Telita Snyckers, Liz Nelson, Sergio Chaparro-Hernandez, Layne Hofman ■ Why the world needs UN leadership on global tax policy

Countries have a historic choice to make this year’s end at the UN: stay the course on global tax with the OECD or support moving leadership on global tax to the UN.

This briefing explains why countries should support the move to the UN. Nearly US$5 trillion of future public money is on the line.

Table of content:

The cost of tax abuse

Who leads global tax policy today?

Key issues with the OECD’s tax leadership

Why UN leadership?

Recommendations

A single nation, or privileged group of nations should not be dictating the terms upon which our global societies function. And yet they do.

The historic vote at the UN General Assembly in November 2022 for growing the UN’s role in international tax marks an important watershed moment for solidifying the transition towards more inclusive decision making and broader space for progressive policies. Crucially, this process can generate major gains for societies all around the world, by re-establishing the scope for fairer taxation for all.

If countries continue blindly on the course followed for the past 10 years on international tax rules, the State of Tax Justice 2023 estimates that countries will lose US$4.8 trillion over the next 10 years. By comparison, countries around the world collectively spent $4.66 trillion on public health in a single year. The 2007-2009 Great Recession is estimated to have led to a loss of US$2 trillion in global economic growth. Tax losses over the next 10 years would have twice the impact of the Great Recession on the global economy.

To avert these astronomic losses, countries must democratise how global tax rules are determined by supporting a move to UN tax leadership.

In an increasingly connected world, global standards, coordination, and cooperation are of paramount importance. As economic and social interactions transcend national borders, it becomes essential to establish common norms and practices that ensure consistency, fairness, and efficiency.

Global standards serve to promote transparency, accountability, and a level playing field for businesses and individuals alike. Moreover, coordination and cooperation among nations foster mutual understanding and enable joint efforts in addressing shared challenges such as climate change, cybersecurity, and public health.

By working together, countries can pool resources, share best practices, and achieve outcomes that go beyond what any one country could on its own. In a world where interconnectedness is the norm, global standards, coordination, and cooperation serve as vital pillars for promoting stability, sustainable development, and the wellbeing of people across the globe.

There are global governance structures – under auspices of the UN – for peace and security, human rights, sustainable development, global health, environmental protection, international law, justice, and trade. And yet, despite tax keeping countries ticking and our economies intertwined, there is no global governance structure for tax.

This autumn, governments around the world will have a realistic, once-in-a-century opportunity to take back control of their tax systems and turn tax back into a tool for equality.

The cost of tax abuse

Every second, our governments lose the equivalent of a nurse’s yearly salary to a tax haven.

Global tax abuse steals billions in public money and rob billions of people of a better future. But it doesn’t have to be this way.

At the Tax Justice Network we believe tax is a social superpower in pursuit of equality. Tax funds our public services, strengthens our economies and makes our democracies healthier – all of which create the opportunities that make a good life possible for everyone.

But for decades, under pressure from mega-corporations and the superrich, our governments have increasingly programmed our tax systems to prioritise the desires of the wealthiest over the needs of everybody else. A handful of corporations and billionaires have been allowed to capture untold wealth and, in the process, have made our economies too weak to provide adequate livelihoods, and big, sometimes dirty, money was allowed to squeeze people out of having a say in their own democracies.

This injustice needs to be undone, and tax justice campaigners are already working with governments on this.

Taxes constitute some 70 per cent of revenues for lower income countries, which are also significantly more reliant on corporate taxes than higher income countries. These countries face real challenges in broadening their tax base and can ill afford the depletion of tax revenues they are legitimately entitled to.

We cannot afford the half a trillion dollars of tax revenue lost each year to cross-border tax abuse. We cannot afford the undermining of progressive taxes on income and wealth that follows, and the inequalities that result. We cannot afford the loopholes in national law and international rules that are created and exploited by an entire industry of tax professionals and lobbyists for vested interests. We cannot afford the antisocial tax behaviours that see the top 1 per cent of households responsible for more than a third of unpaid tax in a country like the United States, while multinational companies’ unpaid taxes in lower income countries equate to half of these countries’ public health budgets.

Tax havens are growing unabated despite measures introduced to curb the tax abuse they enable. The percentage of corporate profits held in tax havens has steadily risen for decades and is now more than triple what it was in the mid-80s.

Global governance of tax in the 21st century requires a genuinely inclusive and representative forum at the UN to replace the rich country members’ club, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (the OECD). A breakthrough in the 2022 UN General Assembly saw a resolution unanimously adopted, mandating the Secretary-General to prepare a report on the options and modalities for negotiating such a framework, and beginning intergovernmental discussion.

