Nick Shaxson ■ If tax havens scare you, monopolies should too. And vice versa.

Europe Needs a “Tax Justice Network for monopolies.”

Introduction

The BBC recently carried a short article which began:

“Luxembourg’s data privacy watchdog says it is in discussions with Amazon about voice recordings made of customers who have used the firm’s Alexa smart assistant. The regulator is the “Lead Supervisory Authority” (LSA) for the company in the EU, meaning that it co-ordinates investigations into the business on behalf of the other member states.”

You may have heard stories about Alexa listening in on users’ sex lives, its occasional bursts of creepy laughter, the peculiar jokes, the story of the customer who was reportedly told to “Kill your Foster Parents,” and more. So it’s heartening to think there’s a watchdog out there, keeping tabs.

But Luxembourg? Anyone familiar with tax havens knows immediately that this monster corporate tax haven is about the last place you’d want to host a watchdog to curb abusive behaviour by large multinationals.

For those unfamiliar with Luxembourg’s role as a criminalised corporate tax haven at the heart of Europe, it’s worth reading up about the “Luxleaks” scandal (revealing the world’s biggest multinationals using Luxembourg as giant corporate tax-cheat factory;) or pondering Luxembourg’s sixth-place ranking in both the recent Corporate Tax Haven Index (CTHI) and its sister ranking of shame, the Financial Secrecy Index. Luxembourg’s stance goes back decades: consider, for instance, its central role in Bernie Cornfeld’s crime-infested Investors Overseas Services, or in the scandal of the Bank of Credit and Commerce International (BCCI,) arguably the rottenest bank in world history; its key role in the Elf Affair, Europe’s largest corruption investigation since the Second World War, in the Clearstream Affair; in Bernie Madoff’s still-unresolved Ponzi-scheme frauds; or in the Icelandic Kaupthing saga. To name just a few. As a searing Financial Times analysis summarised in 2017:

Luxembourg sometimes resembles a criminal enterprise with a country attached.”

Luxembourg’s national development strategies revolve around ‘competing’ to attract footloose global capital and the operations of multinationals, essentially by offering them an easy ride on taxes, disclosure, financial regulations, and criminal enforcement. These strategies, which have been called the ‘Competitiveness Agenda,’ are always harmful: in Luxembourg they have created a state whose political and regulatory machinery is captured by banks and large multinationals it hosts. This ‘competitive’ approach applies to data protection, as companies “forum-shop” for the jurisdiction most favourable to data firms. An adviser to multinationals explains:

Sophisticated organizations are structuring their decision-making functions concerning data in a manner which reflects a preferred enforcement forum strategy. . . . EU attorneys are seeing data planning exercises, somewhat similar to tax planning structures, emerging.”

The word “monopoly” refers to a market where there’s just one seller. There’s also oligopoly (only a few sellers), monopsony (only one buyer,) and so on. “Market power” covers these terms – and perhaps “coercive market power” is clearer. Sometimes ‘monopolies’ will be used as a loose general term, even if not strictly accurate.

Anyone familiar with ‘tax competition’ – a central issue for the tax justice movement – will recognise this language. It’s offshore business: this time not for tax, but for big data.

The location of these European Lead Supervisory Authorities (LSAs) shows a familiar pattern. Where is the LSA for Google? Ireland, another gigantic corporate tax haven. Facebook? Ireland again. Uber? The Netherlands, ranked fourth in the Corporate Tax Haven Index. Airbnb? LinkedIn? Microsoft? Ireland. And if you move beyond these privacy and data issues, to (say) cryptocurrencies, you find that the jurisdictions seeking to get ahead are places like Malta, an especially unsavory tax haven where dissidents against the offshore establishment get blown up with car bombs.

The overall result of this ‘data protection competition’? Well, in Alexa’s case, back to the BBC

It has not launched a formal privacy probe. [A spokesman for the Luxembourg watchdog said] “we cannot comment further about this case as we are bound by the obligation of professional secrecy.

Quelle (as the French say) surprise!

But now. What has all this got to do with monopolies? Well, we will get to that. The sections that follow necessarily starts by covering some widespread misconceptions about monopolies: that antitrust is just about ‘breaking things up;’ that it’s all about consumer prices; and that Europe doesn’t have much of a monopoly problem, or that its competition authorities are doing a good job.

Sections 2, 3 and 4 then lay out the scale of the issue, using both data and analysis, and Sections 5 and 6 cover some history, showing how we got here, and explores possible historical links between monopolies and fascism. It then, in Sections 7 and 8 we look at the several links between monopolies and tax havens, and the bridges between antimonopoly and tax justice, then follow this with

1. Myths and misconceptions

Monopolies are widely misunderstood, in several ways.

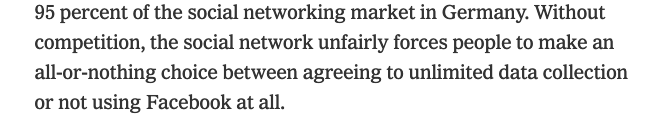

- Many people mistakenly think that monopolies are all about consumer welfare and prices. As in, a dominant player jacks up prices with impunity, and everyone pays more. No! Prices matter, but just think: Facebook’s and Google’s services are free! Amazon’s the cheapest! Consumer paradise! Yet if you think that their awesome dominance of the markets they are in — between them Facebook and Google have a stranglehold over two thirds of the $110 billion US internet advertising market — isn’t a problem, then you haven’t been paying attention. Price is the wrong metric here. Yet under the influence of Chicago Law & Economics, especially since the 1970s, this obsession with consumers and with prices has increasingly been the central guiding principle of antitrust law and enforcement, in the United States, in Europe, and elsewhere. The central problem isn’t prices, but private power.

- Many people mistakenly think that antimonopoly (or “antitrust,” as it’s sometimes known, for historical reasons) is all about “breaking things up” to increase competition. No. Breakup is just one (important one) from a spectrum of remedies. More competition in banking, for instance, won’t necessarily curb any banker’s willingness to take profitable risks at taxpayers’ long term expense: it could provoke an arm’s race to take most risks. Breaking up Google would help tame its power, but a bunch of smaller Googles may well do similar nasty stuff with our data. So remedies to corporate power must also involve better financial regulation, stronger tax laws, criminal laws, limited liability laws, accounting and audit rules, data protection and privacy rules, prison sentences, crackdowns on tax havens, and more. Exceptions need to be made for the ”little people”, who must be allowed to organise to confront corporate power. All this, and plenty more, can go in the antitrust box.

