Rachel Etter-Phoya ■ Do it like a tax haven: deny 24,000 children an education to send 2 to school

Our latest research published last week in the journal PLOS Global Public Health reveals the world has decided the educational rights of 2 Dutch children are more important than those of 24,000 Nigerian children.

It’s bewildering.

Thankfully, something is being done about it.

Rich countries retreating from global solidarity

We are seeing some of the world’s largest providers of overseas development assistance pulling back from their commitment to global solidarity, just as the majority of the world’s nations, led by Africa, is rallying behind the UN framework convention on tax to change the way the international tax system works, so there’ll be less reliance on aid and more on fairly raised taxes.

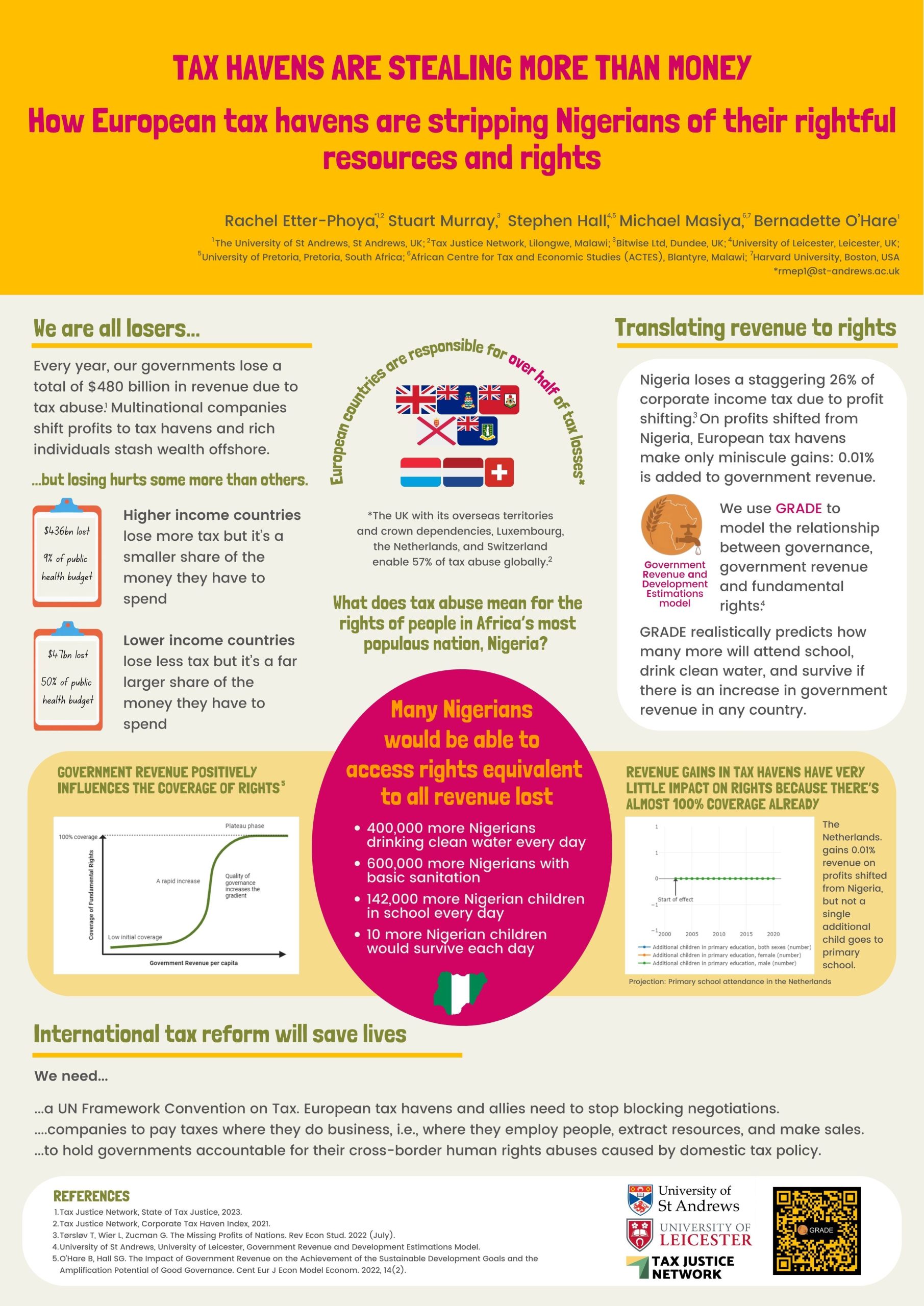

This matters deeply when the world collectively loses an estimated $492 billion through multinational corporate tax abuse and society’s wealthiest people evading tax. The richest countries lose the most in absolute terms, but the poorest countries lose the most relative to their budgets since they’re more reliant on those revenues. Even though the richest countries lose in the billions, they are also some of the biggest global enablers of tax abuse, including Switzerland, Ireland, the Netherlands, and the UK, with its overseas territories and crown dependencies.

You may be asking yourself why this is happening when most countries, even the richest, desperately need more money for health, education, better transport connections, and more housing. You name it, the list is long.

So what do European tax havens stand to gain in terms of their ability to look after their own populations by providing access to fundamental economic and social rights through luring corporate profits made in other countries? And what’s the impact on rights in countries that are losing out on tax revenue on these shifted profits? A group of us—including child rights advocates, tax experts, and economists from the University of St Andrews, University of Leicester and the African Centre for Tax and Economic Studies—wanted to find out.

There can be ‘no rights without revenue’

Tax havens are an anathema to human rights. When tax havens enable companies and people to dodge paying their fair share of tax where they do business or where they live, governments have fewer resources to spend on making sure we have a healthy and safe environment, our children can go to school, and our mothers do not die in childbirth.