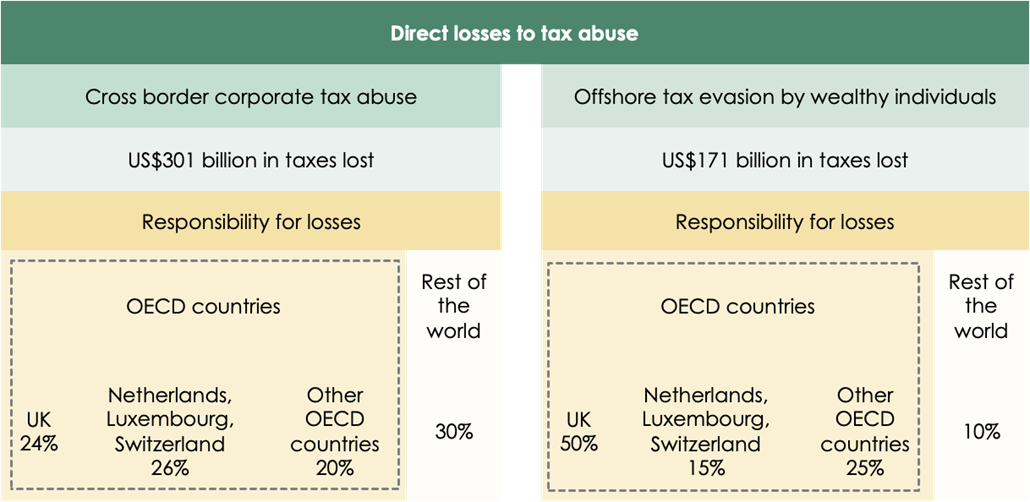

US$1.15 trillion worth of corporate profit is shifted by multinational firms into corporate tax havens a year, for no reason other than to artificially reduce the amount of tax payable. As a result, our governments are losing US$311 billion in corporate taxes that should have been paid, and an additional US$169 billion in taxes lost through wealth hidden in tax havens – every year. This brings annual total global tax revenue loss to US$480 billion.

Other areas of government spend are equally under-resourced: in the past 40 years most international meetings and policy documents on education finance have focused on international aid or concessional loans. But these make up only 3 per cent of the financing of education, and official development assistance only accounts for 18 per cent in low-income countries and 2 per cent of education spending in lower middle income countries. The international benchmark calls on governments to allocate between 15-20 per cent of national budgets to education – a standard few lower income countries can meet. As a result, in 2019, 63 million children of primary school age were no longer attending school.

The broad scale of tax abuse is not an academic discourse or a theoretical construct – it has a direct and tangible impact on our lives and on our communities. It results in service delivery failures at every level. If governments cracked down on tax abuse, 28.9 million more people would have access to basic sanitation, 14.3 million people would have clean drinking water, and almost 11.4 million more children would be able to attend school – every year. The increased government spending that would be available would, over a decade, avert the deaths of 443,254 children, allowing them to survive their childhood.

Lower income countries are hit harder by this tax revenue loss. The average low income country has a tax to GDP ratio of just 16 per cent, falling way short of middle income countries that are nearer to 30 per cent or high income countries that often exceed 40 per cent.

Taxes are the most significant and sustainable source of revenue in low and lower middle income countries, constituting 70 per cent of their total revenues. Of this, corporate tax contributes much more (about 13 per cent) to low income countries’ tax revenues than it does in high income countries (about 7 per cent). This makes securing the corporate tax base in these countries critical. It also makes any restrictions on their ability to collect whatever taxes are legally due even more dire. Tax policy should be helping these countries to grow their corporate base so it can contribute even more than the current 70 per cent of government revenues, instead of hindering them, as it currently does.

While higher income countries lose more tax, their tax losses represent a smaller share of their revenues (9.7 per cent of collective public health budgets). Lower income countries by comparison collectively lose the equivalent of nearly half (48 per cent) of their public health budgets.

Who leads global tax policy today?

There is no representative, multilateral, coordinated shepherding of global tax policy today.

In the absence of a structured global policy development space, the OECD has informally taken on the mantle over the past sixty years, even though it was never constituted to do so. Its efforts may be visible, but it is not representative, it does not have a legitimate mandate to develop international tax policy, and its policies have failed to secure systemic change.

Global tax governance needs to deliver a transformation for justice and fairness. Such a transformation will not be delivered by the OECD, an institution that is neither representative nor has a legitimate mandate to develop international tax policy. Moreover, the OECD’s seemingly narrow definition of sustainable development, limited to a model of economic competitiveness with significant spill over impacts on non-member states, fails to set policies that can coherently deliver sustainable development for all our people or our planet. The policy regime the OECD has tried, and failed, to deliver since 2013 is characterised by a lack of inclusivity and by reliance on voluntary country compliance, with no consequences for non-compliance. OECD member countries are responsible for the bulk of tax losses as a result of abusive practices.

Key issues with the OECD’s tax leadership

Key issue 1: Lack of representation and mandate

Today, the UN Tax Committee has observer status in certain OECD tax-related bodies, such as the Committee on Fiscal Affairs, allowing it to participate in discussions, to contribute to the development of OECD tax standards, and to provide input. It’s an intrinsically problematic arrangement, where the agency best placed to lead tax policy development, is instead relegated to one that is allowed to merely make an input.

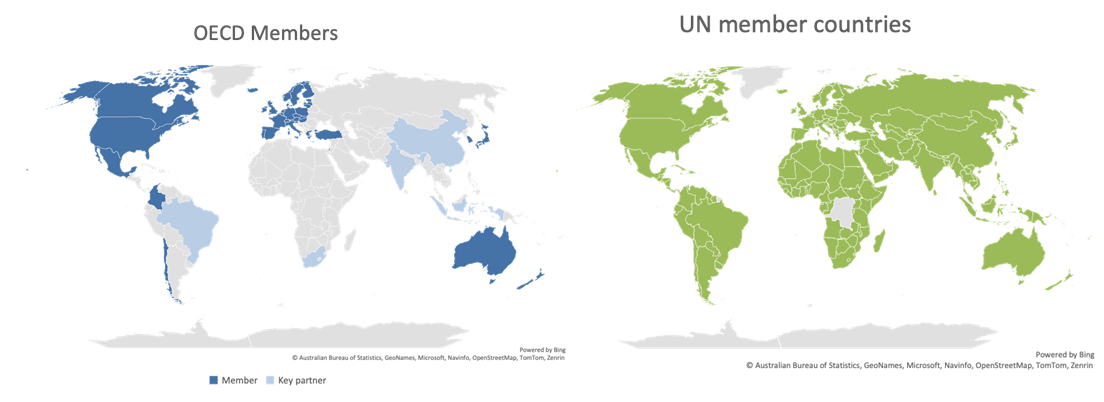

The OECD positions itself as an international organisation that works on international standard-setting, sitting “at the heart of international cooperation.” It in fact only represents a small percentage of countries and is demonstrably not representative of low or middle income countries.

