Sergio Chaparro-Hernandez, Markus Meinzer ■ What happened at the first round of UN tax negotiations and what’s next?

Unprecedented, historic negotiations took place from 26 April to 8 May at the United Nations headquarters in New York. For the first time, the 193 Member States began discussing the parameters that will guide the negotiation of a United Nations Convention on International Tax Cooperation (UNFCITC). Civil society and other stakeholders were also able to publicly contribute their views to the negotiations under UN rules of procedure, bringing the winds of genuine democracy to international tax negotiations that have up until now taken place behind closed doors in spaces such as the OECD (see the Civil Society Financing for Development Mechanism’s comprehensive compilation of resources on these negotiations).

This blog summarises what happened in the first session of negotiations (from April 26 to May 8) and raises some considerations for the key decisions that the Ad Hoc Committee will have to make in the remaining period of its mandate. A second session of negotiations will be held from 29 July to 16 August on the final draft of the parameters, before they go to a vote at the UN General Assembly near year-end.

Why are framework conventions so important? Because they are binding instruments that provide the basis for the creation of a system of governance and an international legal regime in a specific field. Their nature can be better understood if they are thought of as a global constitution that serves as the basis for creating more detailed binding rules —called protocols— that make up an international legal framework. As such, the discussion on the terms of reference of a UN framework convention on international tax cooperation is a golden opportunity to lay the foundations for an international tax framework that overcomes the structurally embedded, racialised inequalities in decision making power that the world has inherited from the imperial and colonial dynamics with which the current rules were decided (see top-level UN experts formal communication to the OECD on this matter).

Resolution 78/230 adopted in 2023 by the General Assembly mandated an Ad Hoc Committee to finalise the terms of reference (ToR) that will govern the negotiations of a UN framework convention on tax by August 2024. This is as important a task as the negotiation of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) was, whose provisions have laid the foundation for international climate cooperation with significant implications for present and future generations. As happened with the framework convention on climate change, the defining of the parameters of the UN framework convention on tax will have significant implications for the scope, speed and timeliness of international cooperation on global tax for the decades to come, ultimately shaping how the costs and benefits of international tax policy play out for future generations (see our previous blog on why the world needs UN leadership on global tax policy).

So how did the negotiations go?

A show of tactics lacking good faith

It’s important to emphasise that it took a historic, overwhelming, global south led victory at the UN last year for these negotiations to take place at all. That victory came in the form of legally binding decision taken by the UN General Assembly to begin these negotiations, starting first this year with negotiations on the terms of reference and culminating next year with a framework convention. The scope and focus of the negotiations were also agreed as part of this binding decision. A landslide majority of countries – home to 80 per cent of the global population – voted in favour of the decision, outnumbering those against by more than 2 to 1.

With a legal mandate now established to negotiate and pursue the adoption of a framework convention on tax, and clear decisions on what these negotiations should entail, pushback from countries who voted against the decision was expected to reasonably focus on watering down the terms of reference and securing the weakest version possible of a framework convention. Shamefully, pushback from some countries during the negotiations went beyond what could be considered in good faith. Several tactics were employed by some countries to negotiate not the terms of reference but to attempt to reopen, undermine and disregard the binding legal decision agreed last year.

In his 2023 report, the UN Secretary General presented to the UN General Assembly, as he was requested to do by the assembly, three options for making international tax cooperation fully inclusive and more effective. He noted that if the option of a framework convention (as opposed to a standard convention or a non-binding framework) was adopted by member states, it “would outline the core tenets of future international tax cooperation, including the objectives, key principles governing the cooperation and the governance structure of the cooperation framework”. The report also clarified that framework conventions “may also include institutional provisions for creating a plenary forum for discussion between States that is endowed with the authority to adopt further normative instruments to which States could then become a party”.

With the adoption of Resolution 78/230, the General Assembly opted to initiate an intergovernmental process that should culminate with the adoption of a Framework Convention, and as such it gave a precise mandate to the Ad Hoc Committee to elaborate the terms of reference for such an instrument. This mandate is binding for the 125 Member States that voted in favour of Resolution 78/230, as well as for the 48 that voted against and the 9 that abstained (see the positions that countries adopted on the Tax Justice Policy Tracker and the voting records here).

