Alex Cobham ■ The BVI: Responsible for worldwide tax losses of $37.5 billion a year

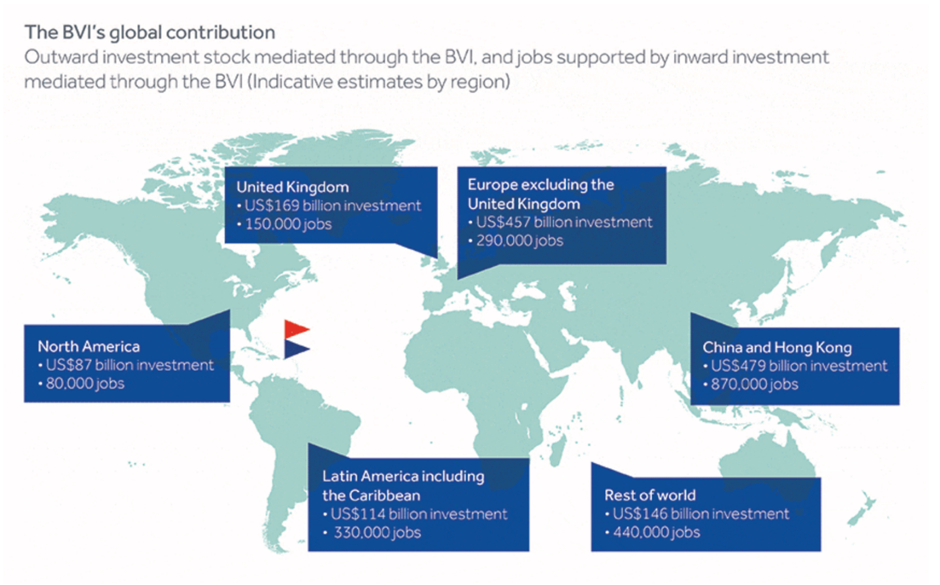

An extraordinary report by consultants Capital Economics, for BVI Finance, claims that the British Virgin Islands are responsible for $1.5 trillion of assets invested around the world, and that these result in 2.2 million jobs and $15 billion in tax revenue. A better approximation would be that the BVI imposes global tax losses of $37.5 billion every year.

Any investments made via BVI could equally go through any other conduit jurisdiction but there is a particular reason why investments go through the small Caribbean nation. It is the anonymity of ownership that BVI sells globally, regardless of the repeated exposure of its entities’ involvement in tax abuses and other forms of corruption and criminal behaviour that is its unique selling point. Not cost or market access, as the report claims, in fact there is little to choose between major financial centres on those metrics. There are also good reasons to avoid investing through a small and unbalanced economy, with questions over both its political governance and the sustainability of its business model.

The claimed .5 trillion of investment routed through the BVI is significantly higher than previous estimates by the likes of the IMF. And so too is the likely cost to the rest of us – not least in lost tax revenues.

Here’s a quick ballpark figure. The leading academic work by Gabriel Zucman (see Table 1) identifies a lower-bound for offshore assets of $7.6 trillion, with a proportion near 80% estimated to be undeclared to tax authorities, giving rise to an estimated global tax loss of $190 billion each year. As a hypothetical, and assuming the same propensity to declare to home tax authorities as Zucman finds elsewhere, the $1.5 trillion in assets claimed for BVI now would suggest that the jurisdiction would be responsible for global tax losses of the order of $37.5 billion.

In other words, the rest of the world is paying around $1.25 million every year for each of the 30,000 inhabitants of the BVI, as a massive subsidy of the islands’ secrecy model. And that’s before we factor in the undoubtedly large, non-tax costs of the corruption that BVI facilitates through its anonymous companies.

Long ago, the UK encouraged its overseas territories down the road of tax havenry, to limit its own responsibilities to provide aid. How much cheaper it would have been for us all, if the UK had invested in productive, sustainable livelihoods for the islanders instead.

Anonymous BVI companies were the majority of the secrecy vehicles uncovered in the Panama Papers, and have been shown to be involved in all manner of tax abuse and corruption cases. The commitment to secrecy was further demonstrated by the BVI government’s repeated granting of a licence to operate to Mossack Fonseca during the 2000s, despite the latter being unable or unwilling to name company owners when required to do so.

If the BVI wants to shed its image as a ‘tax haven’, it shouldn’t waste money paying consultants to claim that it’s not – especially not consultants who recently made similar claims for Jersey. The BVI should instead address the reasons it is viewed as a tax haven – namely, the financial secrecy it provides and should follow the emerging international standard by establishing a public register of the ultimate beneficial owners of all BVI companies and trusts.

The capital economics report was covered in a Financial Times article in which Alex Cobham was quoted from the TJN. The article can be seen here.

The TJN report on the British Virgin Islands, published as part of our financial secrecy index, can be found here.

The original capital economics report can be found here.

Related articles

‘Illicit financial flows as a definition is the elephant in the room’ — India at the UN tax negotiations

Democracy, Natural Resources, and the use of Tax Havens by Firms in Emerging Markets

The Financial Secrecy Index, a cherished tool for policy research across the globe

Do it like a tax haven: deny 24,000 children an education to send 2 to school

Tax Justice transformational moments of 2024

The State of Tax Justice 2024

Indicator deep dive: ‘Royalties’ and ‘Services’

Indicator deep dive: Public country by country reporting

Profit shifting by multinational corporations: Evidence from transaction-level data in Nigeria

5 June 2024