- The OECD’s own articles require it to prioritise member states. The OECD is simply not capable of playing a globally inclusive role because it was never constituted to do so.

- The OECD has 38 member countries – compared to the UN’s 196.

- Its members consist of high income countries with developed economies. None of their member countries are classified as low or middle income economies.

- The organisation’s decision-making processes do not involve or represent the interests of low and middle income countries and emerging economies.

Example – G24 side lined in favour of US-France proposal

- In 2013 the OECD established its Base Erosion and Profit Shifting initiative.

- It failed to deliver any meaningful reforms.

- Lower income countries were then invited to participate in an “inclusive” framework process – but which required countries to accept the first BEPS without any say.

- In 2019 BEPS 2 started with the “inclusive” framework giving a workplan to evaluate a multilateral G24 proposal for a comprehensive shift to unitary taxation, along with two other proposals from other countries including the US and UK.

- The secretariat never delivered the promised evaluation of the various proposals that were tabled.

- Instead it came back with a “unified” proposal which simply reflects the bilateral proposal that had been made by France (where the OECD is based) and the US (the OECD’s biggest member.) This bilateral proposal for unitary taxation would only apply to those with a turnover above €750 million.

- The bilateral proposal was accepted.

- The multilateral G24 proposal was ignored in its entirety.

- The dramatically watered-down proposal was supposed to have come into effect in 2020. It still has not.

- Their policy recommendations and guidelines tend to favour the interests of its more affluent member countries. As a result, the influence of major economies, particularly the United States, within the OECD has the potential to side line the concerns and needs of smaller or less influential member states. As a result, smaller, lower income countries are excluded from or marginalised during negotiations.

Example – Double taxation agreements favouring OECD members

Double taxation agreements based on the OECD’s model treaty template (of which there are some 3,500), result in tax revenues flowing to the OECD countries where the multinationals are headquartered – and not where the economic activities are being performed, or where the resources are being extracted, and where tax therefore should more reasonably be paid. The model treaty embeds privileges for the states where companies have their residence – which are typically OECD countries, at the expense of other jurisdictions

- The OECD’s decision-making processes lack transparency and are not sufficiently open to public scrutiny. Important policy discussions and decisions within the organisation are often conducted behind closed doors, accompanied by heavy, opaque lobbying – both of which limit the accountability and democratic legitimacy of the OECD’s actions.

By contrast, the UN is the global institution designed to host the negotiation of complex issues with many competing interests and has a track record of important successes. Central to its approach are transparency about the positions taken by individual countries; democratic principles of decision-making, including voting; and a globally inclusive membership. These elements can shift outcomes significantly, as governments become accountable to one another and to their own people, for their support or objection to specific proposals.

The UN has not yet taken up stewardship of global tax policy development. This is not because it is not capable of doing so, nor because it is not the obvious place for it. It is a matter of priority. The UN is well positioned to be the steward for global tax policy development. It is capable of doing so and indeed is the obvious place for it. Yet insufficient funding and vested interests maintain the current porous approach. While the UN is contributing to the debate, it is not yet driving it. Its tax committee is under-resourced and under-staffed and does not (yet) have the same profile in tax policy development as the OECD does.

Key issue 2: Voluntary adoption of unenforceable recommendations

The recommendations and guidelines issued by the OECD are not legally binding or enforceable. There are no penalties or sanctions imposed by the OECD itself for non-compliance. The lack of enforcement mechanisms undermines the impact and relevance of the organisation’s initiatives.

Having enforceable standards with meaningful accountability is important. Once a convention or agreement is adopted, member states are legally bound by its provisions, and are required to develop national legislation, policies, and measures that align with the convention’s objectives.

Failure to comply with UN decisions have exactly that kind of meaningful accountability through tangible consequences like diplomatic isolation, economic sanctions, travel restrictions and legal proceedings before international courts. Of course there are countries that fail to meet their obligations and commitments under UN agreements or protocols. But unlike the current situation with tax policy, there is a level of deeper transparency supporting broader societal goals and environmental sustainability. We know that the US has not fully implemented various UN agreements, including, for example, the Paris Agreement. We know that North Korea has reneged on a number of its commitments particularly in respect of nuclear weapons. Sudan and Myanmar have failed to meet their human rights obligations; and Russia faces ongoing criticism for contravening international law.

These country-specific examples serve to strengthen the argument: they show that the UN monitoring mechanisms work, and that the reporting mechanisms have the ability to flag countries who fail to meet their obligations. It represents a level of transparency and accountability almost entirely lacking in the global tax policy space.

Because the UN’s processes and engagements are largely transparent, it is easier to hold it – and its members – accountable for the decisions they make, and for their adherence to those decisions. Its reporting mechanisms and monitoring bodies allow the broader public to understand the extent to which member countries are meeting their obligations; and to hold member states accountable for their commitments and obligations.

Key issue 3: Focus on economic competitiveness at all costs

The OECD’s emphasis on competitiveness revolves around traditional economic indicators, such as GDP growth and productivity, with policies that prioritise the needs of multinational corporations over locally based competitors, in a way that has nothing to do with genuine business productivity or true innovation. Instead, capital and production should gravitate to where they are most genuinely productive. Indeed, countries like Japan, with its 29 per cent tax rate, and Denmark, with its 55 per cent tax rate, prove that one does not need artificial tax “competition” to see real economic growth.

