The Financial Action Task Force (FATF) in charge of the Recommendations on Anti-Money Laundering and Combating the Financing of Terrorism (AML/CFT) has opened a consultation on the reform of Recommendation 24 on beneficial ownership for legal persons.

We have sent written submissions and participated at calls on Recommendation 24 and recently Recommendation 25 (on beneficial ownership for trusts and other legal arrangements). Now, the FATF is inviting feedback on their proposed amendments to the text of Recommendation 24.

You may find our proposed amendments below. If you have any comments or feedback, please write to [email protected]

In essence, here’s a summary of our proposals:

1) Application to all legal vehicles (eg trusts), not just to legal persons.

All changes to Recommendation 24 (asking for beneficial ownership registration, public access, etc) should also apply to trusts (which are currently covered and subject to less transparency under Recommendation 25). The main argument in favour of this equal treatment is two-fold. First, trusts are a type of complex legal vehicle subject to many types of abuses (and widely mentioned in the latest Pandora Papers leak) so they should be subject to even more transparency (or at least as much as) legal persons, not less. Second, private foundations share the same control structure and goals as trusts, and given that they are considered legal persons, they are already subject to Recommendation 24, so there’s no reason why trusts should be considered special or different.

2) Mandatory beneficial ownership registries (without alternative mechanisms)

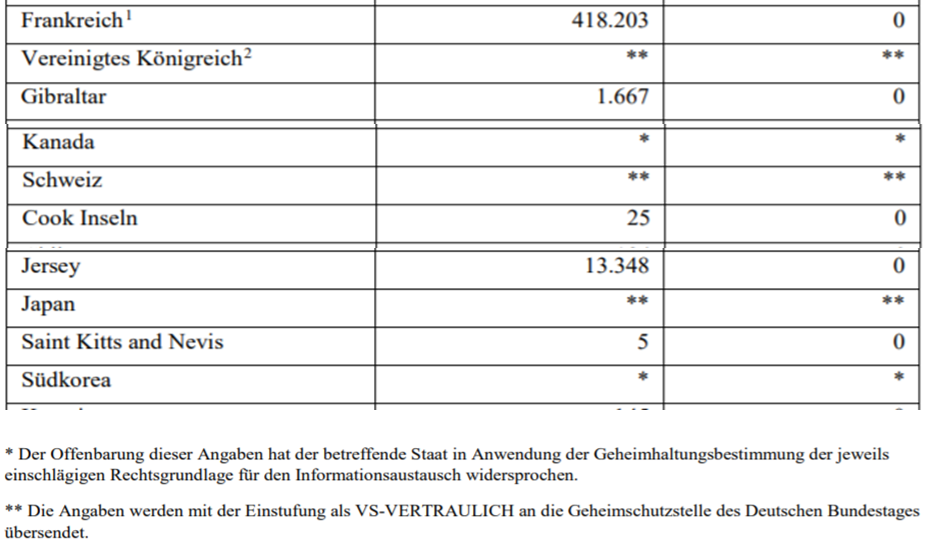

While a multi-pronged approach using many sources of information is welcome, a central beneficial ownership register should become mandatory for all countries, without allowing for “alternative mechanisms”. As of April 2020, mora than 80 jurisdictions already had laws requiring beneficial ownership information to be registered with a government authority. As of November 2021, that number is closer to 90 with new relevant countries such as the United States. Given that countries are already allowed to use any government authority, eg the commercial register, the tax administration, the financial intelligence unit, the central bank or a new beneficial ownership register, there is no need to water-down this requirement by allowing “alternative mechanisms”.

As for the cost of the registry approach, countries with low resources should consider that requiring beneficial ownership registration need not involve any new cost. The cheapest option is to add a field on beneficial ownership to the forms that must already be registered by local entities and taxpayers (eg incorporation form with the commercial register or a tax return with the tax administration).

3) Central registries

While countries should be allowed to have as many local registries as they need (eg for federal purposes) all information should be centralised in a digital platform. This central platform should contain information on beneficial ownership and for all types of legal vehicles, and ideally also legal ownership information to avoid consistency problems. This way, it will be possible to know all the legal vehicles related to a beneficial owner, no matter in which district or province this vehicle was incorporated. Likewise, by having information on all legal vehicles as well as legal and beneficial ownership in the same place, it will be possible to ensure consistency, to prevent cases where the beneficial ownership register describes that company A is owned by company B which in turn is owned by John, but the shareholder register states that company A is owned by trust X.

