Nick Shaxson ■ What does Brexit mean for tax havens and the City of London?

By Nicholas Shaxson

It is Mansion House time again. Every year Britain’s Chancellor (finance minister) makes a speech at Mansion House, a spiritual home of Britain’s financial sector and the official residence of the Lord Mayor of London, where he (the Chancellor is always a ‘he’) declares his love and support for the country’s oversized financial sector, promises to tread lightly on tax and regulation, and urges it on to greater glories.

The latest speech just given by the current Chancellor, Rishi Sunak, was no exception, praising ‘ground breaking’ new financial services deals with the tax havens of Singapore and Switerland, defending “the global norms of open markets,” and “sharpening our competitive advantage in financial services.”

The words ‘competitive advantage,’ or ‘competitiveness’ when applied to a financial sector, are clear warning signals for those of us who look closely at these things. To be precise, they are signals of a dangerous ideology, one that prioritises the interests of mobile financial capital over those of broad populations and democracies. And since Britain formally exited from the European Union last December 31st, these signals have been coming thick and fast.

In January, for instance, Greenpeace UK launched a petition containing this:

“Bee-killing neonicotinoids have been banned across Europe since 2013, but the UK government has just approved these deadly chemicals.”

A few hours later, the Financial Times published this:

“UK workers’ rights at risk in plans to rip up EU labour market rules.”

Soon afterwards, Big Four accounting firms appeared to be delighted about plans to opt out of certain EU transparency rules about abusive tax arrangements. There has been talk of loosening stock market listing regulations. We hear that the UK is relaxing regulations on ‘dark pools’ – profitable trading platforms for investors, away from scrutiny, and potentially cutting back on various other finance-related rules and regulations. The government has announced plans for “freeports” (or “sleazeports,” hat tip) which have a record around the world for hothousing criminality and abuse and failing to boost even local economic growth. The UK is stepping outside an EU ban on exports of potentially toxic plastic waste to lower-income countries. Fears are rising that the UK may position itself as a “data haven” of lax standards, to attract predatory data-hungry businesses. The Penrose Report, an official review of UK competition policy released in mid-February, looks like another deregulatory push in a “power to the people” packaging. Forces are now pushing hard for a new super-regulator to ensure that UK finance regulators are more “supportive” of the City of London.

Inside the ruling Conservative Party there has been a clamour for a wider “bonfire” of regulations and tax cuts, even as they continue to pursue broad austerity for the majority of the population. As one wag put it on twitter:

“We have a rather crap car in this race, so we can make it ‘competitive’ by removing the roll cage, fire extinguisher, mirrors, brake lights etc.”

It’s a strategy to win a supposed race, that carries, shall we say, risks.

Power struggle

The deregulators don’t have it all their own way. Many remember the carnage of the last global financial crisis, spurred in large measure by “competitive” deregulation of this kind, much of it happening in London under a Labour government. (There are voices among the ruling Conservatives urging caution too.)

Even Chancellor Sunak seems divided, up to a point. He has joined the arsonists in advocating a “Big Bang 2.0” for the City of London – a reference to Margaret Thatcher’s explosive deregulation of finance in the late 1980s, which helped lay the conditions for the global financial crisis and the rise of finance into a near-invincible position of power in the UK. On the other hand, the same Chancellor Sunak recently hiked headline corporate tax rates significantly and admitted – shockingly to many Conservatives – that:

“Over the last few years haven’t seen that step change in the level of capital investment that businesses are doing as a result of those corporation tax reductions.”

Many bosses of big businesses and even finance companies are saying they don’t want to slide further along this slope either. More striking still, even the tax directors of major multinationals are saying that tax cuts hardly influence investment decisions, and that they largely support higher taxes on multinationals as part of wanting to “do the right thing.” This line of thinking is the opposite of the race-to-the-bottom “competitive” mentality, and there are extremely welcome signs coming from the United States now, where the Biden Administration has made some profound philosophical shifts in this area, as we’ll see below.

But in the UK, the deregulators have the upper hand

Yet in terms of public policy, the overall direction seems to be downwards, into a post-Brexit race to the bottom, as we have warned before.