Tax competition only results in wealth being redistributed upwards, in regressive tax systems that ask more from low and middle income families than from the wealthiest, and where the poor may in fact pay more tax than the wealthiest. It results in falling corporate income tax contributions despite rising corporate profits. As with all tax abuse it helps nobody, anywhere, produce a better product or service. It lets multinationals out-compete smaller, locally based competitors, in a way that has nothing to do with genuine business productivity or true innovation.

The narrow focus on “competitiveness” aside, the OECD’s recommendations and policies are generalised and apply a “one-size-fits-all” approach, which fails to account for the unique circumstances, cultural differences, and developmental stages of individual countries. Instead of developing sensible global tax policies, current rules instead allow for some bizarre practices with no commercial substance:

Example – Bizarre practices of regressive tax policies

- American multinationals reported 43 per cent of their foreign earnings in five small tax haven countries: Bermuda, Ireland, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Switzerland. Yet these countries account for only 4 percent of their foreign workforces and just 7 per cent of their foreign investments.

- The profits that American multinationals claimed to earn in Bermuda equates to 18 times of that country’s entire annual economic output.

- Apple’s structure resulted in it paying an effective tax rate of 0.005 per cent on its European profits; and 14.8 per cent on its global profits.

- Nike operates 1,142 retail stores throughout the world – not one of them is in Bermuda. Nevertheless, it runs its books through Bermuda in the process securing it an effective tax rate of 1.4 per cent.

- Goldman Sachs has 511 subsidiaries in Cayman Islands, despite not operating a single office in that country – the group officially holds US$31.2 billion offshore.

Key issue 4: Structurally biased implementation

After 10 years, the OECD’s restrained implementation efforts have not led to significant improvements in the scope of global tax abuse. This is not because the solutions are necessarily wrong but because the principles have been compromised and diluted to the point of inefficacy, or reneged on altogether.

There are multiple examples that highlight how measures have been compromised or reneged on, in the process rendering them ineffective. The lack of traction is attributable to everything from exclusionary processes, to being susceptible to the vested interests of the wealthiest:

- A common reporting standard for the automatic exchange of information between tax administrations is an enormously powerful tool to overcome bank secrecy and the associated undeclared offshore accounts. Although more than 110 jurisdictions have signed up to the OECD’s common reporting standard, the exchange of information between tax administrations is characterised by a number of systemic failures:

- All the major financial centres are included – except the USA.

- Its impact has been significantly weakened through a provision that the information exchanged may only be used for tax purposes (and not, for instance, as part of money laundering investigations).

- Most of the lower-income countries remain excluded due to spurious requirements for reciprocity, which can be extremely difficult for less developed countries to comply with.

- Only 9 of the 54 African countries and 2 of the 46 least developed countries have adopted the measure.

- Unitary taxation to counter base erosion and profit shifting. The OECD reform process in 2019 conceded that the arm’s length principle – put in place by the League of Nations a century ago – is not fit for purpose and is at odds with the G20’s single tax goal (in place since 2013) of better aligning taxable profits with the location of real economic activity. Instead, the current arm’s length principle makes profit shifting relatively straightforward. The better alternative is to assess taxable profit globally at the unit of the multinational, rather than at an entity level within the group, and then to apportion those profits between countries of operation. Despite committing to the principle of unitary taxation in principle, the scheduled delivery date for even a watered-down version – 2020 – has long passed, and ambitions around this principle appear to have all but collapsed.

- Country by country reportingis necessary to reveal the misalignment between where real economic activity takes place, and where profits are declared for tax purposes. Key failures include the following:

- The OECD standard currently applies only to the largest 10−15 per cent of multinationals (those with a turnover above three quarters of a billion euro).

- The OECD standard does not require that the data be reconciled with the published, global consolidated accounts of multinationals.

- A number of countries do not use the agreed reporting template.

- Most lower income countries never get access to the data – because multinational company headquarters are rarely based there.

- The OECD committed to publishing the data from 2019. However, the OECD has only published the information twice – and then in an aggregated and anonymised manner.

- Many countries refuse to give permission for any of their data to be made public, which renders it powerless to secure accountability for either companies or the jurisdictions that facilitate their profit shifting and as a result more than US$1 trillion of corporate profit continues to be shifted to tax havens.

- The OECD is yet to deliver a response to its 2020 review, when investors and civil society were nearly unanimous in calling for the adoption of the much more robust global reporting initiative standard.

- As with the automatic exchange of information, only 9 of the 54 African countries and 2 of the 46 least developed countries have been able to join the process; and even these do not enjoy full access as other countries pick and choose who to provide information to.

- To date not a single low income country has received any information pursuant to country by country reporting.

Example – UK U-turn impedes global tax transparency

The UK blocked the OECD from publishing its aggregated country by country data in a timely manner in 2022, reneging on its 2016 commitment to do so. The UK is estimated to have missed out on at least £2.5 billion in corporate tax a year as a result.

- A minimum global tax rate to counter base erosion and profit shifting. A minimum global tax rate has started gaining some traction, but in eg the EU it is being introduced at 15 per cent (compared to the 21-25 per cent that had been discussed), and only for groups with revenues of more than €750 million a year. The USA has noted its unwillingness to adopt a minimum global rate in principle. Also, as Switzerland has shown, it is being used to even further entrench tax havenry, rather than eradicate it.