4) Verification independent from risk approach

Verification is a crucial element to ensure that beneficial ownership registries will be useful. While obliged entities (eg banks) and the general public (civil society organisations, investigative journalists) should be encouraged to report discrepancies or indicate on other red-flags, this should essentially be a responsibility of countries, not something that they should be able to outsource. In fact, the whole purpose of now reforming Recommendation 24 to require beneficial ownership registries is because the old approach (relying on banks as the source for beneficial ownership information) was proved insufficient. In other words, if banks were proven not to be effective as the only source for beneficial ownership information, it’s not possible to expect the verification can be effective, if only banks are required to do it. It should be governments’ role to ensure that registered beneficial ownership information is trustworthy.

In addition, reporting discrepancies should be one measure, but certainly not the only one. A criminal could have lied both to the registry and to the bank. In this case, there will be no discrepancy, but information will still be inaccurate. Verification should involve cross-checks, data validation and red-flagging.

With regard to applying verification based on a risk-based approach, one analogy may be relevant. Just as all passengers must go through airport security, all legal entities should be subject to verification mechanisms. Otherwise, verification would fail to identify the “unknown unknowns” as well as needing to catch up with an ever changing and sophisticated criminals. For instance, the UK had to widen the scope of beneficial ownership registration. First, for companies and limited liability partnerships (LLPs). Then, to Scottish limited partnerships after finding out that they were involved in major money laundering schemes. Now, there’s evidence that limited partnerships from England and Wales and Northern Ireland are increasingly being misused, so the UK should be required to subject them to beneficial ownership registration too. It would have been easier to cover all partnerships from the beginning.

A risk-based approach should be applied but only to determine which entities should be subject to enhanced verification procedures (eg filing additional documentation as part of registration, in-person meetings, etc). The risk-based approach should also involve publishing statistics on the typical structures of legal entities (number of layers, nationality of layers, type of entity of each layer, number of legal owners and beneficial owners and their nationalities and residencies) to determine outliers. Structures considered too complex compared to the “statistically” normal one, should also be subject to enhanced verification procedures.

5) Beneficial ownership registration for foreign legal vehicles with link to a country

Contrary to general practice, beneficial ownership registration should be required not just for locally incorporated legal vehicles (as is currently the case in most countries), but especially for any foreign legal vehicle which has a link to the country. These foreign legal vehicles may be creating illicit financial flows risks in the country (eg holding real estate or bank accounts as part of a money laundering scheme) and there may be no information about them in the beneficial ownership register. For this reason, links that would trigger beneficial ownership registration should be as comprehensive as possible:

(i) holding registrable or valuable assets (eg real estate, cars, ships, aircrafts, art work, etc),

(ii) having relations with an obliged entity (holding bank accounts, engaging with a lawyer, notary or accountant),

(iii) having operations in the country (eg providing or acquiring goods or services, including free services such as social media, streaming or other digital services),

(iv) having income or being considered tax resident or subject to tax, or

(v) having a local participant who is resident in the country, participating either as a legal owner, beneficial owner, director, trust party, etc.

6) Beneficial ownership definition and thresholds

The beneficial ownership definition should be based on the FATF Glossary, rather than on the customer due diligence rules of Recommendation 10. In essence, this means that a beneficial owner should be any natural person who meets at least one prong: ownership, control or benefit (rather than applying a cascading test where a person with “control via other means” is only considered a beneficial owner (second step) when no one is identified as having a “controlling ownership” (first step)).

