Andres Knobel ■ It’s time for countries to start publishing the data they’re collecting under OECD’s Common Reporting Standard

Some financial centres already publish detailed data on cross-border bank account holdings. The OECD’s Common Reporting Standard is now underway, generating lots of this data: it’s time to publish it all. This would cost nothing, breach no confidentiality, and deliver large benefits.

Another 50 countries this year are set to exchange information automatically about cross-border bank account holdings, adding to the 50 or so that are already doing so under the OECD’s Common Reporting Standard (CRS). This transparency scheme will enable more governments to see bank account details for their own taxpayers who have parked wealth in other countries, so they can tax them appropriately.

As we have pointed out on several occasions, the CRS has many weaknesses. One big hole is the United States: it is very happy to receive such information from other countries under its (technically similar) FATCA scheme, but it is unwilling to share much information in the other direction (about the bank accounts of other countries’ citizens held in the US.) Switzerland, for its part, is participating but has resolved to victimise developing countries by throwing up hurdles for them, and postponing exchanges with them until at least 2019.

There are also big, general loopholes in the CRS which we have been warning about since 2014. One of the biggest is golden visas and fake residency schemes. With this loophole, the banks do collect the information on taxpayers according to normal CRS rules — then they simply direct that information towards the fake residency jurisdiction, rather than the taxpayer’s real place where they are required to pay tax. The fake jurisdiction receives the information, laughs, and and does nothing with it. We supported the OECD’s model “Mandatory Disclosure Rules” for schemes that are designed to circumvent the CRS (which, despite the name, are not mandatory.) We proposed improvements, and, crucially, the publication of data. Yet nothing has been done yet.

All this raises big questions. Should we trust a system with loopholes? More profoundly, should we trust the same authorities that have failed repeatedly to prosecute wealthy people caught red-handed in Swiss Leaks and other investigations? Should we trust Panama, now that the Panama Papers scandal has exposed the nature of what has been going on in that tax haven? Should we trust Luxembourg, after Luxleaks? Just because governments have signed an international agreement, doesn’t mean they will abide by it.

We can’t. But there is something else we can do: get the data on non-resident bank accounts, broken down by country, so that citizens can find out where their wealthiest citizens’ wealth is being stashed. That is a real starting point for action. TJN has already produced a template for CRS statistics, explaining what it should include and how useful it will be. No account holders would be identified so it breaches no confidentiality, and it has no extra cost: banks have already collected all the relevant data and reported it to the relevant authorities. But as far as we are aware, only Australia has approved a law to publish (a partial version of) the proposed CRS statistics.

But why are other countries so quiet?