While these changes have only partially been introduced, and then at a snail’s pace, they do show that norm shifts are possible – including developing genuinely inclusive alternatives in other spaces such as the UN.

Early proposed drafts for a UN tax convention, and the UN High Level Panel on International Financial Accountability, Transparency and Integrity, have all recommended implementing undiluted, fully robust versions of the above solutions as well as other long called for policy solutions for addressing global tax abuse and financial secrecy.

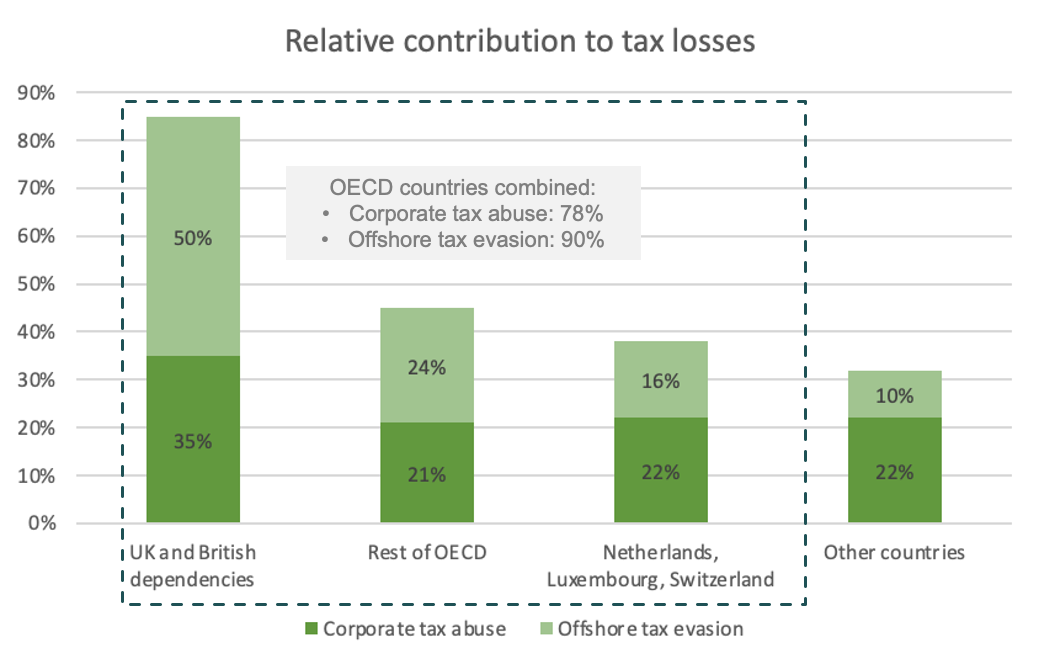

Key issue 5: OECD members are the key contributors to tax abuses

The OECD’s stewardship is even more problematic considering that OECD countries are responsible for the majority of global tax losses to offshore wealth.

The OECD is not able to rein in abusive practices by its members. As we show in our State of Tax Justice reports for 2020, 2021 and 2022 and now most recently for 2023, OECD member countries and their dependent territories are consistently responsible for some 70 per cent of global cross border corporate profit shifting and tax abuse, and some 90 per cent of all taxes lost to offshore evasion by high wealth individuals in tax havens.

Just policies do not deliver just outcomes when they are delivered through institutions that are inherently biased. As in the title of Audre Lorde’s famous essay, “The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house”.

Why UN leadership?

The UN is the right institution to shepherd global tax policy development: it is the single most representative global body; its specialist technical bodies and legal frameworks were designed precisely to coordinate and harmonise global practices; and it secures accountability through enforceable binding agreements and reporting mechanisms.

Representation

The UN is the single most representative global body – only two countries in the world are not members (the Vatican City, and Palestine.)

Its extensive membership gives it a global perspective of global issues, including the sustainable development goals, and how trade and financial systems impact their achievement. In a world where our financial systems are characterised by the race to the bottom – seeing who can tax multinationals the least – and where success is simply measured by the bottom line for shareholders, this more balanced view is more critical than ever. The UN’s Sustainable development Goal 17, for instance, specifically emphasises the revitalisation of global partnerships for sustainable development, including promoting a universal, rules-based, open, and non-discriminatory multilateral trading system.

Importantly, because it is also home to the many smaller or lower income countries, it also considers the spill over effect of policies on countries that are often marginalised during policy development.

Most recently, the European Parliament recognised the need to finally introduce a globally inclusive process for determining tax standards in its resolution calling on EU members states to back negotiations for a UN tax convention.

Specialist agencies

The UN has a rich history of establishing and overseeing some of the most impactful specialist agencies, that deal with highly complex, technical issues. A number of these focus on trade and commerce. This is important in this context: taxation is (often) just the flip side of trade. Tax, trade and debt are intimately intertwined, to the point where the one cannot exist without the other.

Examples of the UN’s specialist bodies and agencies include:

- The United Nations Convention on Climate Change, which established an international environmental treaty to combat “dangerous human interference with the climate system” – work that was only possible at the UN level.

- The UN’s DESA secretariat for sustainable development goals.

- The UN Committee of Experts on International Cooperation in Tax Matters, which provides guidance and promotes cooperation among countries. It serves as a platform for countries to exchange views, share experiences, and develop international tax standards. The committee has contributed to the development of important documents like the UN Model Double Taxation Convention and the Transfer Pricing Manual.

- The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade – the precursor to today’s World Trade Organisation, which is the primary international organisation responsible for governing global trade. It provides a platform for negotiations, sets trade rules, and resolves trade disputes among member countries.

