UN tax convention

Right now, our governments are negotiating the biggest shakeup in history to global tax rules at the UN. The outcome of these talks – a world-first UN tax convention – will impact every one of us, wherever we are in the world, and shape people’s lives for generations to come.

It’s not just trillions of dollars on the line, but our democracies, human rights and planet.

The Tax Justice Network is working alongside campaigners, experts, policymakers and investors from around the world to help achieve the best outcomes for people, economies and planet.

What you’ll find on this page

Whether you’re just learning about the UN tax convention or are deeply involved in the negotiations, we’ve designed this page to get you the information you need.

Here’s what’s below:

⏱️60-second newcomer crash course New here? Start here. ↴

🔔Latest news The latest on the convention. ↴

🧩Build-a-Convention tracker What’s gone in and what still needs to go into the convention? See the latest negotiation updates. ↴

🛒“Who wants what?” database See what countries have said they want on specific policy issues under the convention. ↴

✊“Tax justice ABCs” in the convention The policies that make tax systems work for everyone equally, not just for the superrich or the Global North. ↴

📢Social justice in the convention Securing a UN tax convention for gender rights, human rights, climate justice and education. ↴

⏱️60-sec crash course

👋New here? Start here 👉 What’s the UN tax convention?

🔔Latest news: Fourth Session of UN negotiations underway

13 Feb 2026 5:33pm GMT – Fourth session of negotiations conclude

And that’s a wrap, folks! The fourth session of negotiations have come to an end. A big thank you to all of you who followed along with us. We’ll be sharing more updates next week, with reflections on what’s happened and what’s next. If you found our updates and resources useful and would like to support us to continue this work, please consider a donation to the Tax Justice Network if you can afford it – alternatively, sharing our content online is a huge help too. Have a good weekend, all!

13 Feb 2026 3:31pm GMT – Last day of negotiations (day 9) starting

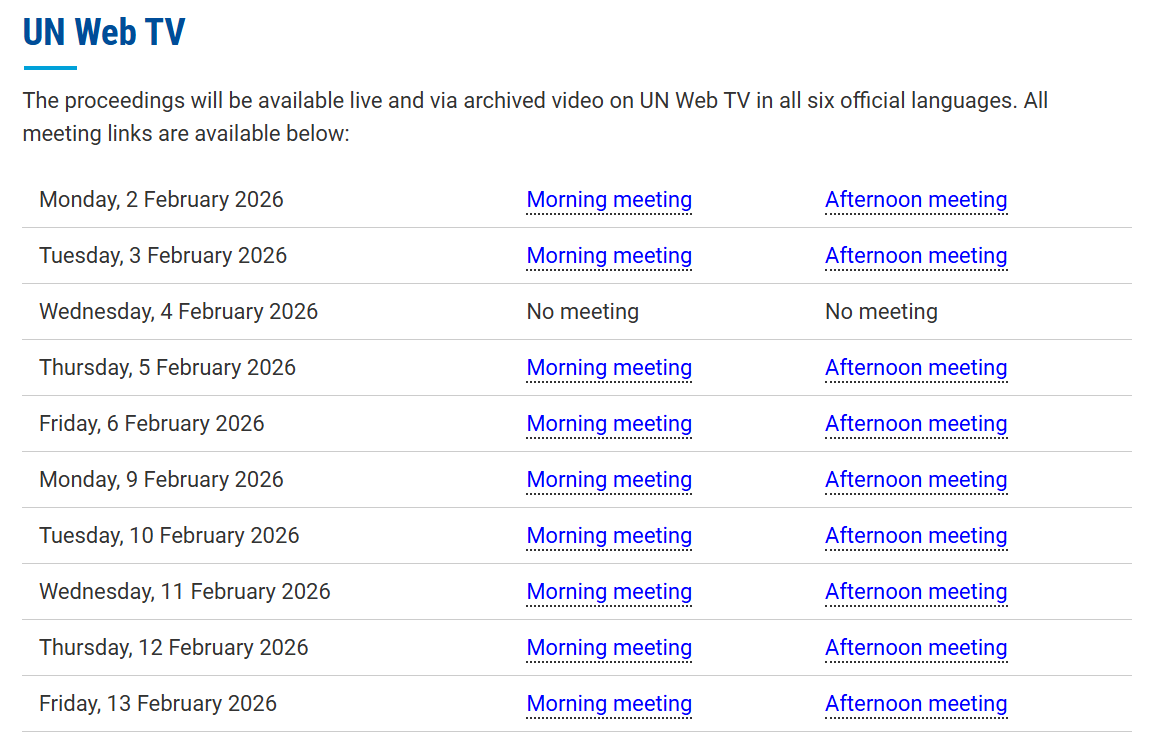

It’s been a long, historic and exciting two weeks. The final day of this fourth session of negotiations is now underway. You can follow the negotiations live on UN Web TV (or watch it below) and find the full schedule here.

12 Feb 2026 2:21pm GMT – Detailed summaries on three days of negotiations on Protocol 1

Yesterday saw the end of three intensive days of negotiations on Protocol 1 on cross-border services. We’d upload detailed summaries for each of these days, which you can find further below on this page in our “Build-a-convention” section.

📌PINNED: 4 Feb 2026 5:00pm GMT – Statement by the chair of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee

Over the past two days of UN tax convention negotiations, a few countries have made interventions that fail to acknowledge the documented failures of the global tax systems and the accounts from developing countries about how the system’s built-in unfairness harms their economies and people. Just a few minutes ago, the chair of the UN tax convention’s Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee, Mr. Ramy Youssef, delivered some refreshingly sharp facts about the realities of the global tax system, the challenges developing countries face and what the UN tax convention must achieve. It’s worth watching in full.

📌 PINNED: 2 Feb 2026 12:05pm GMT – EU losing 5 times Greenland’s GDP to Trump’s tax conquest, experts warn as UN tax talks resume

Without any public debate, EU countries have agreed to exempt US multinationals from most of the elements of the global minimum tax – when the tax dodging of those same US multinationals costs the bloc €14 billion in lost revenues each year. We’ve published a new briefing this morning warning European countries that the UN tax talks are their last chance to defend their tax revenues and their people’s tax rights, for at least a generation. Read the press release here and briefing here.

Older updates

12 Feb 2026 1:37pm GMT – ICRICT post on formulary apportionment

The International Commission for the Reform of International Corporate Taxation have shared the following post on why multinational tax rules need a formulaic approach at the UN.

12 Feb 2026 10:55m GMT – Tax experts slam ICC for “shameless” facts-for-hire report on UN tax proposal

Leading tax experts have slammed the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) over a “shameless” report in which the ICC used a deeply flawed model to unfavourably depict a UN tax proposal as harmful to global South countries.

José Antonio Ocampo, a commissioner of the International Commission for the Reform of International Corporate Taxation (ICRICT) and the former Finance Minister of Colombia, said:

“It is disappointing to see such a flawed analysis being used to justify lobbying at the UN negotiations. And it is disturbing to see that so many OECD countries appear to want to endorse this report, apparently without any kind of due diligence.”

Alex Cobham, chief executive at the Tax Justice Network, said:

“The ICC’s report is a shameless attempt to muddy the debates at the UN. The report’s deeply flawed claims are unfit for this level of international negotiations and disrespectful to the time and intelligence of countries’ delegations. These kinds of facts-for-hire tactics might have passed in the closed-doors haggling at the OECD, but now that global tax rules are being publicly negotiated at the UN, we can better separate fact from fiction.”

Read the full press release here.

10 Feb 2026 3:35pm GMT – Day 6 of negotiations underway

Negotiation are underway. You can follow the negotiations live on UN Web TV (or watch it below) and find the full schedule here.

10 Feb 2026 11:38am GMT – What Kwame Nkrumah knew about profit shifting

From colonial accounting tricks to modern tax havens, Nkrumah understood how capital escapes, and why political independence was never enough. Read the blog we’ve published this morning by Rachel Etter-Phoya, originally posted by Africa Is a Country.

“If Nkrumah were alive today, there’s no question he would be backing another attempt to break Africa free from old rules that only work for their old masters. As he wrote, ‘With economic unity, [of] countries in Africa […]. We would all be in a better bargaining position […] to establish adequate taxation of foreign factor earnings. In fact, a whole new pattern of economic development would be made possible.'”

9 Feb 2026 5:10pm GMT – Negotiation summaries on Article 10 and Article 12 added

We’ve now added detailed summaries of Friday’s negotiations on Articles 10 and 12 – apologies for the delay on these! Scroll down to our “Build-a-convention” section below to see the new updates.

9 Feb 2026 3:25pm GMT – Day 5 of negotiations begins

Negotiation are about to resume following the break over the weekend. Delegates are finding their seats and the negotiations should get started shortly. You can follow the negotiations live on UN Web TV (or watch it below) and find the full schedule here.

9 Feb 2026 3:25pm GMT – Korean President Lee becomes first head of state to call out “millionaire exodus” myth, citing Tax Justice Network research debunking the myth

In separate news but relevant tax policy, South Korean President Lee Jae Myung condemned the Korea Chamber of Commerce and Industry over the weekend for spreading “fake news” about millionaires supposedly leaving South Korea due to inheritance taxes after the Chamber cited in a press release the widely discredited Henley & Partners report. The President cited the Tax Justice Network’s 2025 debunking of the report, which criticised the report for enabling “scaremongering” against wealth taxes. Read more about this huge development here.

6 Feb 2026 3:25pm GMT – Day 4 of negotiations begins

Negotiation are about to begin. You can follow the negotiations live on UN Web TV (or watch it below) and find the full schedule here.