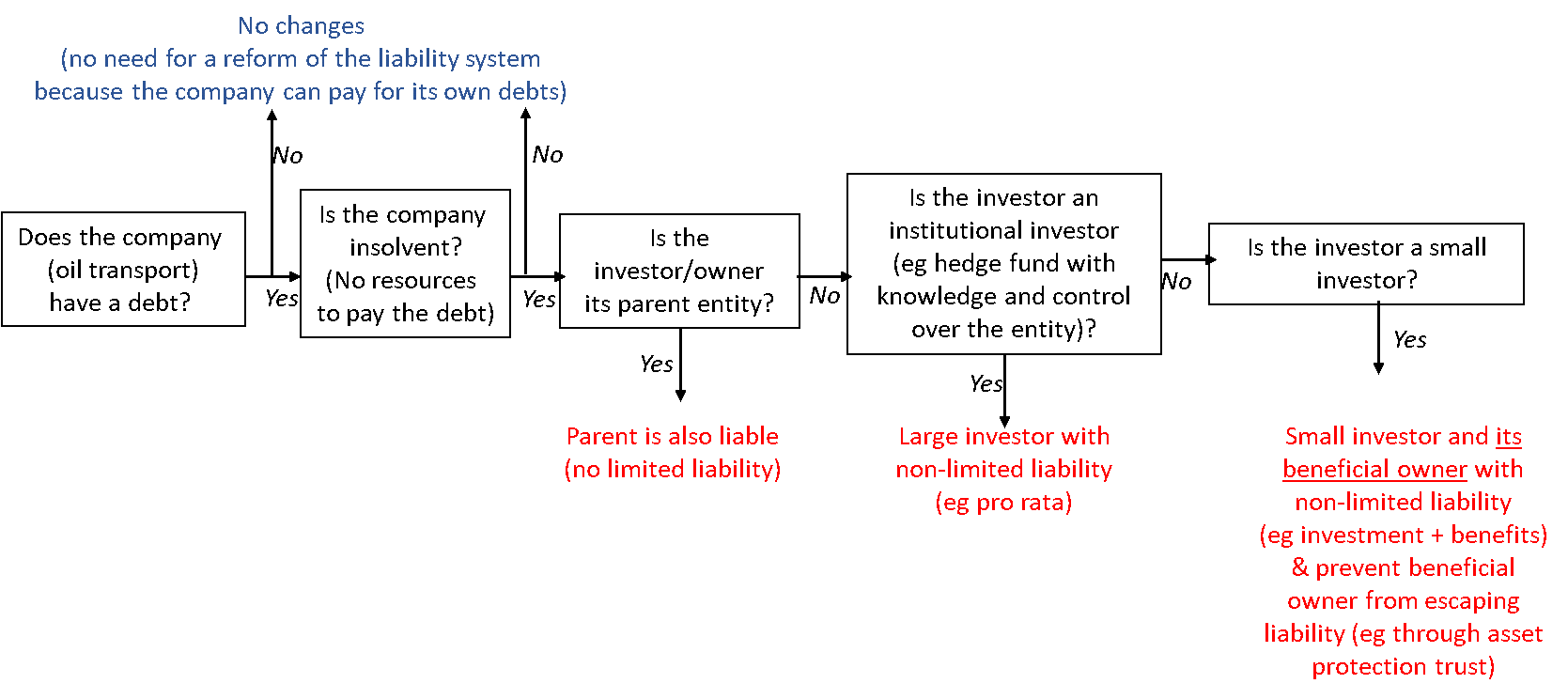

Thresholds should not be applied to the beneficial ownership definition for legal persons (just as it happens with legal ownership of companies and with beneficial ownership for trusts, where absolutely all shareholders and all parties to the trust must be identified, without any threshold). This means that any natural person who directly or indirectly holds one share, vote, interest or right to economic benefit in an entity should be registered as a beneficial owner. In addition, there cannot be cases where an entity doesn’t have a beneficial owner (so a senior manager would never be identified as a beneficial owner). Many countries apply a beneficial ownership definition without thresholds, including Argentina, Botswana and Ecuador.

Although the “25 per cent” threshold is too easy to bypass by having an entity with more than four shareholders, in reality any threshold can be circumvented. For instance, a recent Al Jazeera investigation revealed an enabler hiding the beneficial owner of a football club by incorporating an investment fund where the investors/shareholders were 21 companies (so that all companies would have a shareholding below 5 per cent, which was the threshold to report ownership to the financial regulator). An investigation by Kroll into the Moldova Laundromat revealed the same strategy to acquire a bank, by holding interests of up to 4.99 per cent, to be below the 5 per cent threshold.

