Bob Michel ■ Indicator deep dive: Public country by country reporting

We recently published the latest update to the Tax Justice Network’s Corporate Tax Haven Index, which is a ranking of the countries most complicit in helping multinational corporations underpay tax.

The index ranks countries by evaluating how much wiggle room for corporate tax abuse their laws provide and by monitoring how much financial activity conducted by multinational corporations enters and exits the countries. Laws are evaluated against 18 indictors.

In this blog, we’ll do a deep dive on one of those indicators – the Public Country by Country Reporting Indicator – and the key findings it reveals.

What does the indicator do?

When a country does not require all multinational corporations to report their revenue, profits, taxes, staff and tangible assets for each country where they have affiliates, corporations can shift their profits to tax havens, conceal this information within their consolidated accounts at the group level, and underpay tax.

This indicator assesses if the country requires multinational corporations incorporated within its borders, listed on national stock exchanges, or involved in certain sectors to make public their worldwide financial reporting data on a country by country basis.

Why public country by country reporting?

Public country by country reporting is one of the key corporate transparency policies the Tax Justice Network has been long advocating for. Its an accounting practice designed to expose a multinational corporation whenever it shifts its profit into tax havens to pay less tax than it should.

Country by country reporting regimes come in different shapes and sizes. In the previous edition of the index (developed in 2020 and published in 2021), the emphasis laid on measuring the extent to which countries were embracing public reporting. For example, countries received good marks if they adopted a single sectoral regime and better marks if they adopted various regimes for various sectors. This approach was in line with policy situation of the day: while many countries had adopted the OECD’s standard of non-public country by country reporting developed under BEPS, few legislators had ventured into embracing public reporting rules. Public disclosure of country by country reports is however the only way of solving the flaws of the OECD’s confidential reporting standard. Not only does this standard often leave low-income countries out of the information ‘circle’ because they are unable to implement the burdensome exchange of information standards, it also denies countries access to information on multinational corporations that are remotely doing business within their borders but without a taxable presence. Furthermore, non-state stakeholders like citizens, consumers, investors, academia and civil society all have valid interests in transparency on multinationals’ various local activities and local tax bills.

How does the indicator score countries?

The zeitgeist regarding wide scope public country by country reporting has drastically changed since the Corporate Tax Haven Index was last updated. The adoption of the EU Public Country by Country reporting Directive at the end of 2021 shows that many countries hosting multinational headquarters are no longer opposed to economy-wide public country by country reporting. For this reason, the focus of the indicator has now shifted from measuring the quantity of regimes in place to measuring the quality of public reporting regimes in place. Under the updated methodology, three factors are key for determining the quality of a country’s public country by country regime: 1) whether the regime applies to all sectors (good score) or just a single sector (bad score); 2) whether a regime adopts a high information reporting standard by requiring information on assets, payroll, sales and profits/losses before tax (good score) or only limited information like just tax payments without other financial information (bad score) and 3) whether a regime requires full geographical disaggregation (good score) or allows the information on certain groups of countries to be reported in aggregated form (bad score). If countries have multiple regimes in place, their score is determined by the most optimal regime, which will be the regime that has the widest scope of application.

What do the indicator’s latest results reveal?

