admin ■ Brexit and the future of tax havens

This week the Tax Justice Network’s John Christensen spoke at this event at the European Parliament organised by the European Free Alliance of the Greens on Brexit and the future of tax havens. Here’s more information on the event and you can watch the whole thing here. John spoke on the impact of Brexit on tax evasion and money laundering, offering up some important recommendations on how the EU should move forward in its treatment of the UK, its satellite havens and the City of London. Here are the notes he spoke from, and the accompanying slides.

BREXIT AND THE FUTURE OF TAX HAVENS

The Impact of Brexit on Tax Evasion and Money Laundering

22nd January 2019

It will come as no surprise that at the time of the 2016 referendum the UK government did not have a clear vision of the type of relationship for trade in financial services they would be seeking with the EU27 once Brexit is finalised.

The initial assumption seems to have been that passporting rights could be retained for the UK-based financial services sector and extended to satellites in the crown dependencies and overseas territories. This was the message I heard in the summer of 2016 both in London and the Channel Islands.

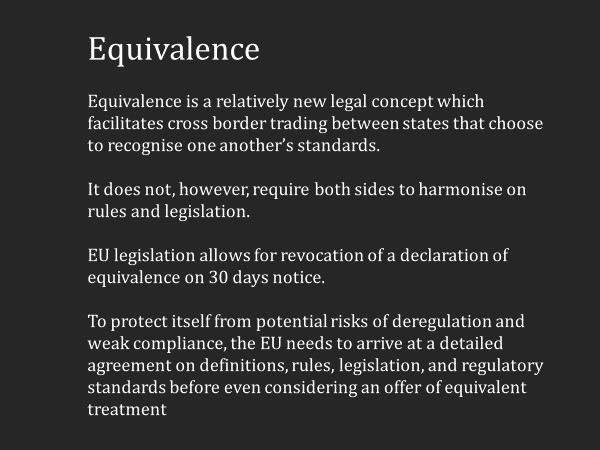

However, once it had become clear by end-2016 that passporting would not be a viable option, the focus shifted to gaining acceptance of mutual recognition of regulatory standards on the basis of equivalence.

Judging from discussions I’ve had this month in London, this expectation of recognition of equivalence of standards remains the goal for post-Brexit relations.

I am going to suggest that granting of equivalence should be contingent on the UK and its dependencies committing to and implementing minimum standards on transparency and regulatory compliance, and these commitments are subject to regular – annual – review of their spillover impacts on EU and other third-party states in order to block the UK from engaging in tax wars and regulatory competition.

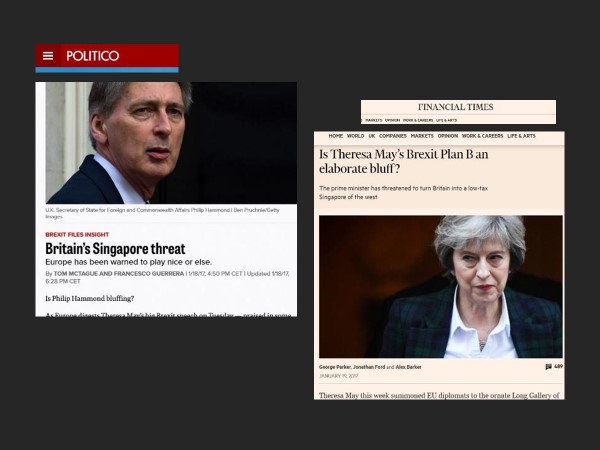

Before discussing this further, I want to raise my concerns about the UK government’s proposals for a Singapore-on-Thames.