7) Prohibition of bearer shares and warrants

Bearer shares should be prohibited. In a globalised and digital world, giving ownership to whoever holds a paper-share creates no benefit to society, but absolute secrecy. There is no reason why they should remain in existence, even if registered or immobilised. All pre-existing bearer shares should be converted into registered shares. In case of no-compliance, pre-existing bearer shares should be cancelled, losing all rights, without any chance to reinstate rights or obtain compensation (unlike the Swiss case).

Until full prohibition is established, countries which allow immobilisation should require a government authority (instead of a private party like a lawyer or bank) to immobilise the bearer shares.

Bearer warrants should also be prohibited, and financial instrument (eg call options, convertible debt, etc) should either be prohibited or disclosed as a beneficial owner (eg if John has convertible debt or a call option to acquire shares, he should be considered -and registered- a beneficial owner).

8) Prohibition of nominee shareholders and directors

Nominee shareholders, aka fake shareholders, and nominee directors should be prohibited. In a world with perfect beneficial ownership transparency, nominee shareholders would become obsolete because everybody would know who the nominator (beneficial owner) is. The prevalence of nominee shareholders means that current beneficial ownership transparency hasn’t reached an acceptable level. Nominee shareholders should thus be prohibited to remove an additional obstacle to transparency.

Given that de facto nominees may still be employed despite the prohibition, countries should establish, in addition to civil and criminal penalties, that registered information has “constitutive effect” (meaning that rights start to exist upon registration) so that the nominee would be entitled to all the economic and political rights over an entity. The nominator (real beneficial owner) would have no rights at all. This would work as an incentive not to register incorrect or inaccurate information.

Nominee directors should also be prohibited because they are an abuse of law (if the law considers necessary to have a number of directors, it makes no sense to appoint a person who only rubber-stamps decisions or forwards correspondence). To enforce this prohibition countries should disregard any indemnity provision in favour of directors and consider that directors should be held responsible for the entities they manage or direct, without being able to claim that they were merely nominees.

9) Public access

Public access to legal and beneficial ownership information should become the norm. Public access is available in EU countries, other European countries (eg the UK, Ukraine and the Western Balkans), as well as in countries in Africa (eg Ghana), Latin America (eg Ecuador) and Southeast Asia (eg Indonesia).

Given that legal vehicles give excessive benefits to their owners (eg limited liability, asset protection, possibility to hold assets and operate through the legal vehicle, etc), beneficial ownership transparency should be considered the minimum “consideration” (price) in exchange for creating legal vehicles and enjoy their benefits. Individuals who prefer not to have their names in public beneficial ownership registries should refrain from creating or owning legal vehicles, and should rather operate under their own name.

Public access is the best way to save resources for everyone. Those who need the information (local and foreign competent authorities, local and foreign obliged entities, etc) would have access to it without constraints. Those who hold the information would not need to spend time and resources to respond to requests for beneficial ownership information. Verification will be enhanced by increasing scrutiny by obliged entities, civil society organisations and investigative journalists.

Although some of the details may be restricted and available only to competent authorities, publicly accessible information should enable the determination of who a beneficial owner is (eg to determine if John Smith owning company A is the same John Smith owning company B) and the nature of such beneficial ownership (eg John is the beneficial owner because he has 100% of the votes).

Here are our proposed amendments to the Recommendation’s text (in italics and underlined is what the FATF is proposing to amend, and in bold is what we are proposing):

Recommendation 24. Transparency and beneficial ownership of legal persons vehicles, including legal persons and arrangements

Countries should assess the risks of take measures to prevent the misuse of legal persons for money laundering or terrorist financing, and take measures to prevent their misuse. Countries should ensure that there is adequate, accurate and timely up to date information on the beneficial ownership and control of legal persons that can be obtained or accessed rapidly and efficiently in a timely fashion by competent authorities through either a government register that holds of beneficial ownership information or an alternative mechanism. In particular, cCountries that have legal persons that are able to should not permit legal persons to issue new bearer shares or bearer share warrants, and take measures to abolish prevent the misuse of existing bearer shares and bearer share warrants. Countries, or which allow nominee shareholders or nominee directors, should prohibit take effective measures to ensure that nominee shareholders and directors they are not misused for money laundering or terrorist financing. Countries should consider measures to facilitate public access to beneficial ownership and control information by financial institutions and DNFBPs undertaking the requirements set out in Recommendations 10 and 22 as well as by foreign authorities and other stakeholders (eg civil society organisations and investigative journalists).