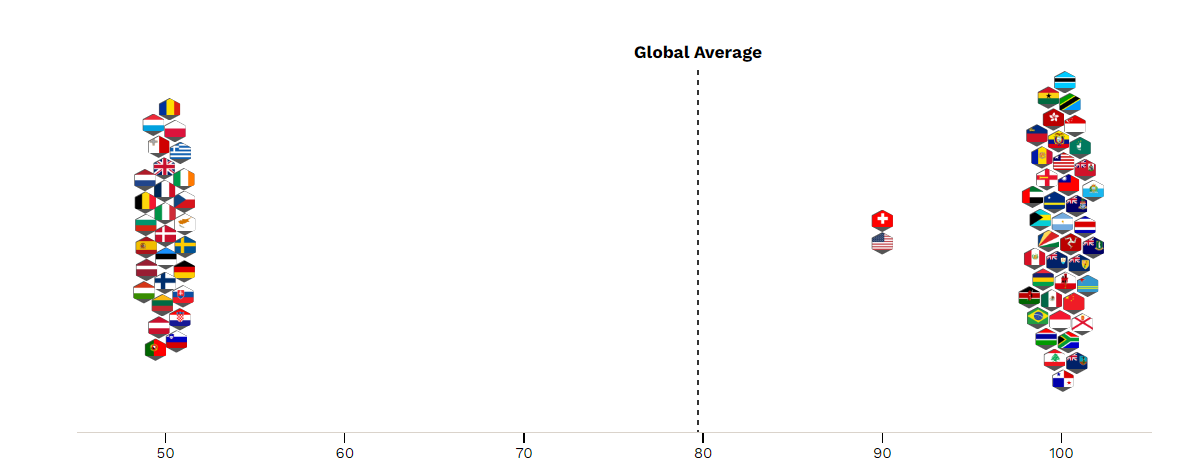

On the surface, countries’ scores on Public Country by Country Reporting Indicator don’t seem to have changed much. But there’s more going on underneath the hood.

The biggest change seen on this indicator took place in the EU. Twenty-four EU countries have now implemented the wide-scoped public country by country regime of EU Directive 2021/2101. Their scores, however, remain the same. In fact, they scored the same as the three EU countries that did not implement the new directive, namely Cyprus, Italy and Slovenia. How can this be?

While the regime of the new EU directive applies to all sectors, it does allow multinationals to aggregate country information from non-EU countries which are not listed as tax havens. This significantly restricts the directive’s reporting powers – and ultimately the directive’s impact – to the point of making the directive not particularly more effective than the older directive other EU countries are implementing. For this reason, implementing EU countries have not gained a score improvement on the indicator compared to the three EU countries that have not implemented the new directive.

Those three countries are scored for their implementation of the sectoral public reporting regime of the older EU Directive 2013/36 which applies only to banks and which was implemented by all EU countries some years ago. Under this older regime, only banks have to provide public country by country reporting but full geographical disaggregation of information is required, which leads to an identical score as the new regime.

So to put it simply, the new directive applies to all sectors (good!) but allows aggregated information (bad!). The old directive applies to just the bank sector (bad!) but does not allow aggregated information (good!). So implementation of either directive results in the same mixed-bag score.

If EU countries want to increase transparency (and see their indicator scores improve), they have to tick both boxes: public reporting in all sectors and without any aggregation of individual country information.

An additional note here: Analysis of EU countries’ transposition of the new directive shows that many EU countries are making use of the opt-outs allowed under the directive. These include the safeguard clause for commercially sensitive information, the lack of compulsory publication of the reports on a company’s website if published somewhere on a government website, and the absence of a penalty regime. These opt-outs are not treated as score-altering restrictions on the indicator (since the directive’s allowing of aggregated information is already a serious restriction), but they certainly do not increase the effectiveness of the new directive.

Last but not least, the indicator shows that a tiny but important bit of public reporting progress has been made in the United States. Like Canada, Switzerland and EU countries, the United States enacted a long time ago a public country by country reporting regime that applies to companies active in the extractive industries. This reporting regime, figuring in Section 1504 of the Dodd Frank Act of 2010, requires US multinational corporations active in the extractive industries to provide public country by country reporting on ‘payments to governments’. Alongside information on mining royalties, dividends, fees and a few other types of payment made to governments, information is also required on the amount of tax paid per country. However, US Big Oil companies have so far continued to successfully prevent the regime from being implemented by repeatedly challenging its implementation rules, both in court and in Congress, for nearly 14 years now.

But, a challenge-proof set of rules was issued in 2021 and the first reports are expected to be finally filed by the end of 2024, including by the Big Oil companies. The public filing of these reports will be a good day for corporate transparency, and arguably for the planet.

You can see countries’ scores on the Public Country by Country Reporting Indicator here. And explore all indicators on the Corporate Tax Haven Index here.

Related articles

The Bitter Taste of Tax Dodging: Starbucks’ ‘Swiss Swindle’

Disservicing the South: ICC report on Article 12AA and its various flaws

11 February 2026

What Kwame Nkrumah knew about profit shifting

The tax justice stories that defined 2025

2025: The year tax justice became part of the world’s problem-solving infrastructure

Indicator deep dive: ‘patent box regimes’

‘Illicit financial flows as a definition is the elephant in the room’ — India at the UN tax negotiations

Tackling Profit Shifting in the Oil and Gas Sector for a Just Transition

The State of Tax Justice 2025