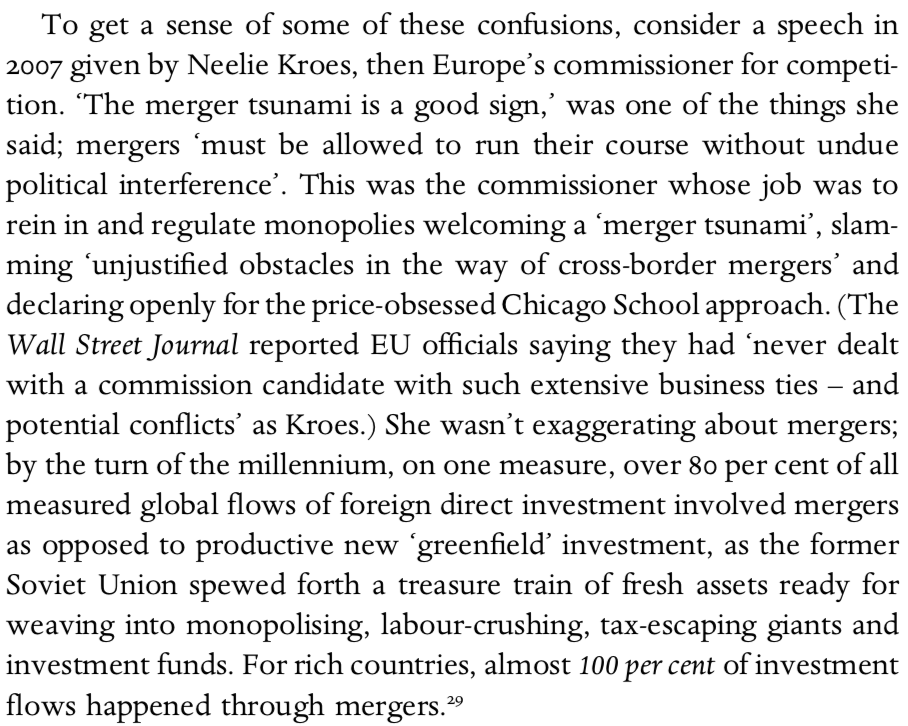

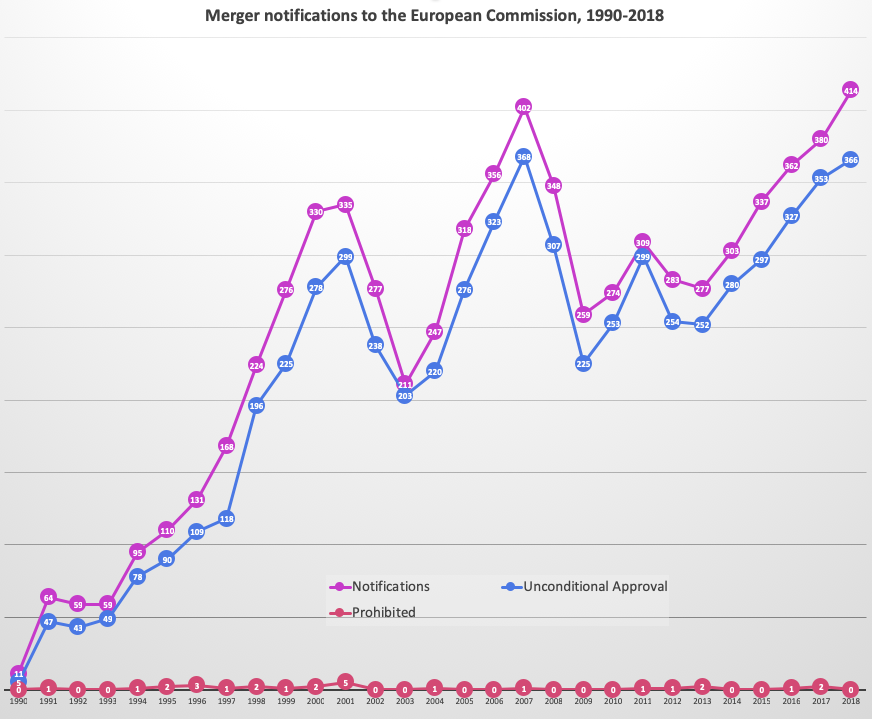

- It is widely believed that European competition authorities, under the leadership of Margrethe Vestager, are global monopoly-busting heroes. They aren’t. She’s a lot better than her appalling predecessor, Neelie Kroes, and Europe is surely doing a better job than the mess they’re making in the United States, and better still than the non-existent antitrust authorities in most poorer countries. But European competition authorities operate within a price-obsessed ideology and legislative framework, and under massive corporate influence in Brussels. (The graph in Section 9 provides a taster.) Some officials in Europe, such as Germany’s top antitrust regulator Andreas Mundt, have spine, but the list is fairly short.

- Many experts seem to think that the monopolies problem is an American disease: that it’s not much of a problem for Europe. Not so. Scroll down to Section 4 on Measuring Monopoly, or search in this blog for the words “false cornucopia”, to see how large and pervasive this is. Data can only measure some of its effects: there are many blind spots. What is more, power begets power, and without radical action soon the dangers will inevitably grow, and grow. The problems may be sharpest in developing countries, though there’s little data about this.

- People across the political spectrum oppose antitrust for various reasons. On some parts of the right, for instance, many people see big firms as efficient. On some parts of the left, there’s often a suspicion of competition and of markets: antitrust, for some, is seen as a tool to perfect capitalism, rather than to abolish it. Our response is this: monopolies, just like tax havens, involve rigged and corrupted markets. We advocate un-rigging and de-corrupting markets – whatever other policy proposals you may have.