Britain is walking further along the tax haven road – a strategy of degrading taxes, rules and enforcement in the hope of luring money from the oceans of mobile capital that roams the world hunting for kid-glove treatment, secrecy and handouts. Brexit, according to this model, ‘frees Britain to compete’ without burdensome EU regulations to hold it back. This would, as the Tax Justice Network’s John Christensen said in a speech to the European Parliament in 2019, “give the fox full access to the henhouse.”

The EU is taking a dim view of this broad direction, with almost no current prospects for the City of London to be granted “equivalence” status which would recognise the UK’s regulatory regime to be good enough to allow UK-based financial firms to sell services seamlessly across the EU. In the absence of equivalence, significant financial activity has already migrated to Europe.

This article will explore four big questions. Where does this “competitive” model come from? Was Brexit “caused” by tax haven actors and the City of London financial centre? Who will win, and who will lose, specifically, if this bonfire of financial regulations goes ahead? And how could Britain channel this momentous rupture in better, healthier directions?

Along the way, this article will expose the great ‘national competitiveness’ hoax and show why a strategy of pursuing this rootless global capital does not just hurt other nations: it harms Britain too.

Once we understand this we can see how Britain can act unilaterally in its own interest, doing exactly the opposite of what a supposedly “competitive” strategy would entail, and without needing to be part of a collaborative international project like the EU. A clear alternative path would re-invigorate British democracy and boost prosperity at the same time. This path lies in actively seeking to shrink the financial sector back to its useful core, and to implement “smart capital controls” in particular ways to exclude harmful financial activity from the UK.

How did we get here? Empire 2.0

Was the City of London financial centre and the “offshore interest” in Britain behind Brexit?

Not exactly. Many if not most people and institutions in the City of London actively opposed Brexit. Most of Britain’s large banks, law firms and insurance businesses had long grown used to the rules of the EU Single Market, which granted them “passporting rights” allowing them to establish branches in and do business across the zone with minimal cross-border kerfuffle, while being regulated and supervised in their home country. British tax havens like Jersey and Guernsey were mostly not cheerleading the Brexiteers: although they were previously locked out of the Single Market for financial services, suggesting that Brexit may not be such a rupture for them – it will be hard, because without Britain to lobby for them in Brussels, they are now more vulnerable to things like EU blacklists.

No, the British rupture with Europe has many fathers: Europhobic media barons; genuine anger at distant and élite EU technocrats (and at a mostly pro-EU British élite establishment that helped deliver the global financial crisis and other marvels); billionaires buying influence or mis-direct public anger about inequality and deprivation towards “wokeness” and other cultural memes; or dark-money funding for Brexit politicians who then lied about the benefits of Brexit, and more.

But finance, and especially offshore finance, certainly played a big role. To grasp this, it is necessary first to understand how finance gained such a grip on British politics, society and even culture – and how the “offshore interest” became so powerful within the financial establishment.

The City of London, (or “The City,” the colloquial term for the UK’s financial services sector,) was the “governor of the imperial engine,” as the historians Cain & Hopkins put it in their seminal title British Imperialism: it was the big global turntable for loans and finance across the colonies and beyond. The City grew rich and powerful, and became the dominant political force in Britain, particularly since the 19th Century.

After the finance-induced Depression of the 1930s, the world began to appreciate more keenly the dangers of letting finance become too dominant, or flow freely across borders. After the Second World War governments implemented progressive economic policies: eye-wateringly high taxes on rich people; nationalisations, powerful antimonopoly stances – and stringent controls over finance, including very tight curbs on cross-border financial flows.

This financial ‘repression’ and progressive policy-making lasted for a quarter-century after the War. The City and Wall Street loathed it – but it fostered what is now called the “Golden Age of Capitalism”: economic growth was higher, and more broad-based, than in any period of world history, before or since. (For more on all this, read this or watch this.)

As prosperity spread widely, however, powerful forces were already massing against the controls.

