Alex Cobham ■ The Brexit tax haven threat – rescinded?

Back in January, the UK Chancellor of the Exchequer (the finance minister), Philip Hammond, used an interview with the German newspaper Welt am Sonntag to raise what has become known as the Brexit tax haven threat: if the EU doesn’t give the UK a good deal, the UK will lead a race to the bottom to undermine the EU on tax and financial regulatory standards.

Now, in an interview with Le Monde, the Chancellor has rowed back on that threat – giving the first open acknowledgement that the UK’s ‘recognisably European’ social, economic and cultural model depends on taxation. But even aside from the deep splits within the UK government, it remains unclear whether even Mr Hammond himself is clear on what he means:

“It is often said that London would consider launching into unfair competition in terms of fiscal regulation. That is not our project or our vision for the future… The amount of tax that we raise, measured as a percentage of GDP, is within the European average and I think we will remain at that level. Even after we have left the EU, the United Kingdom will keep a social, economic and cultural model that will be recognisably European.”

We welcome the UK government’s apparent recognition of the importance of tax – but the UK Chancellor’s latest interview seems to reflect fundamental intellectual confusion at the heart of the Brexit project. And while the threat is a largely hollow one, given the EU’s power to limit the impact there, it has the potential to worsen significantly the costs that Brexit will impose on UK citizens.

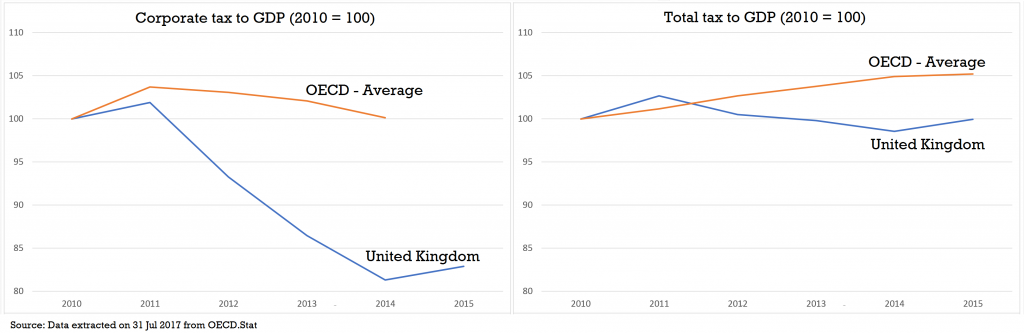

The Chancellor makes the claim to Le Monde that the UK is ‘in the middle of the pack’ in terms of its tax take. But the truth is that the UK has been racing to the bottom: from a tax take above the OECD average in 2011, to almost two percentage points below that average in the most recent data. And most dramatically, the UK’s corporate tax take as a share of GDP fell from the OECD average in 2010, to just 80% of the (unchanged) OECD average in the most recent data.

In his most recent budget, the Chancellor committed the UK to continue cutting its corporate tax rate even after it’ll have the lowest of any G20 country, and even when the government’s own figures show clearly that there is no benefit from doing so – just billions of pounds of revenue sacrificed during a time of harsh cuts to public services and social welfare.

The Chancellor also told Le Monde that the UK has no plans for ‘unfair competition’ in terms of regulation, and argued that the EU should support financial services operating from London because the alternative was that major US banks “will move their activities back to Wall Street, which is particularly attractive given that the U.S. administration is in favour of deregulation and cutting taxes.” This comment underlines the confusion about whether tax and regulatory ‘competition’ is consistent with a positive economic and social model, or in fact opposed to it.

It also sits at odds with the UK government’s decision, announced just last week, to overrule its own regulator in order to seek to take market share from Bermuda and other small financial centres in the issuance of catastrophe bonds and related securities.

And so, the British Chancellor’s statement may prove to be the first step towards rescinding the Brexit tax haven threat to the EU. But rhetoric alone will not reverse the UK’s race to the bottom, nor protect its citizens from the costs – not least, in terms of higher inequality and weaker governance.

Related articles

‘Illicit financial flows as a definition is the elephant in the room’ — India at the UN tax negotiations

Democracy, Natural Resources, and the use of Tax Havens by Firms in Emerging Markets

The Financial Secrecy Index, a cherished tool for policy research across the globe

Do it like a tax haven: deny 24,000 children an education to send 2 to school

Tax Justice transformational moments of 2024

The State of Tax Justice 2024

Indicator deep dive: ‘Royalties’ and ‘Services’

Indicator deep dive: Public country by country reporting

Profit shifting by multinational corporations: Evidence from transaction-level data in Nigeria

5 June 2024