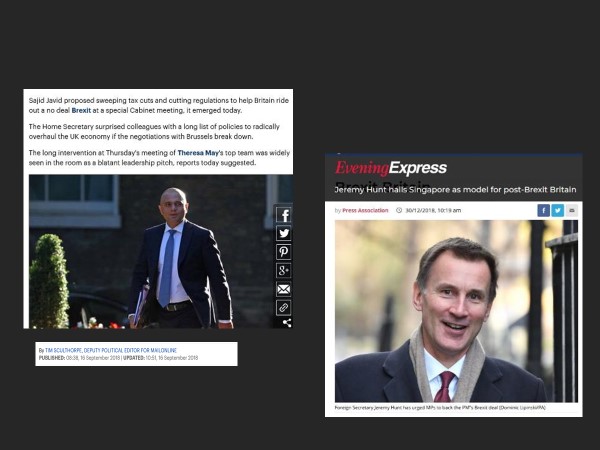

Senior government ministers have been signalling the Singapore-on-Thames development strategy since January 2017, when Prime Minister May and her Chancellor Philip Hammond both flagged it up as a potential route. Since then other senior ministers, including Foreign Secretary Jeremy Hunt and Home Secretary Sajid Javid, have signalled that this is the model they would pursue post-Brexit.

Just to put this in context, Singapore has rapidly expanded its role as an offshore financial centre in the past decade, currently ranks number five on the Financial Secrecy Index, and has a secrecy score of 67. That secrecy score reflects general weaknesses in Singapore’s corporate transparency regime and low level of commitment to tackling corporate tax dodging.

So this raises questions about what senior politicians in London mean when they talk about Singapore-on-the-Thames. Mr Javid – a serious contender to replace Theresa May as leader of the Conservative Party, who has worked as a banker in Singapore – has spoken about using tax cuts and deregulation as part of a “shock and awe strategy” to transform the post-Brexit UK economy.

What the Singapore-on-the-Thames visionaries appear to have in mind can be summed up as:

- A commitment to sweeping tax cuts for corporations and mobile rich people – tax wars as a fiscal weapon;

- Tax measures such as accelerated capital allowances to attract mobile investments to UK;

- Comprehensive de-regulation, removal of social and environmental protections;

- Weak or non-existent compliance with international anti-money laundering measures;

- Retaining golden visa arrangements to provide residence rights of wealthy non-British citizens, increasing exposure to oligarchs and corrupt illicit financial flows.

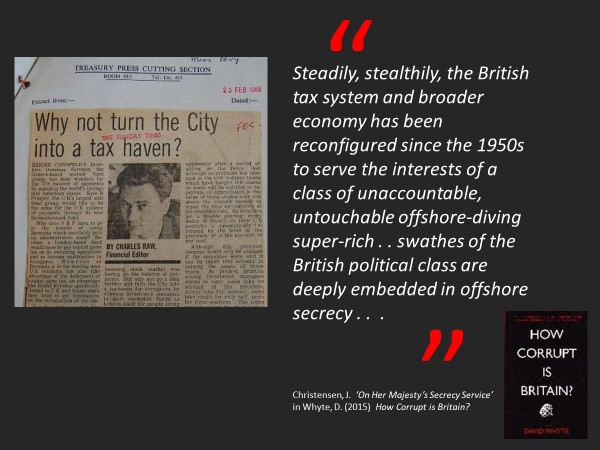

Of course, none of this is new. The UK set out down the route of becoming a major tax haven economy in the 1950s, and has pursued this development strategy under governments of all complexions.

The scale of the risks that tax haven Britain already imposes on other countries is revealed by a recent spillover analysis conducted by a research team comprising Professor Andrew Baker (SPERI) and Professor Richard Murphy (City University). These risks include:

- The use of “competitive” cutting of the corporate income tax rate to the lowest among G20 countries, accompanied by favouring of territorial taxation which encourages profits shifting to tax havens, patent box arrangements, relaxed controlled foreign company rules, special facilities to encourage location of company treasury operations in tax havens:

- The UK’s (non) domicile rule which undermines the CIT and PIT tax bases of other countries by making Britain an attractive haven for high and ultra high net worth individuals;

- Notwithstanding the commitment to making company ownership information available on public registry, the Companies House registry is under-resourced and the available information is frequently inaccurate, out of date, and incomplete. This presents a major barrier to investigation.

