This year’s edition of the Financial Secrecy Index 2020 – our biennial ranking of the world’s biggest supplies of financial secrecy – has received more news coverage and global support than any previous editions of the index. With over 700 news articles and broadcast pieces published on the index in the past two weeks across 80 countries, it is clear that tackling financial secrecy has become an important issue to people around the world. More people are recognising the harmful impact rampant tax abuse by the ultra-rich and powerful has on their lives and want their governments to do something about it.

But perhaps, one of the best indicators of the success of the Financial Secrecy Index is the increasing hostility it receives from representatives of secrecy jurisdictions ranking high on the index. The first edition of the Financial Secrecy Index was published in 2009 so we at the Tax Justice Network have become familiar with the boilerplate responses from secrecy jurisdictions to our research. However, this year’s responses have been particularly aggressive: Luxembourg’s Finance Ministry called the index “misleading, if not often outright false”. We have been accused of making assumptions “without providing enough clear and credible evidence to support [our] analysis.” Cayman’s Ministry of Financial Services has said “TJN’s methodology remains flawed”. The UK’s Financial Secretary to the Treasury has said our research is “bogus”, except for the parts that criticise the legacy of the opposition party.

The most aggressive and coordinated attack on the Financial Secrecy Index, however, has unsurprisingly come from the Cayman government and Cayman Finance (the association of the financial services industry of the Cayman Islands). On the same day that our Financial Secrecy Index 2020 went live and ranked the British Overseas Territory, Cayman as the world’s biggest supplier of financial secrecy, the EU blacklisted Cayman as a non-cooperative jurisdiction. These two developments without a doubt have raised serious concerns for the territory and more broadly the rest of the UK’s network of secrecy jurisdictions (the UK spider’s web), particularly in this post-Brexit era.

After publishing a statement saying “TJN purposefully uses outdated, inaccurate and irrelevant information to manipulate the results of its report”, Cayman Finance then chased journalists who had published articles about the index to persuade them of the supposed inaccuracy of our research, and when that failed to yield success, resorted to promoting their tweets about the index.

As before, however, the attacks and responses have not identified any actual inaccuracies in the research or the calculations behind the index, and most are in the form of sweeping accusations. But in light of the coordinated efforts we’ve seen this year to target journalists and our Twitter followers with misinformation, and to misdirect scrutiny away from secrecy jurisdictions, we’ve prepared this blog to debunk some of the common claims used by secrecy jurisdictions to excuse their ranking on the index.

Claim 1: The Financial Secrecy Index unfairly targets or penalises jurisdictions with “successful” financial service industries.

