Nick Shaxson ■ Bono: Tax Haven Salesman for the Celtic Paper Tiger

We’ve been (almost) biting our TJN tongues on Mr. Bono’s latest outburst since the weekend. We were waiting for this to come out. Cross-posted from Naked Capitalism, with permission. We’ve tweaked a couple of words here and there.

Bono: Tax Haven Salesman for the Celtic Paper Tiger

By Nicholas Shaxson

Paul Hewson, an Irish crooner who likes to go by the name of Bono, is well known for calling on citizens to spend their tax dollars on fighting poverty in Africa – then setting up fancy structures to dodge paying his own taxes. The British celebrity entertainer Graham Norton skewers Bono effectively:

People like Bono really annoy me. He goes to hell and back to avoid paying tax. He has a special accountant. He works out . . . tax loopholes. And then he’s asking me to buy a well for an African village. Tarmac the road outside your house, you tight-wad!

Selfishness and hypocrisy are one thing.

Economic illiteracy is another. Bono’s just been speaking out again in Britain’s Observer magazine:

“The Irish singer says his country’s tax policies have “brought our country the only prosperity we’ve known”. Bono said: “We are a tiny little country, we don’t have scale, and our version of scale is to be innovative and to be clever, and tax competitiveness has brought our country the only prosperity we’ve known.

“That’s how we got these companies here … We don’t have natural resources, we have to be able to attract people.”

It is impressive how much nonsense can be crammed into so few words. Where to begin?

Let’s start with ‘competitiveness.’

Whole countries don’t compete on tax – at least not in the way Bono means it.

To illustrate this, consider what the end point is of a fatal loss of competitiveness, first for a company, and then for a country.

For a company, the end point is likely to be that it goes out of business, and disappears. The creative destruction involved, for all the pain involved, can be one source (among several) of the dynamism of markets.

But for a country, what is the logical end point of a fatal loss of competitiveness? A failed state?

No: clearly we are dealing with completely different beasts here. Companies competing belong in the field of microeconomic theory; the process of nation states engaging in a race to cut corporate tax rates is a politically driven process of beggar-thy-neighbour self-interest that bears no useful relationship to what companies do. Unfortunately, these two very different processes share a word in the English language: “competition” – so Irish singers, and many others, confuse and conflate the two.

That first confusion of Bono’s is doubly relevant here, because he regularly excuses his own abusive tax shenanigans by cloaking himself in Ireland’s “clever” tax games. Just how clever they are, we’ll soon see.

The precise words Bono used here, though, were not ‘competition’ but ‘tax competitiveness.’

Here he unveils at least two more illiteracies.

The first is the fallacy of composition. What is good for a corporation isn’t necessarily what is good for a country that hosts that corporation – especially when those goodies are extracted from that country by that corporation.

Tax is not a cost to an economy, but a transfer within it. So it’s not immediately obvious that a corporate tax cut – taking wealth away from public investment programmes and giving it to (often foreign) shareholders will make your economy more “competitive,” whatever that word means. Is a new factory more productive than a new road or a bunch of teachers’ salaries?

In response to this, Bono replies that tax cuts also attract business. “That’s how we got these companies here,” he pleads.

But is this even true?

The shortest answer is “no.” A slightly longer answer is: “it depends what you mean by ‘business.’ And here we get into the next layer of illiteracy.

When politicians (and, presumably, singers) talk about a need to seek foreign investment, they always mean the kind that brings jobs, supply chains, knowledge, and other good stuff: genuinely productive business, embedded in the local economy.

But ‘business’ that is sensitive to tax is – by definition! – flighty, and therefore not embedded in the local economy. So tax cuts generally bring the stuff that is least useful: unproductive profit-shuffling, that bring few jobs or real investment.

In fact, survey after survey shows that what brings foreign investment to a country is, above all, the rule of law, a healthy and educated workforce, good infrastructure, courts, and stuff like that. These require tax dollars. For genuine investors, tax breaks are nice, but not necessary, as one businessman summarised:

“I never made an investment decision based on the tax code…If you are giving money away I will take it. If you want to give me inducements for something I am going to do anyway, I will take it. But good business people do not do things because of inducements.”

