Read and share your comments on the Tax Justice Network’s new working paper on beneficial ownership and investment funds, available to download here. The paper proposes new transparency measures since neither beneficial ownership registries or the OECD’s Common Reporting Standard (CRS) for automatic exchange of information are sufficient to address the secrecy created by investment funds and financial assets.

After the Panama Papers, the need for beneficial ownership registries to identify the individuals operating behind companies and other legal persons became largely undisputed as a way to tackle illicit financial flows related to corruption, money laundering, tax abuse and the financing of terrorism.

Transparency improvements, especially in the EU, focused on expanding registration requirements for trusts and on giving public access to beneficial ownership information. As the Financial Secrecy Index showed in 2018, more than 40 jurisdictions already had, or committed to have, beneficial ownership registration.

By 2019, the number of jurisdictions with beneficial ownership registries had become even larger, and more countries committed to making their registries publicly accessible. Despite the progress, there remains one tiny loophole with astronomical consequences: there is no public information on the beneficial owners of investment funds or companies listed on a stock exchange, even though trillions of dollars are invested there.

For example, during an investigation into a potential conflict of interest involving a group of companies related to the family of Argentina’s president and a public tender for wind energy fields, Emilia Delfino described how it was impossible to identify the individuals who financed part of the contract because they used an investment fund. When trying to obtain information about the investors, Argentina’s securities regulator refused to disclose them invoking “stock market confidentiality” (secreto bursátil).

Not within the scope of beneficial ownership registries

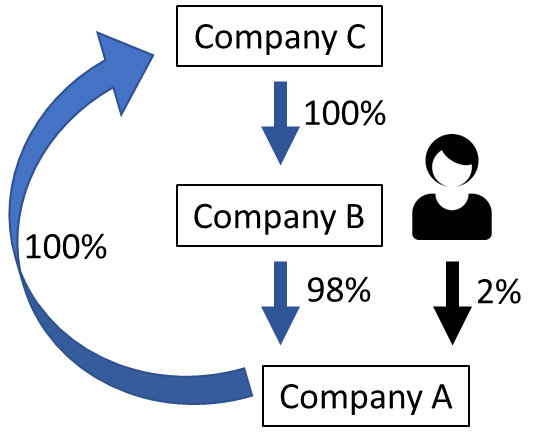

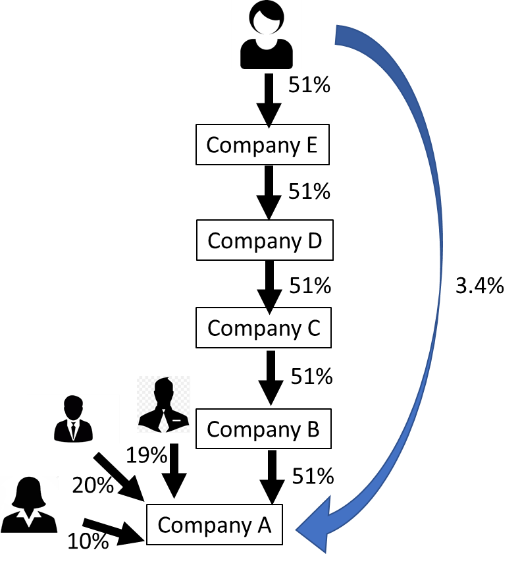

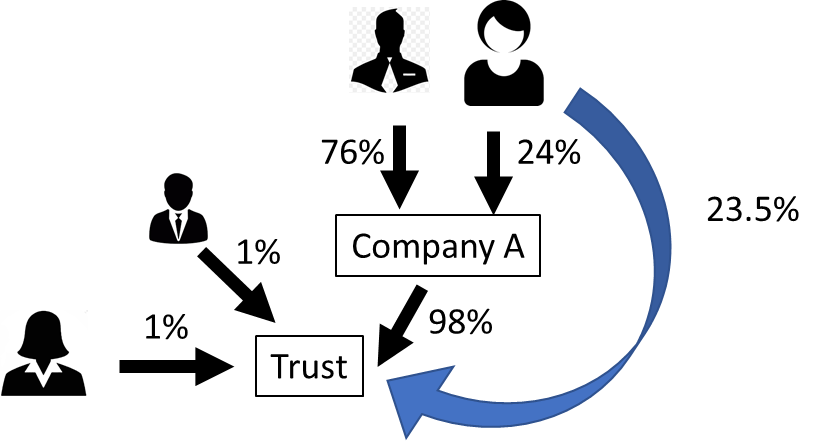

Firstly, investment funds and listed companies are exempted from beneficial ownership registries either altogether by the law[1] or in practice. Secondly, even companies that are covered by beneficial ownership registries may add secrecy to the investment industry.