- There is often great confusion (especially, it seems, in Europe) about the relationship between competition in markets between firms, on the one hand, and on the other hand tax and regulatory “competition” and the “competitiveness” of whole countries — the Competitiveness Agenda, as it has been called. These two processes with similar names are wholly different in the real world (ponder the difference between a failed company, like Enron, and a failed state, like Syria, to get a first sense of this difference.) The former kind of competition in markets is generally healthy, when it works, while the latter is always harmful. As the Tax Justice Network has pointed out repeatedly, policy-makers labour under elementary economic fallacies which means they conflate the two kinds, prioritising the latter as if it were the former. As the Alexa discussion above shows, this ‘competition’ inevitably promotes corporate subsidies, including lax antitrust.

In terms of civil society, a thrilling fightback has emerged in the past couple of years. But — and this is a big but — almost all the energy is in the United States. European civil society is all but asleep. Europe now needs to develop an expert, radical, snarling, non-partisan organisation, network and movement to create a deep, coherent critique, propose radical solutions at national and European levels, and to take the fight directly to the policy-makers.

More on all these soon. But for now, if you remember one thing about monopolies, make it this.

The problem isn’t about prices. It’s about power. And herein lies a key to the political extremism we’re now seeing everywhere.

2. A new gilded age: monopolies are everywhere

We are in a new Gilded Age of monopoly and coercive market power, across the world. Market-controlling behaviour by large corporations poses as great a danger to the world as tax havens do.

Monopolies — as with corporate tax avoidance, and the looting of national treasuries and the stashing of the proceeds in secret offshore accounts — thrive most happily in conditions of weak government. In a power vacuum, thuggish shake-down artists rise to the top. That’s why we think the problem is probably most acute in poorer countries. While there is little research in this area, there are plenty of stories if you look for them. Anyone familiar with Carlos Slim, who cornered Mexico’s mobile telephony to impose effectively a private tax system on Mexican phone users and become at one point the world’s richest man, or Aliko Dangote, the billionaire who dominates Nigeria’s all-important cement business (and much more besides), will know how big this issue is.

Seven of the top ten richest people – Amazon’s Jeff Bezos, Microsoft’s Bill Gates, the financier Warren Buffett, Mexico’s Carlos Slim, Oracle’s Larry Ellison (up to a point), Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg and Google’s Larry Page – are arch-monopolists, in each case taking a genuinely useful service then using market dominance as the central, wealth-extracting plank of their corporate strategies to multiply their wealth. (The other three enjoy considerable market power too.)

Market power and rigged markets: this is where the really big money is. All these people and their businesses, of course, also use tax havens extensively: once a wealth extractor, always a wealth extractor.

Monopoly is everywhere now. That false cornucopia of goods on your supermarket shelves: investigate who owns each brand, and the trail typically lead back to just a tiny handful of giants like Unilever or KraftHeinz or Mondelez.

Try the Too-Big-To-Fail global banks. There’s even an official list of these giants. They aren’t getting smaller – and a prospective “Amazonisation” of many financial functions may make things worse. Among other things, these giants have used oligopolistic practices to enjoy structural power in global capital markets, which (as Jerôme Roos has shown) have progressed from decentralised to more concentrated forms, helping creditors “act uniformly” to impose “a coordinated discipline” on borrowers, frequently poorer countries. Or try entertainment, where Disney has amassed so much market power that we are at last seeing the beginnings of a push to break Disney up. And so on.

All this is part of a broader phenomenon academics call “financialisation,” which also brings tax havens and monopolies together. Financialisation involves not just the growth of the financial sector, but also the conversion of underlying economic activities into financial forms. A private equity-like firm, say, identifies a market niche and buys up all the competitors in that niche, then extracts monopoly rents from their customers, workers, and suppliers — at the same time as also running all their affairs through tax havens, to gouge taxpayers.

The problem may be greatest in one particular sector.

3. Big Tech

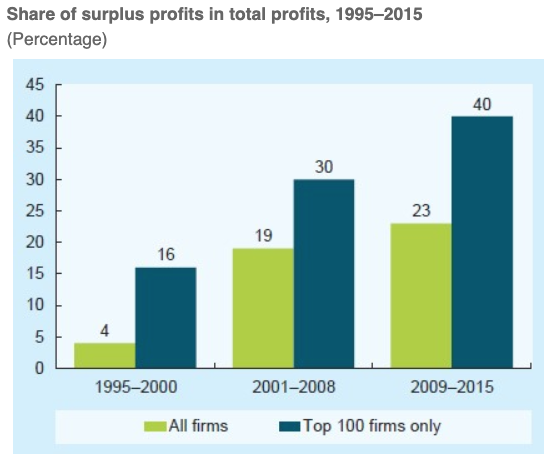

Facebook, which essentially has no direct competitors, leverages its market power to force users into devil’s bargains where they have little choice but to hand over their data to infamous “third parties” if they want this awesome convenience.

Then there’s Google, which has similar market power:

Having effectively coerced your data from you, these firms feed it into algorithms ”designed to prioritise engagement” which consequently spread propaganda and hatred, tilt elections, worsen health crises, exacerbate global warming by spreading conspiracy theories and helping the forest-killing Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro into power – and who knows what else?

If you think social media is diverse, Instagram, Whatsapp, and many others are owned by Facebook. Youtube? Google. The Android operating system? Google (which is the default search engine, and they also pay Apple to be the default on iPhone. Deepmind? Google (OK, Alphabet, which is Google.) Your sunglasses? Gigantic market power, courtesy of EssilorLuxottica. The business of academic papers? Same again. Rail transport? Huge market power, gouging taxpayers and travelers. The water you drink? Maybe it’s under a local water monopoly. The news you consume? Filtered through those same gargantuan controlling internet giants with the power to influence what gets read. Hell, even the Helvetica, Times New Roman, Palatino and other typefaces you use are being taken over, would you believe it, by the market-power-hunting private equity firm HGGC.

As Mariana Mazzucato and many others have pointed out, the problems spewing from Big Tech won’t be fixed just by breaking them up and injecting a dose of competition, (though that, if smartly done, would help.) As already mentioned, there’s a lot more to antimonopoly than that.

4. Measuring monopoly

We can only ever measure parts of the monopoly problem. After all, what dollar price would we put on the Facebook-fueled Cambridge Analytica scandal? But here are a few indicators.

