Andres Knobel ■ How to stop #LuxLetters and the abuse of tax rulings

Written by Leyla Ates, Andres Knobel, and Markus Meinzer.

One of the most powerful tactics a multinational corporation can use to abuse tax is to secure a tax ruling in one country that gives the corporation written permission to exercise an abusive interpretation of the country’s tax law in a way that ultimately enables the multinational corporation to underpay tax in other countries where it operates. While in recent years countries have started privately exchanging or publishing some information on the tax rulings they issue to multinational corporations, these partial disclosures are not enough to stop the use of tax rulings for corporate tax abuse. Even if the full text of tax rulings were disclosed, it can still be impossible to understand how much corporate tax is being underpaid.

We propose here a number of measures to address this. In summary, each ruling should:

1. Be published online

2. Identify the legal person(s) involved and their tax advisers

3. Include the multinational’ country by country reporting data

4. Include a description of the full tax scheme, including any other rulings or schemes involved

5. Include an assessment of the tax impact

States should also commit to:

6. Protect and reward whistleblowers who reveal undisclosed tax rulings

7. Allow anyone to challenge the validity of a ruling

Tax rulings as tools for tax abuse

In essence, tax rulings are resolutions by a tax administration that give some level of certainty to taxpayers about how the tax administration interprets a specific regulation or transaction. Usually, a tax ruling on its own isn’t enough to enable tax abuse, but it can be a crucial part of a larger tax abuse scheme. When used constructively, tax rulings may help taxpayers understand and properly apply an ambiguous regulation, saving both taxpayers and the tax administration time and resources. However, over past decades tax rulings have increasingly been used as powerful tools for tax abuse. This is especially the case with “unilateral cross-border tax rulings”, where the tax administration of one country “unilaterally” issues a tax ruling that will have effects on the tax obligations of a taxpayer, such as a multinational corporation, in many countries. Due to the international or “cross-border” nature either of the taxpayer (eg a multinational corporation operating in several countries) or the transactions (eg interest payments on a loan a multinational corporation lent itself from a subsidiary in one country to a subsidiary in another country), a unilateral cross-border tax ruling can give a multinational corporation legal cover in one country to undermine the rule of law in other countries.

Abusive tax rulings can sometimes be unintentional consequences of a lack of capacity in a tax administration to understand the effects of a ruling, or of recklessness and corruption in a tax administration. At other times, abusive tax rulings can be part of a tax haven’s wider, deliberate efforts to attract multinational corporations by enabling them to reduce their tax liabilities in other countries.

In these latter cases, abusive tax rulings are utilised alongside other abusive mechanisms with the misguided intention of generating service fees and local spending from accountants and other professionals involved in the facilitation of global tax abuse. In reality, this strategy has been repeatedly seen to fail to generate sustainable, local economic development. Where more economically successful, it tends instead to impose a “finance curse”, a well-documented phenomenon where an oversized financial sector begins to extract wealth from other sectors of the economy, driving inequalities and ultimately shrinking the country’s overall economy. Aside from the economic consequences, hosting global tax abuse and an oversized financial sector can also be detrimental to democratic processes, public services and safeguards against corruption. Politically, the responsibility for the ruling practice lies in most cases with Ministries of Finance and their elected politicians overseeing the tax administration.

A bit of history

It’s likely that most people had never heard of tax rulings before the LuxLeaks scandal in 2014, which exposed secretive tax rulings issued by Luxembourg to ‘big four’ accounting firms in favour of some of the world’s most famous multinational corporations. In some cases, tax rulings in Luxembourg resulted in multinational corporations reducing their tax liabilities to less than 1 per cent of their (actual) corporate income instead of paying the statutory corporate income tax rate of then 26 per cent.

Even then, many people would still have found it difficult to fully understand what tax rulings are or what they are used for. Tax rulings come in different forms, shapes and names: unilateral cross-border tax ruling , informal tax ruling, information letter, unilateral advance pricing arrangements, advance pricing agreements (APA), capital ruling, etc.