While states may have diverse negotiating positions and legitimate concerns about the process, the first round of negotiations that just took place shows that some states are still betting on carrying over into this stage discussions on issues that have already been decided, and as such should not be taking place if states are negotiating in good faith.

Among these obstructionist tactics that hinder the fulfilment of the Ad Hoc Committee’s mandate, and against which member states and other actors in the process must be vigilant, were:

- Disregarding or generating confusion about the clear mandate to move towards a Framework Convention. This ranges from positions that still speak of a preference for a non-binding framework to those that disregard the constitutive character of a Framework Convention by restricting its ability to pursue its own objectives. The recurring argument by the minority that voted against Resolution 78/230 that the Convention should not duplicate or be inconsistent with existing instruments, for example, ignores that a Framework Convention, aims to “establish an overall system of tax governance” (see Secretary General’s report, par. 55) and as such can redefine the substantive and procedural pillars of existing and future instruments.

- Limiting the scope of the task ahead and of the Convention to be negotiated to the point of disregarding the mandate of the Ad Hoc Committee. Advocating for a minimalist Convention with objectives such as “gather countries to exchange effective practices on mobilising domestic resources” (see several EU submissions) instead of outlining the core tenets of international tax cooperation, is also another way of ignoring the constitutive character of a Framework Convention and thus pushing for the definition of parameters for the stage that are contrary to the mandate of the Ad Hoc Committee.

- Denying the motivation or other provisions of the resolution that has given rise to the work of the Ad Hoc Committee. As recognised in the UN Secretary-General’s report “existing international and multilateral arrangements […] do not satisfy the main elements for fully inclusive and more effective international tax cooperation”. Resolution 78/230 stated that an intergovernmental process at the United Nations for tax norm shaping and rule-setting would “leverage existing strengths and address gaps and weaknesses in current international tax cooperation efforts and arrangements”. While the Resolution mentions that this should be done “with full consideration of existing multilateral and institutional arrangements”, it also recognises that “inclusive and effective participation in international tax cooperation implies that procedures should take into account the different needs priorities and capacity of all countries to meaningfully contribute to the norm-setting processes, without undue restrictions”.

A corollary of this is that if Resolution 78/230 is motivated by the importance and timeliness of strengthening international tax cooperation to make it fully inclusive and more effective, both in procedural and substantive terms, then being faithful to that mandate implies overcoming the problem of the lack of both full inclusiveness and effectiveness of existing instruments identified by the Secretary-General’s report. In this vein, refusing to reform and reconsider existing rules on the grounds of avoiding duplication and complementarity, when they fail to meet the values put forward by the General Assembly, is to deny the motivation behind the mandate given to the Ad Hoc Committee. - Insist on changing well-established decision-making rules. All procedural provisions must be based on compatibility with the rules that are specific to the spaces where discussions take place. It is important to distinguish three distinct stages: 1) the Ad Hoc Committee’s decision-making rules for drafting the terms of reference (ongoing), 2) the Ad Hoc Committee’s decision-making rules for negotiating the Convention, and 3) the decision-making rules of the Framework Convention itself. In the first two cases, since the task will be performed by subsidiary bodies of the General Assembly, the established practice is that while consensus is sought, simple majority rule is not ruled out. A minority of states have argued that established practice should not apply when it comes to the Ad Hoc Committee’s decision making due to the alleged exceptionality of the nature of tax matters. Instead, they argued that decisions can only made on a consensus basis. The arguments for alleged exceptionality have not been convincing and either way would not be sufficient reason to modify the established practice in these bodies. The established practice is intended to ensure timely decision-making and to prevent a minority of states from obstructing progress by wielding veto power.