Interpretive Note to Recommendation 24 (Transparency and Beneficial Ownership Of Legal Persons Vehicles, including legal persons and arrangements)

1. Competent authorities should be able to obtain, or have access in a timely fashion to, adequate, accurate and current information on the beneficial ownership and control of companies and other legal persons (beneficial ownership information[1]) that are created[2] in the country, as well as those that have any present ML/TF risks and have sufficient links[3] with their country (if they are not created in the country). Countries may choose the mechanisms they rely on to achieve this objective, although they should also comply with the minimum requirements set out below. It is also very likely that cCountries will need toshould utilise a combination of mechanisms to achieve the objective.

2. As part of the process described in paragraph 1 of ensuring that there is adequate transparency regarding legal persons, countries should have mechanisms that:

a) identify and describe the different types, forms and basic features of legal persons in the country, publish statistics on the typical ownership and control structure of local legal persons, considering at least (i) number of layers, (ii) type of legal vehicle in each layer (eg company, trust, partnership, etc), (iii)nationality of layers, (iv) number of legal owners and beneficial owners and (v) their nationality and residence.

b) identify and describe the processes for: (i) the creation of those legal persons; and (ii) the obtaining and recording of basic and beneficial ownership information;

c) make the above information publicly available; and

d) assess the money laundering and terrorist financing risks associated with different types of legal persons created in the country, and take appropriate steps to manage and mitigate the risks that they identify.

e) assess the money laundering and terrorist financing risks associated with different types of foreign-created legal persons to which their country is exposed, and take appropriate steps to manage and mitigate the risks that they identify[4].

A. BASIC INFORMATION

3. In order to determine who the beneficial owners of a company[5] are, competent authorities will require certain basic information about the company, which, at a minimum, would include information about the legal ownership and control structure of the company. This would include information about the status and powers of the company, its shareholders and its directors and the full ownership chain and control structure up to each beneficial owner.

4. All legal persons (and arrangements) companies created in a country should be registered in a company registry[6] to have legal validity[7]. Whichever combination of mechanisms is used to obtain and record beneficial ownership information (see section B), there is a set of basic information on a company that needs to be obtained and recorded by the company[8] as a necessary prerequisite. The minimum basic information to be obtained and recorded by a company should be:

a) company name, proof of incorporation, legal form and status, the address of the registered office, basic regulating powers (e.g. memorandum & articles of association), a list of directors, legal entity identifier (LEI) and unique identifier such as a tax identification number or equivalent (where this exists); and

b) a register of its legal owners (shareholders or members or partners, or in the case of private foundations, all the parties including founder, member of foundation council, protectors, beneficiaries and any other individual with effective control over the private foundation), containing the names of the legal owners shareholders and members and number of interests shares held by each legal owner shareholder and categories of interests shares (including the nature of the associated voting rights).

5. The company registry[9] should record all the basic information set out in paragraph 4(a) above.

6. The company should maintain the basic information set out in paragraph 4(b) within the country, either at its registered office or at another location notified to the company registry. However, if the company or company registry holds beneficial ownership information within the country, then the register of shareholders need not be in the country, provided that the company can provide this information promptly on request.

B. BENEFICIAL OWNERSHIP INFORMATION

7. Countries should follow a multi-pronged approach in order to ensure that the beneficial ownership of a company can be determined in a timely manner by a competent authority. Countries should decide, on the basis of risk, context and materiality, what form of registry or alternative mechanisms they will use to enable efficient access to information by competent authorities, and should document their decision. This should include the following:

a) Countries should require companies to obtain and hold adequate, accurate and up-to-date information on the company’s own beneficial ownership and the full ownership chain and control structure up to each beneficial owner; to cooperate with competent authorities to the fullest extent possible in determining the beneficial owner, including making the information available to competent authorities in a timely manner; and to cooperate with financial institutions/DNFBPs to provide adequate, accurate and up-to-date information on the company’s beneficial ownership information.