Over 70 years ago, the world agreed on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, guaranteeing the right to education and health. Our national governments are primarily responsible for meeting those obligations. Still, every country also has extraterritorial obligations to mitigate the adverse impacts of its companies and domestic policies in other countries.

For this reason, multiple UN human rights bodies, including the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, have called out countries such as the Netherlands and Ireland for the deleterious impacts of their cross-border tax policy. The Committee asked the Netherlands to

Conduct independent and participatory impact assessments of its tax and financial policies to ensure that they do not contribute to tax abuse by national companies operating outside the State party that lead to a negative impact on the availability of resources for the realisation of children’s rights in the countries in which they are operating.

United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child

Our loss, their gain?

Collecting fair taxes from companies is critical. Corporate income tax often makes up one-fifth of tax revenue in Africa, Asia and the Pacific, but almost 40% of multinational profits are shifted each year.

The problem is that estimating the money countries lose to companies that shift profits to tax havens, and the gains tax havens are making is notoriously tricky when so much tax abuse hides under a veil of secrecy. For our study, we used the only data available on profits shifted from source countries to destination tax havens, originally published by Thomas Tørsløv, Ludvig Wier and Gabriel Zucman. You can take a look around the world of Missing Profits for yourself.

We focused on Nigeria as an interesting case study and as one of the only African nations with this data. Multinationals shifted an estimated 26% of their profits out of Nigeria 2019, so the country lost over 3% of government revenue. Nearly one-quarter was lost to European tax havens. The largest tax loss, over $200 million, was to the Netherlands. Yet the tax revenue generated in European tax havens as a result of profit shifting from Nigeria was almost negligible: 0.01% of government revenue.

2:24,000

Large numbers are meaningless to most of us, so we used the Government Revenue and Development Estimations (GRADE) model to translate how many children live (or die) as a result of profit shifting, how many more (or less) people can access clean drinking water, and how many more (or less) children can finish primary and secondary school.

The GRADE model works by realistically assuming governments allocate additional revenue in the same way they have over recent decades. It takes into account the quality of governance, and incorporating the impact of additional revenue on governance it accepts that revenue increases take time to show impact.

The impact of profit shifting varies dramatically between countries. If the Nigerian government had additional revenue equivalent to tax revenue lost from profit shifting:

- 500,000 more Nigerians would have access to clean water

- 800,000 more Nigerians would have access to basic sanitation

- 150,000 children would be able to go to school each day

- 11 more children would survive each day (totalling 4,063 children each year)

European countries tax corporate profits shifted to their jurisdictions at relatively low rates. Coverage of essential social and economic rights in European countries is almost universal. Therefore, their populations do not gain much in terms of essential rights from shifted profits from Nigeria.

Let’s take the Netherlands. If they stopped enabling profit shifting from Nigeria, an additional 24,000 Nigerian children would be able to go to school each day, and this would impact the educational rights of 2 Dutch children.

How do we fix this?

Thankfully, this situation is far from inevitable.

We need national and international action to close the loopholes for profit shifting—double tax treaties need rewriting, tax ‘incentives’ granted to multinationals need carefully evaluating, and governments must require multinational companies wanting to do business in a jurisdiction to publicly disclose their profits, taxes, and assets on a country-by-country basis.

Tightening the screws won’t be enough though, because the global tax system needs reprogramming. This is now possible with ongoing negotiations for the UN Framework Convention on International Tax Cooperation. The convention seeks to end tax havens, level the playing field so multinational companies pay their fair share of tax, and create the first truly inclusive global body to manage cross-border tax. This, instead of the current arrangement where the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) decides the international tax rules—an organisation made up almost exclusively of the richest and most powerful nations, often former colonial powers, who are largely responsible for enabling global tax abuse.

A finalised UN global tax convention could be voted on by the 193 UN member states in 2027 and then, it’ll be open for signature and ratification.

Tackling threats to progress

It’s not all smooth sailing, though. While Nigeria has led the charge with the African Group for these structural reforms to end profit shifting, notorious tax haven countries, including the Netherlands, have hindered progress. Nonetheless, the majority of the world’s nations voted in favour of the convention’s terms of reference last year.

Now, however, governments need to find ways to increase extra-budgetary support for negotiations because the UN’s liquidity crisis has led to a hiring freeze for the already-agreed-upon secretariat, which is to provide the technical and operational backstop for negotiations.

Last month, the US delegation, under the new US presidency of Donald Trump, walked out of the UN tax meetings and also ended its support for the rich-country-led tax rule-making at the OECD. Now that the US will not be disrupting negotiations from within, and given its aggressive stance towards countries trying to assert their tax rights, countries that have until now been hesitant about or tried to block enhancing the UN’s role in this area, including the UK, Australia, Japan and European Union members, should seize the opportunity for global solidarity.

Countries must now decide if they will support the African Group and Global South bloc to collectively exercise their right to tax major multinationals or give in to the US administration’s coercive tactics, as we analysed last month. The lives and well-being of many children around the world depend on it.

Related articles

Malta: the EU’s secret tax sieve

The Bitter Taste of Tax Dodging: Starbucks’ ‘Swiss Swindle’

Disservicing the South: ICC report on Article 12AA and its various flaws

11 February 2026

What Kwame Nkrumah knew about profit shifting

The last chance

2 February 2026

After Nairobi and ahead of New York: Updates to our UN Tax Convention resources and our database of positions

The tax justice stories that defined 2025

Let’s make Elon Musk the world’s richest man this Christmas!

2025: The year tax justice became part of the world’s problem-solving infrastructure