- Restrict the participation of other stakeholders and limit their meaningful contributions to the process. At the first meeting of this negotiating session there was an incident that involved a lengthy discussion over Turkey’s objection to the accreditation of three civil society organisations. Fortunately, member states did not accept this objection and all organisations were accredited. A few days later, and less restrictive in nature, France requested that civil society organisations be heard only after all member states had spoken, if time allows. Although these are two very different actions, the two episodes reinforce the importance of all member states being on the same page in terms of valuing the opportunity that the UN rules of procedure offer to deliberate in a more informed manner with the input that civil society and other actors can bring to the process. The limited and precious time the Committee has for fulfilling its mandate should focus on using the input of all actors to jointly achieve the best outcome rather than on time-consuming discussions to restrict the existing participation mechanisms.

These tactics, coupled with silence as a strategy by the countries who voted against the resolution last year — which made the meetings particularly short during the last week of negotiations — led countries such as Nigeria to argue in its closing remarks on 8 May that good faith in negotiation must not only be preached but put into practice by all countries.

Country blocs around the main procedural and substantive discussions

Acknowledging the nature of the Ad Hoc Committee’s mandate by all countries should facilitate the task ahead: finalising the terms of reference in the indicated timeframe. What is the balance after the first session and what can we expect from the discussions to come?

The following analysis is based on two tools that the Tax Justice Network has made available to the public to monitor the negotiations: 1) a database on who wants what from the UN tax convention negotiations; and 2) the transcripts of the sessions, which allow for a detailed reconstruction of the dynamics of the ongoing negotiations.

Different views on the type of framework convention, its objectives and principles

The first days of deliberations focused on more general issues on what kind of parameters the terms of reference should set. That discussion showed stark differences in the type of framework convention that states are advocating for and varied views on what its general provisions should be. These different views of the type of convention desired, and on what the objectives of the framework convention should be, were also evident in the widely varying proposals countries submitted in writing ahead of the session.

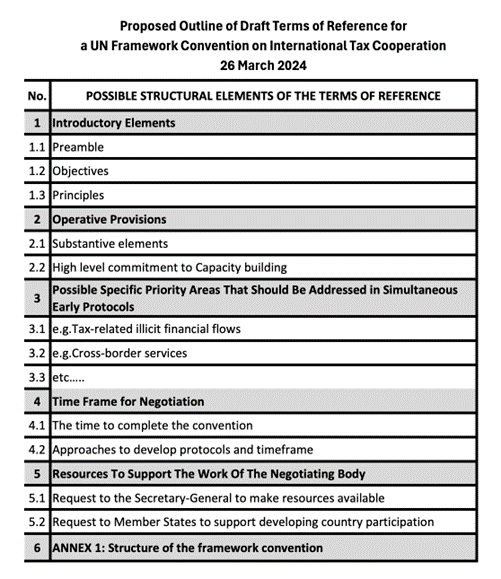

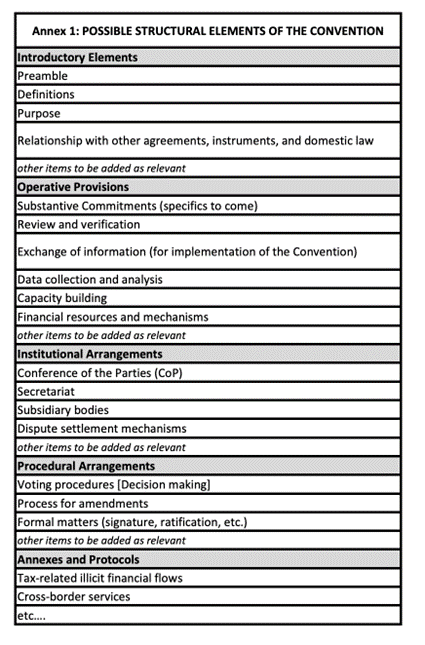

During the session, the positions on the type of parameters that the terms of reference should set were divided into two main blocs. A first group of countries – mainly those that voted against the resolution adopted last year – argued that the terms of reference should give very general guidelines and focus on the procedural aspects for drafting the framework convention – without prematurely addressing anything that could prejudge its content. A second group comprised of global south countries showed stronger support for an initial outline for the terms of reference and for an annex with the possible structural elements of the framework convention, both prepared by the Ad Hoc Committee’s Secretariat based on the inputs States submitted to the process (see images below). They later suggested the terms of reference should have a broad-based approach according to which all issues should be up for discussion, and that the terms of reference should include some substantive scoping along the lines of the draft outline of the elements of the framework convention proposed by the Secretariat.