- UNCTAD, which focuses on trade and development issues, particularly with respect to developing countries. It provides research, policy analysis, and technical assistance to help countries integrate into the global economy, address trade-related challenges, and promote sustainable development-oriented trade policies.

- The International Trade Centre, a joint agency of the WTO and UNCTAD, supports particularly small and medium-sized enterprises in developing countries to participate in international trade. It offers market intelligence, trade promotion services, capacity-building programs, and trade-related technical assistance.

- The UN Development Programme, which also engages in trade-related activities to support inclusive and sustainable economic growth. It provides policy advice, capacity-building, and project support to help countries integrate trade into their development strategies and foster trade-related development outcomes.

- UNIDO, the United Nations Industrial Development Organisation promotes inclusive and sustainable industrialisation. It works with member states to enhance their productive capacities, to improve competitiveness, and to integrate into global value chains.

- The UN’s various regional economic commissions, which play a regional role in promoting economic cooperation, including trade, among its member states They provide a platform for dialogue, policy analysis, and technical assistance on trade-related issues like trade facilitation, standards, and regulations.

- The International Organisation for Standardisation which develops and promotes global standards for products, services, and systems, enhancing compatibility and reducing technical barriers to trade.

Technical legal frameworks and conventions

In addition to its specialist agencies, the UN has promulgated a variety of conventions which focus on a wide range of global challenges, including human rights, environmental protection, disarmament, health, labour rights and gender equality. The conventions provide a platform for dialogue, exchange of information, cooperation, technical assistance and capacity building between countries. They are important, not just from a legal perspective, but also in the way they foster a sense of collective responsibility and solidarity, and for their ability to act as catalysts for more progressive and inclusive approaches to issues.

Notable policy successes include the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the Sustainable Development Goals, the Paris Agreement under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, and the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. By addressing these challenges collectively, conventions foster a global response that transcends national boundaries and promotes international cooperation.

There are multiple examples that highlight the value of multilateral intergovernmental dialogue. These have resulted in several progressive moves towards intergovernmental cooperation and inclusive negotiations for tax justice, progress towards the sustainable development goals and the realisation of rights, as proposed by the African nations, G77 and others. Initiatives involving strong multilateral, inclusive engagement focusing on reform in international tax include:

- Coordination and collaboration between the Africa Group and G77 at the UN, resulting in this most recent very historic vote at the UN;

- The High Level Panel of the African Union and the UN’s Economic Commission for Africa on illicit financial flows out of Africa;

- The UN Secretary General’s initiative on financing for development during the pandemic; and

- The UN’s High Level Panel on International Financial Accountability, Transparency and Integrity for Achieving the 2030 Agenda.

The UN’s trade agreements in particular have fundamentally and indisputably improved global trade. These include multilateral trade negotiations which were critical in reducing trade barriers and promoting the liberalisation of international trade, like:

- The Uruguay Round (1986-1994), which led to the creation of the World Trade Organisation.

- The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade.

- The Trade Facilitation Agreement, which provides a common framework for countries to implement efficient and transparent trade facilitation measures, reducing costs and delays.

- Regional trade agreements that contribute to harmonising trade rules and promoting regional economic integration.

- The UN’s technical expertise underpins its focus on technical assistance and capacity development to all of its member countries.

Accountability

Having enforceable standards is important. Once a convention or agreement is adopted, member states are legally bound by its provisions, and are required to develop national legislation, policies, and measures that align with the convention’s objectives.

Transparency

Because the UN’s processes and engagements are largely transparent, it is easier to hold it – and its members – accountable for the decisions they make, and for their adherence to those decisions. Its reporting mechanisms and monitoring bodies allow the broader public to understand the extent to which member countries are meeting their obligations, and to hold member states accountable for their commitments and obligations.

Recommendations

The current way of doing things has failed us.

In the late autumn, countries have an opportunity to vote on formally starting negotiations on a UN tax convention that would establish a new UN leadership role on international tax. This is a once-in-a-century, realistic opportunity to develop a genuinely inclusive and just global tax convention with globally inclusive standards. We finally have a real chance to secure agreement on and implement solutions that are effective in curbing tax abuse by multinationals and high net worth individuals, and other illicit financial flows. The Tax Justice Network’s advocacy efforts centre around the following recommendations:

- Build on the existing work of the UN Tax Committee and the Africa Group’s Resolution to begin intergovernmental cooperation on tax matters at the UN.

- Establish a new, fully resourced intergovernmental tax bodywithin the United Nations.

- Establish a Centre for Monitoring Taxing Rights at the UN to raise national accountability for illicit financial flows and tax abuse suffered by others.

- Develop a genuinely inclusive and just United Nations global tax convention with globally inclusive standards, that also considers spill over impacts on lower income countries, and that secures just taxing rights for all.

- Secure agreement on and implement solutions that are effective in curbing global tax abuse by multinationals and high net worth individuals, and other illicit financial flows. These could include, for instance, solutions that the Tax Justice Network has long advocated for:

• Automatic exchange of information on financial accounts between countries, removing barriers of reciprocity that currently impede lower income countries’ access to this crucial public good.

• Beneficial ownership transparency of the ‘flesh and blood’ owners of assets, trusts, foundations and other forms of wealth. This should include public beneficial owner registers (for the wealthiest), building towards a single interconnected global system.

• Comprehensive and publicly available country by country reporting for all multinational companies.

• A minimum effective corporate tax rate, based on the global profits of each multinational group and allocated according to a formulary apportionment model that ensures taxes are paid in the jurisdictions of actual economic activity.