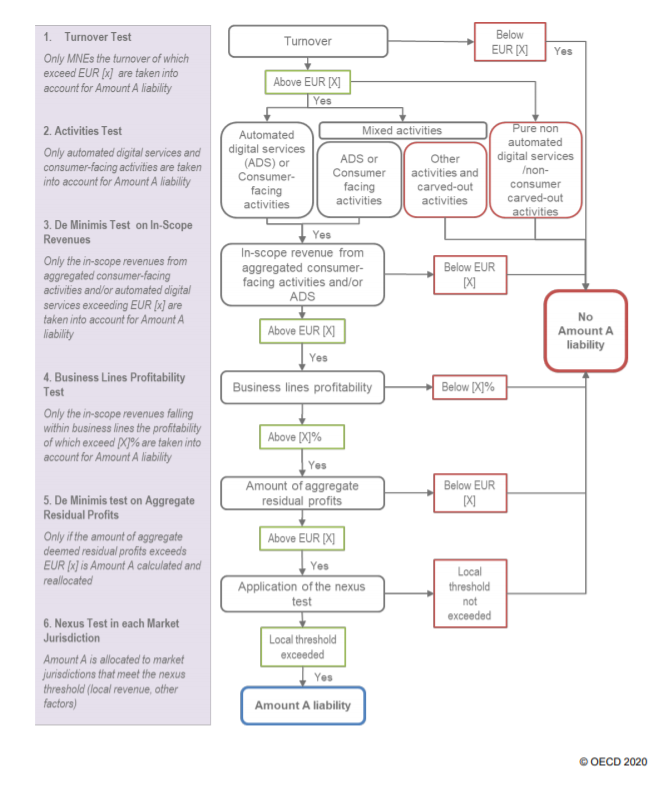

The Financial Secrecy Index ranks countries not on how secretive their financial laws are, but on how much financial secrecy they supply to non-residents outside of the country looking to hide their finances from the rule of law. This is done by grading each country’s legal and financial system with a secrecy score out of 100 where a zero out of 100 is full transparency and a 100 out of 100 is full secrecy. The country’s secrecy score is then combined with the volume of financial activity conducted in the country by non-residents to calculate how much financial secrecy is supplied to the world by the country.

This means a highly secretive jurisdiction that provides little to no financial services to non-residents, like Samoa (ranked 86th), will rank below a moderately secretive jurisdiction that is a major world player, like Japan (ranked 7th). The point is that a highly secretive jurisdiction used by no one, does less damage than a moderately secretive jurisdiction used by many people around the world.

Secrecy jurisdictions often twist this analysis on its head, claiming they are being treated unfairly for “successfully” attracting money from non-residents. Because they can sometimes have lower secrecy scores than some of the jurisdictions which they rank above, they claim the index purposefully ignores more secretive jurisdictions and targets jurisdictions with bigger financial services industries. Cayman Finance made this claim in their statement, saying “the TJN’s weighting system penalises countries with successful financial services industries.” The Cayman government then repeated this claim verbatim in subsequent responses.

The UK’s Financial Secretary to the Treasury similarly argued that the reason the UK ranks so high on the index despite having a lower secrecy score than countries like Brunei and Liberia is due to a “fudge factor”. He argues, “In its list of 133 jurisdictions, we [the UK] supposedly come 12th in terms of offensiveness, yet near the bottom we see Brunei, Vanuatu and Liberia. Is anyone seriously suggesting that this country is a less robust and effectively transparent tax jurisdiction than those?”

These claims miss the central purpose of the Financial Secrecy Index’s ranking of countries by their supply of financial secrecy as opposed to the secrecy of their financial laws: All countries have a responsibility to safeguard against financial secrecy. The more financial activity a country seeks to pull in from other countries’ residents, the greater the responsibility that country has to make sure its financial sector is not abused by people to evade or avoid tax in other countries or to launder money they’ve obtained elsewhere through illegal means.

To illustrate the point, imagine if Samoa, which is ranked 86th and has a secrecy score of 75, and Luxembourg, which is ranked 6th and has a secrecy score of 55, became fully transparent. Which country’s change in secrecy would make a much bigger impact on the world? Hint: only one of these countries has had a global financial scandal named after them.

And anyway, if Luxembourg actually becomes fully transparent, it would get a secrecy score of zero, which would rank it at the bottom of our index, no matter how big its financial centre is. So the size of a financial centre is neither good nor bad, but when combined with the secrecy score, its level of responsibility for illicit financial flows and other global ills is well reflected.We want to see reforms in the big financial centres like Switzerland, Cayman, the US, Luxembourg, Singapore and Hong Kong: only if they became more transparent, there would be a significant impact in the fight against crime and illicit financial flows.

To answer the UK’s Financial Secretary to the Treasury directly: no, we are not ‘suggesting’ that the UK is less transparent than Vanuatu. In fact, the objectively verifiable criteria of the secrecy score provide powerful evidence that the UK is more transparent than Vanuatu – on which, well done. But the UK’s global importance means that its moderate secrecy poses a much, much higher risk to the world of facilitating tax abuse and other corruption. We would welcome improvements in Vanuatu’s secrecy; but the UK’s scale of activity brings with it great responsibility. And that is why the UK’s backsliding has seen it move up to 12th in the index, as a jurisdiction of very substantial concern.

