Nick Shaxson ■ Two new reports challenge the OECD’s work on corporate tax cheating

The OECD, the club of rich countries that dominates international tax, is running a project known as Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) which is supposed to fix some of the gaping holes in the international tax system. As we all know, transnational corporations (TNCs) are running rings around even the best-resourced tax authorities, and the OECD, responding to pressure from governments and civil society, are trying to do something about it.

An international network of tax researchers and academics has been set up, called the BEPS Monitoring Group (BMG), with the support of civil society groups, including TJN, and coordinated by Prof. Sol Picciotto, a Senior Adviser to TJN. The BMG aims to evaluate and respond to the proposals resulting from the BEPS process, as well as putting forward alternatives. It has just published two more reports, each looking at recent important proposals produced by the BEPS project:

The submissions include both explanations and general comments, as well as more detailed points which are probably only of interest to connoisseurs of international tax. As the reports help to show, the basic principles of what’s going on are quite straightforward, as explained below.

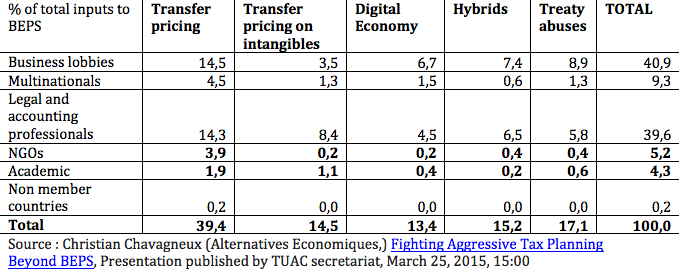

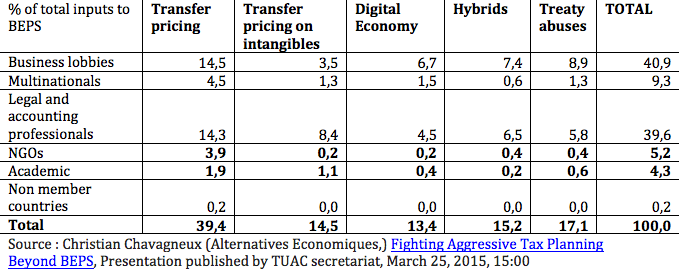

But first, look at this table showing how heavily outgunned we are, in terms of influencing BEPS:

Controlled Foreign Corporation rules

Unitary tax

The separate-entity principle is a fiction, and we have argued that a better model is to treat the TNC as it really is: a unitary group under common control, which presents a single set of global accounts, allowing profits to be allocated to different countries where it operates according to how much genuine economic activity goes on there. Each country can apply tax at its own rate to its allocated portion of global profits.

One of the central features of the international tax regime overseen by the OECD, a club of rich countries, is the so-called ‘separate entity’ principle, which treats transnational corporations (TNCs) as if they were loose collections of separate entities operating in different countries, with each taxed separately by the relevant country. The principle is a fiction (see box), and in practice this ‘separate entity’ principle encourages TNCs to create a web of subsidiaries in convenient jurisdictions, inside its own corporate structure, to shuffle profits across borders to suit its tax affairs.

One of the tools that tax authorities have devised to tackle the problems posed by the separate entity principle is the ‘controlled foreign corporation’ (CFC) rules. In effect, these rules override the separate entity principle and effectively allow a tax authority to say ‘you have that subsidiary in a tax haven: we are going to tax it anyway as a CFC even if it is supposedly located out there in the tax haven.’ CFC rules can be adopted by countries acting alone, and about half of OECD countries have done so, but this leaves them open to pressures from TNCs, which threaten to move to countries without such rules. These are empty threats, as it is hard in practice for TNCs to move their real headquarters.

However, a number of countries such as the UK have watered down the rules after heavy lobbying by TNCs. The changes introduced in 2012 were estimated to cost the UK £1 billion, but the charity Action Aid estimated the cost to developing countries at £4 billion. Coordination is therefore essential to stop this race to the bottom, but so far the OECD has failed to provide it.

What does the BMG say about the state of play on CFCs? The basic principles are simple:

“CFC rules should act as a deterrent removing the incentive for MNEs to shift profits out of source countries. To achieve this however, they must be set at a high standard and coordinated. A weak standard which is left to states to implement would be counter-productive, as it would encourage source states to reduce their tax rates, and hence worsen the race to the bottom in corporate tax.

. . .

Strong CFC rules could give the BEPS project some chance of success, but weak rules would mean its failure.”

This is important stuff, and despite the technical challenges, civil society groups need to get strongly behind these recommendations. Otherwise – just look at that lobbying muscle . . .

Read more about the details in the BMG submission.

Mandatory disclosure

This requires less explanation. This concerns legislation in some countries where, if a company is going to put in place a tax scheme, it is legally required to disclose it to the local tax authorities: for example the UK’s DOTAS (disclosure of tax avoidance schemes) system. BMG explains the core problem:

“Legal requirements for disclosure in advance of schemes for tax avoidance are a useful instrument for tax enforcement. However, in most countries where they have been introduced they affect mainly small and medium enterprises and wealthy individuals, and do not cover most avoidance by large multinational enterprises (MNEs). This is because they target standard schemes which are widely marketed by promoters, whereas MNEs generally use arrangements tailored to their specific needs.”

For examples, in the Luxleaks scandal, it turns out that rubber-stamp tax clearances by PwC in Luxembourg over a period of eight years for 343 TNCs were not notified under the UK’s DOTAS requirements.

The BMG set of recommendations on this (summary here and full report here) look at other issues, including the problematic fact of ‘cooperative compliance’ – or sweetheart deals.

Related articles

Bled dry: The gendered impact of tax abuse, illicit financial flows and debt in Africa

Bled Dry: How tax abuse, illicit financial flows and debt affect women and girls in Africa

9 December 2025

The millionaire exodus myth

10 June 2025

The Financial Secrecy Index, a cherished tool for policy research across the globe

Indicator deep dive: ‘Royalties’ and ‘Services’

Inequality Inc.: How the war on tax fuels inequality and what we can do about it

Proposal for ‘Business in Europe: Framework for Income Taxation’ (BEFIT): A wrong turn in the right direction

2 February 2024

Formulary apportionment in BEFIT: A path to fair corporate taxation

31 January 2024

New Tax Justice Network podcast website launched!