• A global asset register, linked to country level asset registers, to track ownership by high wealth individuals.

A UN tax convention offers the best chance in a century – in fact the only real chance in a century – to establish globally inclusive rules and standards to end cross-border tax abuse.

Related articles

The elephant in the room of business & human rights

UN submission: Tax justice and the financing of children’s right to education

14 July 2025

How the UN Model Tax Treaty shapes the UN Tax Convention behind the scenes

The 2025 update of the UN Model Tax Convention

9 July 2025

One-page policy briefs: ABC policy reforms and human rights in the UN tax convention

UN Submission: A Roadmap for Eradicating Poverty Beyond Growth

A human rights economy: what it is and why we need it

Do it like a tax haven: deny 24,000 children an education to send 2 to school

Urgent call to action: UN Member States must step up with financial contributions to advance the UN Framework Convention on International Tax Cooperation

The Most Socially Just Tax

Our present complicated system for taxation is unfair and has many faults. The biggest problem is to arrange it on a socially just basis. Many companies employ their workers in a variety of ways and pay them differently. Since these companies are registered in various countries within a number of categories, the determination the general criterion for a just tax system based on earnings becomes impossible, particularly when it depends on a fair measure of the quality and amount of human work-activity. So why try to do this when there is a better means available for taxation, which is really a true and socially just method?

Adam Smith’s (“Wealth of Nations”, REF. 1) says that our natural resource of the land is one of the 3 factors of production (the other 2 being human labour and durable capital goods). The usefulness of a particular site is expressed by its purchase price and in the amounts that tenants willingly pay as rent, for its access rights. Land is often considered as being a form of capital wealth, since it is traded similarly to other durable capital goods items. However, it is not actually man-made, so rightly it does not fall within this category. Indeed, the land was originally a gift of nature (if not of God), for which all the people in the region should have equal rights for sharing in its opportunities for residence, accessibility and use.

However, over many years, as communities became established and grew, the land has been traded as if it was an item of durable goods and today it is often treated as a form of capital investment. It is apparent that for a particular site, its current site-value greatly depends on location, size and to the population density in its region, as well as the amount of natural resources that it can steadily provide. Such bounty is manifest in the exploitation of rivers, minerals, plants and animals of specific use or beauty. These are available only after local developments have made possible easy access to the particular locality. Consequently, much of the land value is created by man within his society, by his need and ability to reach it and take from it materials, growing plants and live creatures, as well as the opportunities it provides for working space near to people. These advantages should ethically and logically be justly returned to the community, as if for its general use within the government, as explained by Martin Adams (in “LAND” REF 2.).

However, due to our existing laws, the land is owned and formally registered and its value is traded, even though it can’t be moved to another place, like other kinds of capital goods. This right of ownership gives the landlord two big advantages over the rest of the community. He/she can determine how it may be used, or if it is to be held out of use for speculative reasons, until the city grows and the site becomes more valuable. Secondly the land owner enjoys the rent from a tenant or its equivalent if he uses the land himself. Speculation in land values and its rental earnings are encouraged by the law, in treating a site of land as personal or private property as if it were an item of capital goods, even though this is not true, see Prof. Mason Gaffney and Fred Harrison: “The Corruption of Economics”, REF. 3.

Regarding taxation and local community spending, the municipal taxes we pay are partly used for improving the infrastructure. This means that the land becomes more useful and valuable without the landlord doing anything—he/she will always benefit from our present tax regime from which the land value grows when the status of unused municipal land is upgraded and it becomes more fitting for community development. When the news of an upgrade is leaked, after landlords and banks corruptly pay for this valuable information, speculation in land values is rife.

There are many advantages if the land values were taxed instead of the many different kinds of production-based activities such as earnings, purchases, capital gains, home and foreign company investments, etc, (with all their regulations, complications and loop-holes). The only people due to lose from this different regime of taxation are those who exploit the growing values of the land over the past years, when “mere” land ownership confers a financial benefit without the owner doing a scrap of work. Consequently, for a truly socially just kind of tax to apply there can only be one method–Land-Value Taxation.

Consider how land becomes valuable. Pioneers and new settlers in a region begin to specialize and this slowly improves their efficiency in producing specific kinds of goods. The land central to the new colony is the most valuable, due to its easy availability and the least necessary transport of its produce. After an initial start, a graduated distribution in land values is created by the community. It is not due only to the natural land resources. As the city expands, speculators in land values will deliberately hold potentially useful sites out of use, until planning and development have permitted their more intensive use and for their values to grow. Meanwhile there is fierce competition for access to the most suitable sites for housing, agriculture, manufacturing industries, transport byways, etc. The limited availability of the most useful land means that the high rents paid by tenants make their residence more costly and the provision of goods and services more expensive.

Entrepreneurs find it difficult or impossible to compete with the big organizations who have already taken full advantage of their more central sites. The greater cost of access, or the greater expense in transportation from less costly outlaying regions, discourages these later arrivals. It also creates unemployment, causing wages to be lowered by the land monopolists, who control the big producing organizations, and whose land was previously obtained when it was relatively cheap. Consequently, this basic structure of our current macroeconomics system, works to limit opportunity and to create poverty, see above reference.

The most basic cause of our continuing poverty is the lack of properly paid work and the reason for this is the lack of opportunity of access to the land on which the work must be done. The useful land is monopolized by a landlord who either holds it out of use (for speculation in its rising value), or charges the tenant heavily for its right of access. In the case when the landlord is also the producer, he/she has a monopolistic control of the land and of the produce too, and can charge more for this access right than what an entrepreneur, who seeks greater opportunity, normally would be able to afford.