b) (i) Countries should require adequate, accurate and up-to-date information on the beneficial ownership of legal persons to be held by a public authority or body (for example a tax authority, FIU, companies registry, or beneficial ownership registry). If information need not be is not held by a single body, the country should implement a digital platform to centralise legal and beneficial ownership information (including the full ownership chain and control structure) of all legal persons only[10].

b) (ii) Countries may decide to use an alternative mechanism instead of (b)(i) if it also provides authorities with efficient access to adequate, accurate and up-to-date BO information. For these purposes reliance on basic information or existing information alone is insufficient, but there must be some specific mechanism that provides efficient access to the information.

c) There should be no exemptions from beneficial ownership registration, unless the exact same information that is required to be registered is already available by another government authority, eg the stock exchange, central securities depository, etc. In such cases, the beneficial ownership register should contain a link or a duplication of the beneficial ownership information which is already available with the other government authority (eg the stock exchange).

Countries should use any additional supplementary measures that are necessary to ensure the beneficial ownership of a company can be determined; including for example information held by regulators or stock exchanges; or obtained by financial institutions and/or DNFBPs in accordance with Recommendations 10 and 22[11].

10. All the persons, authorities and entities mentioned above, and the company itself (or its administrators, liquidators or other persons involved in the dissolution of the company), should maintain the information and records referred to for at least five years after the date on which the company is dissolved or otherwise ceases to exist, or five years after the date on which the company ceases to be a customer of the professional intermediary or the financial institution.

TIMELY ACCESS TO ADEQUATE, ACCURATE, AND UP-TO-DATE INFORMATION

11. Countries should have mechanisms that ensure that basic information and beneficial ownership information (as well as the full ownership chain and control structure), including information provided to the company registry and any available information referred to in paragraphs 7, is adequate, accurate and up-to-date. Countries should require that is accurate and is kept as current and up-to-date as possible, and the information should be updated within a reasonable period following any change.

Adequate information is information that is sufficient to identify and determine the risk[12] of the natural person(s) who are the beneficial owner(s), and the means and mechanisms through which they exercise beneficial ownership or control.

Accurate information is information which has been verified to confirm its accuracy by verifying the identity and status of the beneficial owner using reliable, independent source documents, data or information. The extent of Enhanced verification measures may vary according to the specific level of risk.

Countries should consider complementary measures as necessary to support the accuracy of beneficial ownership information, e.g. discrepancy reporting, automated cross-checks against other databases, pre-filled forms, data validation mechanisms and requiring information to be verified by a liable obliged entity with physical presence in the country.

Up-to-date information is information which is as current and up-to-date as possible, and is updated within a reasonable period (e.g. within one month) following any change. Registered information should be considered to have “constitutive effect” where rights (to dividends, votes, etc) only exist for a legal or beneficial owner since registration.

12. Competent authorities, and in particular law enforcement authorities, should have all the powers necessary to be able to obtain timely access to the basic and beneficial ownership information held by the relevant parties, including rapid and efficient access to information held or obtained by a public authority or body or other competent authority on basic and beneficial ownership information, and/or on the financial institutions or DNFBPs which hold this information. In addition, countries should ensure public authorities have timely access to basic and beneficial ownership information on legal persons in the course of public procurement.

13. Countries should require their company registry to provide and/or facilitate timely access by financial institutions, DNFBPs and other countries’ competent authorities to the public information they hold, and, at a minimum, to the basic information referred to in paragraph 4 (a) above. Countries should also establish consider facilitating timely access by financial institutions and DNFBPs to information referred to in paragraph 4(b) above and to beneficial ownership information held pursuant to paragraph 7 above, as well as public access to these information legal and beneficial ownership information (which should include at least the full name, identifier, date and nature of beneficial ownership). Public access should be online, for free and in open data format.

D. OBSTACLES TO TRANSPARENCY

14. Countries should take measures to prevent and mitigate the risk of the misuse of bearer shares and bearer share warrants, for example by prohibiting the issuance of new bearer shares and bearer share warrants[13]; and, abolishing for any existing bearer shares and bearer share warrants, by applying one or more of the following mechanisms within a reasonable timeframe[14]:

(a) prohibiting them

(a) converting them into a registered form; or

(b) immobilising them by requiring them to be held with a regulated financial institution or professional intermediary, with timely access to the information by the competent authorities; and [Immobilisiation, if it is to be kept, should only be allowed by a government authority, eg the Central Bank or Central Securities Depository.]

