In 2015 we set up a new website called Fools’ Gold, dedicated to investigating (and skewering) the woolly concept of “national competitiveness,” which is so widely (mis)used by many politicians, and so derided by many economists.

We are closing the Fools’ Gold site now, for operational reasons, but we’ll use it as an opportunity to re-publish some of the core elements from the site, notably a series of interviews or summarise reflecting the ideas of leading thinkers. The first comes from Martin Wolf, the chief economics commentator of the Financial Times and one of the world’s most influential economists. Wolf published a book in 2004, before the global financial crisis, called Why Globalization Works: the case for the global market economy. A forceful, heavily researched and uncompromising work, it became for a while a bit of a bible for those pushing for freer trade and further liberalisation of the global economy.

While we don’t agree with all parts of the book, we think that the chapter dealing with the idea of “national competitiveness” head on, is extremely good. Wolf told us in 2015, via email, that he has “changed his mind on finance” but stands by this particular chapter, entitled “Sad About the State,” which is the subject of today’s blog.

Optimistic about the state: Martin Wolf’s searing attack on the Competitiveness Agenda

By Nicholas Shaxson (originally published in 2015)

Few people who cited Why Globalization Works in defence of endless liberalisation and globalisation seem to have realised that this chapter, Sad About the State, contains a damning and clear-thinking critique of what is probably their most politically potent set of arguments for steamrollering opposition to liberalisation – what we like to call the ‘Competitiveness Agenda’.

This agenda is constantly pushed by lobbyists and hyperventilating politicians who yell that we are in a #globalrace (that is, for the non-twitterati, a ‘global race’) on things like tax and labour and environmental standards, and that our countries have no choice but to ‘compete’ by gratefully showering goodies and privileges on the owners of mobile capital, in terror that if we don’t feed them we become ‘uncompetitive’ and they will all skitter away to Geneva or Singapore.

Wolf asks what the word ‘competitive’ might mean for a

country – and we haven’t seen evidence that he has changed his mind

significantly about any of what follows here.

Introduction: the problem with ‘competitiveness’

Wolf’s arguments, exploring what it might mean for a country to be ‘competitive’, can be summed up briefly.

In short, he supports our own optimistic view that you

needn’t bow down to the competitiveness agenda. “Competitiveness”, he

explains, is Fools’ Gold – and in pretty much the same way that we argue it is. The chapter contains a related argument, which Wolf summarises:

“The notion of the competitiveness of countries, on the model of the competitiveness of companies, is nonsense.”

“The notion of the competitiveness of countries, on the model of the competitiveness of companies, is nonsense.”

He points out, as we often have,

that what so often lies behind all the woolly thinking out there is the

‘fallacy of composition’ (or, in his geeky formulation, the application

of “‘partial equilibrium’ reasoning to a ‘general equilibrium’

question.”) In other words, what’s good for one company or sector isn’t

necessarily good for the whole economy.

Wolf covers ground we’ve already explored recently via Paul Krugman and Robert Reich

– but he gives it a much more comprehensive treatment than either of

them, exploring a greater range of ways that one might talk about

competitiveness.

All of the possible tests for ‘competitiveness’ crumble to dust in his hands – as they should.

Part of our raison dêtre here at Fools’ Gold is to

expose and debunk exactly these commonly held arguments, and Wolf has

done a lot of heavy lifting for us here.

Must social democratic states bow before omnipotent markets?

The chapter “Sad about the State” begins by quoting the

English philosopher John Gray, who argued that “the chief result of this

new competition is to make the social market economies of the post-war

period unviable.” Similarly, Thomas Friedman famously said that the world is ‘flat’: every country in the world would have to become like the US or die.

Wolf points out that this is a view held on both the right

(beneficient markets force evil governments not to fleece their people)

and on the left (beneficient governments can’t shield their people from

nasty global forces). He summarises:

“Policies matter to the extent that they adversely affect performance. The notion of competitiveness is irrelevant.”

“Both agree that impotent politicians must now bow before

omnipotent markets. This has become one of the clichés of the age. But

it is (almost) total nonsense.”

And this is, if you think about it, a very optimistic view.