Despite differences over the emphasis that the terms of reference should have, states adopted a working agenda that over several days addressed an exploration of substantive points that could be included as high-level commitments of the framework convention.

The issues that countries want the framework convention to address

The exploration of the issues identified an expanded but not exhaustive list of issues that the terms of reference should contain as a guide for the negotiation of the framework convention. States expressed different positions on the inclusion of these issues. Richer OECD countries, including several vocal EU countries, noted that the framework convention should focus on less controversial issues and not duplicate efforts with other fora (implicitly and at times explicitly, the OECD). Global South countries (including some OECD members) generally argued for the need to include all relevant issues, even if they had been addressed by other fora. It is the Tax Justice Network’s view that in order to incorporate the perspectives of all countries, an inclusive framework convention on tax should not exclude any of the issues discussed, and particularly those that lower-income states consider to be priorities.

Before reviewing states’ positions on specific issues, two more cross-cutting observations should be made. The first is about the language used. While states use similar terms such as “domestic resource mobilisation”, “capacity building” or talk about their commitments to “fully inclusive and more effective tax cooperation”, the scope of these terms can be very different. For example, for Global South countries it is key that domestic resource mobilisation is understood to include combating illicit financial flows, while for richer countries it is often associated with a capacity building agenda to enforce existing standards and improve the collection of specific taxes in lower income countries.

To resolve these differences, we believe it is necessary to build on the most comprehensive definitions adopted in the most universally accepted fora. This can help overcome discussions in which states should avoid becoming embroiled. For example, in the discussion on the issues that should be addressed as part of the simultaneous development of early protocols, the United States raised that the term “tax-related illicit financial flows” was ambiguous, and noted its concern that certain tax avoidance practices might not be considered illegal in certain countries and as such should not fall under that definition. This objection was raised despite the fact that UN’s formal statistical definition already includes cross border tax abuse by both multinational companies, through profit shifting, and wealthy individuals hiding assets and income streams offshore whether illegal or not. Considering such established definitions, therefore, there should be no doubt as to the extent to which some terms should be interpreted. Furthermore, the whole purpose of covering “tax-related illicit financial flows” is to develop rules that are less prone to aggressive tax avoidance to the detriment of global south countries. As such, whether these practices are legal in the United States or in other high-income countries, is irrelevant.

A second observation has to do with the information used for resolving controversies in the negotiations. If one starts from different premises or a different diagnosis of the problems of the current tax architecture, states may entrench themselves in rhetorical positions that do not address what other countries are calling for. For example, African Group countries have insisted that there are structural problems with the standards decided in other fora such as the OECD because these standards fail to consider the realities of African countries and because they were decided in a forum without meaningful and equal participation — facts on which ample evidence can be provided. In contrast, richer countries, and in particular OECD countries, repeatedly cite the risks of duplicating what already exists, including these problematic standards, thereby ignoring objections to the legitimacy and effectiveness of existing instruments without providing any evidence base to address the concerns of other countries. The search for a common understanding implies approaching the process in a way that genuinely addresses the concerns of other parties.

With these two observations shared, we now provide summaries of the positions that were expressed on specific issues.

Domestic resource mobilisation and capacity building

A first discussion was on the scope of the concept of domestic resource mobilisation (DRM). In written submissions the term was mostly used by countries from the global north, as the following table shows.

During the sessions, there were two main positions on this issue (see statements on the matter here). A first group of countries argued that domestic resource mobilisation should be the priority issue to be addressed by the framework convention, with an emphasis on capacity building in lower income countries. A second group of countries pointed out that domestic resource mobilisation must be understood beyond capacity building measures and include issues of fair allocation of taxing rights and progressivity of tax systems. Hence, according to the second group, domestic resource mobilisation and capacity building should be addressed separately (recognising the importance of capacity building under an approach that addresses the needs of Global South countries). The chart below summarises how positions were aligned during the session.