(c) During the period before (a) or (b) is completed, requiring holders of bearer instruments to notify the company, and the company to record their identity before any rights associated therewith can be exercised.

15. Countries should take measures to prevent and mitigate the risk of the misuse of prohibit nominee shareholding and nominee directors. Examples to enforce this prohibition include:, for example by applying one or more of the following mechanisms[15]:

(a) applying the “constitutive effect” where registered legal owners or beneficial owners, even if proven to be de facto nominees, are to be considered the real owners of interests and rights to dividends or distributions, where the real (hidden) owner loses all rights over those interests, in addition to the civil, administrative and criminal consequences that apply against the nominee and nominator for violating the prohibition of nominee shareholdings requiring nominee shareholders and directors to disclose their nominee status and the identity of their nominator to the company and to any relevant registry, financial institution, or DNFBP which holds the company’s basic or beneficial ownership information, and for this information to be included in the relevant register as part of basic information; or

(b) considering nominee directors to be fully liable for the legal person’s actions, disregarding any indemnity provision or defence based on being a mere nominee requiring nominee shareholders and directors to be licensed[16], for their nominee status and the identity of their nominator to be recorded in company registries, and for them to maintain information identifying their nominator and the natural person on whose behalf the nominee is ultimately acting[17], and make this information available to the competent authorities upon request[18].

E. OTHER LEGAL PERSONS

16. In relation to foundations, Anstalt, Waqf[19], limited partnerships and limited liability partnerships, countries should take similar measures and impose similar requirements, as those required for companies (including beneficial ownership registration), taking into account their different forms and structures.

17. As regards other types of legal persons, countries should take into account the different forms and structures of those other legal persons, and the levels of money laundering and terrorist financing risks associated with each type of legal person, with a view to achieving appropriate levels of transparency. At a minimum, countries should ensure that similar types of basic information should be recorded and kept accurate and current by such legal persons, and that such information is accessible in a timely way by competent authorities. Countries should review the money laundering and terrorist financing risks associated with such other legal persons, and, based on the level of risk, determine the measures that should be taken to ensure that competent authorities have timely access to adequate, accurate and current beneficial ownership information for such legal persons.

E. LIABILITY AND SANCTIONS

1. 18. There should be a clearly stated responsibility to comply with the requirements in this Interpretive Note, as well as liability and effective, proportionate and dissuasive sanctions, as appropriate for any legal or natural person that fails to properly comply with the requirements. In addition to civil and criminal sanctions, the consequences for failing to register accurate or updated information must include:

a) for non-compliant legal persons: removal from the register and loss of legal existence (being prevented from owning assets or engaging in any transaction),

b) for non-compliant beneficial owners: loss of all rights (dividends, voting rights and their interest in the legal person),

c) for non-compliant legal owners who fail to identify their beneficial owners: loss of all rights (dividends, voting rights and their interest in the legal person),

G. INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION

19. Countries should rapidly, constructively and effectively provide the widest possible range of international cooperation in relation to basic and beneficial ownership information held by public authority or body, on the basis set out in Recommendations 37 and 40. This should include (a) facilitating access by foreign competent authorities to basic information held by company registries; (b) exchanging information on shareholders; and (c) using their powers, in accordance with their domestic law, to obtain beneficial ownership information on behalf of foreign counterparts. Countries should monitor the quality of assistance they receive from other countries in response to requests for basic and beneficial ownership information or requests for assistance in locating beneficial owners residing abroad. Consistent with Recommendations 37 and 40, countries should not place unduly restrictive conditions on the exchange of information or assistance e.g., refuse a request on the grounds that it involves a fiscal, including tax, matters, bank secrecy, etc. Information held or obtained for the purpose of identifying beneficial ownership should be kept in a readily accessible manner in order to facilitate rapid, constructive and effective international cooperation. Countries should designate and make publicly known the agency(ies) responsible for responding to all international requests for BO information.