The first happened around the time of the Suez crisis of 1956, when Britain and France lost control over the Suez canal in a humiliating defeat. Colonies saw how weak the war-shattered imperial powers now were, and a wave of decolonisation followed. Britain’s dominant élites were doubly horrified because of their double sense of entitlement: first, that Britain should “rule the waves”, and second, that a certain class of finance-focused, overseas-looking ‘gentlemen’ should rule Britain. These people began looking for a grand new post-imperial role – and they found it in a new offshore model.

A new strain of finance emerged in London in 1956, the year of the Suez crisis. Essentially, banks began doing international business in London that wasn’t denominated in the Pound Sterling currency and was thus not plugged into the British economy. This wasn’t allowed under the international “Bretton Woods” rules to curb cross-border financial speculation, but the Bank of England decided to treat the activity as if it were happening “elsewhere” (which meant, in effect, nowhere) and opted not to regulate it.

Foreign banks, especially American banks, noticed fast: operating in this libertarian “offshore” zone was far more profitable than under the tight “onshore” controls, and this so-called “Eurodollar” market grew explosively. Meanwhile, a string of British “Overseas Territories” and “Crown Dependencies,” the residue of Empire, still substantially under British control, began to carve out niches as tax havens, offering secrecy and an almost complete absence of rules. Bankers in these territories – including Bermuda, Cayman, the British Virgin Islands and Jersey – began gleefully hoovering up drugs money and the proceeds of all sorts of other nefarious activity. This “Spiderweb” of British tax havens got plugged into the London-based Eurodollar market, while other non-UK tax havens joined in, from Switzerland to Panama, creating a rather seamless offshore zone where money could flit across borders at the click of an accountant’s pen (and, later, at the click of a computer mouse.) This system for escaping the Bretton Woods controls became the silent, hard battering ram of global finance, which from the 1970s onwards began punching ever bigger holes in the leaking international controls that had underpinned the Golden Age of global prosperity and stability.

Along with this battering ram came a story, a complementary ideology: a globalised version of what gets called neoliberalism. Neoliberalism is the idea that anything that isn’t nailed down should be sold off to the private sector and thus shoveled into the price mechanism and the rigours of “the market,” which would constantly sort everything into winners and losers and thus deliver the best and most efficient possible world. A wave of think tanks and academics, often based in Chicago, began to wield clever models full of mathematics, to push the idea that universities, hospitals, train networks – even the office buildings under the feet of Her Majesty’s tax inspectors – should be sold off, to be sorted by the hyper-efficient sorting machine of the market.

But it wasn’t just people and things and public life that needed to be judged by “the market”. Under a vision first formally theorised by the US academic Charles Tiebout – who first offered his theory up as a joke – it was whole countries too, which could “compete” heroically in a Panglossian market-based global sorting machine. Each nation would offer bundles of tax rates and regulation, together with packages of infrastructure and educated and healthy workforces, for the delectation of rootless capital. Investors would flit from one jurisdiction to the next in great shoals, ripping their kids out of schools and uprooting their factories, at the drop of a tax inspector’s hat.

In this formulation, society was absent and financial capital, picking and choosing from this global smorgasbord, was firmly in the driver’s seat. Countries had no choice but to be “competitive”: low taxes, loose regulations, an absence of “red tape,” and no ‘snooping’ on the activities of clever people by clod-hopping government bureaucrats. Financial secrecy was all the rage.

The Competitiveness Agenda

British Prime Ministers, from Margaret Thatcher to Tony Blair to Boris Johnson, fell under the sway of this “Competitiveness Agenda.”

To foreign audiences, as the historian Matthew Watson put it, Blair spoke of the opportunities from globalisation and from investing in Britain, managing expectations upwards; while to domestic audiences, he managed expectations downwards, couching globalisation as more of a threat: that business interests needed to win out over workers, taxpayers, and the general public (p103).

This wasn’t just a British agenda: a raft of “Third Way” politicians around the world had similar views that rootless global capital must be pandered to. Witness US President Bill Clinton’s belief in kow-towing to finance for “competitiveness’” sake, or Germany’s Harz reforms to underpay German workers in order to promote German exports, for example. What set the British model apart from many others was the focus on finance: the most dangerous of all the sectors to play around with.

