Nick Shaxson ■ What might Brexit do for tax havens and tax justice?

The UK votes on Thursday in a referendum over leaving the European Union. While there are dynamics that play in different directions, such a ‘Brexit’ would almost certainly see the UK itself push further down the road of tax havenry, hurting its own citizens and causing wider global damage.

The tax injustice effects

The most obvious effect, in Britain, is illustrated by this quote from Rupert Murdoch, arguably Britain’s most influential media magnate, via the journalist Anthony Hilton.

[For non-UK readers, “Downing Street” is shorthand for the British Prime Minister’s residence.] And Murdoch isn’t alone: the Daily Mail, Britain’s biggest selling newspaper, is owned through tax haven interests. And see also this new Richard Smith post for Naked Capitalism, which raises some interesting tax haven questions about the “Leave” campaign and some of its leading lights. For instance:

Leave.EU, which has been backed by the UK Independence party (Ukip) leader, Nigel Farage, and describes itself as “Britain’s fastest growing grassroots movement”, was incorporated in the United Kingdom as a wholly-owned subsidiary of a finance firm based in low-tax Gibraltar that specialises in “international wealth protection”.

Now, on a different tack, here is a fascinating discussion by Adam Posen, President of the Peterson Institute for International Economics and a well known economist, rhetorically putting the pro-Brexit line.

“My concern is, in part based on comments by the leadership of the pro-Brexit vote, is that they essentially double down on being a financial center. That they say ‘We want to be the offshore financial center for Europe. Oh look, the Chinese are going to start trading renminbi in London, it’s going to be great.’ “

(We have written plenty about the risks of London and Renminbi trading.) Then Posen brings up what is, essentially, our Finance Curse argument: more finance is bad for your country.

“That [oversized finance ha]s actually not done very well for the UK in recent years. As Mervyn King used to say, this has completely unbalanced the British economy. That’s why you have such wealth and such concentration in London, and such relative impoverization of other industries and other regions in the UK. It’s just a huge distortion, it tends to overvalue the currency, it tends to move things the wrong way on the current account, it’s very bad.

Second, despite what Governor Carney said a couple of years ago about being willing to have bank balance sheets at 900% of GDP, the fact is – as Iceland and Ireland and Portugal – have shown, it’s not a good idea to have banks that are many, many times larger than your GDP: because you’re left holding the bag as taxpayers if something goes wrong. So if the UK goes down this avenue, they are just exposing themselves more and more to future risk.”

And then, with this preamble, Posen delivers a spectacularly tax justice-ish quote:

If you’re anti-regulation fantasists to begin with, you start going down the path, ‘Oh we can become an even more offshore center. We can become the Cayman Islands writ large, or Panama writ large.’ And this frankly is the way I think this also spills over to the rest of the world, is that the UK decides, ‘Hey, regulatory arbitrage, letting AIG financial products run in London, actually destroyed the US financial system, but didn’t hurt us – made us a lot of money. Let us continue down this path. Let us be the ‘race to the bottom’ financial center. And I think this that’s where this going, because they’re not going to have any other option. It’s not good.

On a much smaller level, there are also some specific tax justice proposals where the UK has played a useful positive role: not least a pledge by UK Chancellor (finance minister) George Osborne to support our proposal of public country-by-country reporting by multinational. Brexit would curb this influence.

Brexit, in our summary, would be likely to be a boon for tax havens, a bane for progressive taxation and transparency, and a boost to further financial deregulation, and the impunity of tax evasion and corruption of the type revealed in the Panama Papers.

Storm clouds have silver linings

But this negative story has a more positive flip side too. If Brexit is likely to be bad for tax justice in Britain, it may from this particular perspective have positive tax justice implications in Europe. Take a look at this report from Corporate Observatory Europe entitled How Cameron’s referendum delivered victories to Big Finance. The summary gives the general idea:

“From the day a referendum on UK membership of the EU was first announced in 2013, the financial sector started using Cameron’s re-negotiation process to promote its deregulatory agenda. Sometimes lobbying was required, but more often the UK government did its work for them.”

(Read the report for details.) Financial sector dominance is generically bad for tax justice – and many big banks oppose Brexit, quite fiercely. The corollary of this would be that if Britain left Europe, the City of London would lose influence in Europe (and probably shrink in size at home) and a different, more progressive financial agenda might become possible, at least in Europe. Britain would be in less of a position to remove its Overseas Territory of Bermuda, for instance, from EU blacklists. Meanwhile, Europe would still be in a position to demand many concessions from Britain, in exchange for British businesses being allowed access to the EU’s giant single market. Tax justice campaigners would surely work hard to put our concerns into that mix of conditionality.