Claim 2: We are complying with global standards on transparency.

Secrecy jurisdictions often claim in response to their ranking on the Financial Secrecy Index that they are complying with, or have committed to comply in the future with, international standards on transparency and are therefore transparent. In some cases, secrecy jurisdictions claim that the index does not take these standards into account. In other cases, secrecy jurisdictions, claim that their compliance with international standards is proof that the Financial Secrecy Index does not provide an accurate assessment.

For example, Luxembourg has claimed “…the analysis (and concomitant ranking) fails to take into account the fact that regulators and institutions of the Luxembourg financial centre are applying all the relevant EU and international standards. Luxembourg…has implemented and put in practice all applicable OECD and EU rules”. Gibraltar has similarly argued that it “complies with all global standards” and is “at the forefront of transparency and global standards in this field”. The Cayman government argued, “The Cayman Islands’s standards of transparency are based upon recognised global standards. Unfortunately, the TJN’s methodology remains flawed, as does their definition of regulatory standards, which are not recognised by any global standard setting body.”

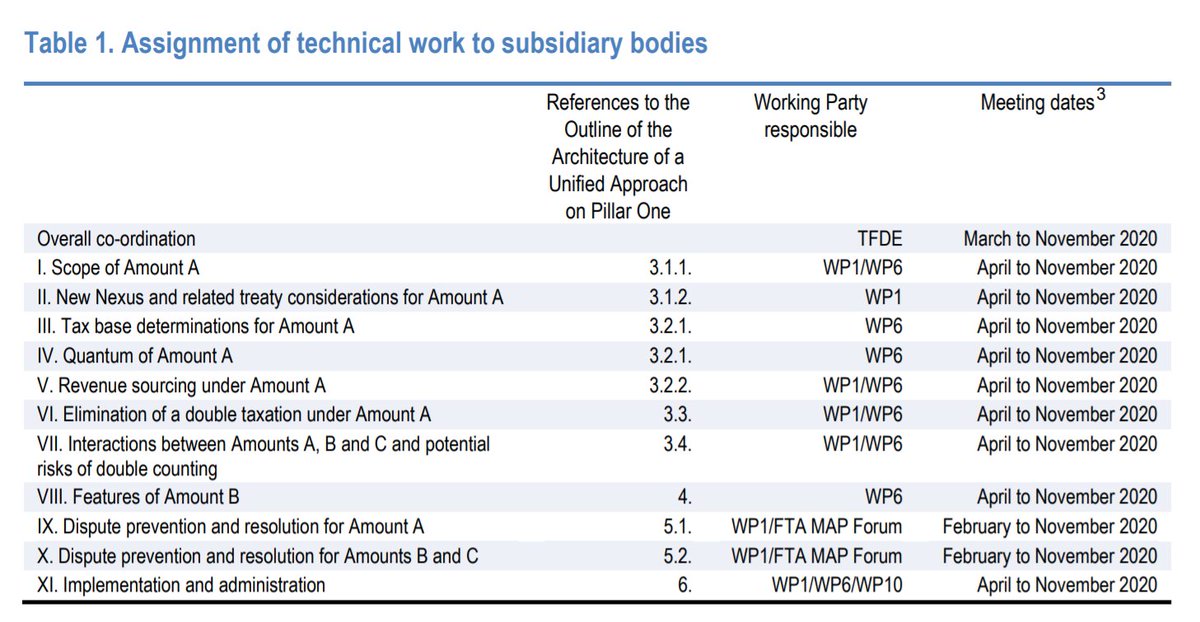

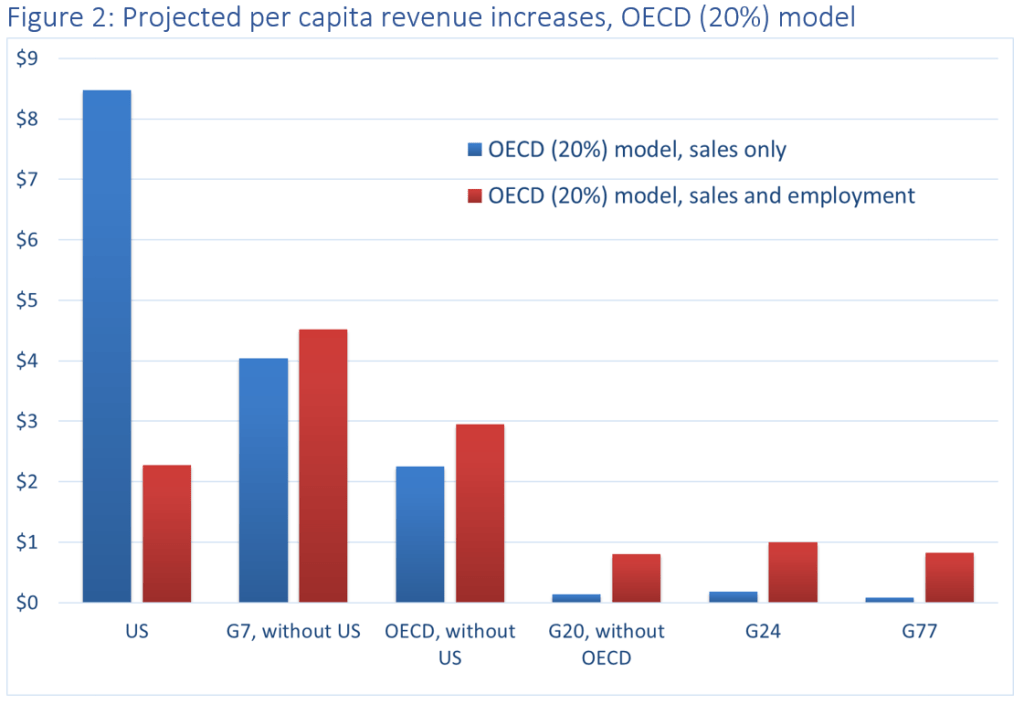

The Financial Secrecy Index grades each country’s financial and legal system against 100 datapoints, which includes compliance with various international standards, such as the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) anti-money laundering recommendations, the Common Reporting Standard and the OECD’s Global Forum standard on access to banking information. However, many existing international standards are widely recognised as being far too weak to effectively safeguard against financial secrecy. As a result, complying with international standards is often not enough to ensure effective financial transparency in practice. The is one of the primary reasons why the OECD has been working recently on proposals to reform the century-old international tax system in place today.

Under current international tax rules, multinational corporations have been able to dodge an estimated $500 billion in tax every year and offshore jurisdictions have accrued huge concentrations of untaxed private wealth. So we often set a higher bar that reflects what truly effective safeguarding against financial secrecy looks like in practice.

Our higher standards have, over the years, helped drive better international standards. We have, since our founding, advocated a number of positions – such as automatic information exchange, country-by-country reporting, and beneficial ownership transparency – which were all called unrealistic and utopian when we first proposed them. Nonetheless, all of these have become emerging international standards in the past few years. Moreover, many countries and corporations are now voluntarily complying with our more robust transparency standards that have not become international standards yet, such as online public access to registries of beneficial ownership and local filing of country by country reports whenever the country cannot obtain it via automatic exchange of information.

Claim 3: Misquoting what the Financial Secrecy Index scores the country on

The Financial Secrecy Index evaluates countries against 20 indicators, each consisting of several sub-indicators, totaling over a hundred datapoints against which each country is scored. This data is made public on the Financial Secrecy Index website and is available to download in excel files. This data is also sent to each ranked jurisdiction ahead of the launch of the index to provide jurisdictions the opportunity to identify any inaccuracies in our research in advance.