First, two thirds of all global corporate earnings now reportedly come from firms with annual revenues of $1 billion or more, according to McKinsey. These giants don’t just overwhelm competitors: governments cower before them. One could argue that entire societies are in Google’s, Facebook’s and Amazon’s thrall.

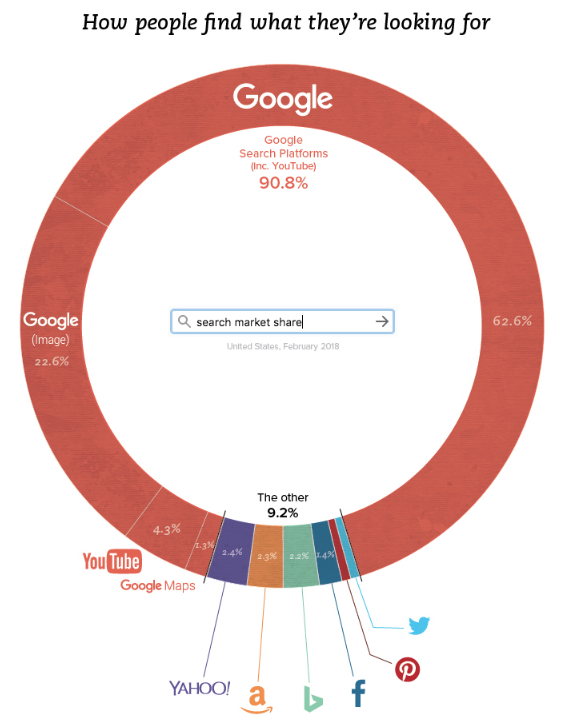

Second, look at “surplus profits” (meaning, roughly, what you’d expect: a measure of rigged markets, perhaps.) It’s getting worse, worldwide:

Surplus profit likely doesn’t capture it all. Amazon, for instance, didn’t make a profit for years: instead of returning cash to shareholders it ploughed it back into buying up (and muscling out) competitors, dominating markets, building monopolies. The threat they pose is in their capacity to strangle other perfectly viable businesses – a threat that “surplus profits” doesn’t measure.

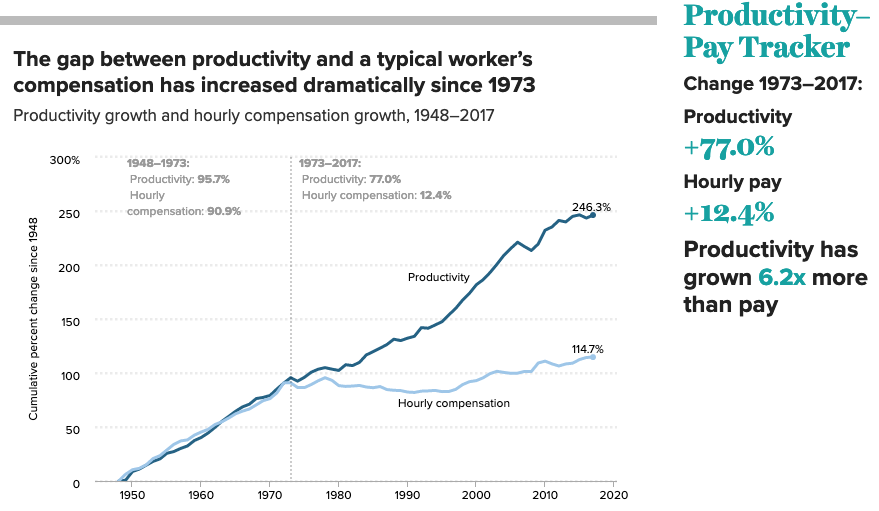

Third, see this recent research paper by Simcha Barkai of the University of Chicago Booth School of Business, who investigated one of the great puzzles of US economics. Why has the productivity of American workers soared over the last 30-40 years, while those workers’ incomes have stagnated?

Is this divergence because of technology? Globalisation? Or is it down to the rise in market power and monopoly? (Or, to be precise here, monopsony, when it’s buyers of labour, rather than sellers, who have the market power.)

Barkai burrowed into what corporations do with the money they earn. It turns out there has been a dramatic decline in the share being invested in labour costs – but also an even bigger decline in the share going to capital costs (investment in factories, etc.). What has risen, to compensate for these declines, is profits: money returned to shareholders. He said:

only an increase in markups can generate a simultaneous decline in the shares of both labor and capital”

And the effect is big — really big. The rise in profits has been about $14,000 per worker (in 2014) — worth about half of median income! As he put it, “an increase in competition to its 1984 level would lead to large increases in output (10%), wages (24%), and investment (19%.)”

This represents both a staggering transfer of wealth, and an overall loss of wealth too. Imagine how different the political landscape in the United States would be if all (or even a big chunk) of that rise in profits had gone to workers instead of to owners. (And if those conspiracy theories hadn’t found such wonderful, monopolising transmission vehicles.)

A new book by finance researcher Thomas Philippon has some other numbers: improving competition would:

- Save US householders $600 billion a year

- Increase GDP by $1 trillion

- Increase private labour income by $1.25 trillion, while cutting corporate profits by $250 billion

Away from the United States, studies have also found:

- the average global markup has gone up from 1.2 in 1980 to around 1.7 in 2016. (De Loecker & Eeckhout, 2018)

- The rise in the capital share of income in Europe is twice as large as recorded in the official accounts (Tørsløv, Wier, Zucman, 2020 update.)

- Business churn in Europe is falling, as fewer new entrants emerge. (Guinea/Erixon, 2019)

- In Europe, the ten largest companies control, on average, over 80% of the market in postal, air transport, broadcasting, telecommunication, and water transport in each national market. (Guinea/Erixon, 2019)

- A ‘neoliberalisation’ of European competition policies (Buch-Hansen and Wigger, 2010)

- A surge in mergers & acquisitions led by private equity and other financial players (Wigger, 2012)

- A dramatic drop in companies in the U.K. sharing profits with workers (Bell, Bukowski, Machin, 2018)

Matters in Europe may not be as extreme as in the U.S. on many measures, but they are extreme, and the research is sparser.

Note, once again, that prices are just one measure of the problem: monopolies (like tax injustices) generate inequality, economic stagnation, de-industrialisation, financialisation, a loss of entrepreneurship, corruption, and threats to national security.