We like to put it this way: politicians think they

are in a global race (and thus feel obliged to slash taxes on capital,

weaken labour rights and so on) – but they are labouring under false

consciousness. A country can tax mobile corporations and protect workers – and suffer no overall economic penalty for

doing so. International co-ordination on these things is useful, for

sure, but another way is possible: countries can unilaterally opt out

of the race.

To engage can be to indulge in self-harm.

It is all about trade-offs. For example, a more ‘competitive’ (devalued) exchange rate may benefit exporters, but it will hurt consumers buying dearer imported goods. Is this an overall benefit? Perhaps; perhaps not. Corporate tax cuts benefit corporations, but the lost revenues hurt taxpayers elsewhere and consumers of public services. To call these moves a priori ‘competitive’ is silly. But people do it all the time. For example, the pre-eminent Oxford-based think tank advising the UK government on corporate tax policy, was apparently set up to give the UK a more “competitive” tax system. Wolf looks briefly at corporation tax, noting in passing that countries show a huge range of corporation tax as a share of GDP (then between 1.8 percent in Germany to 6.5 percent in Australia in 2000; today the range is 1.2 percent in Slovenia to 8.5 percent in Norway), without any obvious effect on growth despite this enormous sevenfold range.

As a first general source of reassurance about unstoppable

global forces, Wolf notes that there are large swathes of the economy

sheltered from global forces: immovable domestic services, healthcare

and education, for instance. (This seems to correspond to what the

Manchester Capitalism project formerly known as CRESC calls the ‘Foundational Economy’.)

And the sheltered parts of the economy are huge: in most high-income

countries, Wolf says, relatively non-tradable services like this amount

to two thirds of GDP or more. No need to get ‘competitive’ here.

But not all of the economy is thus sheltered, so at least

in theory, there might still be something to talk about. In which

case, how might one measure ‘competitiveness’?

Possible measures of ‘competitiveness’

Wolf looks at a number of possibilities. His basic test candidates in Why Globalization Works are highly taxed and regulated European countries, versus lower-tax and more laissez-peers like the U.S. and the U.K.

“Are there any signs that the higher-tax countries are, in some sense, uncompetitive?”“Competitiveness would turn out to be a funny way of talking about productivity.”

– Paul Krugman

And what could ‘uncompetitive’ actually mean?

Wolf’s first test looks at the work of Belgian economist Paul de Grauwe, who studies “competitiveness rankings” from the World Competitiveness Report from the IMD in Lausanne, and relates these to ratios of social security spending in GDP. Wolf summarises:

“He finds a modest positive correlation: the higher the

social security spending, the more competitive the country. It is not

difficult to understand why this positive correlation might exist: a

generous social security system increases people’s sense of security and

so may make them more willing to embrace change.”

This clearly isn’t in line with the urgings of the Competitiveness Agenda. But

still, the objection to these rankings, Wolf says, is that they are

arbitrary. “Can we obtain more direct indicators of competitiveness?

Yes.”

So, second, he cites possible weak trade

performance (or trade deficits) as another possible meaning of

‘uncompetitive.’ But the ‘competitive’ UK and US economies, he noted,

were running trade deficits, while the highly taxed countries ran

surpluses (and this overall picture hasn’t changed decisively for the Eurozone, the UK or the US since then.)

So trade performance isn’t where ‘competitiveness’ is at, either.

Third, could it be all about export growth, relative to the local markets?

Well, exports from all the highly taxed economies grew

faster than their markets from 1993-2002, while low-tax Japan and the US

performed badly. (Latest data

suggests that the UK and low-tax Japan have performed relatively poorly

here; France and Germany have done rather better, and the US has done

quite well – which isn’t so surprising for a faster-growing population.)

This is a mixed bag: still no obvious overall pattern.

Fourth, could it be ‘the share of exports in the

world economy’ that we’re after? He looks at the numbers (we haven’t yet

found an updated data set for this,) and finds that all the main OECD

countries saw a modestly declining share, presumably because other

exporters like China are growing fast. He concludes “there is no sign of

an exceptional deterioration in the trade performance of the highly

taxed and regulated continental European countries.”

So it’s not that either.

“Tax revenue does not go up in smoke. It is spent on things.”

