This long blog will be periodically updated, in response to comments. Latest update: March 28, 2019.

The international tax system for taxing multinational corporations is coming apart at the seams. We are now entering one of the most significant turning points in world tax history. As the IMF’s Christine Lagarde remarked on March 10, “we need a fundamental rethink on international taxation.”

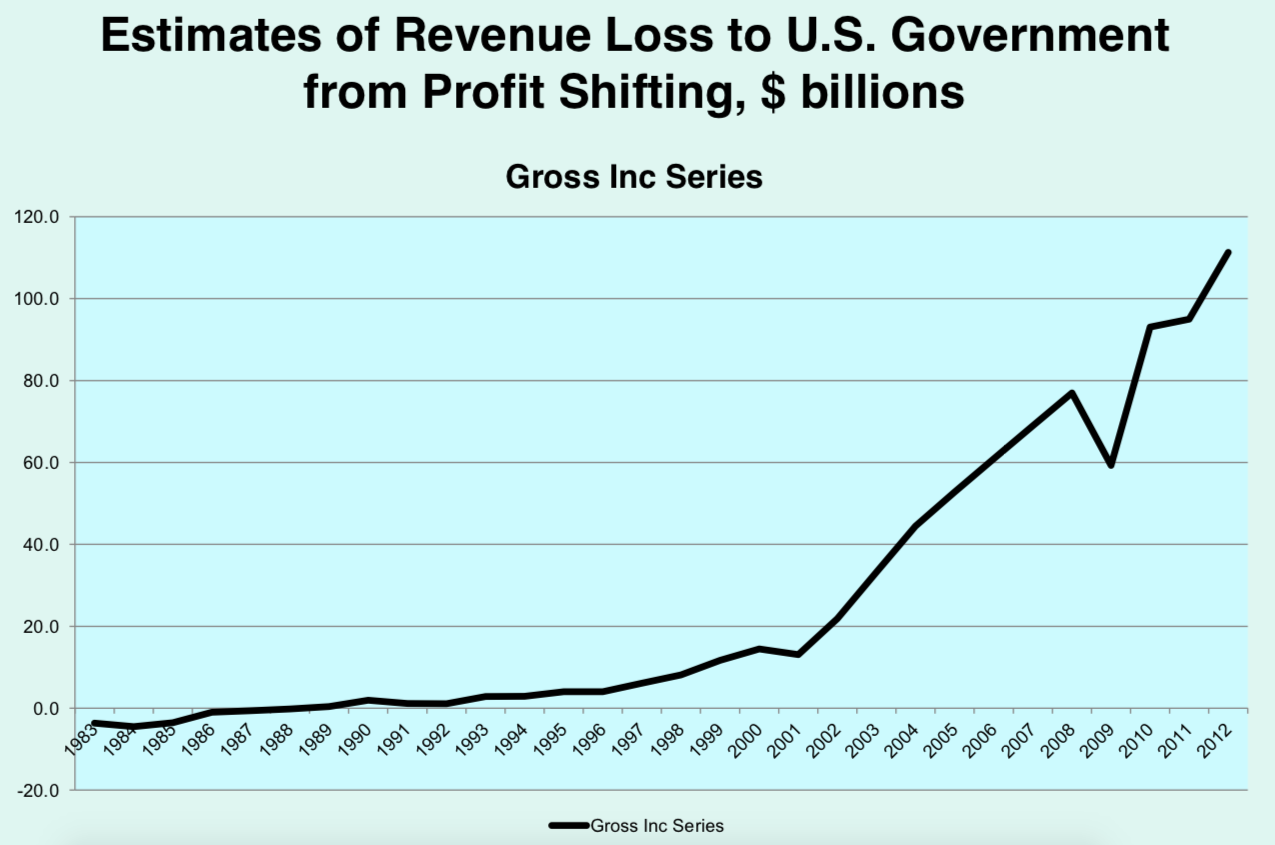

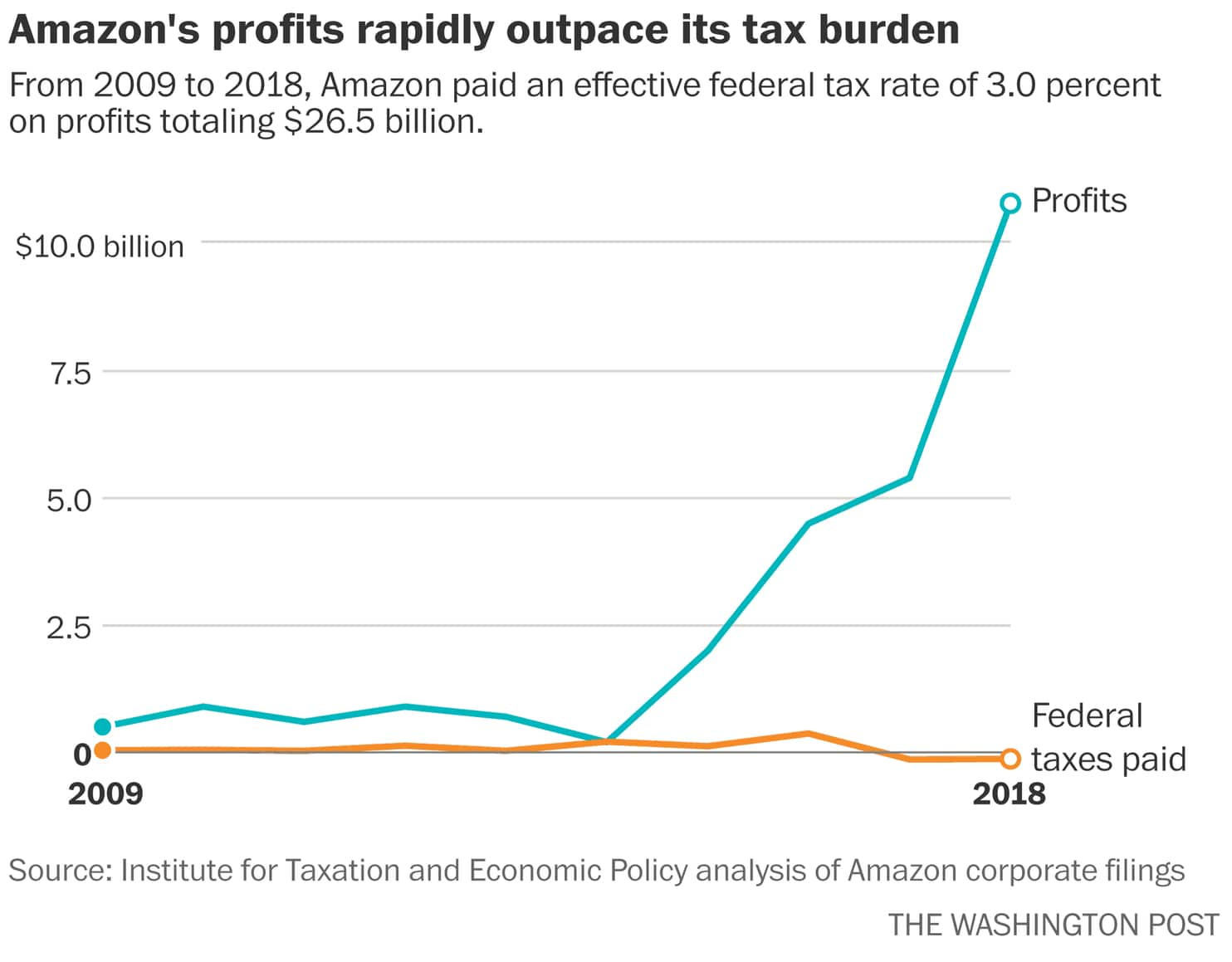

We recently noted that the OECD, the club of rich countries that has the main role of overseeing international tax rules, and the IMF, which has considerable influence (and a rather more representative global membership than the OECD) have both recognised what we’ve been saying for years: that the hallowed fundamental principles underpinning the international tax system for a century are not fit for purpose. Around $500 billion in corporate taxes are being dodged each year as a result of this failure – and it’s getting worse, as this single-country view suggests:

(Source.)

A complete revolution in international tax is now needed, and big players are waking up to the fact — so there is everything to play for, and reform must urgently be steered in the right direction. What gets decided in the next couple of years could shape international tax for generations.

There are, at present, three main competing visions of how things might proceed which have political traction. They are:

- Try to patch up the existing system. That’s what’s been going on with the OECD’s Base Erosion and Profit Shifting, or ‘BEPS’ project, which is now collapsing into complexity and incoherence because, as we’ve said, the fundamental principles underpinning the system are unworkable. The system will limp on for a while yet.