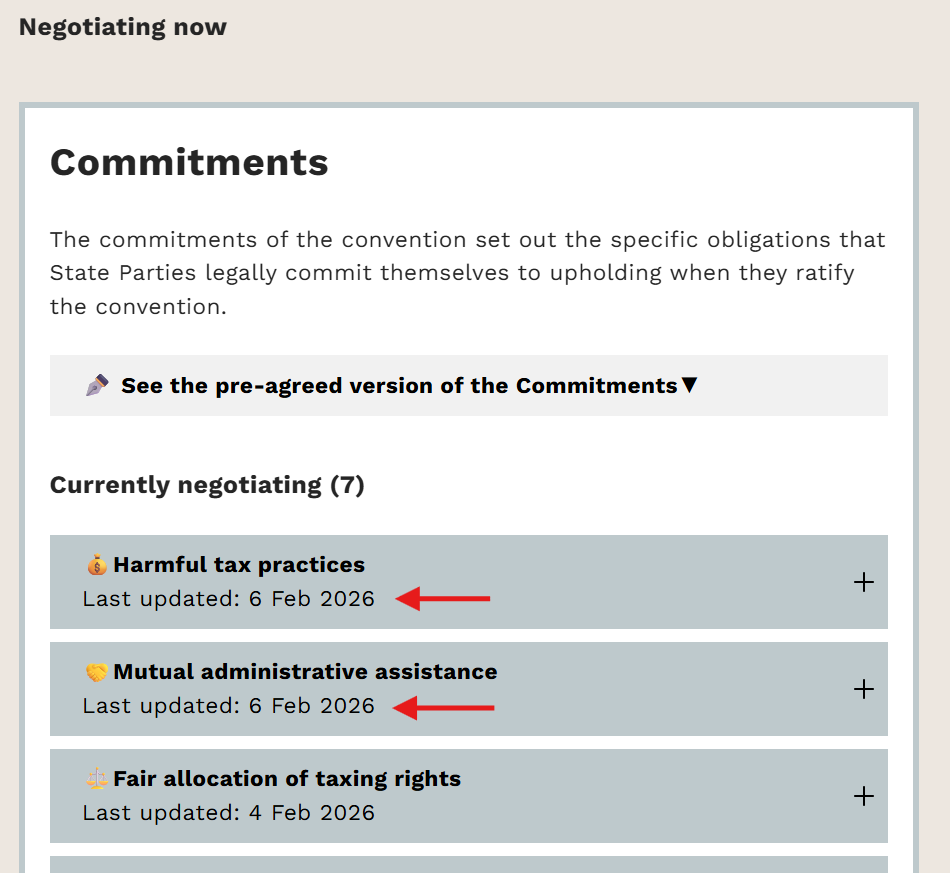

6 Feb 2026 11:50am GMT – New summaries added on yesterday’s negotiations of harmful tax practices (Article 8) and mutual administrative assistance (Article 9)

Scroll down to our “Build-a-convention” section below to see our new detailed updates on yesterday’s negotiations of these two articles.

5 Feb 2026 4:55pm GMT – Transcripts of India’s and Norway’s proposals on Article 8 (Harmful tax practices)

India and Norway have verbally shared proposals on Article 8 on harmful tax practices. We are sharing here the current draft of the article (as prepared by the Co-lead) followed by our transcripts of India’s and Norway’s proposals.

Current draft (Co-lead’s draft as of 22 Jan 2026)

- The States Parties shall develop, enhance and implement effective tools to address harmful tax practices including tools that provide for:

(a) enhanced transparency;

(b) monitoring and identifying emerging harmful tax practices; and

(c) the effective taxation of economic activities that benefit from harmful tax practices. - The States Parties shall cooperate, at international and regional levels, to identify and deter harmful tax practices to neutralize their distortive effects and enhance the ability of all countries to tax income in accordance with their domestic laws and policies.

India’s proposal

As read out by the delegation and transcribed by Tax Justice Network staff:

- The State Parties agree to develop and apply common principles and standards to identify HTP that distort crossborder taxation or erode the tax base of other jurisdictions.

- The State Parties agree to develop, enhance and implement effective tools and measures that provide for monitoring and identifying HTP.

Norway’s proposal

As read out by the delegation and transcribed by Tax Justice Network staff:

The State Parties shall cooperate at international and regional levels to identify, monitor and deter HTP including emerging HTP, promote transparency and enhance the ability of all countries to tax income in accordance with their domestic laws and policies.”

5 Feb 2026 3:15pm GMT – Day 3 of negotiations begins

After yesterday’s break, negotiation’s are now resuming. Delegates are filling the room and the morning session will kick off shortly. You can follow the negotiations live on UN Web TV (or watch it below) and find the full schedule here.

5 Feb 2026 2:02pm GMT – Joseph Stiglitz key note address from yesterday’s Special Meeting

Negotiations will be resuming in an hour today after yesterday’s break. A Special Meeting by the Economic and Social Council was held yesterday, which you can rewatch here and find clips from in our updates further below. Here’s the high-level key note address by Joseph Stiglitz from the meeting.

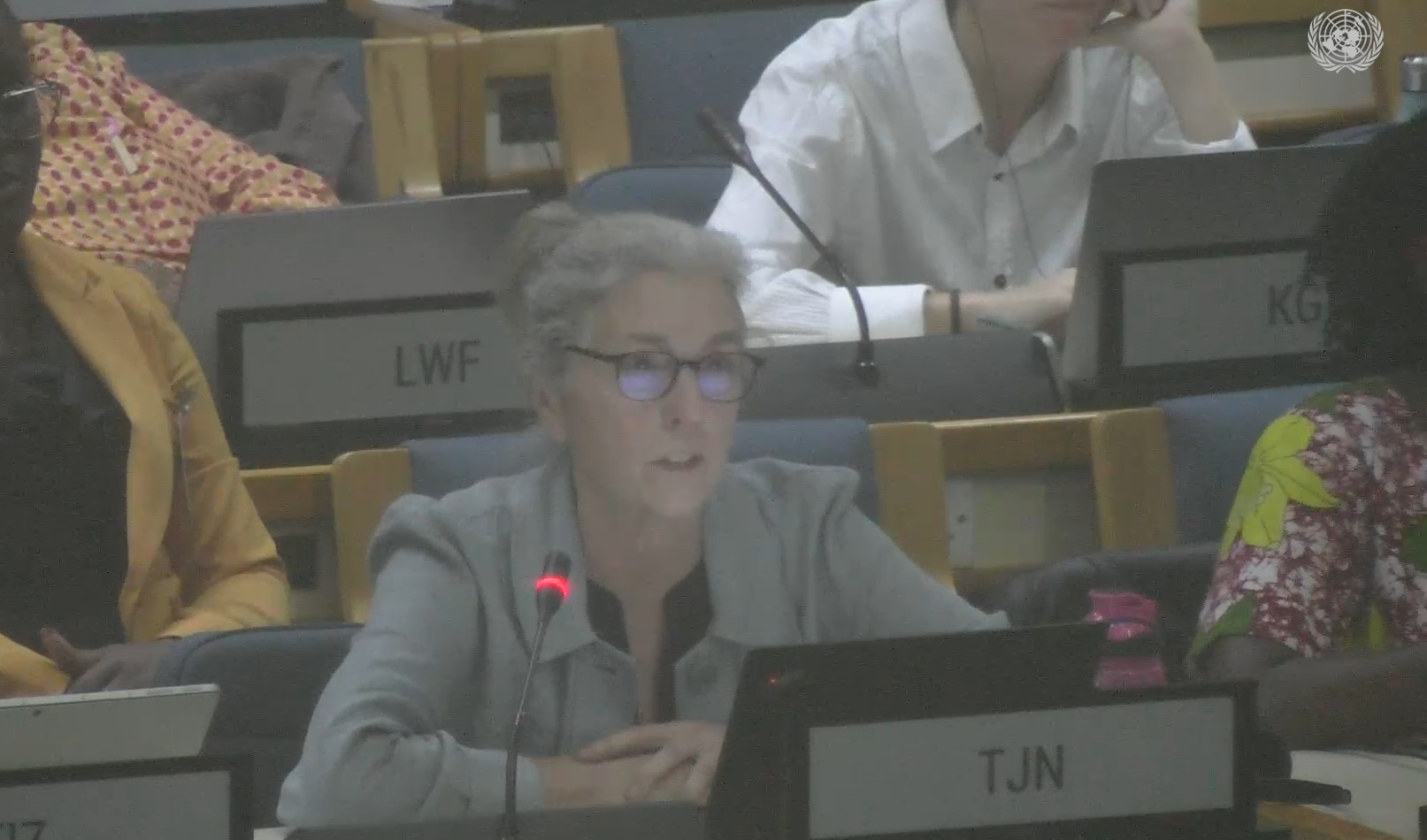

4 Feb 2026 5:55pm GMT – Tax Justice Network director’s statement on tax transparency and tax sovereignty

Our Director of Advocacy Liz Nelson raises the importance of delivering the ABC’s of tax transparency through the UN tax convention to reclaim national tax sovereignty and bolster democratic processes.

4 Feb 2026 4:06pm GMT – ECOSOC Special Meeting on Financial Integrity underway

There are no negotiation sessions today (resuming tomorrow as normal) but there is a Special Meeting by the Economic and Social Council. You can watch this live on UN Web TV (or below). The full programme for the meeting is available here.

4 Feb 2026 3:17pm GMT – African Union’s response to “renegotiating 3000 treaties“

Here’s a clip from yesterday’s negotiations on the fair allocation of taxing rights (Article 5) featuring a brilliant response from the African Union to the complaint that implementing fair taxing rights would require renegotiating 3000 treaties.

Here’s Tax Justice Network Africa‘s insightful intervention backing this point – and reminding everybody that addressing the historical imbalances between countries is exactly the point of the commitment.

Lastly, in case you missed it, this joint intervention from War on Want and the Global Alliance for Tax Justice is a must-watch.