He then summarises that“a slightly less

economically illiterate way of assessing ‘competitiveness’ is in terms

of flows of capital and labour. “A high-tax economy might bleed capital,

for example, particularly corporate capital.”

This could possibly be measured, fifth, through

examining the current account, he says. A country bleeding capital will

have a capital account deficit, (which by definition is the same as a

current account surplus.) He finds a motley assortment of performances

in the highly taxed and regulated European area and an overall tiny

current account surplus there (which doesn’t seem to have

changed much since, except in the last couple of woeful Euro-years,

overshadowed by Grexit fears). No obvious smoking gun here either.

Sixth, a related point, what about a more pointed

measure: net capital outflows as a proportion of savings? In other

words, what proportion of national savings was exported abroad in a

given year? Euro countries tend to save more than the US or UK, he

notes, so are more likely to be able supply the capital cravings of

their Anglo-Saxon peers by investing some of their savings over there.

But even after some exports of capital there, he found that the European

countries invested domestically as much, if not more than, the US, as a

share of GDP:

“There is, in other words, no sign of de-capitalization or capital flight from highly taxed continental European countries.”

Seventh: capital flows are a blunt instrument

anyway: what about a more pointed measure, namely large net outflows of

foreign direct investment (FDI), pointing to an ‘uncompetitive’ economy?

Again, he finds a mixed bag in the Eurozone, with one outlier as the

worst performer on this measure: the United Kingdom, with a very large

net stock of FDI abroad of nearly 33 percent. Wolf’s comment:

“What is striking is the variety of national positions.

There is no sign that highly taxed countries, in general, suffer from a

huge, unrequited outflow of corporate capital.”

Latest UNCTAD data, p209 shows this:

|

$trn, 2013 |

Inward FDI stock |

Outward FDI stock |

Net |

% of GDP |

|

USA |

4.9 |

6.4 |

1.5 |

9.0 |

|

UK |

1.6 |

1.9 |

0.3 |

11.5 |

|

EU |

8.6 |

10.6 |

2.0 |

10.8 |

Still no obvious pattern that could suggest a loss of ‘competitiveness’ for highly-taxed European nations.

Having been through these seven possibilities, all of which fell to pieces under cross-examination, he concludes:

“Lack of competitiveness is nowhere to be found in these

highly taxed countries. Particularly important is the finding that they

are not suffering a haemorrhage of capital or skilled people. Being rich

and stable, with superb social services, they are net importers of

people”

And, despite all the shrieking and anecdotes about high taxes and regulations driving clever people away, the more recent evidence seems to bear Wolf out, as numerous studies have found. Sure, the Eurozone’s had problems of late, but these things go in cycles, and the US and UK haven’t recently been looking so clever. “How is this possible? How can some countries have much higher tax and regulatory burdens than others and yet show none of the signs of a lack of international competitiveness?.”

Some better measures?

The story doesn’t end there, though. Wolf offers what he sees as more defensible models for ‘competitiveness’.

“The question, then, is whether the notion of

competitiveness of countries, under globalization, has any relevance.

The answer is that it does, but in very different ways from those

popularly supposed. Two legitimate meanings can be identified: changes in the terms of trade – the relation between the prices of exports and imports; and overall economic performance. Neither is what those worried about competitiveness mean.”

So he examines these two meanings.

First, terms of trade.

An improvement in the terms of trade means that a

country’s exports are becoming more valuable: in short, the country can

buy more imports with the same level of exports. But if an improvement

in the terms of trade means imports are becoming relatively cheaper,

then people will cry: “we are being flooded with cheap imports! We are

becoming uncompetitive!” Wolf summarises:

“The paradox of the popular debate is that improvements in

competitiveness, thus defined, are generally seen as a deterioration

instead. The availability of cheaper imports, which improves the terms

of trade, is seen as a reduction in competitiveness.”

This is a tricky argument to make, of course: French

workers thrown on the dole by cheap Chinese imports won’t be

mollified by cheap trinkets for them to put in their kids’ Christmas

stockings. But Wolf’s overall point here is not invalidated by that, and

it returns us to the fallacy of composition: the performance of the

export sector isn’t the same as the performance of the whole economy.

Second, overall economic performance. Here, his point is quite simple.