- Unitary tax, with apportionment by formula. This is the basis for our preferred vision, which we believe would be best for rich and poor countries, and would also provide the most coherent basis for taxing multinationals. There’s a very simple explainer here, a longer document here, and an intermediate-level discussion here, showing how it could be implemented partially, or in stages, and combined with a minimum tax arrangement.

- Destination-Based Cash Flow Tax (DBCFT) – which was also the heart of a dramatic tax reform proposal by Donald Trump’s administration in 2016, the so-called ‘Ryan Blueprint’ which was (thankfully) never implemented. We explain the DBCFT below.

(There are other visions, such as “Residence-based Worldwide Taxation,” discussed and dismissed here, or “Residual Profit Allocation,” discussed here. There are various hybrids of the current and alternative systems. Yet the above three are probably making the most noise.)

This blog examines the DBCFT in detail. We show that behind its superficially appealing features, it is overall a throroughly dangerous prospect, which will drive up inequality, damage tax collection, generate all kinds of shocks, fail to achieve its purported benefits, and be unworkable in the real world.

We’re motivated to write about it now because there has been some powerful support for it recently, especially in a new editorial and article by Martin Wolf in the Financial Times . Some TJNers co-authored a letter published in reply, but it’s important to put a more extensive corrective in place.

What is the DBCFT? First, the good parts . . .

This tax system confuses a lot of people, because it’s so unfamiliar (the ugly name, Destination-Based Cash Flow Tax, doesn’t help.) The explanation that follows shows the superficial attractions. We will cover the bad — deadly — parts afterwards.

The DBCFT has two main conceptual elements: the ‘Destination Based’ part, and the ‘Cash Flow’ part.

Let’s start with the destination part, which is all about what happens internationally. When a multinational based in country A (the residence country,) manufactures goods or services in country B (the country of origin for those goods and services,) and sells them in country C (the destination country) for profit, a key question arises. Which country gets to levy tax? Under the current international tax system that’s an immensely complex question, and is easily gamed by using transfer pricing, tax havens, and other tricks.

The ‘destination’ part of DBCFT means that it’s the country where the goods are destined (or sold) that gets to levy the tax. That’s Country C. The first apparent attraction of this approach is that you can’t use tax havens to escape the tax, since it is generally very clear where goods are finally sold (so you can levy tax there) — unlike in the current system where you have to work out where profits on cross-border business are genuinely created — a question that is easily tricked and gamed, as we’ve documented extensively.

How, then, does the destination country tax those transactions? This brings us to the cash flow part.

To see how this works, first compare this to the standard corporate income tax (CIT,) the basis of the current international tax system for multinationals.

A CIT is a tax on profits — that is, the amount of income that remains from gross revenues or sales, after you have deducted costs or expenses — typically inputs and salaries and other costs, including interest on debt.

So, to grossly oversimplify, take a candlestick maker who sells candlesticks this year for $1 million, paying $600,000 in salaries, $100,000 in metals, wax and electricity, and $140,000 in interest on borrowing (to pay for the factory building and equipment). Its revenues will be $1m but its profits just $160,000 ($1 million in revenues, minus those assorted deductions.) So a 25 percent CIT rate here should yield $40,000.

The DBCFT also takes gross revenues as a starting point — but then changes the rules as to what gets deducted.

What you can deduct with the DBCFT is wages. Salaries. That’s also, in itself, a good thing, because it promotes job creation.

A difference between CIT and DBCFT, however, is what happens when a firm makes a capital investment. With the traditional CIT those investment costs get ‘depreciated’ over some years – deduction after deduction until the whole investment has been written off against the tax, and if you’ve borrowed to finance the investment, you can deduct the annual interest payments too. This creates a ‘debt bias’ in the tax system that encourages companies to load up with debt. That’s a huge problem in the modern global economy, because debt is a route to large-scale rent-seeking, and it causes financial instability.

With the DBCFT, by contrast, you simply deduct the entire value of the investment in Year 1, which means you can then ignore and disallow bank interest costs as a tax deduction. This curbs debt.

For a numerical example of how the DBCFT works, see the US-based Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP) analysing the Ryan blueprint.

The overall effect of DBCFT is that you end up taxing revenues, after giving tax relief to all (non-financial) spending, including capital spending and wages. So you tax inflows, minus outflows, which is essentially cash flow. Hence the name.