- Company and trust administration practices in the UK and its tax haven dependencies threaten the integrity of third party country tax regimes because they (a) fail to accurately identify the beneficial owners of companies, (b) don’t comply with or enforce delivery of accounting data, and (c) don’t require adequate disclosure of company trading data;

- In practice British arrangements undermine the tax regimes of other countries by not requiring companies that are incorporated in Britain, but which claim to trade in third party countries and not in the UK, to submit annual tax returns. This creates a blind spot in international information exchange processes which deprive revenue authorities of other countries of vital information;

- Crucially, Britain continues to sustain a spider’s web of satellite tax havens and secrecy jurisdictions which act in a vertically integrated way to block information exchange processes and undermine international cooperation on tackling money laundering.

Looked at in isolation, the UK appears to be relatively transparent and fit for cooperation in anti-money laundering and anti-tax evasion programmes. But this is something of a Potemkin village: yes, the UK has committed to an open public registry of beneficial ownership of companies, but in practice the information available from Companies House is frequently out of date, inaccurate and consequently useless. Compliance across the entire financial services sector is weak, reflecting an under-resourced and fragmented regulatory service.

Among the many things revealed by the Panama and Paradise Papers leaks, it should be clear to everyone that British territories like the British Virgin Islands, Cayman, and the Channel Islands are intimately linked to the UK through commercial, legal and political ties. They even boast about these ties in their promotional literature. Collectively the provide a complex and evolving ecosystem of laws, regulations and (non)compliance, which undermines transparency and regulation across the world.

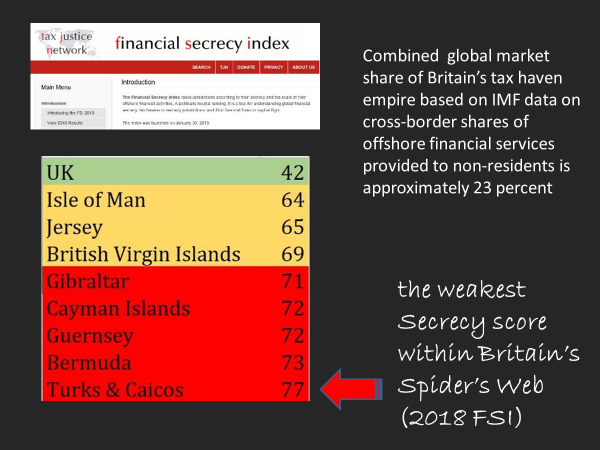

At the Tax Justice Network we consider the UK and its dependencies as a single entity, with London sitting as the voracious spider at the centre of a secrecy web which spans the globe. Our financial secrecy index reveals that this web is not uniform in its provision of secrecy to non-resident clients. While the UK appears relatively transparent in terms of laws and regulations, the majority of its satellites have secrecy scores which fall into the red zone, making them highly vulnerable to abuse by tax evaders and money-launderers.

This range of scores does not happen by accident. London likes to do its dirty business elsewhere, providing plausible deniability for its bankers, officials and politicians.

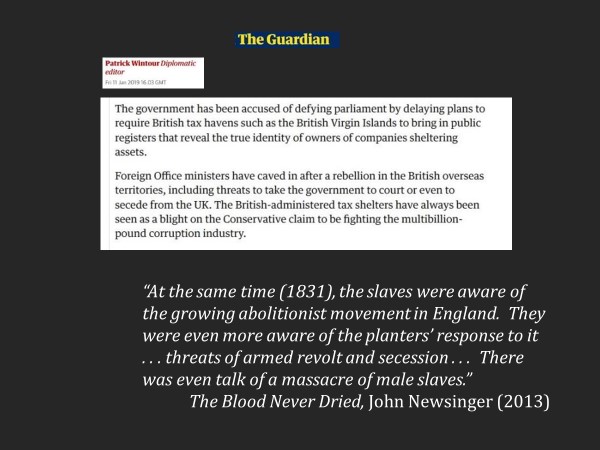

Despite all the promises to be transparent and cooperative, Britain’s offshore secrecy jurisdictions have resolutely refused to make their company registries open to public scrutiny, and some have even threatened to secede if this is forced upon them.

Shamefully, these threats of secession have a historical echo; during the period of huge public campaigning to end Britain’s slave economy in the early C19th, some of the same Caribbean territories currently resisting anti-money laundering measures also threatened to secede in order to protect the interests of their slave plantation owning elites.