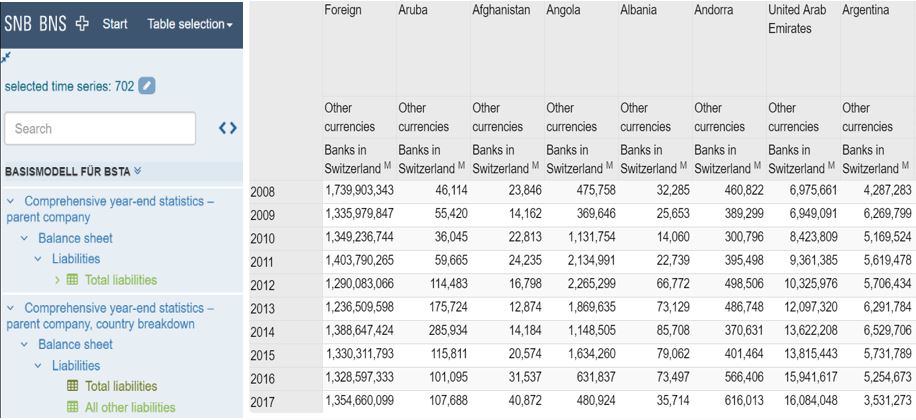

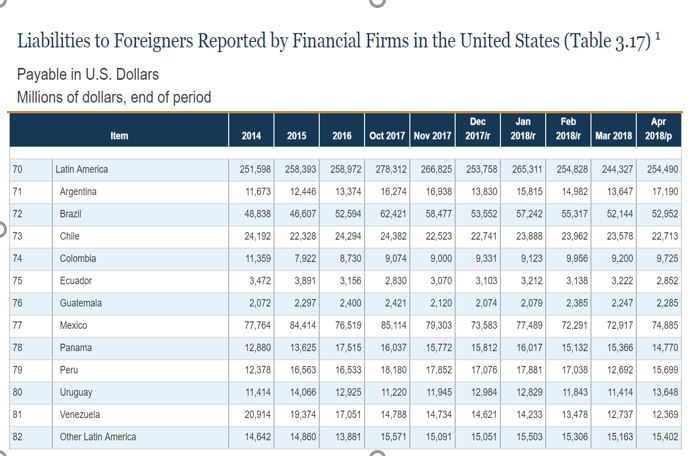

Oddly enough Switzerland and the United States, two of the worst tax havens – first and second in the financial secrecy index ranking –already publish relevant information, showing that these banking statistics, classified by country, can be published, breaching no confidentiality:

Unfortunately, neither the US nor the Swiss data is very clear. It includes “total liabilities”, not just “deposits”, and it’s not entirely evident whether it only includes funds in both countries, or also money in branches outside both countries. [CRS statistics, we’ve proposed, would be much more clear cut: they would refer directly to data on accounts belonging to non-residents, specifying whether it’s a deposit account, a custodial one, etc.] What is more, this is only information about accounts where the legal owner is registered to a particular country: many accounts are held by other structures such as shell companies, where the beneficial owner is hidden. So a lot of wealth, probably most of it, is hidden or misreported in this data.

Yet for all these shortcomings this data is still useful, and we can use it to illustrate how useful CRS data could be (The US data isn’t like-for-like comparable with the Swiss data, but let’s pretend for the sake of illustration that it is.)

For example, Argentine media outlets reported that Argentina, an early adopter of the CRS, in 2017 received information about 35,000 foreign accounts, mainly in Belgium, Bermuda, Cayman, France, Isle of Man, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Spain, and the UK.

Interestingly, the US and Switzerland aren’t mentioned – because Argentina has no agreement to automatically exchange banking information with the US, and exchanges with Switzerland will only start in 2019.

But because of the data those two countries publish, Argentine authorities still have cards to play.

On the one hand, they can check if the total amount of money Argentines declared in US banks matches what the US Treasury reports as belonging to Argentines (see the picture above). If Argentines declared less, then authorities can start investigating who has failed to declare their holdings, or make specific requests for information. The same goes for Switzerland.

Another option is to look at what happened with deposits in the US and Switzerland since the CRS rules became known (considering that Argentina will eventually receive information from Switzerland but not from the US). Interestingly, assuming that we are comparing apples to apples (which we cannot certify yet using this data), Argentine deposits in Switzerland fell, while they increased in the US.

From this, it seems likely that much, if not most, of the USD 3 billion belonging to Argentines that left Switzerland ended up in the US.

Knowing this kind of information would prove enormously useful to tell the public where Argentines are holding their money abroad, and also to detect possible avoidance schemes (if Argentines are actually taking their money away from Switzerland and putting it in the US).

If all or most countries (or at least all major financial centres) published these details, a world of new patterns and knowledge would emerge, upon which citizens and responsible governments could act.

Now imagine if all CRS adopting countries published this data not just at the legal owner level – as the US and Switzerland currently do (still allowing individuals to hide behind e.g. a company that is holding the bank account), but if countries also published this data at the beneficial owner level (identifying also the individuals who may be hiding behind a shell company that holds the bank account). The CRS framework already requires beneficial ownership information to be collected and exchanged, so countries are already in a position to publish this aggregated banking data (both at the legal and beneficial ownership level) at no extra cost. A lot more data would emerge, no confidentiality would be breached, and a host of benefits could flow.

What are we waiting for?

Related articles

Malta: the EU’s secret tax sieve

The tax justice stories that defined 2025

2025: The year tax justice became part of the world’s problem-solving infrastructure

‘Illicit financial flows as a definition is the elephant in the room’ — India at the UN tax negotiations

Tackling Profit Shifting in the Oil and Gas Sector for a Just Transition

Follow the money: Rethinking geographical risk assessment in money laundering

Democracy, Natural Resources, and the use of Tax Havens by Firms in Emerging Markets

One-page policy briefs: ABC policy reforms and human rights in the UN tax convention

The Financial Secrecy Index, a cherished tool for policy research across the globe