The other big thing the DBCFT does is to draw a sharp line at the border. The tax gets applied to all domestic consumption (again, in the destination for the goods and services sold) — but it is not applied to goods or services that are produced locally but sold and consumed elsewhere. Imports are taxed, but exports aren’t taxed. From a national perspective many (though not all) people would see this as another advantage, because it promotes exports at the expense of imports.

Overall, the DBCFT is not a corporate tax. That’s for two main reasons. First, even though corporations would fill out business tax returns and it might seem as if they are paying the tax, the fact is that they would pass the tax straight through to consumers through higher prices. Second, it is a tax on all business activities, including those activities carried out by private individuals. (If individuals were exempted, they would enjoy a huge price advantage, decisively undercut corporations on domestic sales, and drive much of the corporate sector out of business.) So, unless all private imports were banned, it would have to be applied across the board.

These features, tied together, mean that the DBCFT ends up abolishing the CIT and replacing it with something like a consumption tax, or a Value Added Tax, applied locally, but with local labour costs deducted.

The attractions — removing incentives to increase debt, tackling rent-seeking, promoting job creation and exports — seem at first like a powerful package in its favour.

The ten deadly flaws

Despite these superficial attractions, the DBCFT is a crazy — and dangerous — bull-in-the-china-shop proposal. The ten reasons below aren’t in order of importance – each point below is probably enough on its own to make the proposal unworkable.

First, it would be likely to create negative revenues in large numbers of countries. In his letter in the Financial Times in response to a Financial Times editorial accompanying Wolf’s article, the US-based trade (and tax) economist Will Martin explained that “the net revenue base of such a tax is private final consumption less wages, which is negative for many, perhaps most, economies.” He clarified, via email:

“If the consumption share in the economy is below the wage share, tax revenues will be negative. . . They are even more likely to be negative if large parts of private final consumption can’t be fully taxed, which is certainly the case—think of the services from owner-occupied houses, output of nonprofits, and financial sector output. Even without these exclusions, revenues would be hugely negative in countries like France and Germany.”

A problem that few seem to have noticed (even the IMF is guilty of this, it seems) is that a significant part of measured tax revenues would not be tax revenues in economic terms. That’s the part that involves government consumption. When the government receives these (effectively, sales taxes) from the goods or services that it buys, those revenues are real, but in economic terms they are negated by the fact that those very taxes increase the cost of those goods and services by the same amount. So the government raises tax revenues from its purchases of goods and services, but then has to spend the same amount extra due to higher prices it paid for those goods and services: so it’s basically back where it started.

For more details on negative revenues, and much more, see Martin’s paper in The World Economy, analysing the DBCFT and the Trump administration’s proposal, which seems to be one of the only (if not the only) peer-reviewed papers on the subject.

Second, if one large country adopted it, it would create intolerable ricochets and spillovers onto other countries, piling pressure on them to follow suit, whether they wanted to or not. This is because any profits shifted into a DBCFT-implementing country would be untaxed, creating massive incentives for multinationals to do so. Also, foreign investors in a DBCFT-implementing country would face a zero tax rate on any profits earned from export markets. Other countries would be furious at seeing capital sucked out of their countries, and would retaliate. A DBCFT would substantially increase international antagonisms, at a time when the world really doesn’t need this.

Third, it would penalise developing countries in particular, which rely heavily on corporate tax revenues (because it’s hard to tax large numbers of poor people, so corporate taxes are especially important as an alternative source of revenue in such countries). As the International Commission for the Reform of International Taxation (ICRICT) pointed out recently, “developing countries with small consumer markets, especially those relying on exports of mineral resources, would raise little revenue through DBCFT as exports would not be taxable and profits will only be taxed in the country where sales to the exporting MNE’s ultimate customers take place.”

Now there’s a proviso here. Mike Devereux, the leading worldwide proponent of DBCFT, in his response to our co-authored letter in the Financial Times, stated that:

[the] claim that the DBCFT would “reapportion taxable income from the world’s poorer regions and states to the richest ones” is refuted by empirical evidence from the International Monetary Fund that “developing countries would on average be beneficiaries of a move to a DBCFT”.

Here’s the full IMF paper — and it does in fact say these particular words. However, this in no way refutes our statement: the opposite, in fact. Those IMF calculations are drawn from a model which assumes ‘universal adoption.’ In other words, every country in the world would have to adopt DBCFT, for this model to hold up. That ain’t going to happen, not least for reasons outlined in this blog: lots of countries will get negative revenues.