And who, pray, was this screaming left-winger?

Step forward Paul O’Neill, the former chairman of Alcoa and former Treasury Secretary under George W. Bush. (And on the subject of Bono and Paul O’Neill, take a look at this little nugget.)

Tax breaks can help attract some activity, at the margin, but aren’t that important. If you’ve given away your educational system to attract those marginal investors, that may well be a price too high to pay. Prof. Jim Stewart of Trinity College, Dublin, one of the only “tax dissident” public intellectuals in Ireland otherwise heavily captured by tax accountants and financial services interests, looks at this from a different angle, writing in the Financial Times recently:

A tax-based industrial policy will not produce an innovative economy at the cutting edge of technology and research.

It’s essential to add that it’s not Ireland’s headline 12.5 percent tax rate that is the big lure: it’s complex, the loophole-riddled tax system, which generally involve Ireland deciding what portion of profits doesn’t get taxed at that low rate. Stewart adds, via email:

The only people who understand these incentives are those working for the Big Four, who become large and powerful and exert considerable influence on government to extend and introduce new reliefs. Tax minimsation strategies dominate corporate decision making to the detriment of what is really important.

‘Ah’, I can hear Bono replying, ‘but Ireland has created real jobs in pharma and other high-tech sectors! So there!’

Not so fast, Mr. Hewson.

First, tax isn’t the driving force behind Ireland’s celebrated ‘Tiger” economy, no matter what the politicians and Irish tax-hype industry tell you. Far from it.

The big reason U.S. tech companies “locate” in Ireland is that it is a unique, culturally connected and English-speaking gateway for U.S. multinationals into the Eurozone. There are tax-related jobs and investment in Ireland, to be sure – but if Irish people spoke Latvian the country would see a tiny fraction of this, if anything. It’s a bit like Hong Kong’s success on the back of its role as a unique English-speaking gateway to China.

There’s nothing “clever” about this, Bono: it’s just history and geography, really.

The data clearly supports this. Look at the timing of when it all happened.

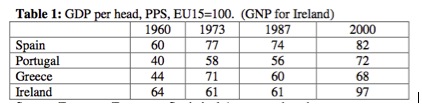

Ireland’s policy of trying to be a tax haven started in 1956, long before other European countries got into the game. Yet from the 1960s all the way to the 1990s, Ireland’s GNP per capita stubbornly stuck at just 60-65 percent of the EU average, even as Spain, Greece and Portugal saw theirs rise sharply. (And yes, Virginia, Ireland most certainly, absolutely is a tax haven.)

Source: Irish Economic Development Over Three Decades of EU Membership, Frank Barry, August 2003

It’s the period around the introduction of the European Single Market in 1992 when Irish growth took off. That, not the tax breaks, was what did it. (One might also describe this as a story about “catch-up” – or, in Ireland’s case, delayed catch-up – after entering the club.)

A second big reason for Ireland’s success in that era is the huge European transfers showered on it, notably since the doubling of EU infrastructural and cohesion funds in 1989, equivalent to 3 percent of GDP per annum, and agricultural subsidies worth 4 percent of GDP by the mid 1990s. Agriculture, broadly defined, produces about the same value added as multinational corporations do. These transfers directly fed Irish growth, and helped attract back many expatriate members of the Irish diaspora, educated on the back of someone else’s tax dollars.

A third reason for Ireland’s headline economic growth since the 1990s was that it has been peddling a cocktail of wild-west lax financial regulation. The Irish Financial Services Centre (IFSC), set up in 1987 under the “voraciously corrupt” Irish politician Charles Haughey, allowed firms from Wall Street and the City of London to gorge for years on a lack of scrutiny and lax financial regulation ahead of the financial crisis. (Read more about that sordid tale here.)

Tax was not a mainstay of this policy, which did have a measurable impact on headline Irish growth figures. But here’s the rub – and a fourth thing to say about the Celtic Tiger.