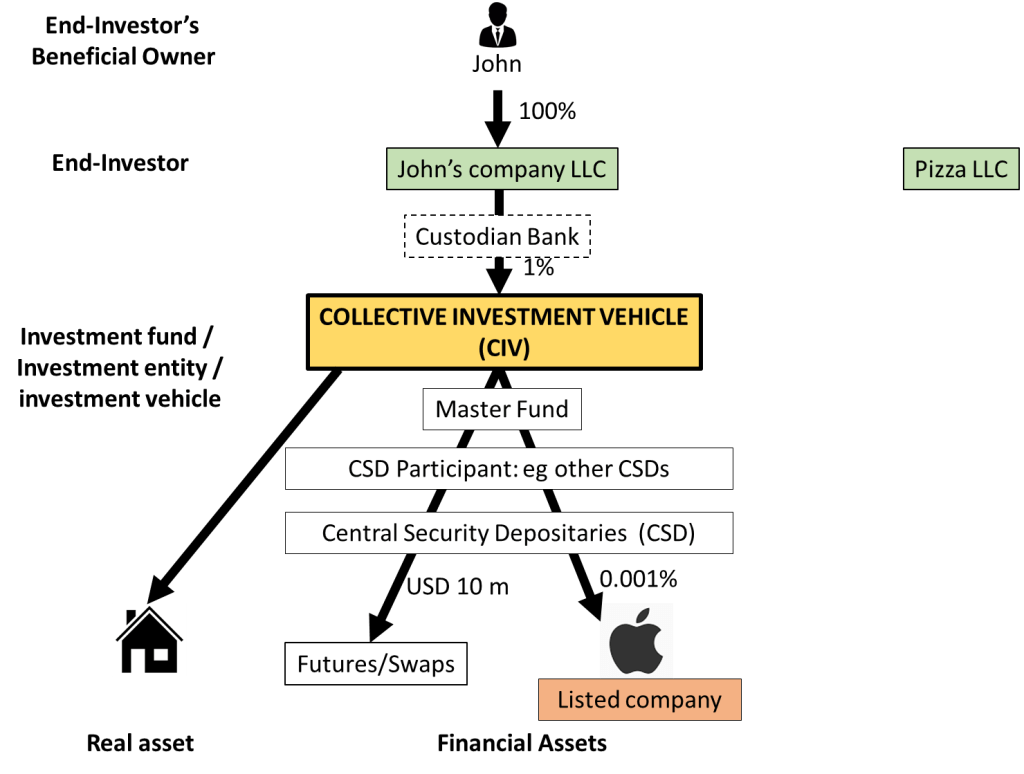

Legal vehicles such as companies and trusts may be creating secrecy in the investment industry in three different instances (marked with three different colours in the chart below).

First, the investor (John) could decide to invest his money through an entity instead of directly under his name, for example through a limited liability company (LLC) called “John’s Company”. This would create the first transparency obstacle. While this company would probably be subject to beneficial ownership registration (if the country has such a law), nothing would indicate that this company is an investor. It would look like any regular company.

Second, the investment fund may be organised as a trust or a limited partnership (which are not always required to register their beneficial owners). Even if they are registered, investors would likely own less than 1 per cent of the fund, so if the fund is organised as a company or partnership, the investor wouldn’t pass the threshold to be identified as a beneficial owner.

Third, through the possible assets held by the investment fund, either real assets (eg real estate) or financial assets (eg financial instruments like futures or swaps), the investment fund may hold shares of a company listed on the stock exchange. Listed companies, despite being companies, are usually exempted from registration, and even if they had to register, investors such as John would likely hold less than 0.01 per cent of the company’s shares, which is far below the beneficial ownership thresholds.

The rationale for these exclusions is that companies listed on a stock exchange and retail investment funds are already subject to high regulation and other disclosure requirements, including publishing a prospectus, appointing an independent auditor and so on. But this is clearly no replacement for identifying the individual investors ultimately owning or benefitting from financial assets (eg shares of a listed company) through investment funds.