This month the UK Government has delayed plans to implement a parliamentary decision to require these British territories to make ownership publicly available.

This is why we argue that Britain’s tax haven empire should be treated as a single entity and judged on the score of its lowest common denominator, currently the Turks & Caicos Islands with a secrecy score of 77 out of 100.

This approach provides a realistic assessment of Britain’s progress towards tackling tax cheating and money-laundering.

On this basis Britain and all of its secrecy jurisdiction territories should be included on the European Union’s blacklist and on every other tax haven blacklist.

So what is to be done in the context of Britain’s imminent withdrawal from the European Union?

The implication of the Prime Minister’s threat of a Singapore-on-the-Thames strategy is that London will continue with its weak anti money-laundering regime and its support for offshore secrecy in order to attract dirty money from all corners of the world.

Its satellite secrecy jurisdictions will continue to resist measures to strengthen international cooperation and make offshore companies and trusts more transparent. And the UK government will be complicit with this refusal to cooperate.

In such circumstances, it seems foolhardy for the European Union to grant financial service providers in London equivalent treatment to providers who operate within the Single Market and are regulated under the common rulebook. Put simply, this gives the fox full access to the hen house.

Therefore the first of my two principal recommendations is that the European Union should commission a comprehensive spillover analysis of the external risks posed by the British tax haven empire taken as a single entity.

This spillover analysis should be conducted by experts independent of any political influence, and its remit should be to provide an assessment of potential threats to the integrity of EU member states on the basis of the weakest points across the entire British spider’s web. In other words, look behind the greenwash of domestic laws in the UK itself and make an assessment on the basis of what international law firms, banks and accounting practices can do in territories like Bermuda, Cayman and the Turks & Caicos.

This spillover analysis should inform any decision by the EU regarding the recognition of equivalence of regulation. Until such time as the UK government requires all of its dependencies to fully adopt transparency standards (e.g. public registries of beneficial ownership), recognition of equivalence should be withheld and London-based banks and law firms should be required to operate within the Single Market on the basis of having commercial establishment subject to regulatory oversight by an EU Member State (in compliance with WTO rules on services falling under the mode 3 arrangements).

My second recommendation relates to the taxing of multinational companies. The threat of a post-Brexit UK government accelerating the race-to-the-bottom on tax rates and special treatments is clear and imminent. This can only worsen the rise of inequality and the undermining of the capacity of democratic states to protect their citizens.

The EU must therefore proceed with its Common Consolidated Corporate Tax Base project and move towards an apportionment-based approach for allocating profits to the countries where they are genuinely.

But establishing a common standard for the tax base will not protect individual member states from the predatory actions of a potential spoiler state committed to a Singapore-on-the-Thames strategy. The common tax base will need to be underpinned by an agreed minimum rate, say 25 percent, to block the race-to-the-bottom tactics adopted by tax havens.

The threat of a post-Brexit Singapore-on-the-Thames places Europe at a point in its political evolution at which it must choose between committing to deeper cooperation, for example on setting a common corporate tax base underpinned by a minimum tax rate, or whether to follow through on the current race-to-the-bottom trajectory, which will inevitably further erode national tax bases and regulatory, leading to slower growth, increased financial market volatility, deeper inequality and social division.

Thanks for your attention.

21st January 2019

Related articles

Bled dry: The gendered impact of tax abuse, illicit financial flows and debt in Africa

Bled Dry: How tax abuse, illicit financial flows and debt affect women and girls in Africa

9 December 2025

‘Illicit financial flows as a definition is the elephant in the room’ — India at the UN tax negotiations

Democracy, Natural Resources, and the use of Tax Havens by Firms in Emerging Markets

The millionaire exodus myth

10 June 2025

The Financial Secrecy Index, a cherished tool for policy research across the globe

Do it like a tax haven: deny 24,000 children an education to send 2 to school

Tax Justice transformational moments of 2024

The State of Tax Justice 2024

Question. In the case of a hard brexit can the UK remove the EUs anti avoidance directive from its statutory law all together?