Will Snell ■ How to supercharge overseas aid

Overseas aid is a “curate’s egg” – good, in parts. It can be a sticking plaster that merely patches over a global economic system that is structured to benefit richer countries and groups at the expense of the poor. It can be worse: last year, a group of concerned academics wrote an open letter to the World Bank, over its plans to expand the use of shadow banking techniques such as securitisation, derivatives and “repo” that underlay the global financial crisis – to attract more private finance into development. This could, they warned, usher in dangerous effects. These could include:

“permanent austerity along the lines of ‘privatizing gains, socializing losses’. More fundamentally, this seeks to re-engineer poor countries’ financial systems around capital markets”.

Used wisely, however, aid can help. If it acts as a catalyst to reform the underlying structural issues, then it can be especially effective.

One of the best (and most under-used) examples of using aid effectively for structural reform is investing in “domestic resource mobilisation” – techno-speak for countries building more effective and progressive tax systems.

Here are some killer facts.

- The US government found that increasing domestic tax revenues by 10 per cent led to increases of 17 per cent in public health spending in low-income countries, clearly undermining the idea that governments might not spend extra money wisely. Our own research suggests that greater reliance on tax revenues is associated not only with higher public health spending, but also with better coverage and outcomes.

- Oxfam produced an excellent report earlier this year, with a key suggestion to invest more aid money in tax systems. Oxfam’s research showed that a two percentage point increase in the domestic tax revenues of low and lower-middle income countries by 2020 would increase their collective annual budgets by $144bn, which is the same as the total amount of global aid in 2017.

- An international programme called Tax Inspectors Without Borders, which was originally a TJN idea, has estimated that every dollar invested has generated more than $100 in extra tax revenues.

There are promising signs. Twenty large donors have pledged to double their aid for domestic resource mobilisation between 2015 and 2020 through the Addis Tax Initiative. By next year, total global aid in support of tax systems should reach almost $450 million, though this is still well under 1 per cent of all aid. Even Bill Gates supports this, commenting at a recent United Nations financing event that “mobilising tax in developing countries is the most important source of finance for development.”

But how can donors best spend this money on helping low-income countries to raise more money through their tax systems?

Unfortunately, with some honourable exceptions, many donors that invest in tax systems go for the sticking-plaster approach – the uncontroversial, straightforward “quick wins” that promise easily measurable benefits. This means investing in what Oxfam describes as “narrow technocratic reforms”, mostly by providing “capacity-building” to help countries’ tax administrations and ministries of finance administer their tax systems more effectively. This is better than nothing, but there are two big problems with this approach.

First this does little to support countries in tackling the many barriers they face in making their tax systems more progressive. Many donor governments are still in the grip of a tired ‘tax consensus‘. As Oxfam points out, the barriers to effective reform include “excessive tax incentives for corporations and investors, a lack of taxes on wealth and assets (such as property and capital gains taxes), and failures of transparency, accountability and citizen trust in public institutions.” Countries need more help raising revenues in a progressive way, such as through direct rather than indirect taxes.

Second, Oxfam make the case for better “policy coherence” by donors. This means that rich countries (like the UK) should stop the two-faced practice of supporting low-income countries to improve their tax systems on the one hand, while undermining their ability to raise tax revenues on the other by, for example, blocking much-needed reforms to the global tax system.

So, a clear case of ‘do no harm’. But that’s not enough. As the Overseas Development Institute argue in a report published last week on civil society engagement in tax reform, donors should support a broader tax ecosystem, including civil society tax approaches that are politically savvy as well as technical.

We’ll bang our own drum for a second here. TJN was the pioneer in calling for automatic exchange of information across borders, as a tool to tackle tax evasion and other ills. We were laughed at, dismissed as utopians, and told that “this will never happen.” On a shoestring budget in our early years we pushed and pushed this idea. Now, a recent IMF article (written by a TJNer) summarises the result of the OECD’s ensuing global project on automatic information exchange:

The OECD estimated in July 2019 that 90 countries had shared information on 47 million accounts worth €4.9 trillion; that bank deposits in tax havens had been reduced by 20 to 25 percent; and that voluntary disclosures ahead of implementation had generated €95 billion in additional tax revenue for members of the OECD and the Group of 20, which includes major emerging market economies.

Now there is no way we can claim credit for all of this. But we can claim some. And there’s a lot more where that came from.

So we can make a double argument to donors: by curbing tax evasion and other assorted ills, we are not just helping low-income countries, but we are boosting the donor countries’ own national budgets too. In fact, this is right at the core of our strategies.

The joy of tax is that it’s a positive sum game: good policies can ensure better outcomes for everyone, in countries at all income levels. Shifting narratives about what constitutes effective aid can help us deliver tax justice.

The Tax Justice Network fights for fairer tax systems, and fights against tax havens and the abuses they facilitate. We depend on support from people who share our belief in doing the right thing for a fairer world. If you’d like to support us to carry on our vital work, please click here to make a donation.

Related articles

Admin Data for Tax Justice: A New Global Initiative Advancing the Use of Administrative Data for Tax Research

New Tax Justice Network podcast website launched!

People power: the Tax Justice Network January 2024 podcast, the Taxcast

ESCOLA DE HERÓIS TRIBUTÁRIOS #56: the Tax Justice Network Portuguese podcast

The People vs Microsoft: the Tax Justice Network podcast, the Taxcast

New Tax Justice Network Data Portal gives unparalleled access to wealth of data on tax havens

5 ways Big Tobacco is making you pay more tax

Often overlooked, transparency at the tax administration level is key to holding governments accountable

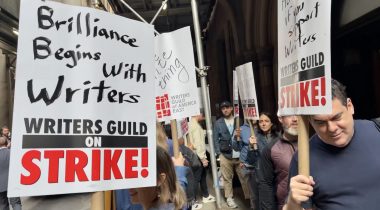

How Hollywood gaslights WGA strikers, Uncle Sam and Darth Vader about its profits