The other argument, which we tackled in this blog, is that if an investor has less than one per cent of an investment fund or listed company, they clearly have no control to decide on anything. Besides, the argument goes, companies listed on a stock exchange are already required to disclose who owns more than 3 or 5 per cent of their shares.

However, control and decision making is not the only point. Not only does reporting about 3 or 5 per cent rely on self-reporting by the investor (and so is hard to enforce), but even a much lower ownership may still be extremely relevant. As of September 2019, the value of 0.1 per cent of Apple’s shares comes in at USD $220 million! Identifying the individual ultimately owning this 0.1 per cent would be key for anyone measuring inequality or for any authority trying to find out whether this person is able to justify how they afforded these shares in the first place, and whether they have paid the applicable income, capital gains or wealth tax on them.

In 2019, the Investment Company Institute reported that the total assets invested in mutual funds, exchange-traded funds and institutional funds was more than USD $46.7 trillion. Preqin reported that assets invested in “alternative investment funds” such as hedge funds, real estate funds and private equity funds was USD $8.8 trillion in 2017. Investment funds do not always hold these assets long-term. Usually they engage in securities trading or other financial transactions, where financial assets may be held for just a few seconds. In 2018, the total value of financial instruments processed in the US was USD $1.85 quadrillion (USD $1,850 trillion). To put these astronomical numbers in perspective, in 2017 the US gross domestic product (GDP) was ‘merely’ USD 19.4 trillion.

Does the OECD’s Common Reporting Standard (CRS) for automatic exchange of information solve the secrecy?

Not really (mainly because it is not meant do it, anyway). There are several loopholes, which we have written about, undermining the Common Reporting Standard that are at play here. The main one is that not all investment funds nor all investors are covered by the standard, mainly because not all financial centres are participating in the framework (eg the US). In addition, there is no reporting on wealthy individuals resident in developing countries unable to join the standard’s automatic exchange system, nor on local residents (an investor holding an account with a financial institution resident in the same country). Lastly, even for investors who are covered, exchanged information only covers the income and value of their investment, without always disclosing which investment funds they hold interests in or the underlying securities that they ultimately hold.

So no one checks anything?

Custodian banks, investment fund managers, central securities depositories, and regulators all have obligations to make anti-money laundering checks, but the industry’s structure involves many different intermediaries where many have partial information but no one has a full picture. This makes it almost impossible for anybody to know who ultimately owns what, and how they own it. The use of omnibus accounts by these intermediaries where money and financial assets from many different investors are pooled together doesn’t make the job any easier either. In other words, only one intermediary may have access to the identity of the end-investor who put money into the investment fund. Other intermediaries would only see an omnibus account without being able to identify (and run checks) on each end-investor and without being able to identify the origin of their money to detect money laundering and other illicit financial flows.

In addition, the intermediaries who may be in touch with the end investor are usually banks or other financial institutions that don’t always have the best track record. Either because of negligence, lack of available information, wrong incentives or lack of enforcement, history has repeatedly shown that banks and other financial institutions have, at best, been unable to prevent major money laundering schemes and, at worst, have been actively involved in helping individuals engage in tax abuse. The recent Cum-Ex scandal is a stark example.

One could argue that anti-money laundering laws and other regulations on banks became stricter in the past years. Still, some scandals (eg Danske Bank, the Cum-Ex files) broke out only in 2018, suggesting that not much – or at least not enough – has changed.

Another concern is that values involved in the investment and asset management industry may involve a lot of money, especially many wealthy people. One would think that the more money involved, the more risk and the more checks carried out by banks. It appears the opposite is true. A comment we heard by corporate service providers from Panama and Uruguay suggested that banks or service providers will undertake no risks for little money or if it’s an unknown new client. They will go so far as to ask about the colour of your underwear or the name and hobbies of your great-great-grandmother. However, for accounts in the millions or dollars, or referred by a current client, the situation is much different. These comments are somehow confirmed by an article published in the eve of automatic exchange of information. Swiss banks told Argentine clients they would close any account below USD $5 million. That’s right, the criteria to close an account was not suspicious activity or lack of supporting documents, but accounts with less than USD $5 million.