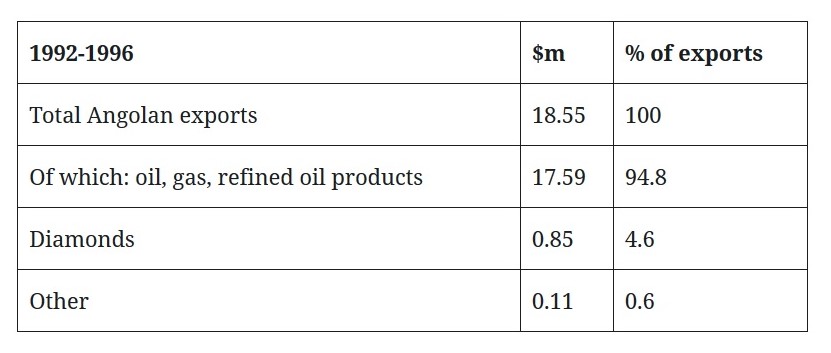

Nonetheless, some secrecy jurisdiction do not engage with this data at all and falsely claim that the index has evaluated them on something completely different. In some cases, secrecy jurisdictions misquote our press releases. More often, secrecy jurisdictions quote the historical summaries that we provide on some countries’ financial sectors alongside our evaluation and ranking of those countries’ financial and legal system. These historical summaries are independent pieces which are not factored into countries’ ranking – they’re purely additional information we provide on the history and of the secrecy jurisdiction. Perplexingly, some secrecy jurisdictions ignore the index’s latest evaluation of their financial and legal systems and instead lambast our summary of their history for being “outdated”.

For example, Cayman Finance claims that both the 2018 and 2020 edition of the Financial Secrecy Index “cite a report by the U.S. Congress’ Joint Committee on Taxation to support an allegation that U.S. corporate “foreign earnings and profits” are shifted out of other countries and into Cayman. The report was published in 2010, making the information within it eight years old when TJN included it within the 2018 FSI and ten years old.” Neither edition of the index used this report to evaluate Cayman’s ranking. The report was mentioned in the historical summary we provided in 2018 on the jurisdiction, and since history doesn’t change, the report was mentioned in the historical summary in 2020.

A similar claim is made by Luxembourg in a Delano article on the Financial Secrecy Index 2020:

Luxembourg’s finance ministry said in a statement to Delano on 19 February: “…The research methodology, for its part, on which it is based seems to be flawed, as it fails to reflect the major progress that has been achieved over the last 5 years in the field of transparency in Luxembourg.”

Indeed, the TJN report cited Jean-Claude Juncker, Luxembourg’s prime minister until 2013, 13 times, but only mentioned Xavier Bettel, PM for the past 6 years, twice.

All of these references to prime ministers were made in our historical summary of Luxembourg. These references have nothing to do with Luxembourg’s ranking on the index. Not surprisingly, Luxembourg’s response to the index did not mention any of the data on which the country was actually evaluated and ranked.

One last claim made by the Cayman government, and on the face of it more specific, is this: “The Cayman Islands does not permit shell companies, bearer shares or anonymously numbered bank accounts that conceal ownership.” But this is again, a misdirection. The index does not claim that Cayman permits bearer shares or anonymous numbered bank accounts: see points 172, 157 and 158 on our interactive database (click on Cayman). Our secrecy scores are made up of 20 indicators, so achieving low secrecy in one doesn’t make the whole jurisdiction secrecy-free. And while there is no precise definition of a ‘shell company’, this is typically taken to relate to anonymous ownership and the Index shows that Cayman has much to improve in respect of legal ownership registration for companies.

