John Christensen ■ Research shows UK’s Finance Curse grip tightening in next five years

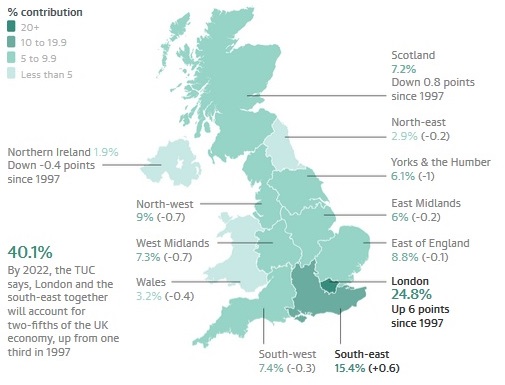

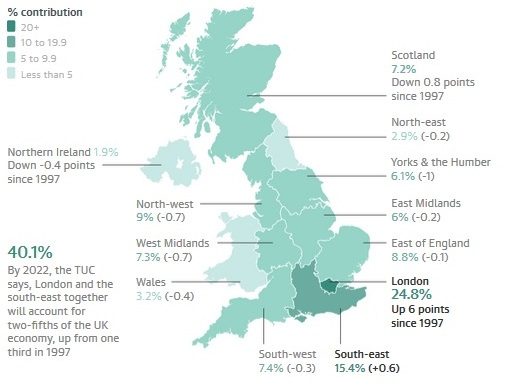

Britain’s Trade Unions Congress has published projections showing the increasingly unbalanced growth of the UK economy. As you can see from this map, economic activity is skewed in the direction of England’s south-east region, which includes London. It’s forecast to produce 40.1 percent of the UK’s gross domestic product by 2022. Given the importance of the City of London’s offshore financial centre to the region, this is a vivid demonstration of the Finance Curse in action.

In their original analysis of the Finance Curse, TJN’s John Christensen and Nicholas Shaxson argued that the rise and rise of the City of London from the 1970s onwards was a significant (though not the only) factor behind the dramatic decline in British manufacturing. The root causes of this decline can be found in a number of inter-related economic factors:

- First, the huge inflows of foreign capital into the City (much of it destined for mergers and acquisitions and real estate purchase rather than new investment) has served to prop up the pound Sterling, raising prices (look at UK property price inflation since the 1970s) and making it harder for other exporting sectors to compete on the global markets. This exchange rate/inflation effect is similar to the Dutch Disease that resource-dependent countries suffer from.

- Second, high salaries in the financial sector have a ‘brain drain’ effect, attracting a large proportion of university graduates away from other sectors of the economy and forcing those other sectors to compete against the highly inflated remuneration packages offered by banks and law firms in London.

- Third, oversized financial service sectors are prone to damaging cycles of rapid growth followed by bust. According to economist Hyman Minsky, periods of apparently stable growth in asset values breed complacency among lenders and borrowers, leading to rising debt leverage followed by crash. Debt is a major contributor to this volatility, which has worsened in recent decades as a result of the trend towards lax regulation.

During boom periods the harm caused by a dominant financial sector is disguised by the debt-fuelled growth in consumption. When busts occur the long-term damage caused to other sectors of the economy becomes more apparent, but those sectors are hard to resuscitate, not least because of skills shortages and long-periods of under-investment (known to development economists as ‘path dependence’).

This ratcheting effect is illustrated by the UK’s development over the past 20 years. In 1997 London and the south-east region contributed 33 percent of national output. This had risen to 38 percent by 2015, and is projected to contribute over 40 percent by 2022. Every other region of the UK is expected to decline relative to London and the south-east between now and 2022 (see the map above), by which time London will be contributing one quarter of national output.