In some cases, the ruling is legally binding, so once the tax administration issues or confirms it, the tax administration has to abide by it and can be sued over it. In other cases, the ruling isn’t formally binding but it may provide enough assurance that the tax administration will not challenge a tax return or assessment which complies with the non-binding ruling or with the information letter that has been discussed and shared.

Nonetheless, the damaging effects of abusive tax rulings are clear to see, which raises the question of how tax rulings are still justified today. The answer is that countries and international organisations such as the OECD, a club of rich countries and the world’s leading rule-setter on international tax, promote tax rulings because they bring so-called “tax certainty”.

Is there a need for “tax certainty”?

Tax certainty has become one of the key buzzwords in international tax in recent years that the OECD has made popular. Certainty is better than uncertainty, and surely tax is something you want to be certain about, so tax certainty must be a good thing, right? Tax certainty refers to the capacity to make an accurate assessment of the tax and compliance costs associated with an investment or transaction in a country. In other words, having tax certainty means if you’re setting up a company with a specific set of traits in a certain country, you can readily and confidently know how those traits will impact your tax obligations in that country.

On the surface, tax certainty can sound beneficial, if not essential. The OECD and the private sector speak of tax certainty as an ideal scenario that would make life easier for taxpayers and usher in prosperity for society as a whole. More certainty would lead to more investments, more jobs and more economic growth.

The problem, however, is that when the OECD and private sector are talking about tax certainty, they’re primarily talking about bringing clarity to a specific, loaded question: what is the lowest possible effective tax rate? When you seek to clarify what the lowest possible rate can be instead of what the actual statutory tax rate is, the uncertainty you face does not necessarily come from the letter of the law itself, as is often implied. Rather, the uncertainty stems from the convoluted, sometimes secretive interpretations pushed by tax professionals that distort the law beyond its originally intended – at times very obvious – meaning. This uncertainty is manufactured and sold as a service by accountants and tax advisors to multinational corporations and the super-rich seeking to underpay tax. Moreover, schemes deployed by accountants and tax advisors routinely cross the fine line towards illegality. In 2013, the UK’s Public Accounts Committee, a government watchdog, heard testimony from a senior official at a Big Four accountancy firm who asserted that his firm would sell a tax scheme to a client even if they reckoned there was only a 25 per cent chance the scheme would survive a court challenge.

What this means is that tax certainty is often about getting clarity not so much on what one’s tax obligations are, but on which loopholes one can exploit without getting into trouble for tax evasion.

Although tax certainty is often framed as a matter of making cumbersome state bureaucracy more streamlined and business-friendly, in reality it’s the industry of accountants and tax advisers, and the multinational corporations hiring them, that have made it incredibly difficult for tax authorities, legislatures and courts to keep up with and patch the loopholes manufactured to muddy states’ tax laws.

While tax laws tend to be overly complicated so that a lay person may indeed not understand much of it or what should happen in a specific case, multinationals and high net worth individuals usually hire big accounting firms and law firms who understand the law very well. In many cases, those big accounting firms and law firms may have been involved in writing some tax laws, whether through lobbying, as contractors paid by the state itself, or as part of a public consultation. In whichever case, there may well arise opportunities to understand or to insert loopholes in a country’s tax system, which paying clients can then be offered to exploit.

In contrast, the “uncertainty” usually starts in a (tax abusive) process called “risk mining”. Here, tax advisers deliberately have multinationals pay low taxes counting on the (low) probability of challenge from the tax administration. This may be due to the tax administration lacking the capacity to challenge all tax payments, or the political will to go to court without greater certainty of winning the case. To have a sense of how bad a company’s risk mining, or tax abuse in general may be, company directors could easily check how far removed their effective tax rates are from the statutory rates of the country (over a period of time, and taking into account the investment cycle etc). And the public may soon be able to do the same once public country by country reporting has been enacted. All countries publish their nominal tax rates. With the exception of some openly zero-rate jurisdictions, the nominal rates are usually high – even for some of the obvious corporate tax havens such as Luxembourg and the Netherlands. However, multinationals know that they are able to achieve much lower tax rates. That’s why the Corporate Tax Haven Index assesses the lowest available corporate income tax rate or LACIT faced by multinationals.

Low tax rate or secretive tax ruling?

