John Christensen ■ Brexit, Pound Sterling, and the Finance Curse

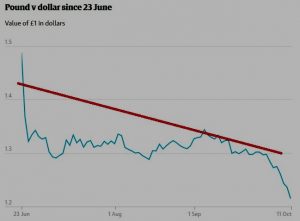

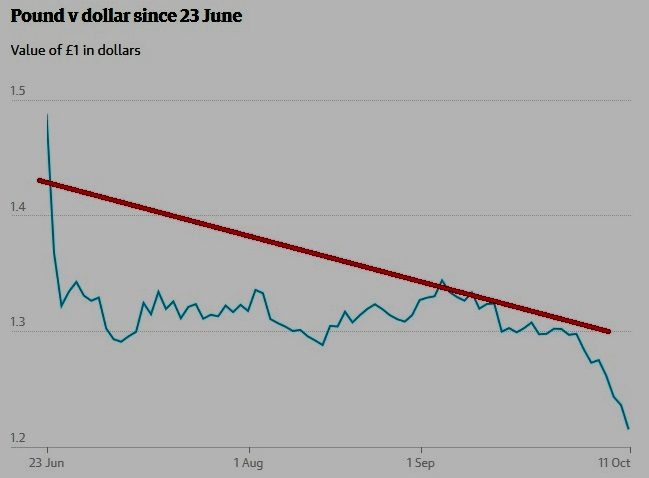

The significant fall in the value of the pound Sterling since the Brexit vote is likely to increase retail price inflation in Britain in the coming year. Many low income households will suffer steep rises in their costs of living. But in the long run might Sterling’s decline help rebalance the UK’s economy, which is burdened with an over-sized financial sector and increasingly geared towards being a tax haven for the world’s rich and powerful?

TJN’s John Christensen and Nick Shaxson have long argued that Sterling has been over-valued for decades, harming the real productive economy while boosting the City of London. They cite the City as an example of what they term the Finance Curse, a Political economic phenomenon comparable to the Resource Curse which afflicts mineral and oil and gas exporting economies. Contradicting the entrenched orthodoxy that what is good for the City is good for Britain as a whole, Christensen, Shaxson and Duncan Wigan have argued that hosting the City has harmed Britain’s development:

“The accelerated rise of finance in recent decades has damaged Britain’s alternative economic sectors, as productive activity cedes ground to financial rent extraction. Many of the harms, in cause and effect, are similar to those of a widely studied Resource Curse afflicting mineral-rich countries. Under the Resource Curse rents are extracted from the earth – but under the Finance Curse rents are extracted from the economy and society more broadly.”

Evidence of what are known as the Dutch Disease effects of Sterling’s over-valuation can be seen in Britain’s current account and trade deficits, both of which have worsened significantly in recent years. As Simon Head notes in an article, ominously titled The Death of British Business:

“The UK has long depended on heavy flows of investment from abroad to make up for the weaknesses in its own corporate and financial institutions. In 2015 the UK ran a deficit in its external trade in goods and services of 96 billion pounds ($146 billion in 2015), or 5.2 percent of GDP, the largest percentage deficit in postwar British history and by far the largest of any of the G-7 group of industrialized economies.”

Evidence of rent-seeking can be seen in the ways in which large global financial institutions, including banks, pension funds, hedge funds have been able to overcharge their clients, and extract subsidies through being ‘too-big-to-fail’. As economists Gerald Epstein and Juan Antonio Montechino argue in their recent study of financial services in the United States:

“These mechanisms (for overcharging) include the monopoly or oligopoly power of large banks in important financial sub-markets; overly complex, non-transparent financial products that allow financial institutions to overcharge and underperform; government subsidies that allow banks to borrow funds at subsidized rates from investors who believe they are ‘too-big-to-fail’; and a lax monetary and regulatory environment that allows finance to operate with too much leverage and too little capital at risk, thereby generating asset bubbles that feed both outsized financier income and dangerous instability.”

Epstein and Montechino’s analysis of the US economy applies to the UK economy, with extra bucketloads of adverse outcomes. These include state capture at least as great as that Wall Street imposes on the Hill; the criminalisation of Britain’s banks to the extent that Bill Black, a leading criminologist in the U.S. describes London as the “financial cesspool of the world”; and a long term preference on the part of banks to direct lending towards the property markets and short term trading in highly liquid assets.

Productivity is arguably the key crisis facing the UK economy, which by most measures has one of the lowest productivity levels amongst major economies. We would cite this as evidence of how the Finance Curse has afflicted Britain by lowering investment in infrastructure, training, research, and developing technologies of the future. The combination of a passive state tradition and a financial sector obsessed by short term returns has starved the economy of the long term investment needed to boost productivity. In this context a Sterling depreciation is unlikely, by itself, to be sufficient to improve productivity and achieve the desired boost to exports.

The question is whether Sterling’s decline will be sufficient in the longer term to induce a reverse of the Finance Curse by boosting investment in non-financial exporting sectors and attracting more high flying graduates away from the massively over-rewarded jobs in the City. An alternative scenario suggested by Simon Wren-Lewis in a recent blog is that the British government succumbs to the overweening political influence of the financial sector (itself an important feature of the Finance Curse) and pampers the City with further tax cuts and de-regulation.