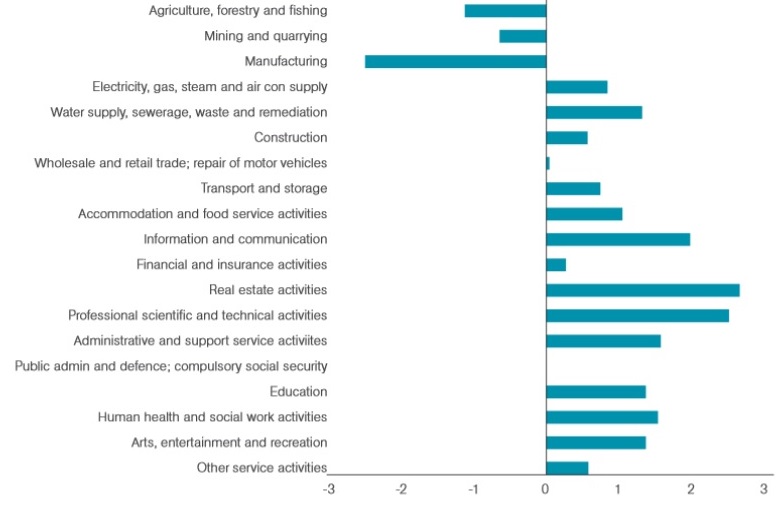

This chart below from the Institute for Public Policy Research indicates the scale of industrial restructuring in the UK economy. Major non-finance trading sectors (e.g. agriculture, manufacturing) have declined year-on-year- since 1992, while non-tradeable sectors (look at real estate) have risen dramatically. This pattern of restructuring is similar to what has been observed in resource-dependent countries.

Now, many politicians and City lobbyists will want to use this evidence of dependence on offshore financial services as an excuse for further increasing the policy bias towards the capital. Even more concessions will be granted to ‘Tax Haven GB’ (think Theresa May’s Singapore-on-the-Thames development threat), and an ever higher proportion of infrastructure spend will be oriented towards the capital, as is the case with the proposed HS2 high-speed rail link between London and Birmingham which will most likely suck skilled labour and consumption expenditure southwards.

But we would argue that a development strategy based on increasing dependence on the City’s offshore finance sector will exacerbate an already unsustainable situation. The outcomes will include slower growth and more crowding out of other industries, a continuation of the brain drain accompanied by weak job creation in downstream sectors (largely in the ‘gig economy’), rising inequality and low levels of human development, and a tendency towards state capture and authoritarianism. As Christensen, Shaxson and the Copenhagen Business School‘s Duncan Wigan concluded in their 2016 paper on Britain and the Finance Curse:

” . . under the Finance Curse rents are extracted from the economy and society more broadly. in the face of long term stagnation, historically low productivity levels, an elusive search for growth, huge public and private debt overhangs, and ever greater natural and social precacity, the time is ripe to consider new paths.” (the full paper is available here)

The map at the top of this blog provides stark warning of a worsening imbalance of the UK economy. Successive governments have waxed and waned in their enthusiasm about targeting sectoral diversification and spatial distribution of industrial activity (Prime Minister May has recently been criticised for merely “tolerating” the much vaunted ‘Northern Powerhouse’ strategy of her predecessor), but we would argue that any development strategy that aims to rebalance the UK will need to begin with a significant downsizing of the City of London.

Read Christensen and Shaxson’s ‘The Finance Curse’ publication, available here in PDF format or Kindle format.

Related articles

The Financial Secrecy Index, a cherished tool for policy research across the globe

New Tax Justice Network podcast website launched!

Como impostos podem promover reparação: the Tax Justice Network Portuguese podcast #54

Convenção na ONU pode conter $480 bi de abusos fiscais #52: the Tax Justice Network Portuguese podcast

As armadilhas das criptomoedas #50: the Tax Justice Network Portuguese podcast

The finance curse and the ‘Panama’ Papers

Monopolies and market power: the Tax Justice Network podcast, the Taxcast

Tax Justice Network Arabic podcast #65: كيف إستحوذ الصندوق السيادي السعودي على مجموعة مستشفيات كليوباترا

Remunicipalización: el poder municipal: January 2023 Spanish language tax justice podcast, Justicia ImPositiva