4 Feb 2026 11:59am GMT – Detailed summaries of negotiations on specific commitments added

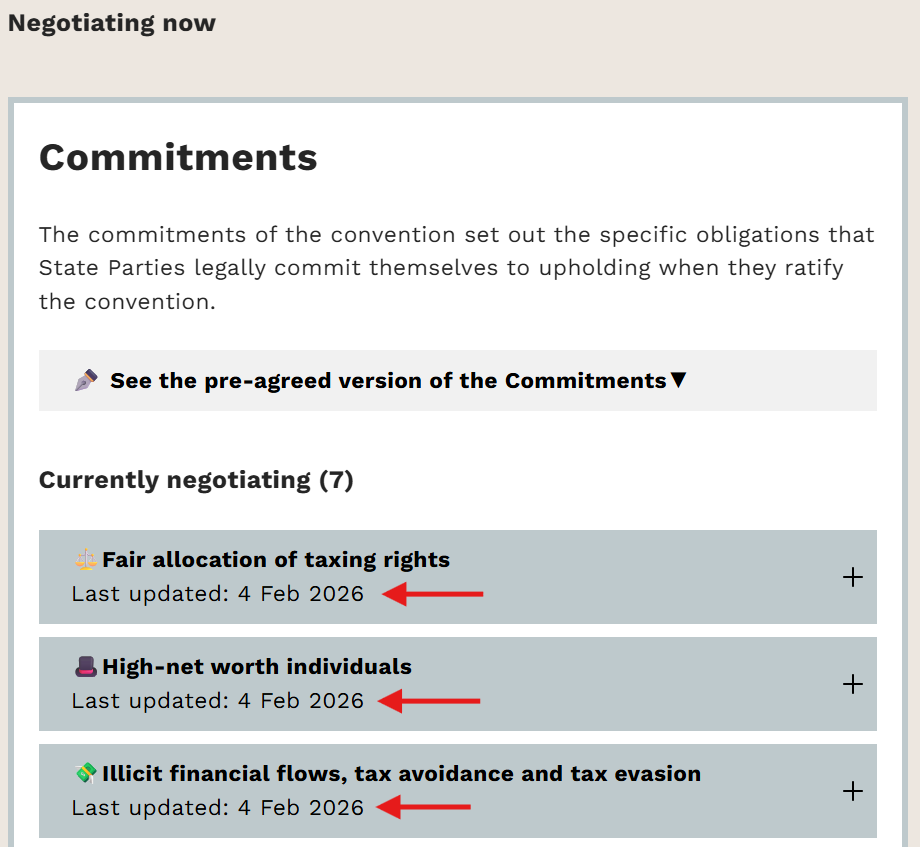

Scroll down to our “Build-a-convention” section below to see our new detailed updates on yesterday’s negotiations on fair allocation of taxing rights (Article 5), high-net-worth individuals (Article 6), and illicit financial flows (Article 7).

3 Feb 2026 3:37pm GMT – Day 2 of negotiations begins

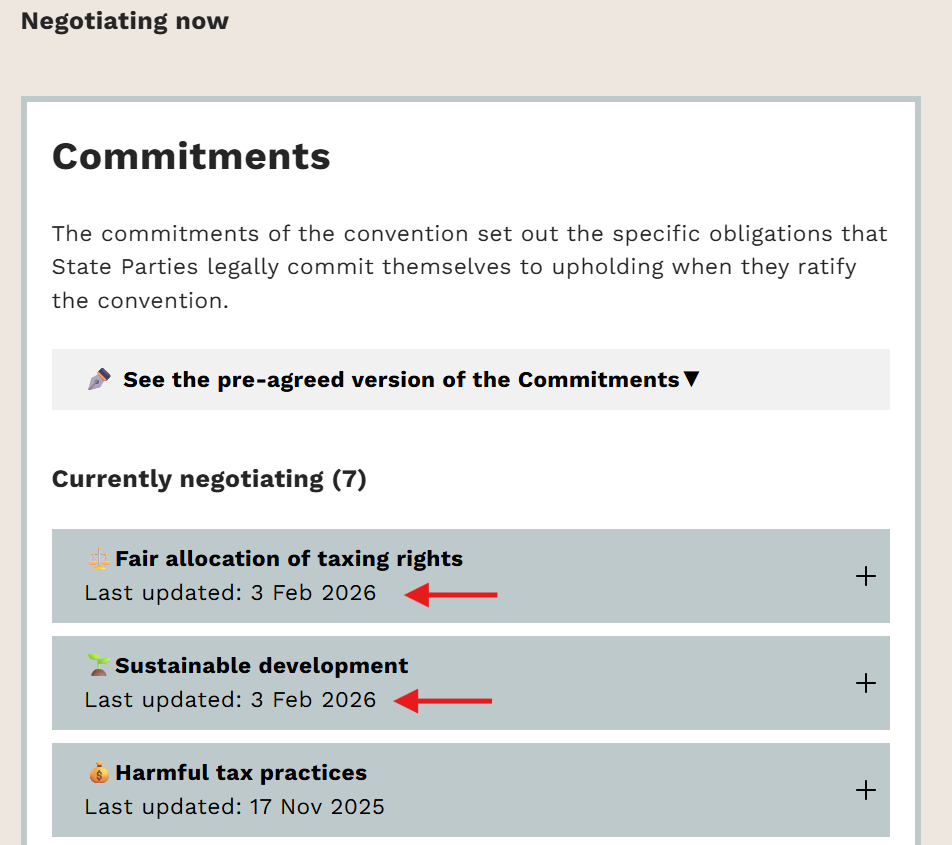

The morning session is underway. You can follow the negotiations live on UN Web TV (or watch it below) and find the full schedule here. On everybody’s mind today is continuing yesterday’s talk on Article 5 (fair allocation of taxing rights). A recap of yesterday’s talk on this article is available further below on this webpage, in the “Build-a-convention” section.

3 Feb 2026 11:55am GMT – Detailed updates on negotiations of commitments to fair allocation of tax rights and to sustainable developments added

Scroll down to our “Build-a-convention” section below to see our new updates on yesterday’s negotiations of these two commitments (Article 4 and Article 5).

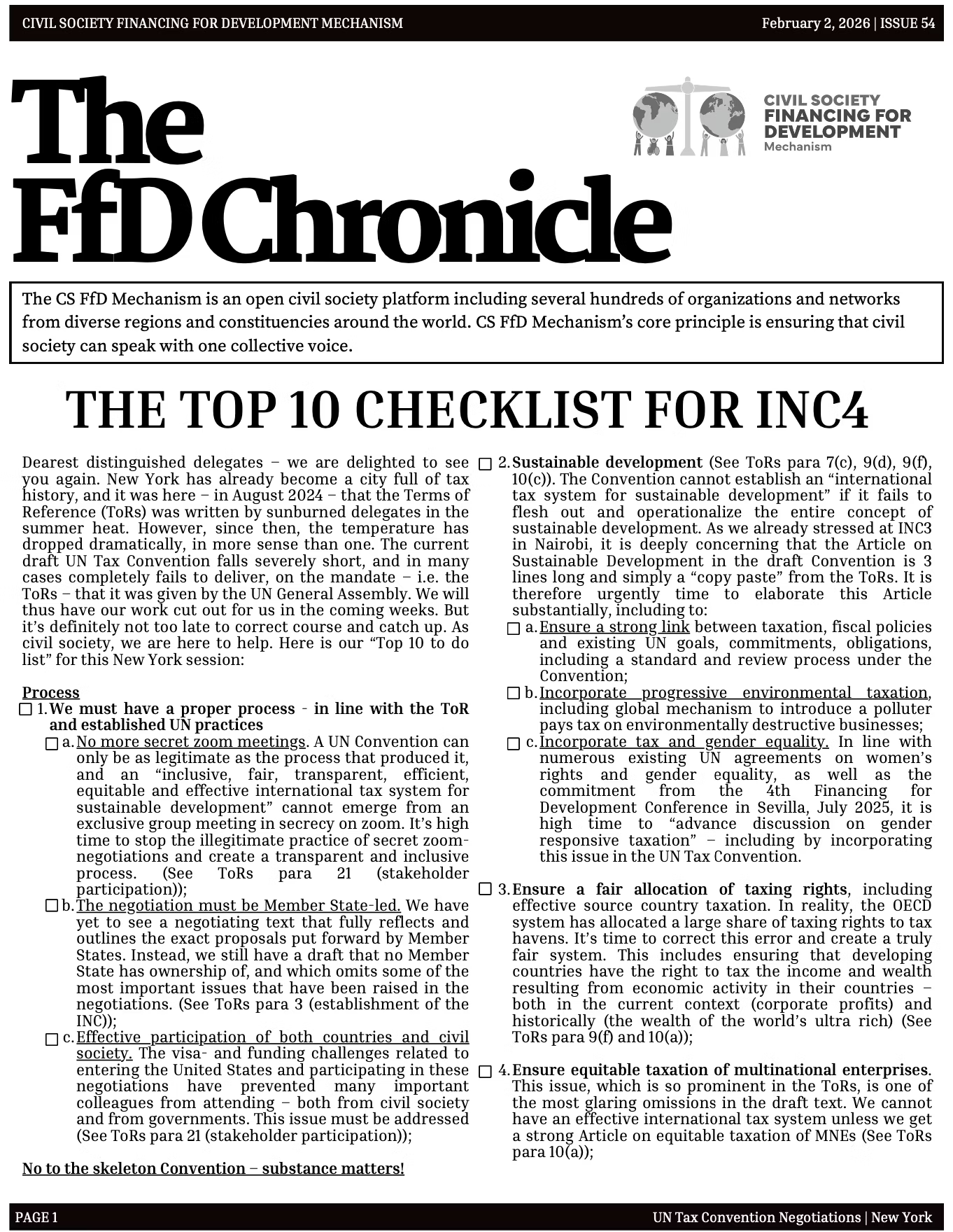

2 Feb 20265 4:38pm GMT – ‘FfD Chronicle’ newsletter publishes “top 10 to-do list” for UN tax talks

The newsletter is published by members of the Civil Society Finance for Development Mechanism who are on the ground at the negotiations, offering invaluable and original insight. It’s only published during active negotiations. Read the latest issue published today here.

2 Feb 4:03pm GMT – “International tax cooperation goes to the heart of national sovereignty” says UN Assistant Secretary-General in opening remarks

Powerful words from Mr. Navid Hanif, the Assistant Secretary-General for Economic Development in the Department of Economic and Social Affairs, to kick off the fourth round of negotiations:

“International tax cooperation goes to the heart of national sovereignty. It affects how states finance development and it touches directly on sensitive policy choices. That is precisely why this process matters. It must reflect the United Nations distinctive approach to multilateralism. Open, inclusive, transparent and grounded in mutual respect. The legitimacy of this convention will depend not only on what we agree but on how we arrive there.”

Watch the statement here.

2 Feb 3:16pm GMT – Fourth Session of negotiations begin

And…we’re off! You can follow the negotiations live here and find the full schedule here. (or do so below)

2 Feb 2026 9:45am GMT – Media coverage ahead today’s talks

Here’s a round up of some articles this morning ahead of the start of the Fourth Session of UN tax convention negotiations in New York today.