Given that most countermeasures against tax havens focus on the statutory tax rate, countries may be unwilling to reduce much their statutory rates to prevent becoming an obvious tax haven. As Luxleaks showed, that is precisely what Luxembourg did, where the statutory corporate tax rate of 26 per cent was very far from the less than 1 per cent effective tax rate actually paid by some multinationals. (More happily, this is also why current proposals for a global minimum corporate tax rate focus on the putting a floor under the effective rate paid in each jurisdiction.)

Up until recently, tax rulings were confidential, so issuing abusive rulings was rather easy. Following the OECD Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) Action Points and the amendment to the EU Directive on Administrative Cooperation (known as DAC 3), countries are now supposed to exchange information on cross-border tax rulings with the countries where the rulings may have an impact.

As assessed by the Tax Justice Network’s Financial Secrecy Index and Corporate Tax Haven Index, most countries publish very little information on rulings. This information usually consists of just a summary of the ruling, which may be three pages long or just one sentence, without delving into detail. In most cases, published rulings are anonymised, so it’s impossible to know which multinational corporations or other legal entities are utilising the ruling to underpay tax.

However, lack of public access isn’t the only problem. Even countries’ tax authorities have trouble obtaining and understanding information exchanged with them on tax rulings. As reported by the European Court of Auditors:

“according to the visited Member States and to the Commission’s evaluation of the DAC [Directive on Administrative Cooperation], the summary of uploaded rulings sometimes lacked sufficient detail for a proper understanding of the underlying information; it was difficult for Member States to know when to request further information and, if they did so, to demonstrate that it was needed for purposes of tax assessment.”

Our indexes consider that tax rulings should be published online for free, should show the full text of the ruling and should name the legal person that requested it. But, is even this level of transparency enough to address the tax abuse risks posed by tax rulings?

If you can’t hide or run, you can confuse them

In a world where tax rulings (including informal ones) are supposed to be exchanged between countries, multinationals cannot rely on financial secrecy alone to hide their financial affairs. And given that almost 140 jurisdictions have committed to the BEPS Action Points and so are exercising some level of public tax transparency and exchanging information, running to a different country is hardly an option for multinational corporations seeking to keep their financial affairs beyond the reach of the law.

That leaves multinational corporations and their tax advisory firms with one last strategy: confuse authorities and the public about the meaning and consequences of tax rulings. One way to do this it for multinational corporations to secure tax rulings that are unintelligible to anybody without first-hand knowledge of the ruling’s origin and purpose. Another, even better, way is to secure tax rulings that look irrelevant or inoffensive so as not to raise any alarms to outsiders.

To understand how legal terms in a tax ruling may be completely misleading to outsiders, let’s use an example with a much more common legal instrument: a contract. Think of how lawyers write. If you ever purchased something online or hired a professional service, the contract you agreed to may have said something like, “Each Party will use its best efforts to take all actions and…”. Reading that might make you feel reassured. The seller is making a commitment to work hard and put in their best effort, that sounds great! Wrong! That’s just their way out. As long as the party proves that they did “their best”, based on some business practice or standard, then they are off the hook and don’t need to deliver.

This is precisely what happened between the EU and AstraZeneca when the company failed to deliver Covid-19 vaccines to the EU. As reported by Reuters, AstraZeneca chief executive Pascal Soriot “told newspapers on Tuesday the EU contract was based on a best-effort clause and did not commit the company to a specific timetable for deliveries”. Helpfully, these clauses work only when needed. This doesn’t mean that every time a “best effort” clause is included, the contractor will fail to deliver their services, but only that they could use this escape if needed.

What this all means is that the language of “best effort” in practice actually produces an outcome that is almost contradictory to the meaning of the language at face value. Rather than requiring the party to make an additional “extra” effort, the language of “best effort” allows the party to fail to deliver on its obligations without repercussion (based on having complied with some basic business standard). In this same way, the provisions of a tax ruling can produce an outcome wildly different from the meaning of their text at face value. Reading the full text of a tax ruling made public or exchanged with another country’s tax administration is one thing. Understanding the actual outcome of the tax ruling is something entirely different.