In 2005, just ahead of the global financial crisis, Blair urged that we “roll back the tide of regulation,” decried “over-zealous enforcement,” and advocated that “those doing well get a light touch approach.” He attacked financial regulators for being “hugely inhibiting of efficient business by perfectly respectable companies that have never defrauded anyone.”

The global financial crisis that erupted soon afterwards, and the public anger that followed, should have consigned this Competitiveness Agenda to the dustbin of history. After all, it merely gave substance to what every sane economist has always known, that this kind of “competitiveness” is, as the economist Jonathan Portes put it, “meaningless fluff. . . a distraction from what is really going on” (p106). We will explore this, further down.

The zombie agenda lives again

Such was the idea’s potency, however, and its deep grip on Britain’s politics and culture, not to mention its convenience to the finance-heavy ruling classes, that it survived – softened after the crisis somewhat, but still very much alive today.

Before the global financial crisis, UK financial laws referred to the “desirability” of maintaining Britain’s competitiveness in financial regulation. The word was expunged from the lexicon after the crisis, and in particular from the 2012 Financial Services Act, amid a widespread recognition that it was a ‘competitive’ race on laxity between New York and London in particular that caused so much of the damage. Yet although the c-word was mostly expunged from public discourse after the crisis brutally exposed its bankruptcy, it was merely driven below the surface, waiting, hoping, to return.

Like mushrooms that are merely the surface fruitings of giant underground fungal organisms, a host of dog-whistle phrases signified the survival of the Competitiveness Agenda: “open for business;” “global, free-trading Britain;” “freedom to compete;” “top-ranked financial centre;” “proportionate financial regulation.” and still, at times, despite everything that happened in the crisis, a “competitive” tax system or financial sector” (e.g. Section 2.44) Some talk of a “Singapore on Thames” model, with the Asian tax haven as being something to aspire to, without thinking too hard about the parallels.

The concept is now, post Brexit, rallying for a comeback. A new Financial Services Bill, now being processed, has snuck worrying clauses back in, with a proposed duty for regulators to “have regard” for the attractiveness of the UK as a place for “internationally active investment firms to be based or to carry on activities.” That is the competitiveness agenda, by stealth, right there. More openly, a new report from a Task Force for Innovation, Growth and Regulatory Reform calls repeatedly for using regulatory laxity, and shows that people are becoming bolder about using the c-word again, with sentences like: “UK regulation can be a significant driver of our international competitiveness.” (Watch a data privacy expert skewer the report, here.)

Brexit, in this view, has been a chance to let Britain stride forth in the world, unburdened by Brussels’ red tape, and to “compete” again with the greatest, putting British businesses on their toes, spurring them to ever greater feats of dynamism and innovation.

This Competitiveness Agenda dovetails with another alluring idea, again broadly supported by the general public because it sounds reasonable and most people haven’t thought too hard about it. This is the idea that Britain’s route to national prosperity is through growing the City of London financial services sector. As in, ‘More finance makes us rich: and too much tax and regulation here will make the City ‘uncompetitive’ so we’ll hurt the country. So we must swallow our envy and just let those clever rich people do their thing and generate the wealth and the jobs and take the tax revenues where we can.’

The leading proponent of this Big-City ideology is TheCityUK, a peculiar public-private lobbying force, “directed, organized, co-ordinated and encouraged by a state agency as a matter of strategic national importance,” whose speciality is to publish glowing but utterly twisted assessments of the “contribution” of the finance centre to the UK economy – reports that are often regurgitated by busy (or craven) finance journalists.

The essence of this idea – that the financial sector is Britain’s goose that lays the golden eggs, and must be treated deferentially –well, who questions it? Former Bank of England governor Mark Carney pursued it, gushing in 2017 about the prospects of a City twice its size if Brexit goes well. The link between this idea and the Competitiveness Agenda is simple: if a bigger City makes Britain more prosperous, and mobile finance can flee elsewhere if it doesn’t get what it wants, shrinking the City, then Britain has to pursue ‘competitiveness’ in financial services, to make financial services bigger, in the national self-interest.

