Nick Shaxson ■ Why a ‘competitive’ economy means less competition

From the Fools’ Gold site:

The ‘competitiveness’ of a country can be taken to mean many things. Many people, such as Martin Wolf or Paul Krugman, have argued forcefully that it is a meaningless or dangerous concept. On another level it’s a question of language: you can make national ‘competitiveness’ mean whatever you like.

But there is a very common use of the term out there — what we are starting to call the Competitiveness Agenda — which accepts a particular meaning for the word ‘competitive.’ This agenda involves special pleading to bestow perks such as tax cuts on capital (or on capital owners), on the basis that if they aren’t pampered they will flee to other more hospitable jurisdictions. (Whether they would actually do this is another matter: the point here is that the scaremongering is often effective in securing pork for capital.)

The special pleading goes along the lines of: “give us this tax perk and your whole economy will be more ‘competitive.’ ”

Remember that ‘competition’ between (and the ‘competitiveness’ of) countries bears absolutely no relation to competition between private sector actors (like companies) in a market. To grasp this, ponder the differences between a failed company that can’t compete, and a failed state.

The basic argument of today’s post is that the Competitiveness Agenda will tend to reduce competition in markets where it is pushed.

How so? Well, it’s pretty simple.

The firms that are most able to flee (or partly flee) to foreign jurisdictions are (naturally) the internationally-focused ones. That usually means multinational corporations — and that tends to mean big corporations. The locally-focused ones, which are most wholly embedded in the local economy and won’t flee, are generally the smaller firms.

So the Competitiveness Agenda will tend to give large multinationals advantages over smaller firms (over and above the advantages they already enjoy, such as economies of scale), enabling them to kill the smaller firms on factors (like getting particular tax breaks) that have nothing to do with genuine wealth creation and everything to do with wealth extraction.

End result: the big get bigger, and smaller firms die. There is less competition in markets.

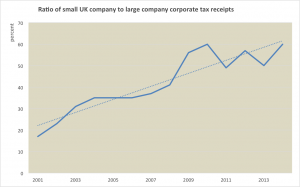

Here’s a visual graphic to illustrate the process in action recently.

This graph shows how the tax burden on large companies in the UK has fallen relative to the tax burden on small companies. (Click to enlarge: find the data sources for that graph, and further explanations, here).

This graph shows how the tax burden on large companies in the UK has fallen relative to the tax burden on small companies. (Click to enlarge: find the data sources for that graph, and further explanations, here).

Though there are other reasons for this dramatic slope, ‘competitive’ changes to the UK corporate tax system have been a big contributory factor: the headline tax rate for big corporations has fallen by over a third, from 28 to 18 percent, while the small company tax rate has hardly budged (it was 21 percent, then was unified with the main rate at 20 percent; and the unified rate is due to fall to 18 percent by 2020).

A ‘competitive banking sector means monster banks

Now the same generic process is underway concerning the UK’s big globe-trotting behemoth banks like HSBC, and smaller ‘challenger’ banks which the government says it is keen to promote. The International Tax Review (ITR) describes this in an article entitled UK Financial Sector Pushes Back against Punitive Tax Policy:

“A financial sector backlash against UK tax changes continues to grow as revenue figures become clearer. The changes, announced by George Osborne, Chancellor of the Exchequer, in July’s summer budget, include a new 8% surcharge that will be applied, from the beginning of 2016, to bank profits above £25 million, while the UK’s bank levy will be gradually phased out.

(The official explanation of the changes is here: the detailed budget policy costing are here on p16, although for some reason they won’t break down the impacts of the two separate tax changes.)

To summarise, two things are happening here.

- One tax — the bank levy — is going down. Crucially, it’s going down due to ‘competitive’ pressures: as Bloomberg summarises:

“the chancellor pared the levy on banks’ assets, bowing to pressure from lenders that have threatened to leave London.”

Until now, only the biggest 30 or so banks in the UK paid the levy: costing them over £8bn since it was introduced in 2010 in the teeth of financial and economic crisis.

- Another tax — the new 8% surcharge, which will apply also to smaller “challenger banks” and building societies that are currently exempt from the existing bank levy — is going up. This will spread the tax net to 200 or so banks, with only the very smallest falling under the £25 million threshhold.

(It may be telling that in the official explanation for the bank levy, and even in the detailed budget policy costings, the government has not broken down the revenue impact into its two components. We’ve submitted a Freedom of Information report and will let you know the result here.)

Fortunately, the UK’s financial press and some politicians have noticed what’s going on. The publication City A.M., normally a cheerleader for the big banks, has an article by Labour Party official Alison McGovern MP entitled George Osborne’s damaging bank tax changes are a blow to competition in the sector. She wrote that the twin moves

” . . . will act as a tax rise for small challenger banks and building societies, who pose less risk to our economy, while the big international banks get a much better deal. It risks stifling competition and acting as a restraint on sensible lending. . . a responsible government would be trying to promote more competition in the sector.“

Our emphasis added.

This, of course, reflects exactly the same generic process that’s been driving the UK headline corporation tax rate changes: a falling burden on big players, and a rising burden on smaller ones. Overall, it will tend to kill the smaller players.

In short: a ‘competitive’ tax policy for the financial sector means reduced competition in banking. And, as one of many other side effects, more dominant monster banks which pose still greater threats to financial stability.

Endnote: We aren’t necessarily arguing that competition in the financial sector is always a good thing: if, for example, banks ‘compete’ to take ever greater risks at the taxpayers’ expense, this can result in overall harm. The point of our post is to describe and illustrate the generic point that the pursuit of national ‘competitiveness’ and the Competitiveness Agenda is generally likely to reduce competition in markets.

Related articles

Bled dry: The gendered impact of tax abuse, illicit financial flows and debt in Africa

Bled Dry: How tax abuse, illicit financial flows and debt affect women and girls in Africa

9 December 2025

The millionaire exodus myth

10 June 2025

The Financial Secrecy Index, a cherished tool for policy research across the globe

Inequality Inc.: How the war on tax fuels inequality and what we can do about it

New Tax Justice Network podcast website launched!

The People vs Microsoft: the Tax Justice Network podcast, the Taxcast

Como impostos podem promover reparação: the Tax Justice Network Portuguese podcast #54

Convenção na ONU pode conter $480 bi de abusos fiscais #52: the Tax Justice Network Portuguese podcast