For instance, Luxleaks disclosed several secret tax rulings. Unfortunately, rulings don’t simply say, “let’s agree that you will pay 0.1 per cent in taxes”. In best cases, a tax ruling may say something like “therefore entity A, B and C (out of many entities mentioned in the scheme) will not be subject to withholding tax, and their interest expense will be deductible” or “pursuant to the hidden capital contribution treatment, interest waived to entity X will not be characterised as income but rather as capital increase and thus not subject to corporate income tax”. Although one could understand the meaning of each of these words and the sentences they form, it is almost impossible to understand how much tax the companies applying these provisions will end up paying or underpaying.

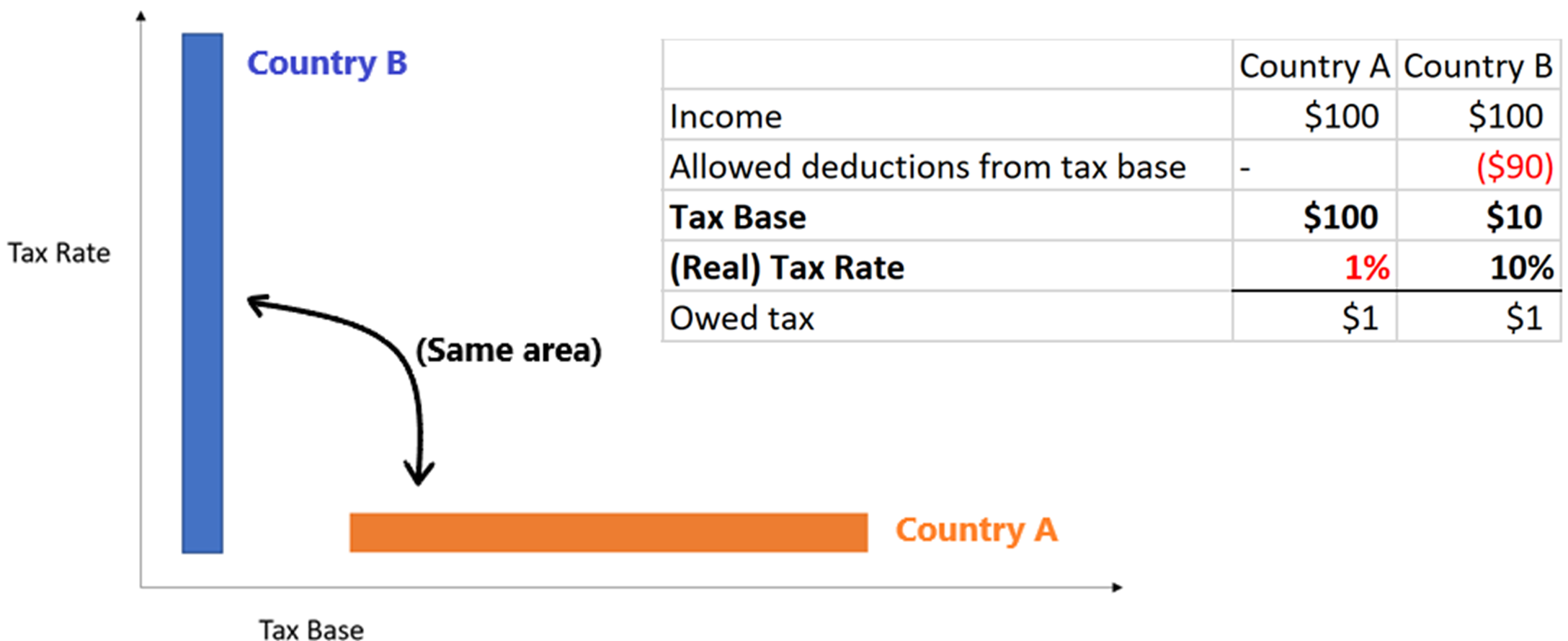

Tax rulings can also be much more complicated. Aside from determining which tax rates a legal entity can apply or be exempt from, tax rulings can also determine how much of its income is to be considered taxable – this is referred to as a legal entity’s tax base. For example, if a multinational corporation has a profit of $100, a tax ruling may determine that $80 of that profit is not part of the tax base – not subject to tax – due to some exemption. So even if the multinational corporation still pays a statutory corporate income tax rate of 35 per cent like everybody else, it will only pay $7 in corporate tax as only $20 of its profit are considered taxable at the tax rate of 35 per cent. That’s a far cry from the $35 the multinational would have paid if not for the tax ruling. In many cases, a tax ruling can both lower the tax rate and shrink the tax base, meaning tax could be underpaid even further.