We will soon explore why the very foundations of this vision rest on elementary fallacies and intellectual quicksand. But first, it is worth briefly side-tracking into a darker, crystallised version of this vision: a mini-ideology held by a small but powerful vested interest, with its own élite sub-culture and its own outsized impact on Brexit.

The offshore vested interest

Britain’s government, and to a degree its political system, media and even society, has come significantly under the thrall of a loose, rather libertarian alliance (or “solar system”) of influential people plugged into offshore tax havens. The players in this ‘offshore’ interest nursed a mix of reasons, personal, political and ideological, behind their support for Brexit. Some, like tax haven financier Arron Banks, funded key Brexiteer lobby groups, with money from often murky sources, with connections from people linked to the disastrous corruption-fueled mass privatisations after the collapse of the Soviet Union, including Boris Johnson’s former “Rasputin,” Dominic Cummings. This loose offshore interest group also includes Jacob Rees-Mogg, an upper-class pro-Brexit politician who has been co-owner of a major offshore investment firm; Richard Tice, leader of the Brexit Party whose family has deep offshore links, and a few others.

These people, and the often mysterious money behind them, were a significant factor behind Brexit: it is quite easy to argue, given the narrowness of the vote, that their influence flipped the vote from Remain to Leave.

If there is an ideology for these hardliners, it was perhaps first espoused by Rees-Mogg’s father William, author of a book called The Sovereign Individual, a favourite of Silicon Valley libertarian times. The book foretold ever greater difficulties financing welfare states as mobile capital increasingly escaped the grubby bonds of the democratic state. Subscribing to the fictional Littlefinger’s “Chaos is a Ladder” theory of getting rich, the book urged the talented, privileged “sovereign individual” to thrive by embracing the offshore mystic, by cheerleading chaos, and by advancing the offshore project itself.

© National Portrait Gallery, London

Many adherents of the offshore world view are, like the Rees-Moggs, associated with the ruling Conservative Party. The essential idea is that Britain, broken free from the tiresome “shackles” of Europe would be “free” to deregulate, cut taxes, facilitate financial secrecy, and generally become more of a tax haven than it already is. One could argue that theirs is the freedom of the fox in the henhouse: for the “sovereign man” to better exploit the rest.

Does this “competitive” approach work? It certainly does for them. But for the country as a whole, it is a different – and widely misunderstood – story.

Upgrade for productivity, downgrade for “competitiveness”

“Competitiveness” – as in a ‘competitive’ country, or tax system, or financial regulatory system – sounds great. But it is a fools’ (or a knaves’) errand.

A couple of examples illustrate the fallacies that lie at the heart of this Competitiveness Agenda.

First, consider the near-impossibility of prosecuting crimes and abuses by major financial actors in London. In the words of Liberal Democrat peer Baroness Kramer last February:

“One of the most damning descriptions I ever heard of UK regulators … is that when a US regulator comes to an institution, that institution is in fear; when a UK regulator comes to an institution, people go and make tea.”

Baroness Kramer

© Roger Harris

Make no mistake: this is the “competitiveness agenda.” Give mobile capital an easy ride, by weakening and removing laws and rules, then not enforcing them. Kramer’s is just one in a long line of warnings about this. If you want more detail on this laxity, perhaps look at this litany of British crime-friendly laxity, or read this 2019 research report comparing US and UK enforcement of financial crimes and misdemeanours, which concluded that “The UK is effectively outsourcing its corporate financial crime enforcement to the US.”

These British failures aren’t a weakness or aberrations of a system designed by benevolent government to deter bad actors: they reflect a deliberate strategy to entice – and consequently to encourage – abusive, and even criminal actors to operate in (or via) Britain’s financial system, often via its tax havens. Once you start looking for this Competitiveness Agenda, you’ll find it everywhere.

Tax authorities have been quietly, steadily defanged: so have financial regulators, competition authorities, and others.

