Carolina Rodrigues Finette ■ As a former schoolteacher, our students need us to fight for tax justice

One of the first questions I was asked when I joined the Tax Justice Network was “how did a former schoolteacher come to be involved in the tax justice movement, and why?”

If you’re an educator reading this blog, there’s a decent chance you might be asking yourself “what even is tax justice?”

I was born and raised in Brazil. At the age of 18 I became a history teacher at a public school in the countryside, as part of an internship program my university had with the local schools. My first students were around fourteen or fifteen years old (not much younger than me). My plan had been to stay with the program for the four years it would take me to graduate, giving me enough experience to run my own classroom after graduation.

And it probably would have been the case, if it weren’t for the fact that this internship turned out to be a full-time job. The school (like many others in the district) did not have the funds to hire new staff and used interns as full-time employees. Back then, I had no teaching experience. Although I knew this was not what the program was supposed to be, I really needed the scholarship to stay in college.

I ended up teaching for about a year without a full-time salary, and with no rights as an employee. I finally moved to another school, where I at least had a teacher to guide me. Besides having unprepared and poorly paid interns as teachers, both schools faced many other issues – large numbers of students per classroom (mine had around 45), dilapidated buildings, lack of books and school supplies, lack of hygiene items, poor food quality and much more.

In my experience, both students and teachers are greatly impacted by our schools’ challenging conditions. It is disheartening to see students have their right to education continuously neglected. Watching so much enthusiasm and potential not being explored to the fullest due to the lack of resources. On the other hand, teachers are facing immense challenges, too. The profession is getting more precarious, with teachers often having to work with limited resources and funding. It’s very hard for them to provide the best learning environment when they themselves are dealing with so many uncertainties. Both students and teachers deserve better support, resources, and recognition for the vital roles they play in shaping our future.

This experience sparked my curiosity to understand how schools get to this point, and what different aspects play a role in this – privatisation processes, unattractive career plans, corruption, etc. One thing was clear: all these issues were intrinsically connected to funding (or rather the lack of it).

When it comes to education funding in most Global South countries, there’s a lot in the media about external aid. Much is said about the massive loans made to governments by the World Bank and other international institutions, and how these can supposedly play a positive role in transforming education. But these only represent around 3 per cent of the funding allocated to public education worldwide, while the other 97 per cent comes from domestic sources. So, shouldn’t we be paying far more attention to the latter instead?

When we talk about “domestic sources”, we are mainly talking about tax revenue. This is the income collected by governments through taxation, which is used to sustain public services, infrastructure and administration.

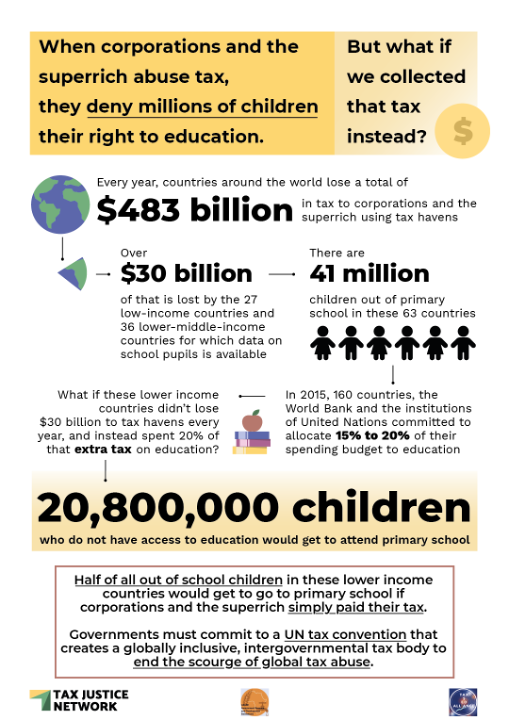

Despite the importance of tax revenues, lower-income countries lose more money in unpaid tax revenues every year than they receive in international aid.

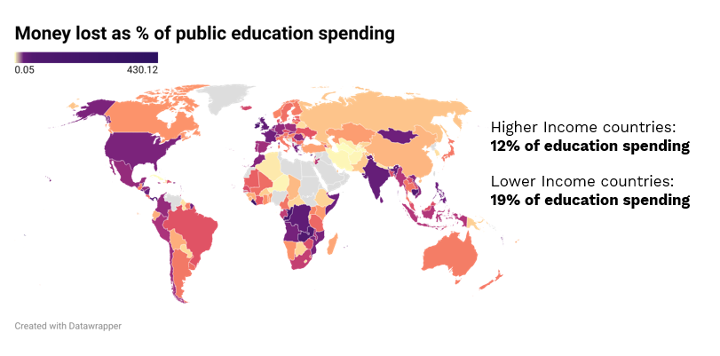

This has made it easy to explain why I ended up working with taxes: I joined the tax justice movement because tax abuse is costing us our right to education. Our right to free, public, quality education for all. When wealthy individuals and corporations don’t pay the fair share of tax they owe to society, we lose very necessary funds that could be allocated towards our students and schools – to be more exact, around 19 per cent of it in lower-income countries annually↪NOTETo calculate the percentage of public education spending lost, we compared education spending in each country (in terms of GDP ration and in US$, retrieved from the World Bank data) to the amount of money lost to tax abuse in each country (retrieved from the State of Tax Justice 2023 report).. As a result, almost 21 million children are denied a place in primary school every year – just because there isn’t enough money.

On top of that, corporations and wealthy individuals continue to create philanthropies to “support” education. Of course, these often end up instead being a source of indirect profits, political power and positive visibility for them. They appear to have misunderstood their purpose. As Hector Ulloa (a steering committee member of the Global Student Movement) so aptly said, “As business corporations, their role isn’t to run philanthropic education initiatives, but rather to fully pay their taxes so governments can sustain our right to public education” in a democratic and sustainable way.

This World Education Day is a reminder of the vital importance of public education. When it is managed and delivered publicly, with adequate funding, and in the public interest, it is the most effective way to build just, inclusive, and sustainable societies. It is a powerful tool for diminishing inequalities, repairing colonial legacies, and meeting sustainable development goals and human rights commitments. The principles of tax justice can ensure that our governments have enough funding to guarantee the delivery of this right with ample funds and in a democratic manner by liberating this process from the constraints of aid and the private interests of donors.

At the Tax Justice Network, we work every day to make sure that tax systems are able to provide funding for fundamental human rights. Our work with the TaxEd Alliance is aimed at urging a radical reframing of the way in which the right to education is financed. To do so requires the adoption of the principles of tax justice, where everyone pays their fair share.

Together with partners (such as the ActionAid, the Global Campaign for Education, the Global Initiative for Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, the Centre for Economic and Social Rights and regional partners), we will continue to advocate for just tax practices, and the right to free, quality education that flows from it.

Related articles

One-page policy briefs: ABC policy reforms and human rights in the UN tax convention

Tax justice pays dividends – fair corporate taxation grows jobs, shrinks inequality

The millionaire exodus myth

10 June 2025

Lessons from Australia: Let the sunshine in!

UN Submission: A Roadmap for Eradicating Poverty Beyond Growth

A human rights economy: what it is and why we need it

Do it like a tax haven: deny 24,000 children an education to send 2 to school

Incorporate Gender-Transformative Provisions into the UN Tax Convention

The international tax consequences of President Trump

27 February 2025

Just Transition and Human Rights: Response to the call for input by the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights

13 January 2025