What is more, the IMF assumptions don’t take into account the problem of how difficult it is to collect the tax — an especially big issue in developing countries where collection is generally much weaker. (What is more, we believe that the IMF paper in its modelling doesn’t take into account the large ‘government consumption’ issue in the first point, above.)

Fourth, the CIT serves many key purposes, beyond just raising revenue, so abolishing it would do away with many of its key functions. The most important, perhaps, is the CIT’s role in serving as a backstop to the personal income tax system. That’s because if you cut corporate tax rates too far, rich folk will arrange to convert their ordinary income into corporate forms, paid into shell companies, in order to pay the lower corporate rate instead of the ordinary income tax. This cannibalises the income tax system, and the revenue losses are potentially enormous. (This is one of the main reasons why most countries set up the CIT system in the first place.) The DBCFT removes this prop to the income tax system. That’s because it’s a sales-based tax, and these personal shell companies aren’t generally in the business of making sales: they are set up to accrue (and defer) income and capital gains.

In a related matter, the corporate income tax also penetrates many trusts and other fortress-like vehicles for holding unaccountable wealth: even if the beneficial owners of such vehicles may be able to escape paying tax on their income, the underlying corporate holdings generally do pay CIT. So it serves many other vital purposes, and its abolition would generate a wide range of harms (as we noted in our document Ten Reasons to Defend the Corporate Income Tax.)

Fifth if this tax were adopted by one or more large economies it could create huge shocks to the world trading system. Experts disagree on how or how extensively this might happen. The large effective import taxes would likely be one source of shocks, which could trigger trade wars and might – though opinions are divided – trigger major challenges at the World Trade Organisation (WTO). Now it’s true that current global trading rules and the WTO are indefensible — but we don’t oppose the general principle of cross-border trade, and this bull-in-the-china-shop tax system isn’t the way to fix it.

Sixth, a DBCFT could create massive, disruptive price changes in countries that adopted it. That’s because the DBCFT implies imposing the equivalent of a Value Added Tax (VAT) onto swathes of goods and services across the economy. A 20 percent rate would be equivalent to a 25 percent VAT rate: meaning a 25 percent price rise. Slap that on top of a VAT at, say, 25 percent, that implies consumer taxes of 56 percent (that is, 1.25 x 1.25, in percentage-rise terms), vastly above the current highest rate in the world, Hungary’s 27 percent. Some say that the exchange rate would appreciate, mitigating the price effects, but in truth, as the next point explains, the outcomes would be extremely uncertain.

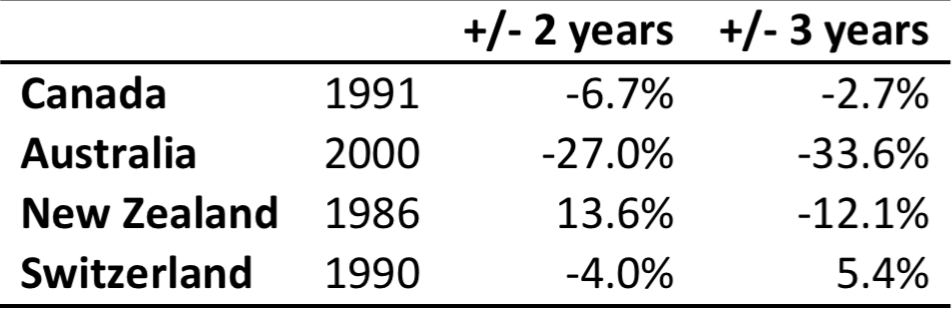

Seventh, it would likely create violent shocks to exchange rates, due to changing trade patterns and price levels. This would throw all sorts of economic policy-making, and monetary policy, into turmoil. Here’s what happened when four countries introduced a VAT:

(Source.)

In truth, nobody really has a clue how a DBCFT would play out in exchange rate terms. As the tax experts Reuven Avi-Yonah and Kimberly Clausing explain, in a paper on the US proposed version of DBCFT:

“Empirical studies in international finance makes it quite clear that exchange rates movements are divorced from most coherent theories of exchange rate determination.”

What is more, exchange rate appreciation isn’t a free lunch: it involves winners and losers, within and between countries. Much would depend on, among other things, how monetary authorities react.