On tax, recent history illustrates again why this competitive strategy does not work. Britain’s policymakers long boasted of seeking “the most competitive tax system in the G20” and slashed its headline corporate tax rate, from 30 percent for most of the 2000s, to 19 percent. On the government’s own figures, each percentage point cut in the headine rate cost an estimated £3.4 billion in lost corporate taxes, equivalent to the annual salaries of over 100,000 teachers.

Is this trade-off good? Does shifting £3.4 billion (or over £37 billion, given the 11 percentage point cut) to multinationals each year somehow make Britain more ‘competitive,’ given the losses elsewhere? With that much money, you could run 20 Oxford Universities, or send a million British children to the elite Eton College, at least if you could fit them all in. And that’s not to mention other damage from these cuts: higher inequality, greater monopolisation as highly profitable giants thrive at smaller businesses’ expense, and more.

Those are quite some costs to the UK. What are the benefits to the UK? Well, all the non-partisan evidence shows that the direct benefits of these cuts generally flow to shareholders. In addition, around 55 percent of UK quoted shares are owned by non-residents, so those tax cuts aren’t just shuffling money about inside the UK from poorer to richer sections of the population: most of the benefits leak overseas.

In terms of the indirect benefits, well, this tax-cutting is supposed to attract foreign “investment” to counteract the costs. We have explained on several occasions why these tax-cut lures just don’t work. Chancellor Rishi Sunak, as a reminder, admitted that these swinging UK corporate tax cuts didn’t attract useful investment; those tax directors we mentioned just admitted the same; and survey after survey of business leaders shows that their top priorities are good infrastructure, the rule of law, healthy and educated workforces, and access to vibrant local markets – most of which require good tax revenues. In these surveys, tax cuts and lax regulations are a low priority.

So a “competitive” tax strategy has delivered a raft of costs to the wide UK population and economy, and any benefits have flowed to a far small section of people, including accountants who do very well out of the system themselves and yet are allowed to advise the government on policies. Tom Bergin’s excellent new book Free Lunch Thinking explores the cost-benefit imbalances in great detail.

So what does it mean for a country to be “competitive”?

Policies on investment and national development can take different approaches. One is “upgrading” – for example, strong public investment to improve education or infrastructure, or strong public interest regulation to shepherd and select for businesses acting in the public interest. If Germany successfully upgrades its education, that may well make Britons better off, as richer Germans buy more UK goods. Similarly, if Britain regulates to improve its own financial stability, Germans will be less likely to be impacted by financial crises. Upgrading improves one’s own long term productivity and has nothing to do with “competitiveness” relative to other countries. Everyone wins. Indeed, in a seminal 1994 article “Competitiveness: a dangerous obsession” – the US economist Paul Krugman described competitiveness as just “a funny way to say ‘productivity’.”

A second, “competitiveness” approach, involves “downgrading”. Financial capital flows freely across borders, and countries dangle incentives or subsidies to attract it. Examples include relaxing capital requirements for banks; reducing enforcement of criminal behaviour by financial actors, creating tax loopholes for billionaires or multinational corporations, eliminating minimum wages or crushing trade unions, relaxing environmental laws, or having weak competition policies that let dominant firms exploit British consumers, workers and taxpayers more easily.

These ‘competitive’ policies are always harmful in the long run. Worse, if Britain downgrades to stay internationally “competitive,” tax havens and other jurisdictions will respond in turn, provoking a race to the bottom. UK taxpayers must continually fork out ever greater subsidies to those capital owners, just to stay in the race. Downgrading regulation selects for the worst firms, most willing to exploit. Inequality and public anger inevitably rise. So does corruption, as firms jostle and lobby to access and expand the growing train of “competitive” subsidies.

The winners in this “competitive” race are – always –large monopolising multinationals and wealthy individuals, while the losers are small businesses, local communities and the general public.

One of the most significant statements on ‘upgrading’ versus ‘downgrading’ comes from the Biden administration, which has made very clear which side of the divide it stands on, in a statement on April 7 announcing a new tax package.