“Many of those who think of competitiveness mean overall

economic performance: productivity, employment and growth. These are

perfectly legitimate objectives of policy. There is no question that the

level of taxation and regulations, as well as the quality of public

services, have an impact on economic performance. But this impact does

not come via anything that might be called ‘competitiveness.’ ”

(Remember Krugman’s point about ‘competitiveness’ simply

being ‘a funny way of talking about productivity.’) And here the

laissez-faire UK currently looks particularly problematic: Britain’s

“Open for Business” government, obsessed with winning the “global race”

with “competitive” policies, has presided over the weakest productivity record of any government since the Second World War. (The U.S. has a less disappointing, but still lacklustre, record.)

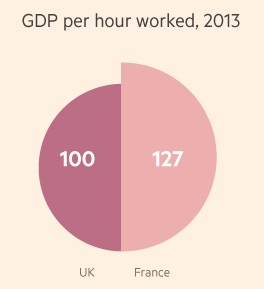

Would it be cheeky of us to point out that, as the FT noted

in March, French productivity, in terms of GDP per hour worked, was a

whopping 27 percent higher than in the UK? See this chart from that FT

story:

We’ll restrain ourselves, of course, from saying that the French

economy is much more competitive than Britain’s – France’s unemployment

rate is currently quite a bit higher – but still.

David Ricardo: it’s the trade offs, stupid

Wolf’s discussion of ‘competitiveness’ ranges still further.

He makes an extended foray into David Ricardo’s theory of comparative advantage, a concept that is also clearly relevant for connoisseurs of national ‘competitiveness’.

“The

notion that countries compete directly with one another, as companies

do, is nonsense. It is nonsense because the most important source of

both wealth and comparative advantage, namely people, is highly

immobile.”

In short, Ricardo said that gains from trade outweigh

losses, regardless of whether the trading partner is more or less

economically advanced, as each nation shifts its production to where it

has a comparative advantage. There are plenty of problems with Ricardo’s battered old theory, of course, but it’s not irrelevant. Let’s bear with Wolf here:

“A country cannot lose its comparative advantage. Its

comparative advantage can change. It is even possible that this change

is, in some sense, undesirable. But a country has to have a comparative

advantage in something.”

All that is needed, he argues, is that the relative prices

of different goods and services differ from their relative prices in

world trade. These differences, he adds, are greater than they ever were

in world history. What is more, the logic of comparative advantage

“would apply even if a given factor of production (such as

capital) were perfectly mobile, provided the distribution of some other

factors of production (natural resources, social and human capital or

knowledge) varied across countries and so generated sources of

comparative advantage.”

The big difference between countries, in this respect,

comes in the form of social and human capital: well-educated workers,

for instance. And people generally don’t move:

“Not only is the human population anchored; so,

notwithstanding all the hyperbole about globalization, is the vast bulk

of its capital. People who live in stable, propserous countries believe

their investments are safest at home.

. . . .

[financial]

capital, the most mobile of all factors of production, will

flee from a jurisdiction so under-taxed that it fails to provide decent

and reliable justice.

. . . .

Capital will also be attracted by a jurisdiction with a highly educated labour force or any other complementary asset.

. . .

Because resources, particularly people, are immobile, patterns of comparative advantage are also deeply rooted.”

He could have noted more explicitly, as the Tax Justice Network has done,

that genuine productive capital that is embedded in the local economy

creating jobs and supply chains – the useful stuff, in other words –

isn’t generally tax-sensitive: investors are generally most interested

in other factors like education and infrastructure and the rule of law.

And if it is tax-sensitive (which a fair amount of capital

admittedly is) then by definition it’s flighty, and therefore not

embedded, so it’s almost certainly the least useful stuff:

profit-shifting and other nonsense. Tax may affect the real stuff, but

only at the margin.

To illustrate this better, take the case where industries

are most locally rooted: mineral-rich countries, where the resources are

physically anchored underground. As OPEC learned in the 1970s, host

countries can apply exceedingly high tax rates and strong regulations,

and the investors will still come. They have to, because that’s where

the oil is. Tax cuts for Big Oil won’t increase ‘competitiveness’ in any meaningful way.