And let’s be honest: while the European Union has in general terms served as a progressive, democratic brake on many of the nastier anti-poor elements in British politics, it has been no tax justice nirvana, not least thanks to the vicious little European tax haven of Luxembourg: the latest Euroshambles on corporate tax, and the role of former Luxembourg Prime Minister Jean-Claude Juncker as President of the European Commission, are reminders of this. The European Court of Justice, in the Cadbury Schweppes case — which has made it harder to for tax authorities to crack down on multinational tax shenanigans — are also reminders that Europe can act in the wrong direction.

The crisis angle

Another factor to consider – though not to predict – is that Brexit would, in the view of many economists, cause a deep economic crisis in Britain and in Europe.

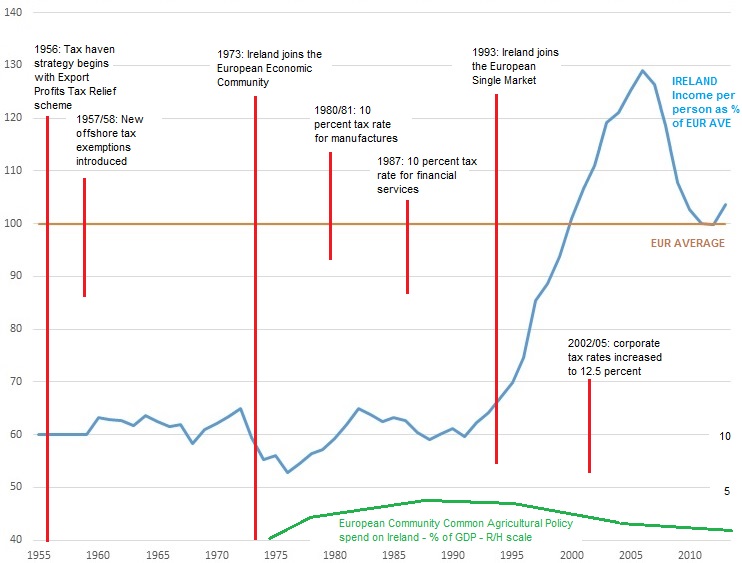

We have very few precedents to draw on, in terms of countries leaving trade blocs. So we’ll show you instead a picture of what happened to one country – Ireland – when it went into the EU. This graph for Fools’ Gold was originally created to show how ineffectual corporate tax games seem to have been in driving Ireland’s post-1990 growth, and to identify the real core driver of the (now battered and bruised) Celtic Tiger. But it is certainly instructive for would-be Brexitists.

Chart 1: Ireland’s GNP per capita, relative to European GNP per capita, 1955-2013.

This doesn’t of course prove that Brexit would cause a crisis, though there are multiple reasons for thinking it would, as a bunch of Nobel-winning economists just warned. In Ireland’s case, entry turned it into a friendly English-speaking platform for entry into huge European markets. Britain would see the opposite effect.

Although crisis can sometimes be the handmaiden of new forms of politics, those forms frequently can be very nasty indeed.

Overall: Remain is the safer bet

Brexit is a recipe for the race to the bottom. That is the exact antithesis of tax justice.

The EU has problems, for sure – but progress towards common transparency measures for a fairer politics depend on countries collaborating, not the false ‘competition’ of a tax haven race to the bottom.

If there’s a tax justice vote on Thursday, it’s a vote for the UK to Remain.

Title image by Jamie Street on Unsplash

Related articles

New Tax Justice Network podcast website launched!

Como impostos podem promover reparação: the Tax Justice Network Portuguese podcast #54

Convenção na ONU pode conter $480 bi de abusos fiscais #52: the Tax Justice Network Portuguese podcast

As armadilhas das criptomoedas #50: the Tax Justice Network Portuguese podcast

The finance curse and the ‘Panama’ Papers

Monopolies and market power: the Tax Justice Network podcast, the Taxcast

Tax Justice Network Arabic podcast #65: كيف إستحوذ الصندوق السيادي السعودي على مجموعة مستشفيات كليوباترا

Remunicipalización: el poder municipal: January 2023 Spanish language tax justice podcast, Justicia ImPositiva

Hoja de ruta para un cambio en toda América Latina: December 2022 Spanish language tax justice podcast, Justicia ImPositiva

All will depend on the trade deal with the EU. UK can gain a lot or lose all.