And this world view seems to be reflected across many policy areas. Here’s Katherine Tai, U.S. Trade Representative:

“This inequality isn’t fair or sustainable. It didn’t happen overnight. It is the result of a long pursuit of tax, trade, labor, and other policies that encouraged a race to the bottom.”

The way forward in international tax negotiations spurred by a recent meeting of G7 leaders will be messy and full of pitfalls, but this is a profound philosophical shift. Crucially, these approaches are popular. Majorities vote heavily against the ‘downgrade for competitiveness’ version because they are fundamentally anti-democratic.

In short, this ‘competitive’ race harms the countries that engage in it, and it is unpopular too. So it is worrying that in post-Brexit, Britain, as explained above, and in the words of this excellent analysis of UK financial services by Chaminda Jayanetti, “Competitiveness is making a comeback.”

And this brings us to the finance curse.

Brexit and the Finance Curse

Britain’s public, media and political classes have long been gripped by an idea that the City of London financial centre is the goose that lays our golden eggs. Organisations like TheCityUK put out streams of reports, often repeated by journalists without serious question, apparently showing the scale of the City of London’s “contribution” to the UK economy, showering jobs, investment and tax revenues on the rest of the country.

This pervasive idea has a dangerous subtext: that if this is our Golden Goose, then we need to feed it and pamper it. That is, feed it with “competitiveness” – tax cuts, deregulation, lax antitrust policies, and all that downgrading, effectively shifting wealth from ordinary people in the UK to owners of mobile financial capital, in pursuit of “competitiveness.”

This narrative is, once again, founded on elementary economic confusions.

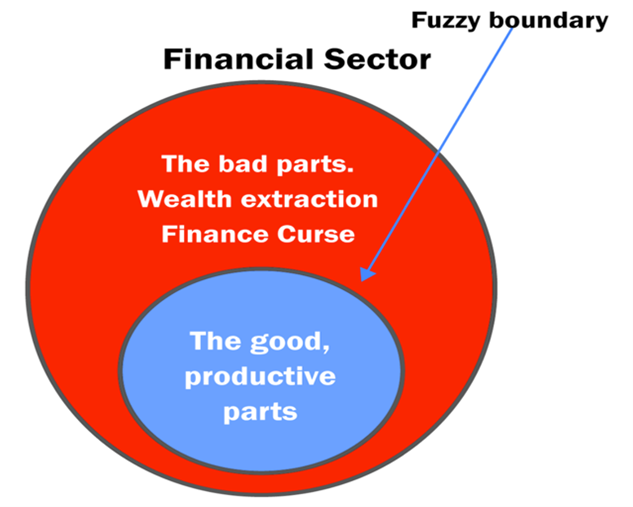

The first fallacy is those supposed “contributions” in terms of jobs and tax revenues are gross benefits, with the costs stripped out. Once you add in the costs, a very different picture emerges. This can be illustrated with two images, which we’ve used before.

The picture on the left is uncontroversial: it shows how any financial sector contains useful parts, which support the economy of the country that hosts it, and harmful predatory parts, which extract wealth from it. Clearly, there are large grey areas that are a mix of both.

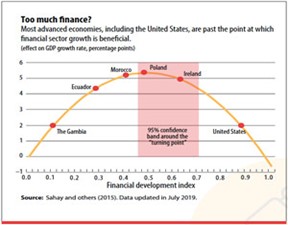

The IMF graph on the right, complementing this, reflects the findings of a growing strand of the academic literature, known as “Too Much Finance.”

Countries with underdeveloped financial sectors can usefully expand them to support their economy. But there is an optimal point, where a financial sector provides the useful services the underlying economy needs: and if it expands beyond this optimal size this reduces economic growth in the country that hosts it. Data suggests that the UK’s financial sector passed its optimal size some time in the 1980s, and just kept growing – inflicting terrible damage on the UK.

Again, we stress, excess finance does not just redistribute the pie unfairly: it shrinks the overall pie too. (There are other reasons for the apparent paradox that “too much finance makes you poorer” beyond predatory rent-seeking: see our first co-authored academic paper on this, from 2016.)