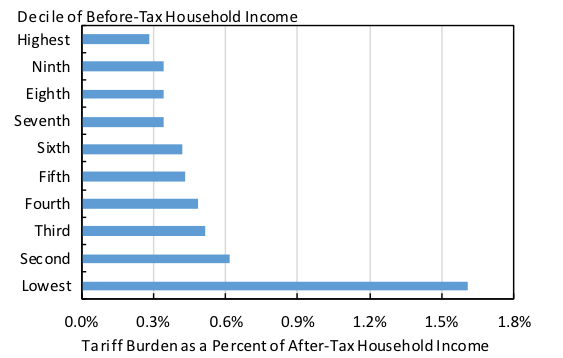

Eighth, we’ve already suggested (Point 3 above) that the DBCFT would likely increase inequality between countries – poorer countries would lose revenue – but it would also likely increase inequality within countries. That’s because VAT is generally a regressive tax which falls more heavily on the shoulders of poorer sections of the population — and if a DBCFT were to replace a corporate income tax, which tends to fall heavily on the shoulders of rich capital-owners, then this could profoundly worsen inequality. It’s true that the deduction for wages would help workers, and violent swings in exchange rates and trade flows could also — but this could also easily go the other way too. Given how regressive VAT is, higher inequality is likely. What is more, the effective tariffs on imports may have regressive effects, as this analysis suggests:

(Also see, for example, the US economist Adam Posen’s analysis, and ITEP’s analysis.)

Ninth, this tax would have powerful procyclical effects, worsening boom-and-bust in the countries that adopt it, and yielding highly volatile revenues too. This is in contrast to the CIT, which tends to smooth economic fluctuations (profits are cyclical, and a tax on profits tames the cycles.) For more on this, see the IMF paper, and the section entitled “Cyclicality.”

There are a couple of reasons why tax revenues themselves would also be more volatile. It’s partly because of the ability of firms immediately to deduct large investments, creating large sudden holes in tax revenues. More importantly, though, it is because the DBCFT is an effective sales (or consumption) tax combined with a deduction for wages, which is the difference between two large and similar-sized numbers — which, as any mathematician will tell you, inevitably yields a volatile result. In the US, for instance, these numbers have ranged between 60-66% of GDP for wages, and 60-68% for personal consumption since 1950. (For more on this, see here, especially from p11.)

