tax each year as a result of global tax abuse committed by multinational corporations and wealthy individuals. Meanwhile, somewhere between US$ 21 trillion and US$ 32 trillion is hidden from tax authorities offshore, and the ease with which multinational corporations can shift their profits into tax havens and away from the location of actual economic activity has fed a race to the bottom on corporate taxation. Indeed, average corporate tax rates have fallen from 49% in 1985 to just 23% in 2019.

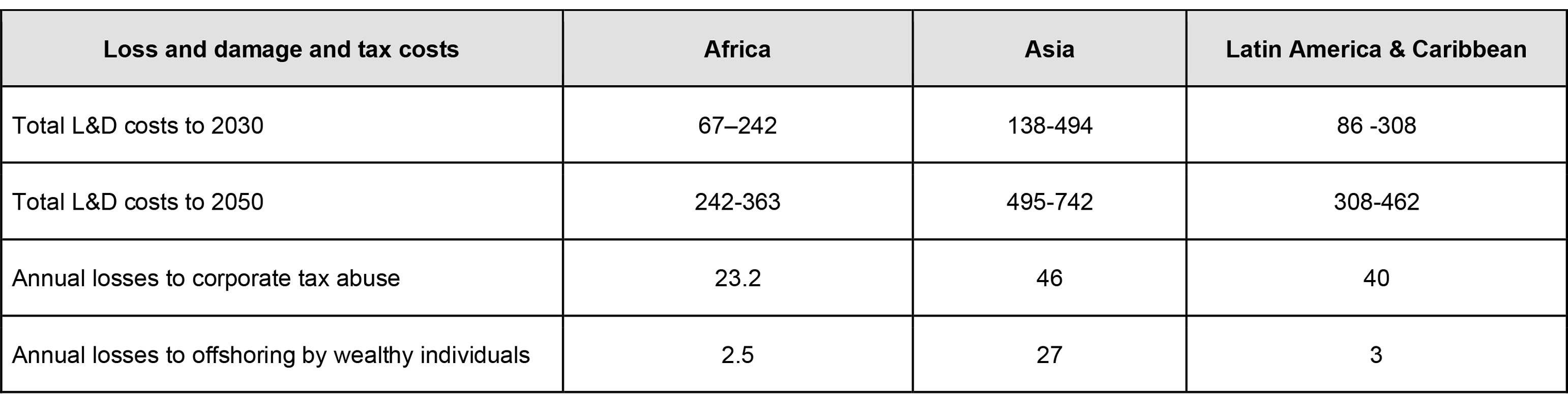

The table below, drawing on data from the Tax Justice Network’s State of Tax Justice report and the landmark 2019 study into loss and damage by Markandya and González-Eguino, illustrates the stark financial cliff the Global South is facing as the climate catastrophe gathers momentum. This grim reality gives increased urgency to the need to reform the international tax system in order to stop the pillage of government coffers everywhere.

Loss and damage and tax costs for Africa, Asia, and Latin America & Caribbean (billion USD)

Among the measures needed to achieve this are a meaningful minimum tax on corporate profits, so as to halt the ‘race to the bottom’, and the creation of a United Nations tax convention to replace the century-old system of bilateral tax treaties that place weaker nations at the mercy of more powerful states. As a necessary precondition to the latter, negotiations on international tax cooperation must be moved away from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, which has not kept its promise to include the voices of developing nations, to the UN, where all countries can meet on a more equal footing.

The climate justice and tax justice movements are not separate, or even parallel, issues. They are so intimately enmeshed that our collective success or failure in addressing each of them will be integral to determining outcomes for the other. As two highly-technical spheres, both of which require deep and determined international collaboration, bridging the gap between these two areas is no easy task. It is not hyperbole to say that the future of humanity hangs in the balance.

Related articles

Disservicing the South: ICC report on Article 12AA and its various flaws

11 February 2026

What Kwame Nkrumah knew about profit shifting

The last chance

2 February 2026

After Nairobi and ahead of New York: Updates to our UN Tax Convention resources and our database of positions

The tax justice stories that defined 2025

The best of times, the worst of times (please give generously!)

Let’s make Elon Musk the world’s richest man this Christmas!

Admin Data for Tax Justice: A New Global Initiative Advancing the Use of Administrative Data for Tax Research

2025: The year tax justice became part of the world’s problem-solving infrastructure