And there is another dimension of damage to know about.

5. Older history and the f-word

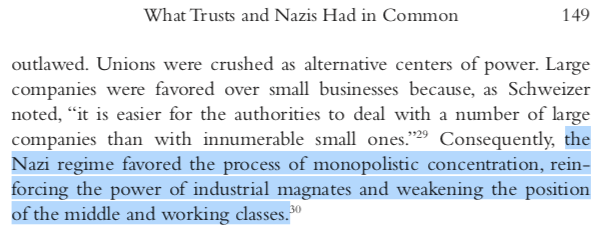

Historically, monopolies have been associated with authoritarianism and even fascism. Tax havens seem to have similar associations.

Why? Well, for one thing, healthy competition with multiple players competing in markets implies dispersed economic and political power. Central control via monopolies naturally fits with authoritarianism. As Jonathan Tepper and Denise Hearn note in their excellent antimonopoly book The Myth of Capitalism:

(Here’s another study looking at that.) When the Second World War ended, the US-led Allied powers restructured the German political landscape under the three D’s: De-Nazification, De-Militarisation, and De-Cartelisation. A massive re-assertion of competition in the US economy, and to a lesser extent elsewhere, alongside other progressive policies such as high taxation of the wealthy, strong financial regulation and powerful restrictions on cross-border financial flows co-incided with what is now known as the “Golden Age of Capitalism”, a high-growth age which lasted for a generation after World War Two.

During this period, capitalism and democracy were more or less aligned. Bosses paid workers who produced goods, which generated profits. Competition and open markets kept excesses in check, and helped workers bargain with bosses, to get a fair cut of the profits. All paid their taxes, and the rich often paid very high rates. Finance was kept under control too. Economic growth in most countries was higher than at any point in world history, before or since. Politicians accepted democracy.

That golden age has given way to tax havens, monopolies and other market-rigging schemes which pit a corrupted capitalism against democracy. The ensuing unfairness and inequality has generated vast pools of anger. And, to detract from that anger, the winners from the system use the tried-and-tested tricks of the demagogue: deflect attention by blaming the poor, or people of colour, or sausage-eating Euro-weenies in Brussels. And if democracy fights back – well, the politicians’ answer is to reject it.

6. Where did the modern monopoly problem come from?

Antimonopoly zeal has risen and ebbed over the centuries, most obviously in the United States, (as this timeline shows.) The US has always, rightly or wrongly, identified itself as a standard-bearer for freedom — but for long periods of its history American society recognised that tyrants come in both public and private forms.

If we will not endure a king as a political power, we should not endure a king over the production, transportation, and sale of any of the necessities of life,” said the monopoly-busting US Senator Sherman around 130 years ago. “If we would not submit to an emperor, we should not submit to an autocrat of trade.”

True freedom needs strong official fences against private predators — or you’ll get the wrong kind.

To put it a different way, powerful government intervention may be needed to keep markets clean and open, just as football games need referees and linespeople to keep play fair.

American antimonopoly laws during periods of healthy competition tended to frame the problems not so much in terms of price, but in terms of two other things: on curbing excess concentrations (and abuses) of power; and on watchfully protecting the structure and integrity of markets.

After the 1960s, however, a small handful of scholars at Chicago led by Aaron Director, Robert Bork and Richard Posner, narrowed antitrust down to consumer welfare and prices, by scoffing at the idea that big corporations would monopolise (seriously, they did argue this) — and then going on to say that it could be a good thing if they did monopolise! These, and other changes, spread not just into the Republican Party, but also into the Democratic Party, to the courts — and from there to Europe and the rest of the world.

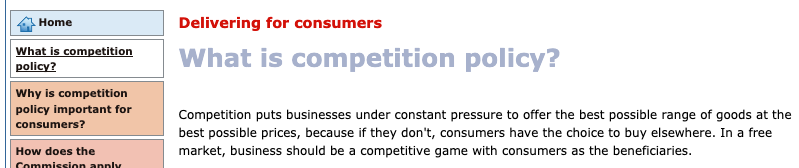

Now, for instance, European laws have been heavily captured by this price-obsessed view of monopoly. Here’s the top of the highest-level official public statement on European competition policy.

Note the obsession with prices and with consumers. Lower down, this section targets “state-run monopolies” (but not, explicitly, private ones) and even states baldly that “mergers are legitimate” as long as they “expand markets and benefit consumers.”

The European approach is also predicated heavily on tackling “abuse of a dominant position” – which sounds great. Much better, though, would simply be to tackle “dominant position.” Once they’re dominant, it may be too late to get a grip on the abuses that ensue.

This is not a citizen-friendly antitrust system.

7. Where do antimonopoly and the anti tax haven movement connect?

There are several areas where tax havens and monopolies overlap. This section looks more at how this might happen in the domestic economy: the next section focuses in more detail on some crucial particular global dimensions.

Most broadly, both phenomena involve the rigging and corruption of markets, to extract wealth from a range of stakeholders. With monopolies, they rig markets by directly dominating them, while tax havens help large firms escape profit-crimping rules they don’t like. In each case, political ‘capture’ to facilitate the market-rigging is essential. In each case, a dangerous “shareholder value” ideology justifies the extraction, at the expense of wider society.

What is more, private empires built around one form of unproductive wealth extraction or market-rigging are likely to stem from the same corporate culture which encourages the pursuit of other forms. Once a wealth extractor, always a wealth extractor. It’s surely no coincidence that Amazon doubled its reported US profits in 2018 – at the same time as it reported paying zero federal taxes – in fact, it got a $129 million rebate.

Third, both monopolies and tax havens shift entrepreneurial energies in an economy away from improving productivity (by, say, producing better goods and services in cleverer ways), towards these unproductive wealth-extraction games. A recent analysis of the US economy by Thomas Philippon and German Guttierez showed that while modern “superstar firms” are highly profitable, they don’t contribute to productivity in the way that past superstars (like General Electric or General Motors) once did. And, Philippon adds, “The big difference between the superstars of today and those of the past is that superstar firms today pay much less taxes.”