[1] Beneficial ownership information for legal persons is the information referred to in the Glossary and should cover all natural persons that have either ownership, control or benefit from a legal person, without applying thresholds. interpretive note to Recommendation 10, paragraph 5(b)(i). Controlling shareholders as referred to in, paragraph 5(b)(i) of the interpretive note to Recommendation 10 may be based on a threshold, e.g. any persons owning more than a certain percentage of the company (determined based on the jurisdiction’s assessment of risk, with a maximum of 25%).

[2] References to creating a legal person, include incorporation of companies or any other mechanism that is used.

[3] Links should include at least: (i) holding registrable or valuable assets (eg real estate, cars, ships, aircrafts, art work, etc), (ii) having relations with an obliged entity (holding bank accounts, engaging with a lawyer, notary or accountant), (iii) having operations in the country (eg providing or acquiring goods or services, including free services such as social media, streaming or other digital services), (iv) having income or being considered tax resident or subject to tax, or (v) having a local participant who is resident in the country, participating either as a legal owner, beneficial owner, director, trust party, etc.

Countries may determine what is considered a sufficient link on the basis of risk. Examples of sufficiency tests may include, but are not limited to, when a company, on a non-occasional basis, owns a bank account, employs staff, owns real estate, invests in the stock market, owns a commercial/business insurance, or is a tax resident in the country.

[4] This could be done through national and/or supranational measures. These could include disregarding the legal effects of unregistered local or foreign entities, as well as prohibiting nationals and obliged entities from engaging with those unregistered local or foreign entities. requiring beneficial ownership information on some types of foreign-created legal persons to be held as set out under paragraph 7. [BO registration for linked foreign entities should be mandatory]

[5] Recommendation 24 applies to all forms of legal persons. The requirements are described primarily with reference to companies, but similar requirements should be applied to other types of legal person, taking into account their different forms and structures – as set out in Section E.

[6] “Company registry” refers to a register in the country of companies incorporated or licensed in that country and normally maintained by or for the incorporating authority. It does not refer to information held by or for the company itself.

[7] Unregistered legal persons and arrangements should be able to enjoy limited liability, hold assets under their name, enter into transactions with any party or engage with obliged entities.

[8] The information can be recorded by the company itself or by a third person under the company’s responsibility.

[9] Or another public body in the case of a tax identification number.

[10] A body could record beneficial ownership information alongside other information (e.g. basic ownership and incorporation information, tax information), or the source of information could take the form of multiple registries (e.g. for provinces or districts, for sectors, or for specific types of legal person such as NPOs), or of a private body entrusted with this task by the public authority.

[11] Countries should be able to determine in a timely manner whether a company has or controls an account with a financial institution within the country.

[12] Examples of information aimed at identifying the natural person(s) who are the beneficial owner(s) include the full name, nationality(ies), the full date and place of birth, residential address, national identification number and document type, and the tax identification number or equivalent in the country of residence. Additional details to determine the risk should include: other residencies and nationalities, PEP status, date since becoming a beneficial owner, value or nature of the transaction that allowed them to become a beneficial owner (eg acquiring 10% of the shares for a value of X).

[13] Or any other similar instruments without traceability such as financial instruments (eg call options, futures, etc).

[14] This requirement does not apply to bearer shares or bearer share warrants of a company listed on a stock exchange and subject to disclosure requirements (either by stock exchange rules or through law or enforceable means) which impose requirements to ensure adequate transparency of beneficial ownership.

[15] Countries may instead choose to prohibit the use of nominee shareholders or nominee directors. If so, the prohibition should be enforced.

[16] A country need not impose a separate licensing or registration system with respect to natural or legal persons already licensed or registered as financial institutions or DNFBPs (as defined by the FATF Recommendations) within that country, which, under such license or registration, are permitted to perform nominee activities and which are already subject to the full range of applicable obligations under the FATF Recommendations.

[17] Identifying the beneficial owner in situations where a nominee holds a controlling interest or otherwise exercises effective control requires establishing the identity of the natural person on whose behalf the nominee is ultimately, directly or indirectly, acting.

[18] For intermediaries involved in such nominee activities, reference should be made to R.22 and R.28 in fulfilling the relevant requirements.

[19] Except in countries where Waqf are legal arrangements under R.25.