The Chair concluded this agenda item by acknowledging that domestic resource mobilisation would need to be understood as having at least two components: one related to capacity building and the other including fair allocation of taxing rights and broader issues.

Effective taxation of high-net-worth individuals, including wealth taxation

Several states raised demands in their written submissions in relation to the inclusion of taxation of high-net-worth individuals, as shown in the table below.

During the session, there was a broad agreement on the importance of this issue for combating inequality and achieving other aims, but positions on how to include it in the framework convention varied. On the one hand, Brazil stressed that it considered this to be a crucial issue, for which it had made a proposal in the context of the country’s G-20 presidency. Brazil pointed out that the United Nations would be the most inclusive forum to discuss this issue. Spain and France indicated their support for Brazil’s proposal to the G-20 and suggested that the modalities for inclusion in the framework convention could be defined at a later stage. Colombia, Morocco, Belgium and Austria were more in favour of referring to the taxation of very high-net-worth individuals as a high-level commitment under the framework convention.

A second bloc of countries noted that the taxation of wealth was an issue of domestic tax policy to be decided by each country individually. But these countries were still open to considering options for including it as a high-level commitment, although some more open than others. These countries insisted on the need for a flexible approach that recognises the diverse circumstances of each country. Interventions from Japan, Canada, China, Germany and Sweden fell within this view. The United States, the United Kingdom and Korea more strongly emphasised that this was a domestic taxation issue and were more sceptical about its inclusion in the framework convention. However, they did not raise insurmountable objections in principle, and Korea and the United Kingdom indicated that they were open to considering it. Mauritius and the Bahamas raised some technical doubts about design of wealth taxes and how to include it in the framework convention.

A third bloc argued that the issue was indeed very important but suggested including it either under the high-level commitment on domestic resource mobilisation (Nigeria, Jamaica, Singapore, Chile), the high-level commitment on combating illicit financial flows (India, Kenya) or under a new high-level commitment on combating inequalities (Japan).

Given that there was broad consensus on the importance of the issue, the Chair noted it should be included in the negotiation, although the specific modalities would have to be defined at a later stage.

Making sure tax measures contribute to addressing environmental challenges

On this issue, there was broad agreement on its importance and urgency and no objections to its inclusion were heard from any member state (except a call for caution from Korea).

There were different emphases on the measures that could be considered. Argentina, India, Mauritius, Bahamas and Kenya highlighted the principle of shared but differentiated responsibilities. The latter two argued that careful consideration should be given to the way this issue is addressed with a view to avoid restricting lower income countries’ policy space to exploit their natural resources.

Singapore, South Africa and Kenya focused more on the issue of carbon taxes, while Japan, France and Sri Lanka spoke of a wider range of instruments. Colombia raised the issue in connection with the need to mobilise more resources and fill the climate finance gap.

Spain, Norway, Austria, Italy and France spoke about the importance of the issue, and France mentioned the joint initiative they launched with Kenya on the Taskforce on International Taxation and Climate as a benchmark that could help the UN to give greater political relevance to this issue.

Equitable taxation of multinational corporations

One of the most controversial moments of the first round of negotiations occurred on the morning of 1 May. The agenda item to be addressed was the inclusion of the issue of equitable taxation of multinational corporations as a high-level commitment. The positions of the countries were divided into two blocs. A minority bloc expressed concern that the inclusion of this issue would erode the progress made in other fora, and particularly regarding the two-pillar agenda of the OECD’s Inclusive Framework. They insisted on the alleged risks of “duplication” and argued that any discussion of these issues would have to be consistent with ongoing work in the OECD framework.

A second bloc, representing a majority of countries, advocated for comprehensive inclusion of the issue as part of the high-level commitments. Within this group, some pointed out that a forum such as the OECD’s Inclusive Framework could be considered neither transparent, nor equitable, nor inclusive, and as such it was a distortion to say that all countries had already reached agreement in this area in reference to the two-pillar agenda. The expression “140 is not 193”, referring to the number of jurisdictions that are part of the Inclusive Framework as opposed to the number of UN Member States, was heard on several occasions. They also pointed out that the Inclusive Framework was hardly a forum in which its member states could participate on an equal footing. It was also raised that the risk of fragmentation would arise from not including this issue as part of the framework convention on tax. Other states argued that including this issue would not lead to the erosion of work already done in this area but rather consolidate that work.