Tax haven activity (whether via helping multinationals cut their tax bills, or helping them escape financial regulations,) also reinforces monopolising trends. (As a leading campaigner in this area put it, “Taxpayer subsidies help build monopoly.”) This is partly because it boosts corporate profits, making large firms (the main users of tax havens) even larger, boosting their abilities to buy up competitors. This, again, has nothing to do with genuine productivity or entrepreneurialism. Also, corporate tax cuts reduce the cost of capital relative to labour, thus incentivising them to cut labour’s share in national income (which we discussed above.) This hurts workers – while further boosting monopoly. As recent research summarises:

“A drop in the corporate tax rate reduces the labor share by shifting the distribution of production towards capital intensive firms. Industry concentration rises as a result.”

Likewise, this goes in the other direction. Monopoly reinforces tax injustice. For one thing, the bigger and more international a company is, the more easily it can expand into more jurisdictions, thus making it easier to shift profits around to dodge tax (or to escape other constraints,) further boosting profitability. And there’s evidence this happens: as a new paper shows:

Our findings reveal a striking and persistent tax advantage for big business since the mid-1980s . . . relative to their smaller counterparts.

It’s a self-reinforcing dynamic which connects with another: the lobbying power to browbeat states into changing tax laws in the multinational’s favour. The best example of all this may be Amazon’s widely-reported efforts to engineer a “Hunger Games environment” to create ‘competition’ between US states to host its second headquarters, in which it sought to squeeze maximum subsidies and tax breaks out of the states. This was a major issue for antimonopolists and tax justice activists alike.

Here is another way that monopolisation boosts tax injustices. Corporate tax cuts can, in the right circumstances, be passed on to consumers, or to workers, or pensioners, shareholders, or other stakeholders of a firm. But the bosses of a firm with market power will have just that — power to pass tax cuts through to shareholders — the financial owners of the company — but also to pass tax hikes on to anyone except shareholders. To have their cake and eat it. (New IMF research shows, for instance, that this is a major reason why President Trump’s tax cuts have been so poor at generating jobs and investment: it’s been shareholders who snaffled the cream.)

8. Value chains and choke points

A further way to think about monopolies and tax havens is to consider how multinationals string “global value chains” around the world, generating economic value in one set of countries (for example, by setting up factories there) then sitting astride strategically positioned choke points in global markets, to extract additional profits from the chain. As corporate tax lawyer Clair Quentin explains it:

the things we buy are cheap because of cheap hyper-exploited labour abroad, we all know that, but the cheapness of that labour does not necessarily mean greater profits for the company actually employing the cheap labour. It is much more likely to mean greater profits for whichever “lead firm” (to use the global value chains jargon) is “governing” the value chain. . . making excess profits by using its governing position in the chain to force those other firms’ prices down.”

If the choke point is a powerful one, they can not only push down prices for producers (using their monopsonist power) while also pushing up prices for consumers, getting a double dose of rentier profits. These outsized profits are easy to de-materialise as financial capital and shift into what Quentin calls “swollen sacs of undertaxed capital” in low-regulation, no/low-tax tax havens. And the drivers of this offshoring of profits are also the drivers of centralisation. As one commercial analysis puts it:

“The commercial and legal drivers to consolidate ownership of a group’s intangible assets, and the tax advantages from doing so in a low tax environment, have resulted in the prevalence of structures designed to centralise the global or regional ownership of intangibles.”

These concentrated pools of financial capital offshore are vantage points in their own right: pots of mobile money to dangle in front of workers or suppliers or tax authorities in different countries, allowing multinationals to play each off against the others by threatening to pull out investment (or not to invest) from each place, so as to obtain maximum advantage at the expense of all the other stakeholders in the game. What is more, by using these tricks to shift profits into tax havens, the local subsidiary of the lead firm can easily make artificial losses – then tell workers “we’re not profitable – so, sorry folks, but there’s no money for wage increases.” When, in truth, there is an immense amount of money in those swollen sacs of undertaxed capital, out of reach, offshore.

This can lead to bloodshed. In a report on South Africa’s Marikana massacre in 2012, for instance, police fired on miners demanding wage increases, killing or injuring nearly 100 people. A subsequent investigation by South Africa’s Alternative Information and Development Centre (AIDC) found that: “Terminating the Bermuda profit shifting arrangement could have released R3 500-R4 000 extra per month for a Rock Drill Operator wage” – [which would have covered the protesters’ original demands and prevented the protest.]

In these global strategies the lead firms obtain both escape – the tax haven thing – but they also accumulate and concentrate power in global markets (the monopolies thing.) The power enables the lead firms to intimidate and cheat both tax authorities and politicians, but also workers and others.

All this means more slippery capital floating around the world that’s hard to tax, regulate or bring under democratic control and accountability.

These games are easier to play in the digital age. In the old industrial economy, “smokestack” industries usually required large capital investments in factories and the like to generate profits. Would-be monopolists had to make gargantuan investments, often in multiple factories rooted to the ground, if they wanted to corner and control physically dispersed markets (though it did happen). Now, however, a growing share of corporate profits are realised by internet platforms and other choke-point-straddling firms which require relatively little capital investment (Uber doesn’t own cars, Airbnb doesn’t own apartments, and Google doesn’t own newspapers: these platforms free-ride off large investments and effort made by others.)

To illustrate how this can work, take a patent, which tax wonks call an ‘intangible asset.’ Patents and copyrights are state-sanctioned mini-monopolies, where you’re officially allowed to keep competitors out of a market niche you’ve created or bought into. (There are old, good justifications for the idea of copyrights or patents, but thanks to legal changes like the Mickey Mouse extension and ceaseless lobbying, protections that used to apply for a few years can now extend for a century or more.)

Patents, company brands and other “intangible” assets are bread and butter for those designing multinationals’ tax haven schemes. To oversimplify, here’s how it’s done.

- A multinational sets up a shell company subsidiary in a tax haven, to own Patent Y and Brand Z.

- That subsidiary charges other parts of the multinational company, elsewhere, large royalties for using Patent Y and Brand Z.

- Those large cross-border royalty payments turn up as high profits in the tax haven, where the tax rate is zero, while in the high-tax country those payments are treated as costs, reducing tax payments there too. Hey presto! The multinational’s tax bill shrivels and disappears.

