Nick Shaxson ■ Russia’s offshore financial nexus, threatening financial stability and security

We have for years remarked on the role of the offshore system in promoting financial instability, not least for its propensity to enable financial players to get out from under financial regulations they don’t like, then taking the cream from risky activities and shifting the risks onto others. Now, from Izabella Kaminska at FT Alphaville:

“Where did Russia’s 2014 crisis really come from? City University’s Anastasia Nesvetailova has penned a fascinating paper looking at the question.”

Well, she’s right: this really is a fascinating paper. (She spoke about this at our City University London event in June.)

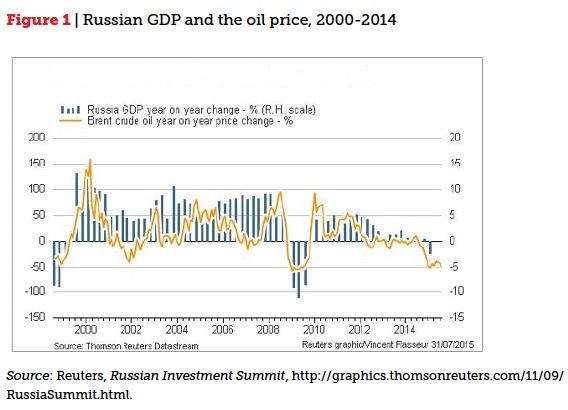

A fall in oil prices is clearly one reason for Russia’s economic crisis, as this graph from Nesvetailova’s paper suggests. Kaminska again, summarising:

“It may be Russia’s complex and increasingly financialised economy — including its connections to an offshore nexus — which may prove a greater threat … financial channels which once underpinned the success of Putin’s Russia now work as crisis transmission mechanisms instead.”

The growth in Russia’s financial sector (or ‘financialisation) brought President Putin temporary economic stability — but masking progressively greater economic fragility, as debts grew. And alongside this ‘financialisation’ (related to our “Finance Curse” thesis) is a third factor of crisis, of particular interest to us. As Nesvetailova puts it:

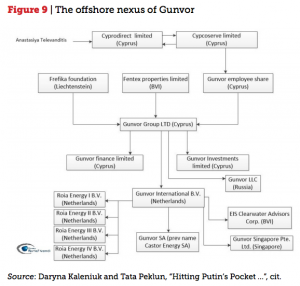

“Here we come to the third major aspect of the internationalisation of the Russian economy and crisis transmission mechanism, namely, the problem of capital flight, and more specifically, the offshore nexus of Russian capital.”

And some essential context and more fascinating detail:

“It is hard to overestimate the role of the offshore havens network, a peculiar remnant of the British Empire, both for the Russian owners of capital, as well as for Western financial centres. Access to offshore ownership envelopes has enabled Russian owners to avoid the post-Crimea sanctions. Offshore havens have also been benefiting the City of London in the current crisis, as money flowing out of Russia is not being recycled back into Russia but is invested in Western financial and property assets. (With the exception of Crimea, which in 2014 saw an upsurge of foreign investments from Cyprus, the BVI and other offshore havens, led by inflows from Guernsey which accounted for 80 percent of all FDI into Crimea in 2014).”

Round Tripping

She takes a look at that “foreign direct investment” in more detail. Tax havens and secrecy jurisdictions routinely try to claim that they “channel” and “help attract” investment into large ‘onshore’ economies – but in reality so much of what they do is really ’round tripping: local investors going offshore where they can dress up in financial secrecy and pretend to be foreigners in order to attract tax breaks and avoid scrutiny and so on. And this fosters not just tax evasion but makes all sorts of Ponzi-like behaviour, corruption and criminality possible. Nesvetailova:

“Although nominally part of the BRICs and deemed an emerging market with great potential for capital, Russia had never become successful in attracting foreign investment . . .Russia has mostly been attracting Russian capital, with few non-Russian investors seizing the opportunities for capital growth.

. . .