A wise and sensible government would recognize that this problem of poverty derives from lack of the opportunities to work and earn. It can be solved by the use of a tax system which encourages the proper use of land and which stops penalizing everything and everybody else. Such a tax system was proposed about 140 years ago by Henry George, a (North) American economist, but somehow most macro-economists seem never to have heard of him, in common with a whole lot of other experts. (I would guess that they even don’t want to know, which is even worse!) In “Progress and Poverty”, REF. 4, Henry George proposed a single tax on land values without other kinds of tax on earnings, sales of produce, services, capital-gains etc. This regime of land value tax (LVT) has 17 features which benefit almost everyone in the economy, except for landlords, tax collectors and banks, who/which do nothing productive and find that land dominance and its capitalistic exploitation have their own (unjust) rewards.

17 Aspects of LVT Affecting Government, Landowners, Communities and Ethics

Four Advantages for Government:

1. LVT, adds to the national income as do other taxation systems, but it should replace them. The author has shown in REF.5, that taxation of any kind is beneficial to the whole country, due to its national income providing for more work too, but that when the tax applies to land the topology and spread of its effects are about 3 times as beneficial as when the same amounts of income are taken directly from labor.

2. The cost of collecting the LVT is less than for all the production-related taxes–tax avoidance becomes impossible, because the sites are visible to all and who owns each site is public knowledge. The army of tax collectors who are opposing a similar set of lawyers, are no longer busy with tax loopholes in the law, so the number of people more productively employed will grow and the penalty on the country of having complicated taxation is less.

3. Consumers pay less for their purchases due to lower production costs (see below). They can buy more goods and enjoy a raised standard of living. This creates greater satisfaction with the management of national affairs and more prosperity.

4. The national economy stabilizes—it no longer experiences the 18-year business boom/bust cycle, due to periodic speculation in land values (see below). The withholding of unused land is eliminated see item 7, so there is less need for the complications of frequent land sales, with developers searching and buyers hunting for unused sites.

Six Aspects Affecting Landowners:

5. LVT is progressive—this tax depends on the site area as well as its position. The owners of the most potentially productive sites pay the most tax per unit of area. Urban sites provide the most usefulness and their owners will pay at greater rates, whilst big rural sites have less value and can be farmed appropriately, to meet their ability to provide useful produce. Smallholder farming closer to population centers becomes more practical, due to local markets and reduced distribution costs.

6. The landowner pays his LVT regardless of how his site is used. A large proportion of the present ground-rent from the tenants (who do use the land properly), becomes transformed into the LVT, with the result that the land has less sales-value but retains a significant “rental” value.

7. LVT stops speculation in land prices, because the withholding of land from its proper use is not worthwhile.

8. The introduction of LVT initially reduces the sales price of sites, even though their rental value can grow over a longer term. As more sites become available, the competition for them is less fierce and entrepreneurs have more of a chance to get started.

9. With LVT, landowners are unable to pass the tax on to their tenants as rent hikes, due to the reduced competition for access to the additional sites that come into use.

10. Speculators in land values will want to foreclose on their mortgages and withdraw their money for reinvestment. Therefore LVT should be introduced gradually, to allow these speculators sufficient time to transfer their money to company-based shares etc., and simultaneously to meet the increased demand for produce (see below, items 12 and 13).

Three Aspects Regarding Communities:

11. With LVT, there is an incentive to use land for production, transport, or residence, rather than it being vacant and held unused.

12. With LVT, greater working opportunities exist due to cheaper land and a greater number of available sites. Consumer goods become cheaper too, because entrepreneurs have less difficulty in starting-up their businesses, and because they pay less ground-rent–consequently demand grows, whilst unemployment and poverty decrease.

13. Investment money is withdrawn from land and placed in durable capital goods. This means more advances in technology and cheaper goods too because the effectiveness of labour has been raised.

Four Aspects About Ethics:

14. The collection of taxes from productive effort and commerce is socially unjust. LVT replaces this national extortion by gathering the surplus rental income, which comes without any exertion from the landowner or by the banks–LVT is a natural system of national income-gathering.

15. Previous bribery and corruption for gaining privileged information about land, cease. Before, this was due to the leaking of news of municipal plans for housing and industrial development, causing shockwaves in local land prices (and municipal workers’ and lawyers’ bank accounts!)

16. The improved use of the more central land of cities reduces the environmental damage due to unused sites being dumping-grounds, and the smaller amount of fossil-fuel use (with its air-pollution), when traveling between home and workplace.

17. Because the LVT eliminates the advantage that landlords currently hold over our society, LVT provides a greater equality of opportunity to earn a living. Entrepreneurs can operate in a natural way– to provide more jobs because their production costs are reduced. Then untaxed earnings will correspond more closely to the value that the labour puts into the product or service.

Consequently, after LVT has been properly and fully introduced as a single tax, it will increase national prosperity, eliminate poverty and improve business ethics.

Best wishes,

David Harold Chester

References:

1. Adam Smith, 1776: “The Wealth of Nations”, UK

2. Martin Adams, 2015: “LAND– A New Paradigm for a Thriving World”, North Atlantic Books, California, USA

3. Mason Gaffney and Fred Harrison, 2005: “The Corruption of Economics”, Shepheard-Walwyn, London, UK

4. Henry George: “Progress and Poverty” 1897, reprinted 1978 by the Schalkenbach Foundation, New York, USA

5. David Harold Chester, 2015: “Consequential Macroeconomics—Rationalizing About How Our Social System Works”, Lambert Academic Publishing, Saarbüchen, Germany