- Fossil fuel firms may have to pay for climate damage under proposed UN tax – The Guardian

- La souveraineté fiscale n’est pas une question technique mais un enjeu de pouvoir politique – Le Monde

- UN Fast-Tracks Global Tax Overhaul as OECD Stalls – Envoy

30 Jan 2026 5:30pm GMT – Blog ahead of UN tax convention talks resuming

With the Fourth Session of negotiations on the UN tax convention kicking off next week, our Senior Research Florencia Lorenzo – who will be at the negotiations in New York – has published this blog recapping where the negotiations currently stand and what we can expect over the coming days.

Like before, we’ll be sharing regular updates and analysis on this webpage as the negotiations unfold.

🧩Build-a-Convention tracker

Negotiating global conventions is messy work, so we’ve broken the process down into building blocks to help make it easier to follow.

Below you’ll find the “building blocks” – things like commitments and protocols – that need to go into the UN tax convention’s different sections. You can expand each building block to learn more about it and see the latest updates on its negotiations.

Countries already pre-agreed before the negotiations began on what building blocks should go into the convention and what these should look like. You can see these in the Terms of Reference. We’re working with campaigners around the world to help make sure countries stick to the world-changing terms they committed to.

Negotiating now

Protocols

The protocols of the convention are specific and important obligations that implement the convention’s objectives. Protocols allow these kind of obligations to be negotiated individually, making for an easier and faster negotiation process.

✒️ See the pre-agreed version of the Protocols▼

From the Terms of Reference adopted by the UN:

Protocols

14. Protocols are separate legally binding instruments, under the framework convention, to implement or elaborate the framework convention. Each party to the framework convention should have the option whether or not to become party to a protocol on any substantive tax issues, either at the time they become party to the framework convention or later.

15. Two early protocols should be developed simultaneously with the framework convention. One of the early protocols should address taxation of income derived from the provision of cross-border services in an increasingly digitalized and globalized economy.

16. The subject of the second early protocol should be decided at the organizational session of the intergovernmental negotiating committee and should be drawn from the following specific priority areas:

(a) Taxation of the digitalized economy

(b) Measures against tax-related illicit financial flows

(c) Prevention and resolution of tax disputes

(d) Addressing tax evasion and avoidance by high-net worth individuals and ensuring their effective taxation in relevant Member States

17. Protocols addressing the following topics, inter alia, could be considered:

(a) Tax cooperation on environmental challenges

(b) Exchange of information for tax purposes

(c) Mutual administrative assistance on tax matters

(d) Harmful tax practices

Currently negotiating (2)

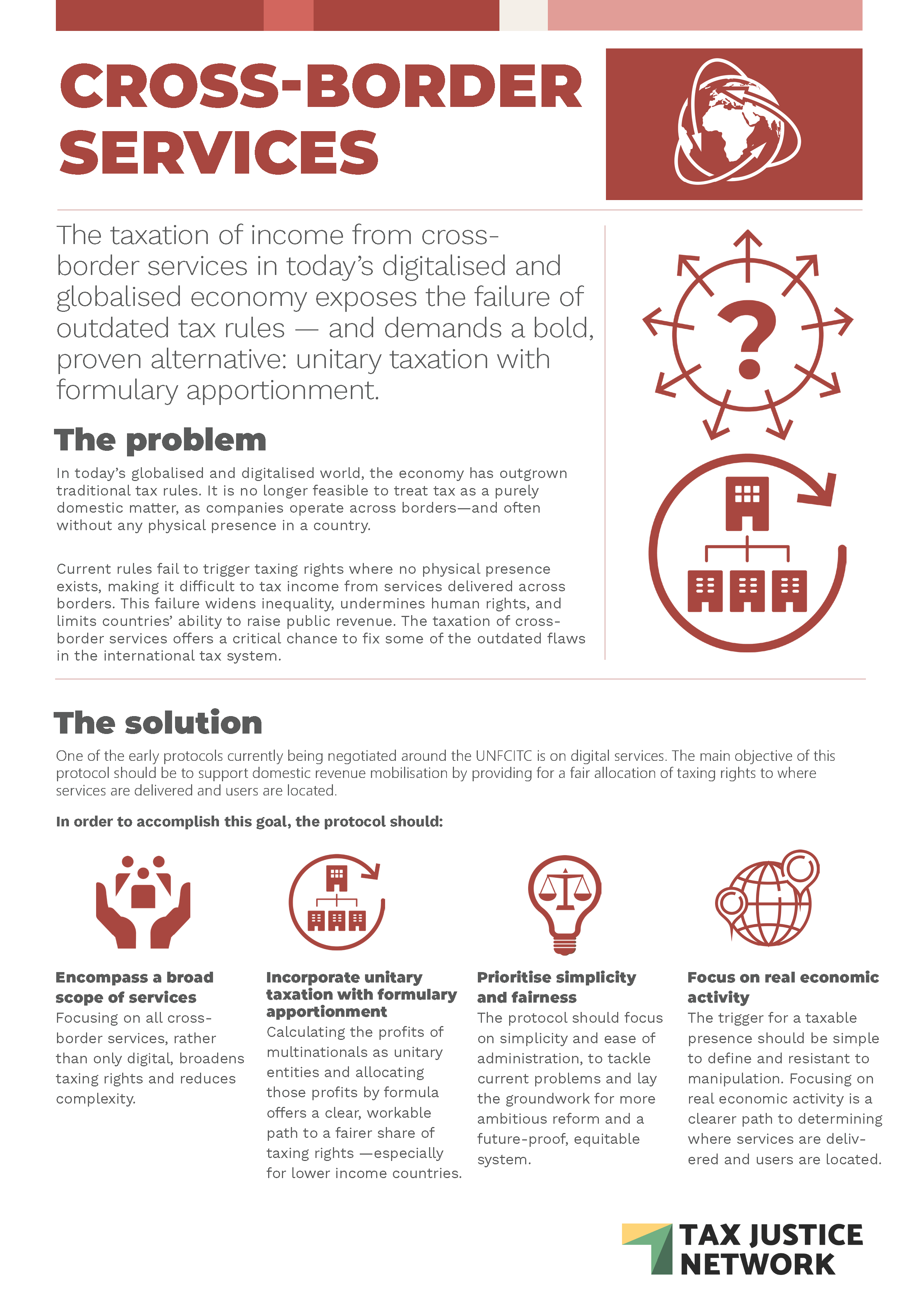

🌍Cross-border services

Last updated: 12 Feb 2026

Explainer🧠

Taxing cross-border services is a key challenge in international tax negotiations. More and more services — from digital platforms to remote consulting — are now provided across borders without the provider ever setting foot in the customer’s country. Without clear and fair rules, this creates uncertainty over which country has the right to tax the income and raises the risk of double taxation or tax abuse. The Protocol offers an opportunity to agree inclusive and effective global rules for taxing different types of cross-border services, especially in an era of digitalisation and remote service provision.

Negotiation updates 🤝

12 Feb 2026: Final day of negotiations on one of the most challenging topics of international tax

Wednesday 11 February 2026 was the third and find consecutive day that delegates focused their attention on Services Protocol. The negotiations covered the remaining element for discussion of the Co-Lead’s Draft Options Paper. This element was the matter of ‘implementation’ of the Protocol.

Implementation

As the Co-Lead explained, many countries have argued in favour of revisions of the current rules on the taxation of cross-border services because the current rules are marred with imbalances between countries. The current rules are contained in the existing bilateral tax treaties. The Protocol provides countries with the opportunity to devise a multilateral process to allow more rapid implementation of changes than through bilateral negotiations.

The question submitted to the delegates was whether the Protocol should remain silent on the interface with bilateral tax treaties and thus leave implementation to bilateral negotiations, or whether its rules should be granted priority in case of a conflict of norms. An intermediary solution may be the adoption of matching system similar to the OECD Multilateral Instrument on BEPS (MLI). Under the MLI, countries assign those bilateral tax treaties they want to see changed by the new rules and these new rules are then imposed as an overlay on ‘covered’ bilateral tax treaties if both treaty partners have listed the treaty and there is a match. The UN Tax Committee has recently developed a proposal for a similar instrument, known as the Fast-Track Instrument (FTI) which operates in similar fashion as the MLI but imposes change through the addition of standardized amending protocols to existing bilateral tax treaties.

Country opinions were divided. India believed the first option is to be preferred. The MLI option only makes sense if countries have roughly equal amount of tax treaties in place, which is not the case. Some countries have over 120 bilateral tax treaties in place, other countries present have only a handful of treaties or less. An MLI ‘matching system’ does not help these countries. Nigeria and Israel added that previous experience revealed that MLI type solutions are incredibly complex and difficult to understand, including for the taxpayer. Norway agreed, noting that the UN Tax Committee’s FTI proposal is equally complex. The Co-Lead brought some nuance by noting that the MLI experience across countries seemed to be mixed, as there were also countries that had found the mechanism to be without problems.

Saudi Arabia, in contrast to India, noted that the first option of doing nothing and leaving change to bilateral negotiations would likely not deliver meaningful results. On the other hand, an automatic override of all relevant bilateral treaty provisions may also raise concerns. The MLI approach therefore seemed to be the least problematic way forward.

Kenya and Ghana, in turn, refused to accept a dismissal of the automatic override option. Kenya was adamant that the Protocol should supersede relevant existing bilateral tax treaty rules. Legally speaking, such an approach would be in line with the principles of customary international law, as enshrined in article 33 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties.

While automatic override may very well be legally sound, Switzerland’s subsequent response showed that its adoption as a solution in the Protocol largely depends on countries’ political will to achieve change. In the Swiss delegate’s view, an automatic override by the Protocol would drastically reduce the number of countries that would sign on to the Protocol as an automatic override would risk upsetting the ‘balance’ of bilateral tax treaty which was carefully crafted through bilateral negotiations. Countries should at least be allowed to assign which treaties they want to see changed, and that can only be achieved through an MLI like approach. China, too, noted that a bilateral tax treaty reflects a balance of concessions which is unique and delicate and which is based on individual bilateral relationships. China believed that flexibility in the implementation methods was therefore a must. Canada and France also expressed unwillingness to automatically let go of what they see as ‘balanced’ tax treaties for the sake of a what many other countries see as a fair allocation of taxing rights. Sierra Leone, for example, noted that there is nothing ‘balanced’ about tax treaties with developing countries that have negotiated in situations of asymmetric bargaining power. Sierra Leone added that a hybrid implementation approach whereby the Protocol establishes clear rules of precedence in case of conflicts with tax treaties while allowing narrowly defined reservations and transitional arrangements may be an option to consider. Any implementation mechanism must recognize the limited administrative and negotiating capacity of many developing countries. Zambia agreed and expressed its disagreement with implementation approaches that would involve bilateral (re)negotiation as these negotiations would risk to undermine coherence and consistency of implementation. A automatic override of both domestic and tax treaty law is the only meaningful way forward. Brazil concurred with this point: even for a large country like Brazil obtaining source taxation of cross-border services income is difficult and often comes at a high cost. A multilateral negotiation and implementation is needed to change these negotiation dynamics. Also, if more countries accept these new rules and a new level playing field is created, countries may be more willing to accept the new rules.