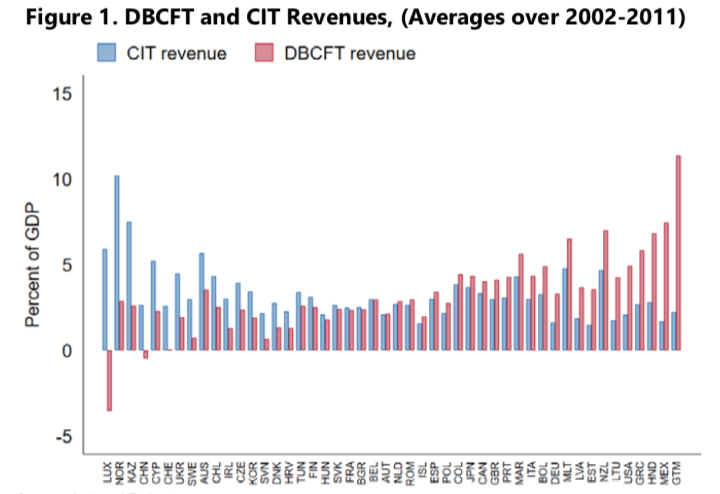

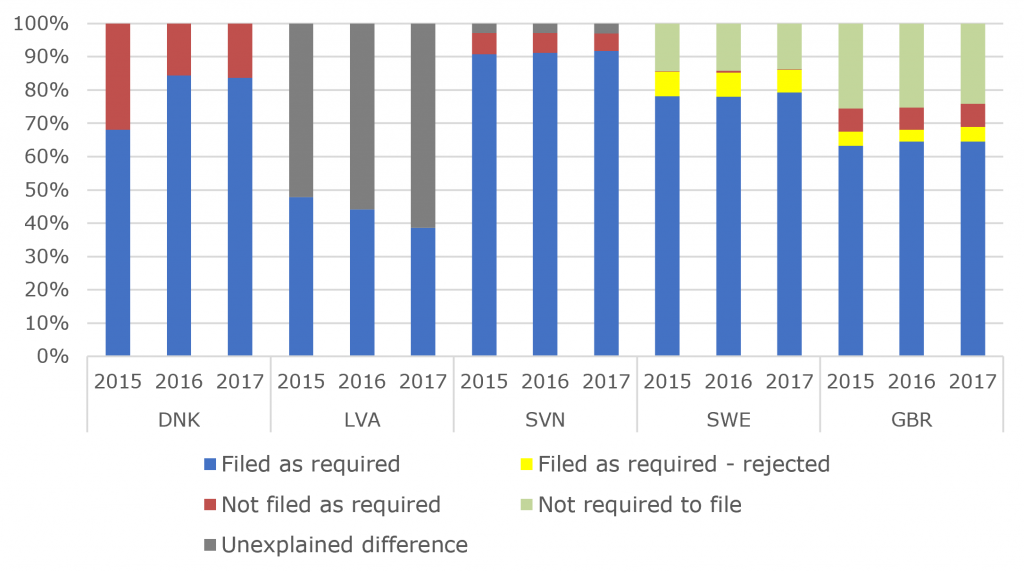

Tenth, for the reasons outlined in our second point, the system (if only adopted by some countries and not by others,) could make profit-shifting worse, not better, sucking profits out of countries that don’t implement DBCFT, and into countries that do. The IMF graph (admittely, with the above provisos) suggests that there would be a wide range of winners and losers from (universal) DBCFT, meaning that lots of countries would have strong grounds for resisting the new system.

The IMF paper agreed strongly with this assessment, and another IMF paper this month put it even more starkly:

“If only some countries adopt a destination-based cash flow tax, those maintaining an origin- based system would experience dramatically increased incentives for outward profit-shifting.”

And it may be just as hard to crack down on profit-shifting as the current system, as ICRICT noted:

“it would raise difficult practical questions of taxing a MNE with little or no physical presence in the jurisdiction, so effective collection would need cooperation between states.”

More rent-seeking, not less?

For several of the reasons given above, the DBCFT would do away with one form of rent-seeking — the current bias in favour of debt — and introduce several others, including major new ways to free-ride off the public services paid for by others. Abolishing the corporate income tax would create one huge set of unearned windfall gains for many corporate players. The knock-on effect of cannibalising the personal income tax would be another.

In addition, a whole range of new tax planning opportunities would open up, and the introduction of a massive effective consumption tax would create large new incentives to find escape routes.

Consider, for instance, the prospect of companies, especially rent-seeking companies with low overheads (such as technology firms) locating themselves in DBCFT country in order to export goods and services to other nations, thus paying no tax. They would be free-riding off the the taxes paid in both jurisdictions.

Or try this possibility, outlined in an article in the Columbia Law Journal entitled Tax Planning Under the Destination Based Cash Flow Tax: A Guide for Policymakers and Practitioners.

Deductions could be generated by making capital investments that may be immediately expensed. For example, a taxpaying company operating under a DBCFT could generate deductions by buying business assets and leasing them (especially to companies – like exporters – that could not use the deductions that would be generated from purchasing the equipment). Likewise, a taxpaying company could buy a building, and lease it back to the seller. The purchase of the building would generate a deduction, which could shelter other income.”

That paper provides a smorgasbord of other tax planning strategies for the DBCFT. And ITEP

outlines another set, including the line that it would likely prove to be a “bonanza for financial companies.” And if a DBCFT were implemented, tax advisers would get busy designing others.

The better alternative

All in all, the DBCFT is a rather large wolf in somewhat skimpy sheep’s clothing.

The better alternative, as we’ve mentioned — the only reasonable alternative, we believe — is some version of Unitary Tax with Formula Apportionment. We’ve just made a submission to the OECD on this basis.

With such a system, you take a multinational’s total global profits. Then you apportion or allocate those profits between countries according to a formula, which may be based on (for example) how large its sales are in each country, and also how large its workforce is in each place. Then that country can tax their allocated portion of global profits at whatever rate you like.

This is also the approach favoured by ICRICT, and it is also examined favourably in another new IMF paper. Curiously, the leading academic proponent of the DBCFT, Mike Devereux, co-authored an article apparently in favour of this system in 2009. It’s not clear why he changed his mind, given that he had previously proposed the DBCFT in 2002.

This way of setting up the international tax system would of course have its own difficulties and complexities, but it is without doubt the most rational and internally coherent system, and the way forward for tax justice.

Now, with the international tax system starting to come apart at the seams, it’s time to push for the right approach.

And the Destination Based Cash Flow Tax isn’t it.

Further reading