Nick Shaxson ■ Why tax havens will be at the heart of the next financial crisis

Update: this has now been cross-posted at Naked Captalism

This post examines another excellent in-depth investigation by Reuters into global financial stability issues, and the role of tax havens in this giant game of pain and plunder. The investigation uncovers, among other things, a whole lot of offshore shenanigans, complementing what we (and relatively few others) have been saying for some years now, and it goes right to the heart of what capitalism is — or at least what it has become.

Before reading this, though, see the box “What is a tax haven?” There’s a lot of misunderstanding out there.

What is a tax haven?

The term ‘tax haven’ is a bit of a misnomer: they aren’t just about tax. We will mostly use the term ‘offshore’ here instead of ‘tax haven’ – what we are talking about is the same basic phenomenon: jurisdictions offering escape routes to financial players elsewhere, helping them avoid taxes or disclosure or financial regulation or whatever other ‘burdens’ of society they don’t like.

In financial stability terms the world of offshore — a world that includes places like Ireland, Luxembourg, Cayman and the City of London (see box) – has been where financial services players have been able to escape regulatory barriers at home, taking the cream from risky activities while shifting the risks onto taxpayers via bailouts and other nasties. Offshore was very significantly at the root of the global financial crisis that erupted in 2008 — and on all evidence it will be at or near the epicentre of the next one too. We have written about this many times, and we have fingered London as being especially dangerous for global financial stability. And this comes in the context of the UK just having announced that they will be rowing back on money laundering checks and so on, in the name of ‘cutting red tape.’ (Read it and weep.) As was reported in the Financial Times not so long ago:

“Carolyn Maloney, a Democratic representative from New York, said there was a “disturbing pattern in the last few years of London literally becoming the centre of financial trading disasters””

Whatever one might think of Congresswoman Maloney, that statement is spot on.

This article looks at two Reuters stories in particular:

- How Wall Street captured Washington’s effort to rein in banks; and

- U.S. banks moved billions of dollars in trades beyond Washington’s reach.

The first story notes:

“[The] FASB, the private group that sets accounting standards for public companies, came under political pressure to tighten rules blamed for exacerbating the financial crisis. Critics said FASB had made it too easy for banks to stash mountains of securitized loans in off-balance-sheet vehicles based in the Cayman Islands, hiding their exposure to risks that eventually swamped them and the global economy.

Here, too, banks pushed back hard. And here, too, their protests reached sympathetic ears. Ultimately, FASB’s rules barely dented the size of banks’ off-book holdings”

. . . as the Reuters graphic here suggests. The banks, Reuters reports, hold nearly $3.3 trillion of securitized loans in off-balance-sheet entities. And that’s just Cayman and six U.S. banks.

“It isn’t just the banks. As hedge funds and private equity funds have ramped up high-risk lending in recent years, their use of off-balance-sheet vehicles has ballooned.”

There are two guilty parties here, geographically speaking: first, the United States, which shouldn’t allow this to happen; and second, “offshore” (which some think of as a single seamlessly interconnected place) where, as a general rule, the big players are allowed to do whatever they damn well like. As a former top Cayman official once put it:

“The responsibility of the Cayman government was managed by avoiding the concept of prudential regulation.”

Once again, ‘offshore’ jurisdictions and players get the cream from all the trading churn, while the ordinary taxpayer ultimately foots the bill. As Gary Gensler, former chairman of the Commodity Futures Trading Commission in the U.S. put it in the case of the AIG disaster, which was ultimately about risky trading activity in London:

AIG had been hit by its financial products unit in London while Citigroup had been harmed by special purpose investment vehicles set up in the UK capital. “So often it comes right back here, crashing to our shores … if the American taxpayer bails out JPMorgan, they’d be bailing out that London entity as well,” he told the House financial services committee.

Back to Reuters. The story trawls through a lot of colourful detail, including the work of an activist JP Morgan Vice President known as “Loophole Leslie” Seidman, as well as a number of regulatory changes after the Dodd-Frank financial reform bill which were “all in the direction of watering it down,” according to Marcus Stanley of Americans for Financial Reform. This Reuters investigation is a reminder of how much important stuff has been going on behind the scenes. They are relying on the fact that nearly everyone is tired of this stuff now.

Then Reuters moves on to this:

Which, again, is offshore: our terrain.

This article begins by looking at the apparent sudden vanishing of hundreds of billions of dollars of trades by some of the largest U.S. banks — including Goldman Sachs, JP Morgan Chase, Citigroup, Bank of America, and Morgan Stanley — to get around U.S. derivatives rules. (Tax havens and wild-west derivatives trades seem to go together like Bonnie and Clyde.) Reuters summarises:

“The trades hadn’t really disappeared. Instead, the major banks had tweaked a few key words in swaps contracts and shifted some other trades to affiliates in London, where regulations are far more lenient. Those affiliates remain largely outside the jurisdiction of U.S. regulators, thanks to a loophole in swaps rules that banks successfully won from the Commodity Futures Trading Commission in 2013. . .The products affected by that loophole include some of the most widely traded financial derivatives in the world.”