The international tax system also encourages monopolisation. Under principles enshrined a century ago, multinationals are treated as if they were collections of separate entities, all trading with each other across borders in independent arm’s length transactions. But as a new report explains, multinationals in the real world draw great strength and profit from their nature as unitary global entities, reaping tremendous market power and economies of scale which makes them far more profitable than a bundle of genuinely separate entities ever could. Multinationals’ accountants concoct fictional “transfer prices” for these cross-border internal transactions, thus shifting profits across borders in the direction of tax haven-based subsidiaries.

What is more, even if you were to find a multinational trading on the basis of genuine “arm’s length” prices, the fact is that those “governing” lead firms have the choke-point power to suppress the price of genuinely value-bearing inputs in the open market anyway. In other words, if the multinational’s accountancy arm don’t manipulate those transfer prices to cut the tax bill, the multinational’s monopsony / monopoly arms will. (For more on this, see here.)

An alternative international tax system promoted by the tax justice campaigners (and others), called Unitary Taxation with Formula Apportionment, would, if effectively, applied, decisively address these issues, treating multinationals like the unified powerful behemoths that they are, realigning tax with economic substance, and in the process curbing their market power. This should be considered as both an antitrust tool and a tool for tax justice. Fortunately, this system is at last gaining traction in policy circles – though as Quentin notes, there are some big questions about global value chains still to be addressed: notably how to apply the unitary / formula approach to global value chains.

Another obvious bridge between antimonopoly and the anti tax haven movement concerns the vast accounting and professional-service firms like PwC, Deloitte, EY or KPMG. Their size allows them to milk profitable conflicts of interest between different functions, contributing to a thoroughly corrupted form of capitalism. These companies are cheerleaders for and facilitators of monopolising mergers & acquisitions — and they play a similar role offshore: perhaps no other group carries as much responsibility for designing the nuts and bolts of global offshore architecture of tax havens, and for lobbying governments around the world to change their tax (and regulatory) rules and laws in ways that tend to reinforce large corporates, against wider society. As one summary puts it, the Big Four accounting firms:

“are actively facilitating the consolidation and concentration of corporate power . . . through their intimate knowledge and ability to work the international financial system, [they] are aiding in aggressive tax minimisation that ultimately undermines democratic government; implicitly supporting dubious financial regimes and other forms of sleaze.” 9. The euro-competitiveness fallacies

NOTE: We are singling Europe out here – not because it’s the worst actor but because many people think there’s no problem here. But there is. Not only that, but Europe holds keys to global trends.

In all these areas, Europe has played a strange, conflicted, and confused role.

On the one hand, the European Union seeks to portray itself as a bastion of progressive economic policies and defence against neoliberalism – and there certainly is a fair bit of that – with the result that the problem is generally sharper in the United States and elsewhere than in Europe. As Philippon said of global antitrust trends:

Europe—long dismissed for competitive sclerosis and weak antitrust—is beating America at its own game.

Indeed, Europe is also where probably the most explicit bridge between antimonopoly and tax justice has been created, with European competition authorities under Vestager taking Ireland to court over its refusal to collect €13 billion in back taxes from Apple. The underlying logic is that Irish tax rulings for Apple constituted unfair “state aid” – tax subsidies – which rig markets by giving selective advantages to Apple and undermining competition. Ireland wasn’t the only culprit: the same state aid tool has also targeted the tax haven affairs of Luxembourg, the Netherlands and the UK.

The logic that tax haven schemes constitute state aid is correct, so it’s encouraging that Europe is trying to wrest billions from a market-rigging multinational and return it to the people. Yet beyond this point European policies are incoherent and prey to corporate capture. A recent book gives a taster (p110 here, disclosure: your correspondent authored this book):

Kroes was later implicated in the Panama Papers tax haven scandal. Vestager, her successor, is of course a very different actor: in fact Kroes even criticised Vestager’s stance on Apple for being (cue tiny violins) “unfair.”

Yet despite Vestager’s apparently fresh approach, she still operates largely under old, price-obsessed frameworks. Her speeches reflect this, and her office, like those before her, may have vigorously prosecuted cartel behaviour in some areas, but it has also nodded through a string of gigantic monopolising mergers, many of which should never in a million years have been tolerated:

Even the prohibition against ‘state aid,’ the foundation of the generally welcome case against Apple and Ireland, is problematic: state aid rules effectively prohibit European nations from supporting and nurturing selected domestic industries: industrial strategies that nations have since the industrial revolution used as springboards for successful economic development.

This gets us into complex waters, and more Euro-confusions.

Vestager has called for Europe to “tear down the technical and regulatory barriers“ that keep Europe’s markets fragmented. The idea here is that if you have a single seamless market then there will be lots of European competitors jostling in every national market, thus increasing local competition. But more often than not the practical outcome has been the replacement of dominant national players with even larger, more powerful dominant pan-European players — or yet bigger global players like Amazon operating from lax-regulation, low-tax European platforms like Ireland or Luxembourg.

And Europe also, with help from little-known lobbying groups such as the European Roundtable of Industrialists, suffers from a bad old economic idea called supporting “national champions” to go head-to-head with the Chinese, or the Americans, or the Japanese, in the name of something called “European competitiveness.” Proposals are out there for a €100 billion European wealth fund to support such giants.

It’s a compelling story: who could disagree with a need for Europe to be “competititive”? Well, anyone who has read the Tax Justice Network regularly will know that once you unpack the concept, it soon reveals its incoherence.

The idea of relaxing competition rules to allow global behemoths to emerge, is really the old Competitiveness Agenda. Such ‘champions” would be bolstered by market power allowing them to exploit European consumers, workers, taxpayers and others, sto help them “compete” better on the world stage. Or, to summarise more succinctly:

make Europe more ‘competitive’ by reducing competition in Europe.

If that sounds ridiculous, it’s because it is. It’s the same basic idea used to justify multinational corporations’ use of tax havens: let them use tax havens to extract wealth from taxpayers, so as to make the multinationals — and by extension Europe — more ‘competitive.”

Robbing Peter (taxpayers) to pay Paul (the multinationals) is not a viable recipe for progress.