The investment industry had its own “Panama Papers” moment in 2014 (the Clearstream case), when the US found out that Iran was investing in US securities. However, as a response to these findings, Iran’s investments in US securities did not end, but they were simply hid behind one extra intermediary. Clearstream in the end had to pay USD $150 million, but the industry’s secrecy was not overhauled.

In this context, trusting banks and other intermediaries to police a trillion dollar industry without any public scrutiny poses a huge risk.

Proposals

Complete transparency may eventually be achieved through a global asset registry. In the meantime, out of all the possible assets that individuals or investment funds may hold, it is necessary to determine the ownership of all financial assets, including especially companies listed on a stock exchange.

To cross-check the information, or as a preliminary step, it is also necessary to identify the individual investors of all investment funds, given that they could be investing in financial assets or in real assets. For example, Blackstone alone reported to hold USD $250 billion in real estate. Christoph Trautvetter, who investigated real estate ownership in Berlin, described how it may be impossible to identify the investors behind these investment funds. On top of this, by investing in real estate through investment funds it is possible to pay less taxes than would be normally required if an investor owned a house under their own name.

Beneficial ownership transparency for the whole investment industry may sound too general a rule for intermediaries and types of investment funds that may be very different from each other. To put it simply, a hedge fund available only to high net worth individuals may pose much more illicit financial flows risk than a mutual fund or a pension fund for Californian teachers. The same could be true for any highly supervised institution. Hardly anything is more regulated than a bank, but still Odebrecht, Latin America’s largest construction group, managed to buy its own bank to undertake the global corruption scheme. Besides, the need for transparency makes no difference: as long as some types of funds or types of financial assets are excluded, it will not be possible to know who owns what and to detect cases of underreporting or double reporting. It would only be an invitation for abuse or other shenanigans. Criminals or anyone trying to remain hidden could set up an offshore company, “hire” investors or accomplices as “employees” and then create a fund for these “employees”. It would require many more resources to ensure that regulators all over the world are properly supervising the excluded funds.

A similar exemption could have been proposed for regular companies. After all, a company involved in procurement, with politically exposed persons (PEPs) or with offshore structures may pose more risks than a company owned by just one shareholder that is only involved in selling pizza. But beneficial ownership registries intelligently cover all companies, not those that “look suspicious” or risky. Therefore, the best solution is to avoid loopholes by requiring the same level of transparency for all funds.

Our paper describes different proposals, from the most ambitious and comprehensive (lowering beneficial ownership thresholds and identifying the beneficial owners of all financial assets, investment funds and all intermediaries involved in the ownership chain), to only identifying the beneficial owners of financial assets (without disclosing how they own them) or beneficial owners of investment funds (without disclosing which underlying securities they ultimately hold).

Given that interests in investment funds and in financial assets may be part of securities traded by algorithms where securities are held for just a few seconds, ownership could be reported as of the end of each business day.

Conclusion

Investment funds and financial assets involve many intermediaries, all with partial information, but ultimately holding and trading assets worth trillions of dollars. However complex and sophisticated the industry may be, there is one simple reality: neither the public nor the authorities have a full picture of all existing financial assets and who ultimately owns them, let alone whether they are paying the corresponding taxes or whether they are part of money laundering schemes.

This paper is set to start the conversation about what needs to be done to increase transparency in this highly relevant industry forgotten until now by beneficial ownership transparency.

All comments and feedback are welcome: [email protected]

[1] For example, the EU anti-money laundering directive defines beneficial owners of companies as: “the natural person(s) who ultimately owns or controls a legal entity through direct or indirect ownership of a sufficient percentage of the shares or voting rights or ownership interest in that entity, including through bearer shareholdings, or through control via other means, other than a company listed on a regulated market that is subject to disclosure requirements consistent with Union law or subject to equivalent international standards which ensure adequate transparency of ownership information.” (emphasis added); the UK guidance on beneficial ownership: “This guidance applies to those companies which are registered under the Act and to which Part 21A applies. As a result this guidance may be relevant to companies limited by guarantee, and unlimited companies as well as companies limited by shares. Part 21A does not, however, apply to certain companies, for example, those which are listed on a UK main or “regulated” market” (emphasis added); OECD’s Global Forum 2016 Terms of Reference: “A.1.1. Jurisdictions should ensure that information is available to their competent authorities that identifies the owners of companies and any bodies corporate.10 [Footnote 10. (Please note, however, exceptions for publicly-traded companies or public collective investment funds or schemes)]” (emphasis added).