A final issue that left delegates with many question with was the implementation of the Protocol in situations where there is no tax treaty in force. Belgium, for example, expressed doubt on how the Protocol could play a role in no-treaty situations. Ghana responded by noting that the point of the Protocol is to create a multilateral instrument that covers all countries, and not just those with tax treaties. Whether country has many or few tax treaties should not matter. In line with the spirit of inclusiveness that carries the whole of the Framework Convention itself, the Protocol should cater to the needs of all countries.

With this final debate, three intensive days of intense negotiations on one of the most challenging topics of current international tax policy came to an end. Progress may seem slow and difficult, but then again, it took the OECD ten years to fail the exact same challenge. The UN process is therefore due some more time before judgement day comes.

12 Feb 2026: Second day of negotiations on Protocol 1 focus on nexus and method of taxation

The negotiations continued on Tuesday 10 February with the discussions of Protocol 1 on cross-border services, and more specifically on the nexus between country and taxable income from services.

India was keen to build on the yesterday’s consensus among countries that different type of service may require different nexus rules and provided a classification of services in four classes. A first class of services occurs with physical presence of the service provider, like the case of construction, installation or maintenance activities. The second class of services are services that are delivered remotely but in the country from which they are delivered there is a strong human intervention. Software development by an entity residing in India and providing services to an overseas affiliate is a clear example. Often, these services transactions will be subject to transfer pricing rules. The third class of services are those remote services that require no or very little human intervention, like streaming services, cloud computing, online advertising and so on. These are heavily automated services. The fourth class of services are the services provided by digital platforms, like ride hailing services and other gig economy platforms. The Indian delegate added that differentiation of services can also be made as to whether they are B2C or B2B services and in function of the general level of profitability or in function value creation, whether market facing or not.

Switzerland added that it mainly saw two different types of services: those that involve physical presence and those that do not involve physical presence. Scalability of business models may also be a factor to consider, as scalability often goes hand in hand with high profitability and thus with more justification for shared taxing rights.

Kenya took the debate a step further applying the different nexus options to the categories of services proposed by the Indian delegate. Three nexus options had been identified in yesterday’s discussions: payment or remittance, market engagement and physical presence. The Kenyan delegate noted that the first class of services – services which entail physical presence – the physical presence nexus should be sufficient. However, the current permanent establishment threshold may not be adequate and reduced temporal thresholds for presence may be necessary. For the second class of remote services with human involvement, a mix of nexus may be needed because both payor and user/recipient of the service may be relevant. For automated digital services and platform services too both payor and user nexus are relevant.

Other countries were not so convinced with the Indian and Kenyan view on categories and relevant nexus. Italy, for example, hammered on the relevance of capital and intangible location as an important nexus, although the Italian delegate did admit that in some business models, users are an important value driver. Norway shared some of the Italian criticism by noting that more analysis is needed of different service business models before making decisions on appropriate nexus rules. France relied on examples of international transport services and remote services by an architect to support its claim that lower thresholds on the physical presence nexus are difficult to conceive.

Countries agreed they would revisit the complex topic of nexus rules in a later stage of the negotiations.

Method of taxation

Next, country delegates discussed the appropriate method of taxation for income from services with nexus to a particular country. Possible methods range from a withholding tax on gross payments for services to taxation of net income from services, which implies deduction of expenses and offsetting of previous losses.

Nigeria noted that gross taxation by withholding fits well with the payor nexus. It may not be suitable for other types of nexus, though. France believed that even when gross taxation by withholding is a suitable method, like in the case of payor nexus, taxpayers should be entitled to net taxation. The Co-Lead chimed in on this by noting that the UN Model provides rules on services by which net taxation in line with the permanent establishment threshold and gross taxation on service fee payments work in parallel as alternatives. The Co-Lead also noted that net taxation may be more fair and equitable because it allows expense deduction and loss offsetting but it comes with a higher administrative burden.

Canada, Switzerland and Italy referred to a recent consultancy paper by the business interest lobby that makes the claim that withholding taxes on services, on aggregate, have a negative economic effect on countries and their foreign investment numbers. The Co-Chair was not so convinced by these findings in light of her own country experience and noted that individual countries have individual situations to deal with, making aggregate findings less relevant. Singapore agreed gross taxation may impede cross-border trade and investment and believed net taxation was the only fair method as gross taxation risks leading to over-taxation, thereby breaching the ability to pay principle.

The Co-Lead noted that some of the countries that rejected the prospect of gross taxation by withholding where also countries that have implemented digital services taxes (DSTs), which, economically speaking, have the same effect as gross taxation if not worse. She wondered about the economic impact of those taxes. The Canadian delegated avoided the question by noting the crux of the matter is the provision of an optional mechanism for net taxation so taxpayers can elect the method that fits best with their business. On the issue of optionality, Austria noted that its DST is a tax on gross without the option for net taxation. On the other hand, under Austrian income tax, there are situations in which non-residents are forced to declare taxes and are assessed on net basis.

The Co-Lead closed the meeting by noting that tomorrow’s negotiations will cover the final sub-topic of implementation while also revisit the nexus topic.

Belgium advocated for an express exemption of the international transport industry from the new protocol, ignoring the previous consensus that the purpose of the protocol is to cover all services.

The second week of negotiations kicked off with the heavily anticipated discussions on Protocol 1 on ‘Taxation of income derived from the provision of cross-border services in an increasingly digitalized and globalized economy’. The Co-Lead of Workstream 2, Liselott Kana, presented the Co-Lead’s Draft Options Paper. This recent discussion paper provides for possible directions for the protocol to take with regard to scope of taxes covered, nexus rules employed, method of taxation (gross or net) and questions of implementation, especially regarding the interface between the protocol and existing tax treaties. The Co-Lead emphasized the need to move from options to solutions.

Scope of taxes covered

With regard to the first subtopic of the day, the scope of the protocol, solutions were not easily found. The Co-Lead’s paper proposed for the protocol to cover taxes on income and other taxes with the same economic effect but without going into strict categorization of taxes covered and not covered. As explained by the Co-Lead, the purpose is to take a comprehensive approach to the taxation of income or revenue from cross-border services which, as the current country practice of DSTs shows, is not limited to income taxes in the strict sense. Countries should avoid the current situation where one treaty partner believes a tax on services is not covered by their tax treaty because it is strictly speaking not an income tax whereas its treaty partner believe the tax is covered because it is an income tax by any other name.

Countries like Nigeria, India and and Ghana agreed this approach was sensible. Other countries were not as convinced. The United Kingdom, for example, believed the purpose of the protocol was to review certain limits imposed by existing tax treaties and tax treaties only cover income taxes so dealing with non-income taxes seemed a bridge too far. Estonia and Germany urged caution regarding the possible coverage of VAT. Germany believed the protocol should not necessarily be restricted to income taxes. However, clear criteria are needed to define what type of quasi-income taxes are covered to avoid a blanket clause which covers all kinds of taxes. The Co-Lead responded the protocol was not intended to cover a genuine VAT but the coverage of VAT charge engineered to have a similar effect as an income tax should not be excluded. Kenya and Ghana agreed, with the latter noting that a VAT is a tax on consumers, not on service providers and thus fundamentally out of scope.

Canada, Belgium and Italy would not want to commit to a wide scope for the protocol without first establishing the nexus rules for the taxation of income from services. These countries would only want to discuss scope after discussing nexus rules. The Co-Lead rebuked this suggestion as in her view, the purpose of the work is to come with a comprehensive solution for the taxation of services. This cannot be achieved if the discussion on scope is determined by the outcome of the discussion on nexus.

Nigeria strongly agreed with the Co-Lead’s view: tax laws and tax treaties starts by defining the scope of what is covered. This should not be different in the case of this protocol.

To avoid the discussions falling into a semantic rabbit hole, the Co-Lead move the conversation on to the next sub-topic, which is the scope of services covered.

Scope of services covered

On this topic, there was more consensus among delegates. Countries generally agreed that the protocol should have a broad scope and cover all services. An additional question, however, is whether the protocol should differentiate between different kind of services for the sake of applying different nexus rules or rates.

The African Group noted that it was not adverse to the idea of structured classification and categorization of different kind of services but it would need to see the proposed categorization to determine whether it would be acceptable or not. India, drawing from its experience governing a vast services economy, noted that differentiating is simply unavoidable. Switzerland agreed, especially if gross taxation would be contemplated as a solution, given that different services come with different profit margins.

Canada noted that studies like the recent ICC study on the impact of Article 12AA of the UN Model seemed to show that the taxation of certain types of services may not be beneficial, making differentiation relevant. Norway agreed that any solution contemplated should effectively deliver on domestic resource mobilization.

The Co-Lead responded rather than focusing on treaties with or without 12AA, a often ignored fact is that many countries simply opt not to conclude tax treaties at all because they think the model rules are not in their national interests. The protocol should also appeal to those countries. The Belgian delegate expressed disbelief regarding certain countries’ negative attitude towards the models and emphasized that everybody knows (sic.) that tax treaties are important to attract foreign investment. The Co-Lead responded that the group of countries that does not engage in the signing of tax treaties is big and this fact should not be downplayed.

12 Feb 2026: First day of negotiations on Protocol 1 proves tense

The second week of negotiations of the Fourth Session kicked off on Monday 9 February 2026 with the heavily anticipated discussions on Protocol 1 on ‘Taxation of income derived from the provision of cross-border services in an increasingly digitalized and globalized economy’. The Co-Lead of Workstream 2, Liselott Kana, presented the Co-Lead’s Draft Options Paper. This recent discussion paper provides for possible directions for the protocol to take with regard to scope of taxes covered, nexus rules employed, method of taxation (gross or net) and questions of implementation, especially regarding the interface between the protocol and existing tax treaties. The Co-Lead emphasized the need to move from options to solutions.