This isn’t the place to dissect Europe’s competition policies in detail, though. The main point of this article is to point out that — with a few disjointed exceptions — there is no serious pushback coming from European civil society against this: no coherent critique being made.

10. A global fightback is underway

The good news is that the fight against monopolies is, just like the fight against tax havens, something that can garner support all across the political spectrum, from people on the political Right who worry about the rigging and corruption of markets, to people on the Left who fret about overwhelming corporate and financial power and the rise of inequality. “I hate to admit it,” the Fox News commentator Tucker Carlson said last year, commenting on Amazon, and echoing many others on the Right, “but [the avowedly socialist] Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez has a very good point.” As the US expert Matt Stoller puts it, antimonopolism is “not some lefty crusade or right-wing attempt to seize power.”

Indeed, a nascent antimonopoly movement is now rising fast. Its epicentre is in the United States, where groups such as the influential Open Markets Institute, whose journalists combine deep expertise with uncompromising, even snarling radicalism, are spearheading a revival of old antitrust ideas, leavened with new ones for the digital age. These ideas have moved into the policy platforms of leading politicians such as Elizabeth Warren or Bernie Sanders: in fact, to pretty much all the main Democrat candidates, a move away from the Obama era when Google lobbyists all but had the keys to the White House. Here’s Google CEO Eric Schmidt — the one who said he was proud of his company’s tax-cheating ways, (“it’s called capitalism”) — wearing a Clinton campaign staff badge in 2016.

There has been some, though less, interest from Republicans, some of whom want to revitalise their party’s conservative, open-market roots.

The new antimonopoly is starting to spread east across the Atlantic, helped by front cover reports in The Economist and columnists like Rana Foroohar writing for The Financial Times.

As a sign of possible Euro-changes, it may be significant that those European merger prohibitions, running at close to zero for most years since 1990, ticked slightly upwards in early 2019, with a proposed Tata Steel/ThyssenKrupp merger blocked, along with prohibitions on an Alstom/Siemens tie-up, along with surely the most ghastly proposition of them all: Commerzbank with Deutsche Bank. Germany’s regulators are coming out swinging at Big Tech, in some cases at least. A very current example concerns a proposed “Nachunternehmerhaftung Gesetz” (don’t you love those German words) – draft legislation to level the playing field in the parcel delivery industry. (Read more here.)

However, European competition policies are a still mishmash of thinking, with no coherent counter-narrative. There are the German “Ordoliberals” (who believe that competition must be let rip, with a strong state as referee;) the Chicago Law & Economics movement, where the rule of law is subjugated to questions of economic efficiency; there is French state-led dirigisme; there is the ubiquitous Competitiveness Agenda (see above) and the national-champions brigade; there are components of the political left who decry monopolism as simply an inevitable result of capitalism, which must be overthrown — and by all sorts of special pleadings by various Euro-nations.

Yet if European competition policy is currently mixed up, it will be more easily dislodged in the right direction if everyone sings from the same hymn sheet. So there’s all the more reason to set up a truly progressive expert network to take on the monopolitis that seem to be sprouting everywhere.

Fifteen years ago, the year after the birth of the Tax Justice Network, Jeffrey Owens, the head of tax at the OECD, expressed his frustration with the lack of civil society action on tax havens until then, but raised a new hope:

“The emergence of NGOs intent on exposing large-scale tax avoiders could eventually achieve a change in attitude comparable to that achieved on environmental and social issues.”

In pretty short order, a new tax justice movement began to help drive massive changes to the international tax haven system.

Europe needs a new antimonopoly movement, a home-grown version of groups like the Open Markets Institute, fighting for a radical antimonopoly agenda, firing off broadsides in the media, submitting legal challenges, educating journalists, and above all unpicking the corrupt antitrust consensus from first principles, then putting it together into a large, coherent, expert structural critique — and proposing world-changing solutions.

Here are just a couple out of of a thousand examples of radical possibilities. Ban all advertising targeted on personal information. (Crazy? Maybe. But Just think of the democratic dividend. Is anyone in Europe running with this?) Why is there no movement in Europe cheering on Vestager and urging her to go further, when she says she is thinking about shifting the burden of proof onto Big Tech companies’ shoulders, in competition cases? This idea came from a panel of experts: we need ideas like this gushing forth from an independent body fighting for ordinary people.

This blog is a first attempt to make the links with the tax justice movement, and to show how much overlap there is with our issues. The Marikana massacre suggests just how many different agendas can be at play here – and how many allies and constituencies might be brought together for this fight against market-rigging and overwhelming corporate power.

Someone needs to start setting up a new body to engage on these cross-disciplinary issues and to start creating a coherent, expert and radical critique of where we’ve got to.

And they need to do it, fast.

Further reading:

Cornered, by Barry Lynn. “The Velvet Underground was a band about which it was said that they didn’t sell a lot of records, but everyone who bought one started a band. Similarly, Lynn didn’t sell a lot of books, but everyone who bought a copy became an advocate.” A touch out of date now, but still a bible for many.

The Myth of Capitalism, by Jonathan Tepper and Denise Hearn. (Like the Finance Curse book, on the Financial Times, Best Books of 2018.) More up to date, and if anything, scarier, than Lynn’s.

Open Markets Institute. Sign up for their newsletters, and why not donate? (Disclosure: I have no affiliation with Open Markets.)

The ”Big” Newsletter. By Matt Stoller. Regular updates on antimonopoly, mostly from the US but with lots of international news too.

Related articles

‘Illicit financial flows as a definition is the elephant in the room’ — India at the UN tax negotiations

Democracy, Natural Resources, and the use of Tax Havens by Firms in Emerging Markets

The Financial Secrecy Index, a cherished tool for policy research across the globe

Do it like a tax haven: deny 24,000 children an education to send 2 to school

Tax Justice transformational moments of 2024

The State of Tax Justice 2024

Indicator deep dive: ‘Royalties’ and ‘Services’

Indicator deep dive: Public country by country reporting

Profit shifting by multinational corporations: Evidence from transaction-level data in Nigeria

5 June 2024

What is the place of Transfer Pricing in this tax haven arrangements?

Thank you, particularly for the many useful references.

(Small quibble about ‘epicentre’, in what is mostly an agreeably written piece)