In his closing remarks on this agenda item, the Chair acknowledged that there are different views on the matter. He acknowledged that a group of countries were concerned with duplication but as this concern connected more with how the work would be done rather than about whether it should be added or not, he concluded the corporate taxation issues will be included to be discussed as high-level commitment in the terms of reference.

Additional topics that can be included as high-level commitments

As part of the agenda, member states suggested additional issues to include as high-level commitments in the terms of reference. These included:

- Indirect taxation to contribute to domestic resource mobilisation

- Institutional capacity of revenue administration

- Assistance in revenue collection

- Country by country reporting (the Tax Justice Network intervened on this matter)

- Taxation of extractive industries

- High-level commitment on fairness

- Dispute prevention and resolution mechanisms (a presentation by the Secretariat was made on this)

- Certainty, equality and predictability as high-level commitments.

- Eradicate economic imbalances between nations

The Tax Justice Network proposed the inclusion of measures related to the ABC of tax transparency, including the proposal to create a Global Assets Register and a Centre for Monitoring Taxing Rights.

Procedural aspects

Development of simultaneous early protocols

The UN Secretary-General’s report to the General Assembly in 2023 noted that:

“Protocols to the framework convention could provide additional, “regulatory” aspects, with more detailed commitments on particular topics, giving countries the ability to opt-in and opt-out on the basis of their priorities and capacities. If there is sufficient agreement on certain action items, some of these protocols could be negotiated at the same time as the framework convention. This might include, for example, a protocol on measures to address the problem of illicit financial flows”.

In addition, Resolution 78/230 required the intergovernmental committee, in elaborating the draft terms of reference for a framework convention “to consider simultaneously developing early protocols, while elaborating the framework convention, on specific priority issues, such as measures against tax – related illicit financial flows and the taxation of income derived from the provision of cross-border services in an increasingly digitalized and globalized economy”.

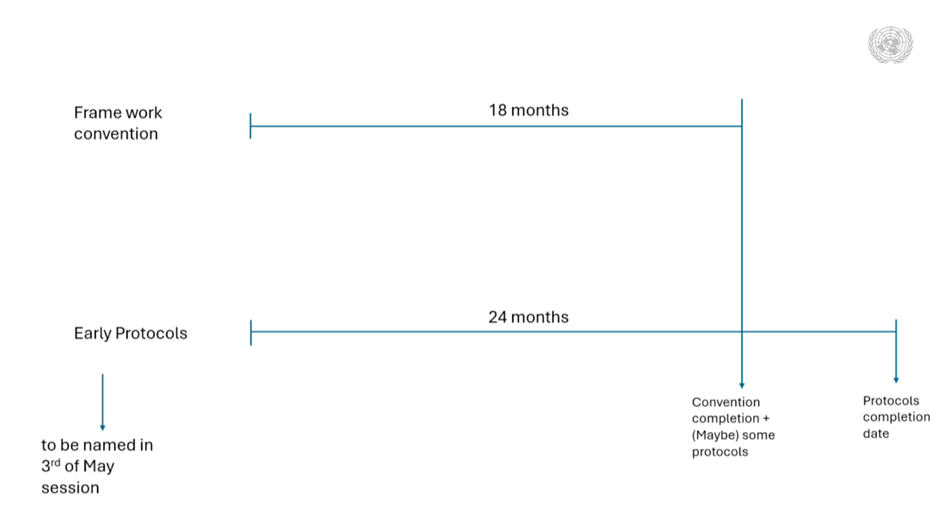

With this framework for discussion, negotiations on the 2nd and 3rd of May focused on addressing the issue of the simultaneous development of early protocols to the negotiation of the framework convention. Countries came to the session with various proposals on the issue of protocols in their written submissions. During the session on 2 May, two main blocs emerged. A first bloc proposed a sequential approach: first the framework convention, then protocols. A second bloc proposed to develop simultaneous protocols on urgent issues to respond to the needs of member states, even if they were controversial. An intermediate proposal came from the United Kingdom delegation to combine simultaneous and sequential work. The Chair summarised the proposal with the chart below.