Miscellaneous claims

Cayman Finance: “The TJN’s assessment criteria are geared toward countries with direct taxation systems. Our public revenue is collected upon transactions, principally on goods, but the TJN’s methodology doesn’t account for this. For example, one of its Key Financial Secrecy Indicators (KFSI) isn’t applied to jurisdictions with indirect taxation, and so TJN arbitrarily ascribes a full secrecy score to Cayman”

The index assesses more than 130 jurisdictions and is definitely not ‘geared’ specifically towards countries with direct taxation systems. However, a lack of direct taxation is relevant for the index, mostly because it all but guarantees lower transparency. Countries that don’t have income taxes have little interest in information to keep track of taxpayers.

Like United Arab Emirates, Bahamas, and other jurisdictions we assess, Cayman does not have a direct taxation system which means Cayman does not collect information on taxpayers like other countries do. For instance, Cayman doesn’t issue tax identification numbers (TINs) which is what most countries use to identify a specific taxpayer or company. This affects Cayman’s ability to fight against corruption and money laundering.

The absence of direct income tax is also reflected in the key indicator (KFSI9) that measures the publication of cross-border unilateral tax rulings. Since Cayman does not have a direct income tax, it does not issue unilateral tax rulings, which can be abused as a form of financial secrecy (and the LuxLeaks scandal revealed how extremely harmful these rulings can be).. Cayman claims that since it does not issue unilateral tax rulings, it should not be scored as fully secretive on this indicator. However, Cayman not issuing unilateral tax rulings does not mean that Cayman has opted for transparency, but rather that it is offering a more simple form of secrecy: the outright refusal to collect any tax information.

What is more, with the OECD’s Common Reporting Standard (CRS) for automatic exchange of information (See Annex A) Cayman has taken the “voluntary secrecy” option. That means that while Cayman does send information to other countries about many non-residents, it declines to receive information from abroad on its own residents. This gives a strong secrecy signal to individuals who pay a token investment (and fees) to become a Cayman-resident “Person of Independent Means”. This often referred to as a “Golden Visa”, which gives individuals a fake residency in a country which they can use to open bank accounts in the country. When information is collected on the accounts of golden-visa holders by more transparent countries, the information is sent to the individual’s fake resident country instead of their true country of residency, where they really should be paying taxes. For golden-visa holders “resident” in Cayman, the jurisdiction under voluntary secrecy, declines to receive the information sent by more transparent countries.

Another key indicator which reflects the absence of direct income tax is KFSI 14 on “tax court secrecy.” Cayman argues it should not have received ‘not applicable’ (equal to 100% secrecy score in this case) only because it has no direct income tax and therefore does not have these types of tax court proceedings. Naturally, no one needs to go to a tax court to ask for a reduction of taxes owed, if they don’t pay tax anyway but this is definitely not an indication for being transparent. As we explained above, a lack of direct taxation guarantees lower financial transparency, and this is exactly what our index attempts to measure.

The key point, as discussed under ‘Claim 1’ above, is that jurisdictions have a responsibility for the impact of their secrecy on the tax abuse and other forms of corruption that they facilitate in other countries. For Cayman to claim that it does not need a certain measure because of its own tax system is irrelevant, if the effect of that system is to promote abuse elsewhere. Cayman remains responsible for the secrecy it sells.

Despite the hostility directed by representatives of secrecy jurisdictions towards the Financial Secrecy Index 2020, they have been unable to muster any factually-based criticisms of the index. Instead, their responses have mostly fallen under the three types of claims debunked above. Perhaps this in itself is most revealing of all.

The Financial Secrecy Index 2020 has, as of the time of writing this, enjoyed media coverage in outlets with a combined audience of more than 2 billion people. The claims put out in response by secrecy jurisdictions have reached far fewer people and likely convinced even fewer (the responses to the promoted tweets of Cayman Finance are a joyous read, for example). Nonetheless, as public pressure continues to grown on governments to clamp down on financial secrecy, some secrecy jurisdictions will become even more desperate in their attempts to misdirect scrutiny and spread misinformation. Let’s make it clear that we’re on to their act.

Featured image: “General Election – Lies & Truth – Keep the Faith!” by Diego Sideburns is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0