Yet natural resources aren’t a special case either, as Wolf explains.

“It is also true of activities that take advantage of

human skill, or cultural assets: German or Swiss engineering is an

obvious example.”

Even in finance, one of the most weightless of all sectors, clustering effects can be particularly strong, anchoring activity to big financial centres. And Wolf notes:

“It

is perfectly possible for countries to have high taxes and regulatory

standards, but no loss of international competitiveness.”

“because these foundations are location-specific, they can, within reason, be taxed.”

Even Ireland, supposedly a poster child for ‘competitive’

policies on corporate tax, supports Wolf’s, rather than the

‘competitive’ tax-cutters’ case, as we have shown.

Overall, then much of the analysis here seems to make

perfect sense. Countries don’t behave like companies. And showering

goodies on one sector of the economy, paid for by other sectors, doesn’t

seem like an obvious route towards anything one might sensibly call

‘competitiveness.’

Some quibbles

There is, of course, plenty in this otherwise fascinating chapter that one might disagree with.

Wolf makes a number of statements that he may well have

changed his mind about since the crisis, such as “minimum wages normally

reduce employment” which doesn’t seem borne out by recent evidence. He also makes an ill-advised brief foray into the hilarious world of Charles Tiebout,

and opines that open capital flows may provide useful ‘discipline’ for

corrupt governments: something that seems strange in light of the record

of élites in poor countries using ever freer global finance to loot

their nations and stash their wealth offshore and out of sight.

Wolf also understates the difficulties of taxing companies in the digital economy. This is important, because he conveys a sense that the battle is, if not won, not so hard to win. Yet even then he avoids the ‘tax competitiveness’ nonsense that has gripped so many nations like the UK. His response to the thorny problem of tax avoidance isn’t to recommend corporate tax cuts but instead to try and tax corporations more effectively — he even advocates something at the cutting edge of tax advocacy these days, called formula apportionment (a component of unitary taxation. (The Tax Justice Network prefers the term ‘tax wars‘ instead of ‘tax competition” and in an email exchange last year with today’s blogger, Wolf said “I don’t object to your rephrasing.”) He also takes a deft and hefty swing (not in this book, but more recently in the FT) at Britain’s ridiculous tax ‘domicile’ rules: it’s an attack that is firmly in line with his ‘competitiveness’ views from 2004. This one is particularly timely as Britain goes to the polls where the domicile rule has been a point of contention.

A last word

In short, this was (and still is) a devastating attack on

those who argue in terms of a need for countries to be ‘competitive’. So

it is an attack on one of the most politically resonants arguments used

in defence of the whole liberalising, tax-cutting project.

But at the end of the day, Wolf didn’t quite say it like this. Instead, he puts it like this:

“Politicians insist they have no choice: globalization

makes slashing taxes, cutting spending, reducing regulations and so on

inescapable. But this is a dishonest excuse for pursuing the right

policies. Worse, it is a dangerous one.”

If has since changed his mind on some of the reasons why

he thought the policies were right, then his searing critique of

politicians doing these things for the wrong reasons is all the more

powerful now.

But we would frame this all a slightly different way.

1. The Competitiveness Agenda is a nonsense: and thus potentially a house of cards.

2. Even so, this nonsense has politicians the world over

in its thrall. (Once you know where to look for it, you’ll find the

Agenda everywhere, larded into all sorts of rankings and phrases such as “Open for Business” or “a Competitive Tax System,” or “healthy business climate” and other weasel terms.)

3. The solution to false consciousness is to expose it. If

it is a house of cards, then it should be possible in the long run to

defenestrate it and turn its fevered advocates into laughing stock.

And that is, in short, why we have set up this site.

The basic arguments needed to demolish this cracking

edifice are already out there and have been for years, in the works of

people like Wolf, Krugman and others. But they are not getting through

where it matters.

What we think is needed now to combine expertise with

activism: pushing these woolly-minded arguments directly back in the

faces of those who wield them, and challenging them in public to stand

up and defend the indefensible.

We haven’t yet really got around to the activist phase yet: we’re building up our materials for now. But watch this space.

From Martin Wolf, “Why Globalization Works,”Yale Nota Bene 2005; particularly its chapter “Sad about the State.”