Scope of taxes covered

With regard to the first subtopic of the day, the scope of the protocol, solutions were not easily found. The Co-Lead’s paper proposed for the protocol to cover taxes on income and other taxes with the same economic effect but without going into strict categorization of taxes covered and not covered. As explained by the Co-Lead, the purpose is to take a comprehensive approach to the taxation of income or revenue from cross-border services which, as the current country practice of DSTs shows, is not limited to income taxes in the strict sense. Countries should avoid the current situation where one treaty partner believes a tax on services is not covered by their tax treaty because it is strictly speaking not an income tax whereas its treaty partner believe the tax is covered because it is an income tax by any other name.

Countries like Nigeria, India and and Ghana agreed this approach was sensible. Other countries were not as convinced. The United Kingdom, for example, believed the purpose of the protocol was to review certain limits imposed by existing tax treaties and tax treaties only cover income taxes so dealing with non-income taxes seemed a bridge too far. Estonia and Germany urged caution regarding the possible coverage of VAT. Germany believed the protocol should not necessarily be restricted to income taxes. However, clear criteria are needed to define what type of quasi-income taxes are covered to avoid a blanket clause which covers all kinds of taxes. The Co-Lead responded the protocol was not intended to cover a genuine VAT but the coverage of VAT charge engineered to have a similar effect as an income tax should not be excluded. Kenya and Ghana agreed, with the latter noting that a VAT is a tax on consumers, not on service providers and thus fundamentally out of scope.

Canada, Belgium and Italy would not want to commit to a wide scope for the protocol without first establishing the nexus rules for the taxation of income from services. These countries would only want to discuss scope after discussing nexus rules. The Co-Lead rebuked this suggestion as in her view, the purpose of the work is to come with a comprehensive solution for the taxation of services. This cannot be achieved if the discussion on scope is determined by the outcome of the discussion on nexus.

Nigeria strongly agreed with the Co-Lead’s view: tax laws and tax treaties starts by defining the scope of what is covered. This should not be different in the case of this protocol.

To avoid the discussions falling into a semantic rabbit hole, the Co-Lead move the conversation on to the next sub-topic, which is the scope of services covered.

Scope of services covered

On this topic, there was more consensus among delegates. Countries generally agreed that the protocol should have a broad scope and cover all services. An additional question, however, is whether the protocol should differentiate between different kind of services for the sake of applying different nexus rules or rates.

The African Group noted that it was not adverse to the idea of structured classification and categorization of different kind of services but it would need to see the proposed categorization to determine whether it would be acceptable or not. India, drawing from its experience governing a vast services economy, noted that differentiating is simply unavoidable. Switzerland agreed, especially if gross taxation would be contemplated as a solution, given that different services come with different profit margins.

Canada noted that studies like the recent ICC study on the impact of Article 12AA of the UN Model seemed to show that the taxation of certain types of services may not be beneficial, making differentiation relevant. Norway agreed that any solution contemplated should effectively deliver on domestic resource mobilization.

The Co-Lead responded rather than focusing on treaties with or without 12AA, an often ignored fact is that many countries simply opt not to conclude tax treaties at all because they think the model rules are not in their national interests. The protocol should also appeal to those countries. The Belgian delegate expressed disbelief regarding certain countries’ negative attitude towards the models and emphasized that everybody knows (sic.) that tax treaties are important to attract foreign investment. The Co-Lead responded that the group of countries that does not engage in the signing of tax treaties is big and this fact should not be downplayed.

Nexus

Next, the discussions moved on to the topic of ‘nexus’, namely the question regarding the parameters of connection between country and income from services that determine whether the country can tax such income. The Co-Lead asked delegates for views on the payment nexus, the physical-presence nexus and the economic/market nexus.

The African Group strongly supported a protocol that covers all services with different nexus rules for different categories of services. Services rendered physically should follow the physical presence nexus. Automated digital services require a new types of nexus, such as user location. Italy believed however that the consumer itself does not contribute to economic value creation. Only when the consumer or user contributes to value creation by providing data, granting nexus is appropriate.

Kenya disagreed with the Italian point. Current nexus rules are heavily skewed towards supply based factors. Value creation is also provided by demand based factors, and these are the consumers. India believed the concept of value creation is a complicated one, as it means different things in different business circumstances: is value created by Indian engineers developing software or by offshore superiors signing off the engineers’ decision or managing the business.

With regard to physical presence, countries like the United Kingdom, Italy, Japan and Canada hammered on the continued relevance of the permanent establishment rule and cautioned against undue changes to this fundamental nexus concept. This led to the Co-Lead cautioning those states not gloss over the fact that countries across the room have varied views on what conceives a PE. Kenya added that the current physical presence PE concept is also not without problems: setting up a very temporary event that generates billions of revenue clearly involves physical presence but will most likely not trigger PE status. Zambia added that the current physical presence PE concept is based on thresholds which give rise to tremendous avoidance behavior through fragmentation of activities and structuring. Rather, it would be better to focus the nexus on economic participation in the market.

Saudi Arabia agreed the physical presence nexus is relevant for traditional services that cannot be delivered remotely. For remote services, the traditional permanent establishment thresholds no longer capture a meaningful economic participation. For those services, shorter duration thresholds are required and it may be needed to consider different types of nexus in line with the types of service at hand. For online advertisement services, for example, the relevant link may be the location of the viewers of the advertisement.

Saudi Arabia also raised the important question of the interplay of various nexus rules, wondering whether the protocol envisages a type of hierarchy of nexus rules or parallel operation of nexus rules, granting taxing rights to various ‘source countries’ on the same income from services. The Chines delegate chimed in on this point, noting that agreeing on various nexus claims in a bilateral context is often challenging. This made him wonder how the conflict of overlapping nexus claims can be solved in a multilateral setting where there are many more stakeholders and countries involved and which will all demand to be taken into consideration.

Jamaica agreed that there may be different nexus rules for different types of services but wondered whether, in the context of (the draft) Article 5 of the Framework Convention, there was a need to determine which elements of the possible nexus would constitute a fair allocation of taxing rights. If different nexus rules could potentially apply, the one that grants a fair allocation should prevail.

All in all, it was a tense first day of negotiations on Protocol 1. As Muhammed Ali once said: “It isn’t the mountains ahead that wear you out, it’s the pebble in your shoe”. As the first day of negotiations showed, lot’s of pebbles in the Co-Lead and the delegates’ shoes to be dealt with on the road to success in this protocol.

Previous updates (3)

15 Aug 2025: Second round of negotiations kicked off with scoping discussion on early protocol on cross-border services

Between Monday and Wednesday of the second round of negotiations, discussions on the early protocol for taxing cross-border services focused on the technical and political challenges of designing rules that are fair, feasible and adaptable across regions.

Delegations debated whether the protocol should be self-executing or require additional legal instruments. Some participants highlighted the need for clear and uniform withholding tax rates to provide certainty and limit opportunities for tax abuse, while others cautioned against rigid approaches that might reduce flexibility.

A major theme was the balance between simplicity and precision. Fixed, low withholding rates were seen by some as a way to ensure predictability and avoid double taxation. Others argued that service transactions vary too widely for a one-size-fits-all solution.

The debate also reflected North–South differences. Developing countries underlined the importance of predictable source-based taxation to protect their revenue base, while several developed countries emphasised administrative feasibility, alignment with existing OECD treaty practice, and safeguards against over-taxation.

Delegations also discussed the scope of covered taxes, which stemmed from differing characterisations of certain digital service taxes under national legislation. Questions were raised about whether the protocol could be ratified independently of the convention and how disputes arising from its application might be resolved.

Overall, the first three days revealed convergence on the urgency of establishing clearer global rules for cross-border services, but divergence on the appropriate design of withholding taxes and the legal framework required to implement them.

21 July 2025 Member states’ written submissions on Workstream II co-leads’ draft issue note

Country submissions on the protocol for taxing cross-border services revealed sharp divisions between regions. Many developing countries, including the Africa Group, Brazil and others, rejected outdated physical presence rules and supported broader nexus definitions such as significant economic presence. They strongly favoured gross-basis withholding taxes as a simple and effective tool to secure source taxing rights, especially in contexts with limited administrative capacity. Many also saw these as a proxy for net taxation and a way to protect fiscal space.

By contrast, many developed countries emphasised physical presence, defended net taxation as economically efficient and consistent with OECD treaty practice, and cautioned that withholding could unfairly shift taxing rights towards source states.

Divergences also extended to the scope of services and the relationship with tax treaties. Global South countries pressed for broad coverage of digital and emerging services, as well as multilateral solutions to overcome restrictive treaties. Many Northern countries preferred a narrower scope aligned with existing OECD standards and defended the legitimacy of the bilateral treaty network.

27 June 2025 Draft issue note published by Workstream II co-lead (Chile)

A draft issue note has been published by the co-lead of Workstream II.

Key issues identified include differences among domestic laws on whether to tax services on a gross basis (withholding) regardless of where services are performed, or on a net basis linked to physical presence or permanent establishment.

The protocol will consider new nexus rules, such as significant economic presence and user participation, to ensure that source jurisdictions can exercise taxing rights even when services are provided remotely.

It will also define which types of services are in scope — for example, intra-group technical or managerial services, remote services and automated digital services — and which categories of taxes apply, including income and withholding taxes. Deliberations will address how to treat digital services taxes and whether to classify coverage by the name of a tax or by its nature.

Principles to guide the design are also under discussion: fairness, administrability, simplicity, neutrality and future-proofing, so that the rules remain relevant as business models evolve.

Analysis💡

Tax Justice Network’s analysis – 14 Oct 2025

From the Tax Justice Network’s perspective, negotiations on the protocol for taxing cross-border services made important headway by placing the need for predictable global rules for all types of services at the centre of the debate. However, they also revealed how far consensus remains.

Developing countries called for clear, low, gross-basis rates to protect source taxation and secure much-needed revenue. Many developed countries, by contrast, favoured net taxation and greater flexibility to maintain consistency with existing OECD treaty practice.

This divide reflects deeper structural imbalances in international tax rules — rules that have long deprived source countries of the ability to tax services and often failed to ensure that the countries where services are performed receive a fair share of tax revenue.