The figure below shows how the same reduction in taxation can be achieved in two different countries where one country’s tax ruling manipulates just the tax rate and the other just the tax base.

Chart 1: The relationship between tax rate and tax base

Source: page 24, in: http://cthi.taxjustice.net/cthi2021/methodology.pdf

A need to zoom out

One of the key difficulties with understanding the impact of tax rulings is that often a tax ruling can serve as just one piece in a much wider tax abuse puzzle. While the impact of the tax ruling may not appear significant in the country where it was issued, it can enable damaging tax abuse in another country when it is used in combination with loopholes, tax treaties or other tax rulings in other countries. Even if a tax ruling is fully transparent, it may just refer to the tax liability of a specific transaction or the treatment of a specific type of income as either business income, dividend, interest or royalty.

Consider the following illustrative example (oversimplified, no, honestly, for the sake of clarity). A multinational obtains a tax ruling that classifies a payment as a royalty. This classification is then used to exploit a double tax treaty between two countries that exempts royalty payments from withholding taxes. Finally, the royalty payment received tax-free (no withholding taxes had applied) is not subject to corporate income tax either, based on the abuse of tax residency rules between two other countries.

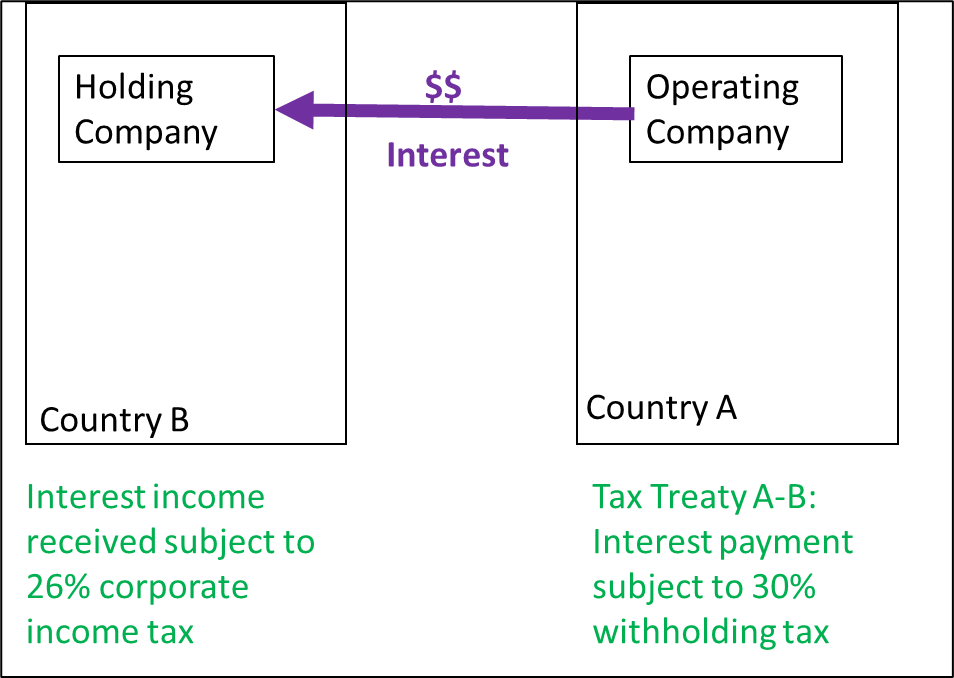

Chart 2 illustrates the example without any tax ruling or tax abuse scheme. A multinational with economic presence in countries A and B would have to pay withholding taxes to country A’s coffers on interest paid by its operating subsidiary in country A to a holding company in country B. In addition, the holding company in country B would pay corporate income tax for its interest income to the coffers of country B.