This was followed by a discussion on the ambition of the proposed timeline, in which the African Union, India, Chile, China and others raised their support for the proposed approach, while other countries such as Sweden, Germany and Austria raised that there were still too many unknowns to make an informed decision. Argentina, Switzerland and the United Arab Emirates raised doubts as to whether simultaneity was feasible in terms of the resources that needed to be allocated. The conversation on the proposed timeline was followed by a presentation by the Secretariat on dispute prevention and resolution that some countries welcomed for providing clarity in terms of how the Framework-Protocol approach might operate.

On 3 May, the session started with a discussion of possible issues that early simultaneous protocols could address. Global south countries led with strong interventions aligned on the need to have simultaneous early protocols, with some range of issues discussed, but mainly mentioning the topics of tax-related illicit financial flows, information exchange, and taxation of cross-border services. There was some noteworthy pickup of civil society demands. For instance, India called for progress in tackling illicit financial flows by means of beneficial ownership and legal ownership registration, and Brazil suggested considering public country by country reporting.

This was countered by many OECD countries with a strong pushback against simultaneous early protocols, justified by resource constraints for parallel negotiations and the resulting need to prioritise, and by the desire to better understand how the framework convention would work and how everything would fit together,etc. In this context, controversies emerged over the understanding of some terms, including the definition of illicit financial flows.

The US took the floor and poured a bucket of cold water on the negotiations, speaking directly against three of the most frequently mentioned issues for consideration for early simultaneous protocols: tax-related illicit financial flows, information exchange and the taxation of cross-border services. The US specified that the term illicit financial flows should be interpreted to apply to criminal proceeds not only from tax crimes, but also from corruption and organised crime, and remove from scope tax avoidance which may not be illegal but “lawful” (here is why we beg to differ).

On exchange of information, the US expressed concerns that the existing international standard may be duplicated, in conflict with or eroded by any action by the UN framework convention on international tax cooperation in this area. Specifically, the US defended the standard of “foreseeable relevance” of requested information, which is the threshold for a country to exchange tax information under bilateral tax treaties and the Convention on Administrative Assistance in Tax Matters. It’s worth keeping in mind here, however, that neither the overwhelming majority of UN members nor the overwhelming majority of Global Forum members had any say in designing this standard. The standard has proven to be very cumbersome to adhere to in lower income countries, drastically reducing the effectiveness of the whole exchange of information regime in the global south.

Since the US does not participate many of the international standards it tries to defend (e.g. the US has not signed the Amended Convention on Administrative Assistance on Tax Matters; it also does not participate in the automatic exchange of financial account information under the Common Reporting Standard for Automatic Information Exchange; and often the country fails to live up to promised reciprocity under its own system of obtaining foreign account information, known as ‘FATCA’.), the US’ statement is a remarkable feat in hypocrisy.

With the US not walking the talk on tax information exchange, and oblivious to the democratic deficit in bringing about a standard for information exchange that is largely ineffective especially for lower income countries (as Tax Justice Network has explained in this briefing), designing better rules on global exchange of information can hardly be seen as an erosion of current standards. The ineffectiveness of the current standards was highlighted by Senegal by mentioning and acknowledging that information exchange is already happening, yet then emphasising how it would need to be improved for it to work for Senegal and similarly situated countries. Requests for information exchange would for example often not be answered, so at the UN, there should be a binding obligation to respond to requests with the requested data or with a valid reason why the data was not obtainable.

The discussion continued between a bloc of Global South countries arguing for the urgency of early action and prioritising the most pressing issues for resource mobilisation, and a group of higher income countries continuing to argue for the desirability of the sequential approach and the need for further analysis. Korea and Norway suggested that a Commission of International Organisations working on the Platform for collaboration be invited to provide further analysis on specific issues. Nigeria, on behalf of the African Union, made a compelling case to explain that existing rules are not catering to the needs of all countries and, therefore, urgent action is required in key areas that early protocols should address for mobilising resources to tackle poverty and other pressing challenges.