As the Tax Justice Network stressed in its submission, the protocol should not be limited to narrow fixes. It must lay the foundation for a multilateral system that replaces outdated nexus rules and complex transfer pricing with approaches that treat multinational companies as unitary entities and allocate profits according to real economic activity.

To make this possible, the protocol should retain a broad scope that captures all relevant services and introduce new nexus rules that move beyond the outdated requirement of physical presence. There is also a need to rebalance taxing rights towards source and market jurisdictions.

The ultimate test will be whether the protocol creates a future-proof system that prevents treaty shopping, secures taxing rights for the Global South, and supports domestic resource mobilisation for sustainable development.

❤️Dispute prevention and resolution

Last updated: 26 Nov 2025

Explainer🧠

Disputes over how much tax is owed and where it should be paid are common in cross-border bussiness, and when countries cannot resolve them efficiently, it creates uncertainty for governments and companies alike. This protocol represents a key opportunity to design universal mechanisms for preventing and resolving tax disputes in line with the principles set out in the Framework Convention.

By finding common ground on the rules for preventing and resolving tax disputes, the protocol can play a critical role in fulfilling the objectives of the Framework Convention, including the mobilisation of resources for sustainable development and the fulfilment of human rights

Negotiation updates 🤝

26 Nov 2025: Summary of three days of negotiations in Nairobi on the dispute protocol

Over the last three days of the Third Session, the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee discussed the progress made in Workstream 3 on the protocol on the prevention and resolution of tax disputes. The discussions, led by the Co-Leads from Jamaica and Germany, centered on the questions raised in the Co-Leads’ Concept Note on Ideas for Potential Solutions of 24 October 2025.

Optionality

In the previous meeting, it had already been clear that countries were open to the idea of making some of the various rules that would be developed under the protocol optional. During the current session, there was broad support for the Co-Leads’ proposed two-step approach on optionality: first, elaborating a comprehensive menu of mechanisms for prevention and resolution, and then, subsequently identifying core mechanisms that should be available to all parties. Delegates emphasized that optionality is an essential feature to ensure maximum participation, inclusion, and adoption of the protocol by countries with diverse administrative capacities.

As to the content of the ‘core mechanisms’, countries like India and Kenya (speaking on behalf of the African Group) emphasized that the core mechanisms should be simple, low-cost, easy to implement, and should not impose undue administrative burdens on resource-constrained jurisdictions. The Mutual Agreement Procedure (MAP) or MAP-like solutions were frequently suggested as the appropriate foundation for the core baseline. There was strong caution, particularly from developing countries and the African Union, against classifying mandatory binding arbitration or other resource-intensive procedures as core. Italy also stressed the importance of including the prevention side of the issue within the core mechanisms.

Superseding effect

On the issue of the legal effect of the protocol on existing instruments like bilateral tax treaties, OECD countries stressed that effect over existing and proven effective provisions, unless the concerned parties agree otherwise. They argued that the protocol should primarily address gaps in the current system or provide improvements where existing mechanisms fall short. These countries also believed opt-in/opt-out declarations similar to the BEPS MLI would create both legal certainty and allow most flexibility for countries to generally subscribe to the protocol. Japan and Ireland believed case-by-case opt-ins would not be desirable from a certain perspective.

Scope of the protocol

Regarding the scope of the protocol, there was broad support for the protocol to focus exclusively on cross-border tax disputes and not on domestic disputes. In their Concept Note, the Co-Leads had suggested the possibility to empower the conference of parties (CoP) to develop and recommend optional future guidance and best practices in relation to domestic dispute resolution in a later state. Countries then zeroed in on the definition of a cross-border tax dispute and the parties involved in such a dispute: tax authorities of two countries, or taxpayer and tax authorities of one or two countries. The Co-Leads had suggested that disputes can be defined as situations with two or more national tax law frameworks asserting taxing rights over the same taxpayer and their transactions or income, which then results in double taxation, even if merely theoretical.

Non-treaty situations

Many countries, like Singapore, Israel and Poland emphasized that for a matter to constitute a formal dispute between countries, there must however be a shared underlying legal basis, such as a tax treaty in place which defines the rights and obligations that give rise to the dispute. The Co-Leads then noted that such a definition of cross-border disputes would essentially rule out any work on a dispute resolution in situations where there is no treaty in place between countries, which would be contrary to the original intent to create mechanisms that are inclusive and accessible to all countries, including those without tax treaties in place. Countries like Singapore and Italy showed their support in exploring how the protocol itself could provide the legal basis, without giving more detail on the nature of this legal basis. The African Union and ATAF subsequently spoke out against work on mechanisms that can be applied to disputes resulting in non-treaty situations. Finally, the Co-Lead from Jamaica reminded the delegates that what the protocol is aiming to do is to improve where possible the current situation where there is a legal basis at hand, such as a treaty, and also where there is no legal basis and countries have to resort to their domestic laws in order to resolve cross-border tax disputes. She also reminded delegates that these countries may not be the one speaking, as they may not be present in the room, but they have to be given consideration as well because the Convention negotiations are supposed to be an inclusive process.

Dispute prevention

Previously, countries had already established that preventing disputes is as important as resolving them. The Concept Note proposed that the protocol could provide a legal basis for dispute prevention mechanisms like (bilateral or multilateral) Advance Pricing Agreements (APAs), joint audits and simultaneous examinations. Many countries supported this approach. Global South countries like Zambia and Bangladesh emphasized the need for capacity building to utilize these complex tools effectively.

Civil society generally agreed with the importance of dispute prevention, but their various interventions stressed that true prevention of disputes requires fundamental changes to the underlying tax rules that give rise to the disputes. As such, they advocated for a shift away from the arm’s length principle toward unitary taxation and formulary apportionment to eliminate the root causes of transfer pricing disputes. CSOs also emphasized transparency measures, such as public country-by-country reporting, as essential prevention tools.

Dispute resolution

– Mutual Agreement Procedure (MAP)

Countries generally supported the idea of establishing the Mutual Agreement Procedure (MAP) as the “core mechanism” of the protocol. The African Group and countries like India stressed that MAP must be made more accessible, efficient, and effective. Suggestions for improvement included setting clear timelines, enhancing transparency, and providing capacity building for developing nations.

– MAP arbitration

On MAP arbitration, the opinions were much more divided. The African Group, India, ATAF and various civil society organizations strongly opposed mandatory binding arbitration, even if the arbitration mechanism would be merely optional. They cited concerns regarding loss of national sovereignty, high costs, lack of transparency, and a historical bias in arbitration outcomes favoring developed nations and multinational enterprises. Nigeria, speaking for the African Group, stated they had their “hands severely burnt” by other forms of arbitrations and viewed the mechanism as skewed against developing countries. Civil Society echoed this opposition to arbitration, describing it as a system that creates “secret courts” and prioritizes corporate interests over public revenue.

Countries like the United Kingdom, Switzerland and Germany advocated nevertheless for MAP arbitration to remain an option within the protocol. They noted that MAP arbitration is not a standalone mechanism but a necessary complement to put pressure on competent authorities to reach a conclusion in the preceding MAP phase. They suggested that the UN could play a role in creating a fairer system, potentially by establishing a pool of neutral arbitrators to address bias concerns.

– Other mechanisms

There was interest in exploring alternative non-binding dispute resolution methods, such as mediation and conciliation. Bangladesh and Japan supported including these as optional tools. India, on the other end of the spectrum, reiterated its position that not only arbitration but any forms of mediation or conciliation should not be employed in the resolution of cross-border tax disputes. The South Centre added that mediation and conciliation are largely untested as tools for tax dispute resolution and may therefore create uncertainty.

Access to Information

– Transfer pricing database

One of the final major topics addressed was the information asymmetry in transfer pricing, specifically the lack of access to data on relevant comparable transactions (‘comparables’) in developing countries. Such data is needed to undertake a comparability analysis to benchmark pricing controlled transactions in transfer pricing assessments. Two primary solutions were debated: creating a public UN-managed transfer pricing database or establishing a pooled purchasing mechanism for commercial databases.

Countries like Bangladesh and Zambia supported a UN-managed database to ensure equitable access for all countries. Zambia noted that commercial databases often lack data relevant to African economic realities, and a UN solution could help address this gap. Several delegations, including Italy, China, and Singapore, raised concerns about the feasibility, high cost, and maintenance burden of a UN database. They suggested that pooled purchasing of existing commercial databases might be a more practical and cost-effective immediate solution. Confidentiality of company data in a UN database was also a concern.

– APA and MAP database

Over the course of the discussions on the protocol and also on the commitment on effective dispute resolution and prevention, certain countries did emphasize the need for more transparency in current dispute resolution processes like APA and MAP. Such transparency can to some extent be achieved by the creation of a database that compiles bilateral APAs and MAP cases. Russia provided a detailed outlook of how such a database could look like. Short summaries of MAP decisions could be included and ongoing MAP cases could be monitored. The OECD currently publishes aggregated MAP statistics, but the database could go beyond that by compiling summaries which could then be analyzed to identify systemic patterns of problems with certain model convention provisions. This would then provide an indication where the existing rules need to be fine-tuned. Russia also suggested that a staggered approach may be best to introduce such a database, starting with targeted pilot projects that focus on certain sectors like natural resources. Sierra Leona seconded Russia’s view and believed that a MAP database could help the country benchmark its treaty interpretation practices, while also noting that MAPs often involve sensitive information on tax treaty positions. Uganda, who had already emphasized the importance of transparency in dispute resolution in previous sessions, supported a database compiling MAP decisions which would allow leveraging some of the principles and decision making in past disputes to settle new similar disputes.

Many delegates, including France, Singapore and Norway, were however sceptical. They argued that especially in transfer pricing matters, APA and MAP are highly fact-specific and the grounds and decisions are not easily transferable to other cases. Domestic law often strictly prohibits the disclosure of such information. Norway noted that MAP decisions are usually very brief and do not contain much detail on the decisions, which may make disclosure not very useful. China noted that disclosure would in any case require consent by both the taxpayer and the two countries involved.