Chart 2: Taxation without abusive tax ruling

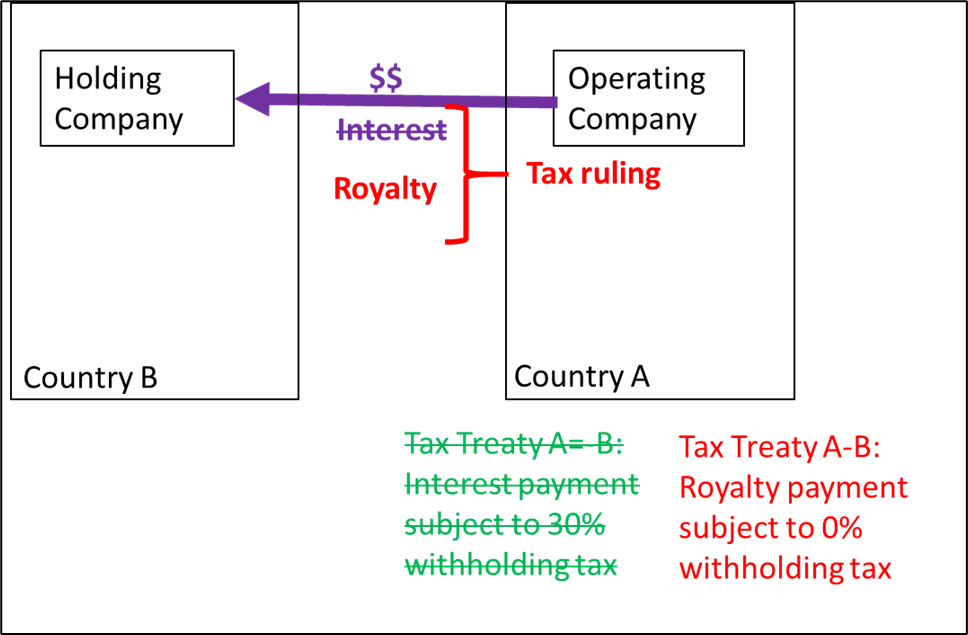

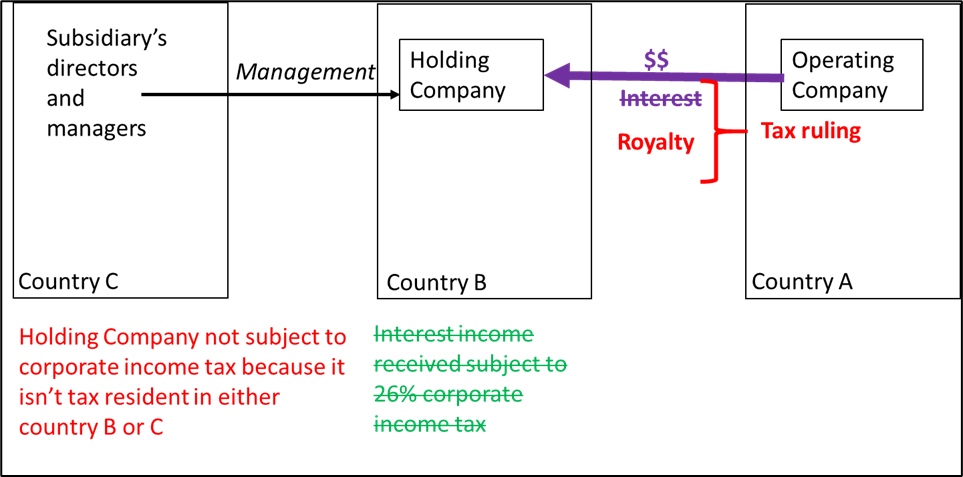

Chart 3 illustrates how the multinational company could use an abusive tax ruling to avoid the withholding tax of 30% in country A. First the multinational company and its advisers would analyse the tax treaty between country A and B. Let’s assume that this treaty exempts royalty payments of withholding tax in contrast to interest which is subject to 30% withholding tax. The tax advisers of the company could then attempt to reclassify the payments as royalties by entering into a tax ruling to that effect with country’s tax administration. The effect of such a ruling would be to eliminate 30% withholding taxes on the payment from country A to country B.