The final meeting of the first week closed with a recap by the Chair on the issues raised by delegations as priority issues for the development of early simultaneous protocols:

- Cross-border services

- Illicit financial flows

- Digital economy

- Dispute resolution

- Taxation of high-net-worth individuals

- Environmental and climate challenges

- Exchange of information

- Tax incentives

In line with the joint submission of the Global Alliance for Tax Justice and the CSO Financing for Development Mechanism that the Tax Justice Network endorsed, we believe that any elements to be developed by protocols should be covered by strong provisions in the negotiation of the framework convention itself. In our own written submission, and in line with what has been raised by several countries in the global south, the Tax Justice Network believes that an early protocol on illicit financial flows should be part of the list of protocols to be prioritised, incorporating the ABC of tax transparency – i.e. automatic exchange of information, beneficial ownership transparency and (public) country by country reporting – and the creation of a Centre for Monitoring Taxing Rights. Whether negotiated simultaneously with the framework convention or under other arrangements, these elements, as well as others that countries may wish to develop further through protocols, should be included as part of the core content of the framework convention. Capacity issues need to be carefully considered by countries in a simultaneous negotiation of early protocols from a strategic standpoint, but far from being a zero-sum game many of the bottlenecks in the more general discussions could be resolved by parallel technical negotiations on more specific issues that early protocols can address.

Roadmap for second session, preparatory work and timeline

The second week of negotiations proceeded at a slower pace, with several countries refusing to make additional interventions on substantive or procedural issues in the absence of a zero draft that captured the earlier discussions. In this context, the final days focused on reaching agreement on the way forward, as summarised in the timeline below (prepared by our partners at the Center for Economic and Social Rights).

This ambitious roadmap implies several challenges for the different actors involved in the process. For UN member states, it will involve preparations for the decisive negotiations between July and August, which given the events of the first session are expected to be very tough and complex. For countries in the global south, the stakes are measured in terms of the resources that states lose every day to respond to the climate and other interrelated crises, and to build schools, hospitals, sustainable infrastructure and to mobilise the resources with which the realisation of people’s rights can be financed. For high-income countries that until now have been in the driver seat of global tax governance, it is a simple matter of accepting that international tax norms need global support, a fair distribution of benefits and a special reckoning of the needs, priorities and capacities of global south countries. But also, a matter of recognising that universally accepted rules that correct the flaws in the current tax architecture are beneficial for all countries. Such highly needed rules might contribute to put an end to the astronomic losses that richer countries suffer from tax abuses to the detriment of their own population (which are greater in absolute terms than those of lower income countries).

Achieving a shared understanding to focus everyone’s energies on agreeing terms of reference that enable the negotiation of an ambitious convention is critical for the process. However, discussions are tough, and the negotiation issues are sensitive. Continued leadership, unity and perseverance by Global South countries – the kind that brought us to these negotiations in the first place – will be required to see this process out in a successful way.

Evidently, it will be a major challenge for countries to achieve a successful negotiation in the short time ahead. For other stakeholders involved, ranging from the Secretariat facilitating the discussions to civil society observing the process, it will therefore be key to assist countries in drawing the right conclusions to make consensus achievable. As such, the Tax Justice Network will continue to provide tools and analysis to support the negotiations, and to collaborate with partners within the tax justice movement and beyond so that the world seizes this historic opportunity for change.

Related articles

Disservicing the South: ICC report on Article 12AA and its various flaws

11 February 2026

What Kwame Nkrumah knew about profit shifting

The last chance

2 February 2026

After Nairobi and ahead of New York: Updates to our UN Tax Convention resources and our database of positions

The tax justice stories that defined 2025

2025: The year tax justice became part of the world’s problem-solving infrastructure

Bled dry: The gendered impact of tax abuse, illicit financial flows and debt in Africa

Bled Dry: How tax abuse, illicit financial flows and debt affect women and girls in Africa

9 December 2025

Two negotiations, one crisis: COP30 and the UN tax convention must finally speak to each other