Previous updates (3)

15 Aug 2025: Second round of negotiations closed with debates on the early protocol on disputes prevention and resolution

From Wednesday to Friday, negotiations on the early protocol for dispute prevention and resolution focused on scope, design, and balance between fairness and efficiency. Most countries agreed it should cover cross-border disputes, though some noted the overlap with domestic cases like transfer pricing. A key divide emerged over scope: Global North states favoured limiting the protocol to disputes under the UN framework, while Global South delegations pushed for broader coverage to address gaps in their limited treaty networks. On design, OECD members promoted strengthening the Mutual Agreement Procedure with mandatory binding arbitration, while many developing countries opposed this, citing sovereignty and capacity concerns, and instead advocated mediation, joint audits, and advance pricing agreements. There was general openness to opt-in/opt-out flexibility, though Southern countries warned that too much optionality could weaken effectiveness and pressed for minimum standards. Overall, the debates reflected persistent North–South divides: developed countries prioritizing certainty and arbitration, and developing countries stressing equity, access, and preventive mechanisms.

21 July 2025 Member States make written submissions on Workstream III Co-Lead’s Draft Issue Note

Country submissions showed both common ground and sharp divergences. Most states agreed that the protocol should focus on cross-border disputes, with purely domestic cases left to national systems. There was broad recognition of the need to improve access for countries with limited treaty networks, particularly in the Global South, where capacity and information asymmetries exacerbate disputes. On scope, Global North states often preferred limiting mechanisms to disputes under the new UN framework, while some Southern states argued for broader coverage, including existing treaty and transfer pricing issues. A key fault line was arbitration: many OECD countries supported mandatory binding arbitration to strengthen the Mutual Agreement Procedure, while most developing countries opposed it, citing sovereignty, capacity constraints, and power imbalances, instead favouring mediation or preventive measures like joint audits, APAs, and risk assessment. On optionality, most countries accepted flexible opt-in/opt-out approaches, but Global South voices stressed the need for minimum standards to prevent fragmentation and ensure fairness.

27 June 2025 Draft issue note published by Workstream III Co-Leads (Jamaica and Germany)

The scope of the issues under the proposed Draft issue note is broad, covering both structural design choices and practical mechanisms for resolving tax disputes. Key debates include whether the protocol should apply only to cross-border disputes or also domestic ones; whether it should be limited to disputes under the UN Framework Convention and its protocols or provide broader access to dispute resolution for existing tax rules; and how to strengthen or reform the Mutual Agreement Procedure (MAP), including whether to introduce mandatory binding arbitration or mediation. It also addresses the role of investment and trade arbitration (ISDS) in tax disputes and whether the protocol should restrict forum shopping by multinational enterprises. Another central area is dispute prevention, with proposals for advance pricing agreements, joint audits, cooperative compliance, and better information exchange. Finally, the protocol must decide on the degree of optionality—whether countries can opt in or out of certain mechanisms, or whether minimum standards should be mandatory for all signatories

Analysis💡

Tax Justice Network’s analysis – 14 Oct 2025

From a Tax Justice Network perspective, the negotiations on the early protocol on dispute prevention and resolution revealed progress in acknowledging the failures of current mechanisms but also clear gaps that mirror the Tax Justice Network’s long-standing concerns. The broad agreement that the protocol should focus on cross-border cases both under the current rules like transfer pricing and new rules under the Convention is welcome. Global South delegations are right to stress that their limited treaty networks currently leave them without access to effective mechanisms. OECD countries’ push for mandatory arbitration only deepens these asymmetries, while the Tax Justice Network underlines that arbitration entrenches power imbalances and should be rejected. Instead, the Convention should use this opportunity to “emancipate” dispute resolution from tax treaty bilateralism, creating a universal legal ground for mutual agreement procedures under the UN framework, similar to how information exchange has moved beyond bilateral treaties. During the negotiations it became furthermore clear that many unresolved disputes stem from fundamental disagreement on the fair allocation of the tax base under transfer pricing rules. The Tax Justice Network’s submission therefore highlights that prevention is as vital as resolution: moving away from the separate entity approach and transfer pricing toward unitary taxation and formulary apportionment would not only allocate taxing rights more fairly but also drastically reduce disputes. The protocol is also an opportunity to prohibit the use of investor-state-dispute resolution (ISDS) under investment treaties to deal with tax disputes by agreeing that tax disputes can only be resolved through tax dispute resolution mechanisms under the Convention. In any case, progress depends on shifting negotiations from optional, non-binding language toward a common normative framework under the Convention that guarantees inclusive access, prioritises prevention, and strengthens resource mobilisation for all countries.

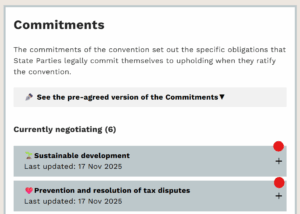

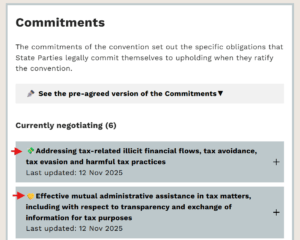

Commitments

The commitments of the convention set out the specific obligations that State Parties legally commit themselves to upholding when they ratify the convention.

✒️ See the pre-agreed version of the Commitments▼

From the Terms of Reference adopted by the UN:

Commitments

10. The framework convention should include commitments to achieve its objectives. Commitments on the following subjects, inter alia, should be:

(a) Fair allocation of taxing rights, including equitable taxation of multinational enterprises;

(b) Addressing tax evasion and avoidance by high-net worth individuals and ensuring their effective taxation in relevant Member States;

(c) International tax cooperation approaches that will contribute to the achievement of sustainable development in its three dimensions, economic, social and environmental, in a balanced and integrated manner;

(d) Effective mutual administrative assistance in tax matters, including with respect to transparency and exchange of information for tax purposes;

(e) Addressing tax-related illicit financial flows, tax avoidance, tax evasion and harmful tax practices;

(f) Effective prevention and resolution of tax disputes

Currently negotiating (9)

📬Exchange of information

Last updated: 9 Feb 2026

Explainer🧠

Exchange of information (EOI) is a cornerstone of international tax cooperation because it determines whether tax authorities can obtain the data they need to correctly assess and enforce taxes when income and assets cross borders. Unlike many other areas of international taxation that still rely heavily on bilateral tax treaties between two countries, exchange of information is one of the areas where a large number of countries have already moved to multilateral cooperation, including through the OECD/Council of Europe Convention on Mutual Administrative Assistance in Tax Matters, which provides for information exchange across modalities and is described by the OECD as the most comprehensive multilateral instrument for tax cooperation.

Exchange of information is not a single mechanism but a set of modalities that respond to different enforcement needs: exchange on request (case-linked information requested by one authority), spontaneous exchange (information shared proactively when it may be relevant to another authority), and automatic exchange of information (AEOI) (regular, standardised bulk transmission of predefined datasets, such as financial account information).

Placing automatic exchange of information within this broader toolkit matters because offshore secrecy and cross-border asset concealment are not solved by any one modality alone: automatic exchange of information can help prevent the problem from worsening, but it has not eliminated the harm, and access to automatic exchange of information has often been shaped by standards and participation conditions that do not fully reflect the realities of all countries. For the UN Framework Convention to create universal and inclusive standards so that all countries can benefit, the commitment needs to recognise different levels of administrative capacity and allow non-reciprocity—so that countries with the greatest need for information are not excluded simply because they cannot immediately provide the same volume or type of data in return.

Negotiation updates 🤝

9 Feb 2026: Equity, Reciprocity, and the Shape of Article 10

The Day 4 discussion on exchange of information (Article 10) centred on whether the Framework Convention should contain a standalone commitment with some core substance, or whether exchange of information should remain folded into the mutual administrative assistance commitment (Article 9) and be operationalised almost entirely through protocols. A broad coalition of developing countries and regional bodies argued that a standalone exchange-of-information commitment is necessary precisely because existing arrangements have not delivered equitable access in practice, with some delegations warning that importing current asymmetries would undermine the credibility of the Convention for countries that need cooperation most.

The most ambition-preserving intervention came from the African Group (Zambia), which supported having a shorter, less technical standalone article but argued it should still embed an implementation-oriented principle that can evolve through Conference of the Parties (COP) guidance, protocols, or other instruments—explicitly treating “foreseeable relevance” as a standard that can be revisited rather than a fixed ceiling. The AG also highlighted practical problems some countries face with “foreseeable relevance” being applied restrictively by counterpart jurisdictions, and proposed redrafting capacity language so it enables implementation (including through COP guidance) rather than reading as a limitation. Senegal supported the AG line and pushed for careful drafting of the refusal/limitations clauses, including deleting one sub-paragraph for clarity and ensuring the core obligation is stable and not unnecessarily narrowed by examples. Nigeria likewise aligned with the AG, arguing that not all states can join existing frameworks and that the Convention should avoid importing their shortcomings, while ATAF endorsed the AG approach and framed exchange of information as essential for combating illicit financial flows and supporting domestic resource mobilisation. Tanzania aligned also with the African Group (AG), stressing that uneven reciprocity and responsiveness in current standards constrains developing countries’ ability to benefit, while Kenya emphasised that “taking into account” existing standards does not mean adopting them wholesale. Morocco and Uganda also supported a standalone article, while flagging that parts could be kept general and improved through protocols.

A second cluster—largely OECD and like-minded delegations—pressed to water down the text by reclassifying Article 10 as “too operational” for a framework convention, urging either deletion (moving substance to protocols) or a high-level cross-reference to “existing standards”. Ireland, Poland, Belgium, Spain, France, Switzerland, Canada, Germany, Italy, Portugal, Norway, Israel, Japan, Singapore, and Indonesia returned to overlapping concerns: (i) a preference to keep exchange of information within Article 9 or in protocols rather than in a detailed standalone article; (ii) strong insistence on retaining the “foreseeably relevant” standard to prevent “fishing expeditions” and protect taxpayer rights; (iii) warnings about duplication with existing mechanisms (often referencing the Global Forum and the Multilateral Convention on Mutual Administrative Assistance); and (iv) repeated calls to clarify interaction with other instruments under the Convention’s relationship provisions (Article 15). The UAE and the UK signalled they could accept a standalone article only if it was rewritten at a high level, with the UK explicitly arguing that reopening established work (e.g., CRS) is not desirable and treating “foreseeable relevance” as a rights-related safeguard. Algeria broadly endorsed the AG but diverged by supporting retention of “foreseeable relevance” and raising scope/administrability concerns (including on coverage and burdens for lower-capacity administrations).