Most economists are agreed about the short term inflationary impact of Sterling’s post-Brexit fall. Britain is a major importer of goods and services and the currency shift has caused a serious deterioration of the terms of trade between Britain and most of the rest of the world. In theory, the changed terms of trade should boost the export sectors – including the City of London – but it takes a long time for investment-starved export non-financial sectors to rebuild productivity and expand market share at a time when global demand is highly constrained by weak consumer demand. To make matters worse, uncertainty over access to the EU’s single market, especially for financial services suppliers who will need a ‘passport’ to ply their wares across the single market, has seriously impacted investor confidence.

The passport issue is a potential nightmare for the City. Even before the Brexit vote the European Commission and major Eurozone governments were pushing for banks trading in Euro denominated bonds and securities to do this business in financial centres where the Euro is the domestic currency. That excludes London. With the UK at the table, the City was able to resist these pressures. Brexit changes that political dynamic, leaving London (and its satellite tax havens in the Channel Islands) highly vulnerable to regulatory changes adopted in Brussels. To give some idea of the scale of this vulnerability, according to newly released data from Britain’s Financial Conduct Authority, approximately 5,500 UK registered companies, mostly engaged in financial services, depend on EU passport rights and stand to lose them as a result of Brexit.

Former IMF Deputy Director Ashoka Mody argues that Sterling’s fall might be a blessing in disguise. He agrees the regressive impact of the short term inflationary effect, but shares TJN’s view that the over-sized City of London has created an unbalanced economy (and an overpriced currency) to the immense disadvantage of most other industries – real estate being an exception since so much inwards investment heads into the property markets of London and other major metropolis. As Mody notes:

“The banking-property complex has been a parasite on the British economy, creating pathologies of financial vulnerability and exchange rate overvaluation.”

Indeed. And we would argue that the pathologies run deeper since overdependence on a single sector leads to state capture, constant lobbying to remove the social protections needed to protect citizens from corrupt financial practices, and path dependence on a mobile industry – financial services – which is largely rent-seeking in its outlook and short-termist in its actions.

It suits the City and its property-owning clients to boost Sterling’s value in order to attract offshore investment into the UK property market, which has become another must-have asset class alongside artworks and luxury yachts in the investment portfolio of the high net-worth class of global investors. Yet at some stage in the near future the latest UK property market bubble will inevitably pop, probably causing financial market crisis on at least the same scale as the 2008 collapse. The uncertainty caused by Brexit may well have brought that inevitable collapse forward, further exposing the structural weaknesses of the UK economy.

At this stage it is impossible to predict how long Brexit uncertainty will dampen investment and the value of Sterling. Some argue it might take as long as a decade for the dust to settle. A lot can be achieved over that period towards rebalancing the British economy. The focus of infrastructure investment can move away from the capital towards the regions which host productive sectors. Research and development funding can be boosted to attract more graduates away from the financial services. Property market inflation could be abated by adopting a land value tax and dropping subsidies to the buy-to-let owners. The City’s speculative impulses could be dampened by raising capital adequacy requirements and applying a financial transactions tax. Labour productivity could be boosted through investment in training and applying a living wage across all sectors (which would also reduce the huge wealth transfers from taxpayers to employers whose underpaid staff are forced to rely on housing benefits).

None of this is likely to happen, however, without an activist state willing to pursue a development strategy that will require a significant pruning back of Britain’s over-sized financial services sector and its role as the world’s largest tax haven. This will require a sharp and politically courageous break from a development strategy that has placed tax haven London and its spiderweb of offshore secrecy jurisdictions at the very heart of the British economy.

Like Wren-Lewis, we fear that the City, and its cheerleaders within the government, will react to the Brexit fallout by demanding further subsidy (tax cuts and deregulation, underwritten by the too-big-to-fail compact), and key policymakers will shy away from the long, hard slog of tackling the Finance Curse. For this reason, we share Wren-Lewis’ conclusion that it remains “hard to see any silver lining in the Brexit decision.”

With thanks to Andrew Baker at SPERI for comments and suggestions

TJN’s work on the Finance Curse is part of a wider EU funded research programme, Enlighten, looking at slow-burn crisis in the European Union

Related articles

The Financial Secrecy Index, a cherished tool for policy research across the globe

New Tax Justice Network podcast website launched!

Como impostos podem promover reparação: the Tax Justice Network Portuguese podcast #54

Convenção na ONU pode conter $480 bi de abusos fiscais #52: the Tax Justice Network Portuguese podcast

As armadilhas das criptomoedas #50: the Tax Justice Network Portuguese podcast

The finance curse and the ‘Panama’ Papers

Monopolies and market power: the Tax Justice Network podcast, the Taxcast

Tax Justice Network Arabic podcast #65: كيف إستحوذ الصندوق السيادي السعودي على مجموعة مستشفيات كليوباترا

Remunicipalización: el poder municipal: January 2023 Spanish language tax justice podcast, Justicia ImPositiva