The data suggests that it is the capital of Russian-owned structures, recycled out of Russia through a chain of offshore jurisdictions that has been recycled back into Russia as FDI

. . .

As Ledyaeva et al. find in their study of investment round-tripping in Russia, round-trip investors tend to favour flows into the service sector, tend to establish manufacturing firms in resource-based industries and support the development of corruption in Russia.”

“All of which suggests a level of inter-entity lending and borrowing reminiscent of the shenanigans that went on at Enron.”

Nesvetailova explains the mechanisms, which are significantly transfer pricing games:

Nesvetailova explains the mechanisms, which are significantly transfer pricing games:

- A Russian company belongs to a Cyprus “mother.” The Cyprus company gives its Russian “daughter” a loan (or a right to use the brand name, licence, etc.). The Russian company sells products in the Russian market and earns revenue. Most of this revenue goes to paying off the Cyprus mother (either as interest on the loan or as a fee for the title/right/royalty). As a result, the net profit of the Russian daughter is minimal, most of the sum goes to Cyprus.

- A sub-type of the same model is based on exports: a Russian company sells products to a Cyprus firm at a low price. The Cyprus company in turn, sells products to the final consumer at a higher price. In reality, these are only recorded “paper” transactions; the products go directly from Russian producer to final consumer. [TJN: that’s known as ‘re-invoicing.’ We suspect it is a very large phenomenon among developing and emerging economies in particularly, though estimating its scale amid all this secrecy with any degree of accuracy is, we feel, impossible.]

And what is the purpose of all this? Well,

“Typically, in advanced economies, offshore structures are used to conceal profits flows. In Russia, intricate chains of offshore based entities are constructed with the aim of hiding the ultimate ownership of assets. In Russian offshore “envelopes,” Cyprus has historically been a popular node of initial incorporation of the offshore entity, which in turn would have financial and legal links to other financial havens in order to be able to tap into the onshore financial systems of Europe and North America.”

(Of course there is plenty of “hiding the ultimate ownership of assets” in advanced economies too.)

Putin is now, as we’ve noted previously, involved in an ‘anti-offshore’ drive. A charitable interpretation would see this as a way of crackdown on harmful and unpopular but widespread corruption (and, in part, it surely is.) But many Russians see a different motive at play, which is often present in anti-corruption drives:

“The anti-offshorisation campaign launched by Putin, while apparently aimed at raising state revenues, can also be interpreted as the state’s drive to control the key nodes of Russian business.”

The Ponzi dynamics fostered by opaque offshore ownership; the build-up of debt fostered by increased financialisation and openness to the global economy, alongside offshore incentives for criminality and corruption, all, as Nesvetailova puts it: “pose serious political-economic risks.” (Indeed they do: offshore poses serious security risks for may countries, as we’ve noted.)

She puts forward several scenarios for how this is going to play out:

- oil prices rebound, and things settle down

- stresses from the fall-out of crisis further fracture Russian élites, generating political instability

- the economic crisis worsens; “Russia is financially rescued by China and becomes a (resource) satellite of China. This merger starts a global realignment of powers and geopolitics. Some developments indicate that such a re-alignment has already began.”

- Russia returns to the Western fold and an inevitable modernisation path.

- The Kremlin attempts to distract attention from the deepening economic crisis by entering into another security conflict, either by further escalating the ongoing war in Ukraine, or by heightening the security situation domestically through pro-Kremlin militia.

Somehow, it seems to today’s TJN blogger that the more worrying options here appear the more likely.

Related articles

Taxing Ethiopian women for bleeding

Tax justice and the women who hold broken systems together

What Kwame Nkrumah knew about profit shifting

The last chance

2 February 2026

The tax justice stories that defined 2025

Let’s make Elon Musk the world’s richest man this Christmas!

2025: The year tax justice became part of the world’s problem-solving infrastructure

Bled dry: The gendered impact of tax abuse, illicit financial flows and debt in Africa

Bled Dry: How tax abuse, illicit financial flows and debt affect women and girls in Africa

9 December 2025