This leads to a simple proposal or slogan: that for countries past the optimal point, like the United Kingdom, we should “shrink finance, for national prosperity.” Shrink the harmful parts, in red in the left hand image, and keep hold of the good parts.

None of this should even be controversial: the only real argument is about the relative size of each part. As explained above, the “competitive” policies to attract mobile capital to the UK are harmful, because they are of the ‘downgrading’ kind (and anything that might get called “competitiveness” which is beneficial is “upgrading” – so it isn’t “competitiveness.”

Putting all this together, we can rephrase this slogan as “oppose competitiveness, for prosperity.” (We have said this all before, on tax: this is the finance version.)

This broad analysis has profound and optimistic implications for democracy, because it opens up a world of political possibilities for tackling some of the great problems of our age.

Currently, voters and politicians are hamstrung by the Competitiveness Agenda: they may want higher taxes on rich people or on big banks, or stronger regulations to curb financial scandals and abuses – that is, upgrading — but they fear that these people and organisations will disinvest and run away to Geneva, Singapore or Panama, where regulation is lighter. Businesses wield this threat all the time. So nothing gets done, and standards slip.

The race, to many people, looks like a collective action problem, where it is everyone’s shared interests to collaborate, but in the interests of each individual player to cheat. The classic solution to a collective action problem is to co-ordinate and co-operate. Governments get together to agree common thresholds, beyond which they won’t sink, or downgrade. This can work: the OECD programs such as BEPS (to tackle multinationals cheating on their taxes via the international system) or the Common Reporting Standard (CRS) where countries agree to share information on the wealth holdings of rich folk, to improve transparency.

But international collective action is weak medicine. Countries feel the incentive to cheat, it’s also hard to mobilise powerful domestic coalitions to support complex international collaborations – and try getting China or Russia or Luxembourg or Ireland on board in any case.

The finance curse analysis provides a clear and powerful route out of the collective action problem. If we should “shrink finance, for prosperity” – then we can step unilaterally out of the race. We need not wait for international collaborations, in the meantime downgrading our tax laws and financial regulations to stay in the race. The finance curse tells us to do exactly the opposite. Upgrade, chase away the bad actors, and even though the financial sector as a whole will be smaller, the wider economy will be more prosperous.

We can just upgrade, in our own domestic self-interest. This is a far more potent political proposition that can mobilise powerful domestic coalitions behind it.

Has Brexit helped, by shrinking the City of London?

Brexit certainly isn’t the way we would have shrunk the City of London, to boost Britain’s prosperity. But amid all the dark clouds of Brexit, this could be an unintended positive outcome, depending on how this all shakes out. From the EU’s perspective, Brexit also removes a powerful lobbyist that has done much to create harmful regulation in the EU. Europe, too, should take on board the finance curse analysis, as we argued in the Financial Times in2018, and strenuously avoid trying to lure financial activity away from London using ‘competitive’ lures.

Post-Brexit Britain: a global builder or berserking destroyer? The latter currently looks likely. But it is not inevitable.

Much will depend on which faction in the British ruling establishment gets the upper hand, in the years to come.

Related articles

Bled dry: The gendered impact of tax abuse, illicit financial flows and debt in Africa

Bled Dry: How tax abuse, illicit financial flows and debt affect women and girls in Africa

9 December 2025

The millionaire exodus myth

10 June 2025

The Financial Secrecy Index, a cherished tool for policy research across the globe

Inequality Inc.: How the war on tax fuels inequality and what we can do about it

New Tax Justice Network podcast website launched!

The People vs Microsoft: the Tax Justice Network podcast, the Taxcast

Como impostos podem promover reparação: the Tax Justice Network Portuguese podcast #54

Convenção na ONU pode conter $480 bi de abusos fiscais #52: the Tax Justice Network Portuguese podcast

Hello,

Great article but it doesn’t say what an individual member of society can do about it. Are we supposed to sit on our hands and wait for a decent person to do the right thing? If the future of Brexit is of bottom dwelling corporations making us more like the US, I’d rather rejoin the EU.