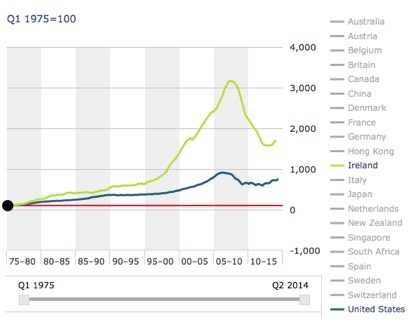

As we now know, the global financial crisis exposed it as a (mostly) paper tiger. The crisis affected Ireland worse than most; the sheer local pain of the crash has been masked by the pressure valve of massive Irish emigration, but it is surely the worst recession has endured in a century. The boom that preceded the crash was predicated heavily on a house price boom that puts many other booms into the shade, as The Economist’s House Price Index shows:

Bono may think this is an example of Ireland being “clever.”

If that isn’t enough for Mr. Hewson to digest, there’s more.

Ireland’s tax policies not only haven’t been remotely as successful as the lobbyists claim: it has effectively been pursuing a policy of trying to get rich by picking other countries’ pockets. (It’s a bit like popular musicians picking the pockets of their fellow taxpayers, while asking them to fork out for a well in an African village.)

Clever, perhaps, but only for some. And when you put in place tax policies like this, other countries respond.

Some bite back with attacks and opprobrium and sanctions, as the European Commission is now doing, with respect to some of its tax policies, potentially unravelling a cornerstone of Ireland’s offerings. A cowed Ireland, fresh from last year’s mauling in the U.S., is now considering abandoning one of its most famously abusive offerings: the “Double Irish” loophole.

A rising tide of public outrage and political will sustain the pressure on Ireland. Its strategy isn’t sustainable, even on its own terms.

And there’s another problem here. When you engage in a race to the bottom, others bite back in a different way: by trying to out-loophole you. The United Kingdom has been putting in place its own foolish, nasty, disingenuous and hypocritical corporate tax offerings, in the hope that by bowing down to mobile capital in a sufficiently prostrate fashion, some corporate bosses will shuffle a few profits in its direction. Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Switzerland, Belgium, Gibraltar, Bermuda, and many others: they are all at it too.

The process that ensues as more and more join in is a classic race to the bottom, more akin to currency wars than to anything one might call ‘competition.’ Bono is casting himself as a popular cheerleader for this kind of economic warfare.

(As an aside, people must really stop using the traditional term ‘tax competition’ here and begin using the more economically literate term: tax wars, just as Brazilians say Guerra Fiscal to describe the jostling on tax that happens inside their federation.)

Mr Bobo digs a yet deeper hole for himself when he says stuff like this:

As a person who’s spent nearly 30 years fighting to get people out of poverty, it was somewhat humbling to realise that commerce played a bigger job than development.

I do struggle to picture Bobo feeling humble.

More importantly, though, he is mixing ‘commerce’ (and, elsewhere, he’s said ‘business’) with ‘profit-shuffling’.

It’s true that “development” in poor countries doesn’t need to mean doling out aid. But it most certainly does mean allowing poor countries to be able to tax multinational corporations effectively – something Bono seems to be opposing.

Even Bobo’s band mates don’t seem to agree with his woolly thinking, as the bit in bold here suggests:

“At the band’s headline gig at the 2011 Glastonbury festival, a small lobby of audience members waved banners protesting about the issue. U2’s guitarist, the Edge, said: “Was it totally fair? Probably not. The perception is a gross distortion. We do pay a lot of tax. But if I was them I probably would have done the same.”

Related articles

The millionaire exodus myth

10 June 2025

The Financial Secrecy Index, a cherished tool for policy research across the globe

Inequality Inc.: How the war on tax fuels inequality and what we can do about it

New Tax Justice Network podcast website launched!

The People vs Microsoft: the Tax Justice Network podcast, the Taxcast

Como impostos podem promover reparação: the Tax Justice Network Portuguese podcast #54

Convenção na ONU pode conter $480 bi de abusos fiscais #52: the Tax Justice Network Portuguese podcast

Can the UN succeed? Top questions about our State of Tax Justice report

As armadilhas das criptomoedas #50: the Tax Justice Network Portuguese podcast