We wrote at length about this too: Reuters summarises it like this:

“The lobbying blitz helped win a ruling from the CFTC that left U.S. banks’ overseas operations largely outside the jurisdiction of U.S. regulators.

. . .

Once the banks got that loophole, then a lot of that predatory behavior migrated overseas to wherever there was less regulation.”

. . .

While many swaps trades are now booked abroad, some people in the markets believe the risk remains firmly on U.S. shores. They say the big American banks are still on the hook for swaps they’re parking offshore with subsidiaries.”

(We’d only dispute the word “believe” in that second-last sentence: it should be “know.”)

In case anyone were crazy enough to think that this stuff has stopped, the indefatigable Americans for Financial Reform a few days ago came out with news of this latest godawful exemption.

And now, as an aside, here’s a little snippet that Reuters unearthed, which we hadn’t seen before, about a big pre-GFC crisis:

“Gensler often told people how, at the Treasury, he was stuck with the task of briefing then-Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin about Long-Term Capital Management in 1998. The Connecticut hedge fund collapsed under $1.2 trillion in swaps booked to a post office box in the Cayman Islands.”

Cayman again. LTCM was a biggy – causing global market carnage at the time. However, the only book today’s blogger has read about it – Roger Lowenstein’s otherwise excellent When Genius Failed — does not mention Cayman once in the footnotes. You will hardly find it mentioned here or in other detailed analyses. This wasn’t on anyone’s radar screens at all. And far too few people are paying attention to the financial stability threats that lie offshore, hidden and unknown until crisis hits.

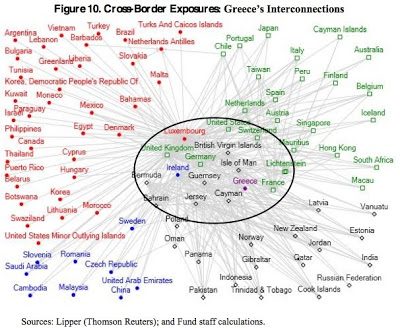

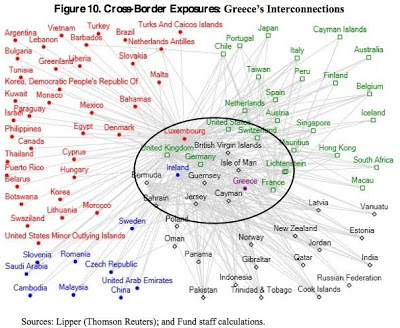

Now this isn’t to say that the next crisis won’t be triggered and significantly caused by an economic collapse in China, or an asteroid strike, or something. But the last big crisis showed — if you look carefully — how tightly connected all this stuff is, and how offshore is so often at the heart of it. This IMF graph from 2010 is one of the only bits of research that really points the finger offshore. (Even then, though, they pussyfoot around using such emotive words such as ‘tax haven’ or ‘offshore.’) But just look at that rogues gallery in the cross hairs: BVI, UK, Luxembourg, Ireland, Bermuda, Cayman, Jersey, Isle of Man, Switzerland, Liechtenstein. And of course the United States.

As mentioned, this stuff goes to the heart of what capitalism has become. All this regulatory arbitrage, like tax cheating and so much other stuff that is going on, is a form of what academics call rent-seeking, and we prefer to call ‘wealth extraction.’ In this case, it’s ultimately about extracting wealth by gambling with other people’s money: taking risks and getting others to pay when the balloon goes up.

The more risks build up, out of sight and offshore, the more likely they are ultimately to create mayhem. Hence the headline of this post.

The world’s leaders and international financial institutions need to wake up to what offshore is, and where it is. The place to start looking is London.

Related articles

The Financial Secrecy Index, a cherished tool for policy research across the globe

New Tax Justice Network podcast website launched!

Como impostos podem promover reparação: the Tax Justice Network Portuguese podcast #54

Convenção na ONU pode conter $480 bi de abusos fiscais #52: the Tax Justice Network Portuguese podcast

As armadilhas das criptomoedas #50: the Tax Justice Network Portuguese podcast

The finance curse and the ‘Panama’ Papers

Monopolies and market power: the Tax Justice Network podcast, the Taxcast

Tax Justice Network Arabic podcast #65: كيف إستحوذ الصندوق السيادي السعودي على مجموعة مستشفيات كليوباترا

Remunicipalización: el poder municipal: January 2023 Spanish language tax justice podcast, Justicia ImPositiva

If Bitcoin becomes a safe haven that Is both a deflationary currency and significant growth asset I would expect smart money to move rapidly out of these offshore accounts and into the most liquid asset today….

Personally, it would seem this could happen well within a few hours….

It’s interesting to see these countries changing though. Those that I always assumed were tax havens have really changed over the past few years. It appears the pressure put on them by other governments is indeed changing things.

Andorra for example used to be notorious for hidden money but now it’s been removed from a lot of these lists according to https://andorraguides.com/tax/haven/ .

Increasingly countries are signing on and taking part in CRS. It seems the future is bright for tax justice.