Chart 3: Eliminating the withholding tax in country A through a ruling

Second, the multinational would structure Country B’s operations to ensure it isn’t subject to tax (see chart 4). For instance, either through a tax ruling or directly by applying the local tax residency laws, it could incorporate the holding company in country B but have it managed in country C. Because Country B’s tax residence is based on place of management, while Country C’s tax residence is based on place of incorporation, the holding company would be considered non-resident for tax purposes both in countries B and C. In other words, it won’t be subject to tax anywhere.

Chart 4: Eliminating taxation at the level of the holding company

In other words, instead of the multinational company paying withholding taxes on the interest payment paid in country A plus corporate income tax rate in country B on the interest payment received, the multinational company would manage not to pay any taxes at all.

However, to understand the full scheme, it would be necessary to first become aware of the tax ruling, its details and to know which taxpayer it refers to. But as explained above, the ruling may also be convoluted. It may specify that this type of income, based on facts X and Y is to be subject to Article 10.3.b) of Z law. This will require an external party to understand what that article refers to. Moreover, even if the tax ruling will conclude in plain English that the payment is to be considered a royalty, that won’t say much to any other external party, eg a foreign authority. For that, they will need to know that a double tax treaty exists between the two countries, and that royalties aren’t subject to withholding taxes. Finally, the ruling, while crucial to make the whole scheme work, wouldn’t reveal the last part, where the interest/royalty income remains untaxed in Countries B and C based on the abuse of tax residency rules.

To make matters worse, instead of a formal tax ruling, the same effect may be achieved by an informal tax ruling such as an information letter where there is a non-binding document or an oral or tacit agreement whereby the tax administration commits in advance that it won’t challenge the fact that the multinational will treat the (purple) payment as a royalty.

Informal non-binding rulings could be structured in the very same way as a binding ruling, and could be agreed upon in the very same process as formal and binding rulings are agreed upon, involving closely held discussions between tax administration officials and senior staff tax advisers. The only difference could be that instead of calling it a “ruling”, another word is used, and that the binding signature is replaced by a more hidden and informal practice – such as an orally discussed and agreed approval process, that does not leave a paper trail to the administration, or remains in writing ambiguous as to the final position of the tax administration with additional oral assurances given.

Sounds like mafia to you? Spot on! Some of the Tax Justice Network’s senior advisers have long drawn parallels between global tax adviser firms and the mafia and have published about the pin-stripe mafia in law- and accounting firms. That is another reason why we propose a policy to address these risks, including by protecting and enticing whistleblowers from within these firms – a technique drawn from anti-mafia efforts.

Proposal

Cross-border tax rulings can be powerful and incredibly elusive tools for tax abuse. Even full public access to the text of tax rulings is not enough on its own to understand the role each tax ruling plays in global tax abuse and the scale of tax abuse it enables. For this reason, if countries are to continue issuing cross-border tax rulings, we propose that they must provide much more information alongside each cross-border tax ruling in order to make it easy to understand the effects of the tax ruling. We list the information that should accompany each cross-border tax ruling further below.

Given that no multinational is required by any country to obtain a tax ruling, but rather they seek them of their own accord or on advice by accounting or law firms in order to underpay tax with some level of safety from legal repercussion, a quid pro quo of transparency is entirely reasonable. Any cross-border tax ruling (either unilateral or bilateral, informal or formal, binding or non-binding) should be centrally deposited with an independent international body, such as a UN global tax body or a Centre for Monitoring Tax Rights, as was recently proposed by UN’s FACTI panel. This would make it possible for tax authorities as well as for journalists and civil society organisations around the world to check all the tax rulings a multinational corporation may be utilising and the countries issuing the most tax rulings.

We propose that every tax ruling should meet the following conditions. The information required by these conditions should be made available by the independent international body in a centralised database once it is established. Until then, this information should be made available by every country issuing a tax ruling. Each ruling (including ‘”information letters”, etc) should:

1) Be published online and for free in full text, within two weeks after approval or filing (no summary or redacted version).

2) Include the name and require a legal entity identifier of the legal person(s) addressed by the tax ruling, and of the accounting or law firm and any other tax professionals that advised on the ruling.

3) Include a full public country by country report for the multinational corporation(s) addressed by the tax ruling, ideally abiding by the GRI standard for country by country reporting.

4) Include a description of the full tax scheme utilised by the multinational corporation addressed by the tax ruling and into which the tax ruling fits. This can include all other tax rulings obtained by the multinational corporation in any country, and how the tax ruling interacts with tax treaties, residence rules and tax base calculation in other countries.

5) Include an economic and fiscal impact study, estimating the tax ruling’s impact on the tax base and tax rate applied to the multinational corporation. This would help exposes cases where the language of the tax ruling and the actual outcome of the tax ruling are contradictory.

In addition, governments including the authorities responsible for the tax ruling should:

6) Protect and reward whistleblowers who provide the media and public with evidence about any parallel system of practices that lead to bypassing official disclosure rules on tax rulings. In essence, whistleblowers who disclose information about abusive tax practices to either a local or foreign authority or to the public should not be subject to prosecution or criminal or economic sanctions. Instead, whistleblowers should be encouraged by rewarding them with a percentage of the tax revenues collected as a consequence of their disclosure, similar to what is practiced in the US.

7) Allow any user (civil society organisation or tax authority) to challenge the validity of the ruling, for instance if there is a supposition that the ruling isn’t as “inoffensive” as described by the multinational. (This is similar to Slovakia’s beneficial ownership register of entities engaging in public procurement, where any user may challenge the accuracy of the registered beneficial owner, and the burden of proof is shifted to the company). Alternatively, after the UN global tax body or Centre for Monitoring Tax Rights is established, the new body could be in charge of approving cross-border tax rulings if deemed non-abusive. In such case, the burden of proof would be on any user to prove that the ruling is indeed abusive.

It is worth noting that requirements 4 and 5 are far from radical. After all, the EU already obliges countries to require the disclosure of tax schemes by taxpayers and tax planners, and the OECD also published Mandatory Disclosure Rules on schemes that seek to avoid the common reporting standard for automatic exchange of information or to hide beneficial ownership.

A likely response to this proposal from multinational corporations is that tax rulings and the information required to meet the above conditions may be commercially sensitive information and so should not be disclosed. In principle, nothing enlisted above should be considered confidential, especially the name of the legal person addressed by the tax rulings. However, countries could establish a standard for determining whether information is too sensitive to disclose, similar to that used by some countries’ beneficial ownership registers. Just as public disclosure of beneficial owners may be limited in extraordinary circumstances where an authority confirms the danger in a specific case, an external authority could have the ability to redact commercially sensitive segments in extraordinary circumstances but not the name of the taxpayer or other details. Arguably, however, given that no multinational corporation is obliged to get a tax ruling, if a multinational corporation prefers not to disclose any of the above information, it should avoid obtaining tax rulings.

Conclusion

If tax rulings are to be issued, they should contain sufficient information to allow other countries’ tax authorities as well as any member of the public to easily and readily understand the implications of the tax ruling. It should not depend on understanding specific tax provisions or require an (often futile) investigation of other tax schemes exploited by the multinational. Seeing how multinational corporations, accounting firms and law firms have often been all too ready to abuse tax obligations and reporting rules, the protection and rewarding of whistleblowers on tax matters should become an international standard (as proposed recently by the UN’s FACTI panel in recommendation 7). This is vital to defend democracies and the rule of law worldwide.

Related articles

The “millionaire exodus” visualised

The millionaire exodus myth

10 June 2025

Did we really end offshore tax evasion?

The State of Tax Justice 2024

Submission to EU consultation on Anti-Tax Avoidance Directive (ATAD)

6 November 2024

How “greenlaundering” conceals the full scale of fossil fuel financing

Another EU court case is weaponising human rights against transparency and tax justice

Profit shifting by multinational corporations: Evidence from transaction-level data in Nigeria

5 June 2024

New Tax Justice Network podcast website launched!