Alex Cobham ■ Beginning of the end for the arm’s length principle?

The European Commission has released a statement which could well signal the beginning of the end for the OECD’s international tax rules, and the arm’s length principle on which they are based.

The current rules, which date to decisions taken at the League of Nations in the inter-war years, are based on the assumption that the ‘right’ price for a trade between different companies within the same multinational group is the price which would apply for the same transaction between unrelated parties. This “arm’s length” price is therefore taken as the basis to evaluate all such intra-group trade (transfer pricing). But of course this flies in the face of the economic rationale for the existence of multinationals, which is precisely that they can be more profitable as a group than if the individual entities operated separately – so it’s impossible that arm’s length prices could be the ‘right’ ones to determine where taxable profit should arise.

Bear in mind that the EU was one of the major actors in the OECD Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) process, which ran from 2013-2015 and was the biggest effort to patch up the arm’s length principle and transfer pricing for decades. But before the ink is dry on the legislative measures that have followed, the Commission is making the sort of statements that you’ve heard for years – but only from us at the Tax Justice Network. In particular, this (emphasis in original):

“The current tax framework does not fit with modern realities… The first focus should be on pushing for a fundamental reform of international tax rules, which would ensure a better link between how value is created and where it is taxed.”

The Commission is not calling for a ‘BEPS II’, with some further patches to the system. The “fundamental reform” in question can only be the replacement of the arm’s length principle with a unitary approach that recognises multinationals’ profit occurs at the group level, not in individual subsidiaries – and needs to be taxed on the same basis.

This could be the crucial tipping point that signals the end for the OECD’s international tax rules. The US already takes a unitary approach to taxing companies inside its border, and earlier this year seriously considered a destination-based cashflow tax for multinationals that would do the same. The G77 group of around 140 lower-income countries has repeatedly expressed their dissatisfaction with the BEPS outcomes. And now the EU has called for “fundamental reform”.

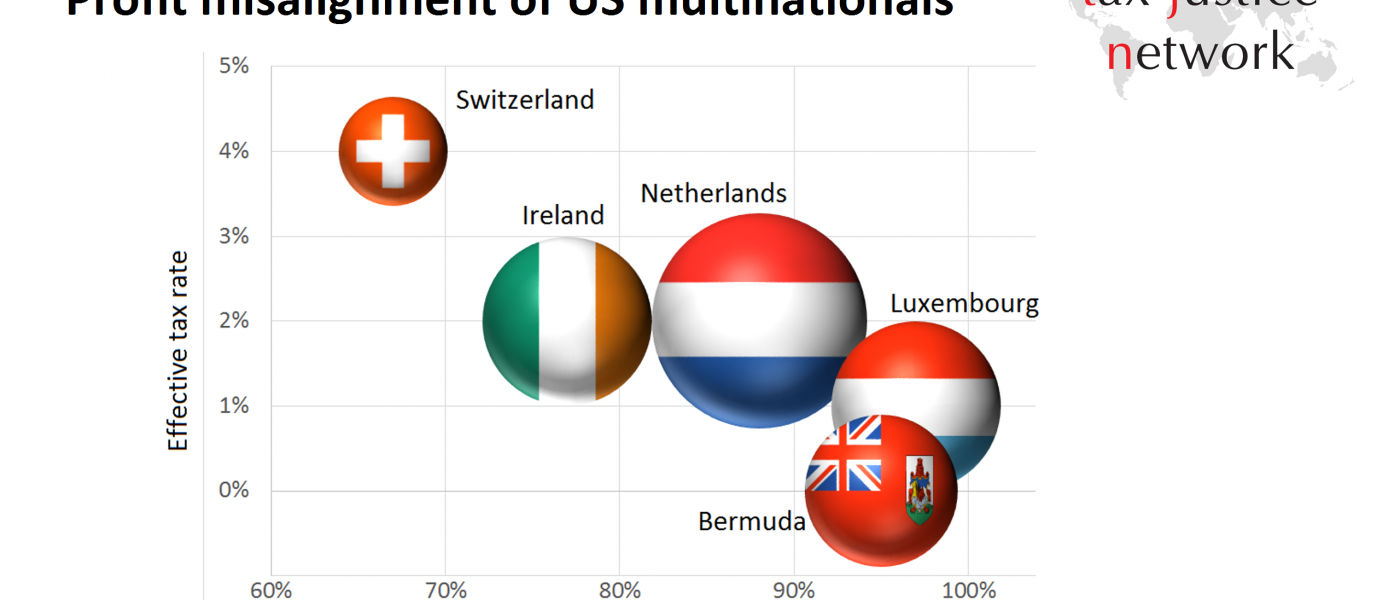

So there may no longer be a major economic actor left to champion the arm’s length principle. And that, finally, would allow consideration of unitary approaches, including formulary apportionment, which would actually deliver what everyone* wants: greater alignment between profits and the location of real economic activity.

*Well – everyone except perhaps those who make their money from misalignment (e.g. see figure above, from our study of US multinationals forthcoming in Development Policy Review); or those who make their money from advising on how to create misalignment…

PS. The Commission position, incidentally, is framed around digital economy taxation, and also raises the possibility of some shorter-term changes that could raise serious issues themselves.

PPS. The OECD, which until recently had said that further work on the digital economy was some way off, has clearly seen the wider threat – announcing today a rushed public consultation. (h/t @SoongJohnston)

Related articles

Indicator deep dive: ‘Royalties’ and ‘Services’

Proposal for ‘Business in Europe: Framework for Income Taxation’ (BEFIT): A wrong turn in the right direction

2 February 2024

Formulary apportionment in BEFIT: A path to fair corporate taxation

31 January 2024

New Tax Justice Network podcast website launched!

Monopolies and market power: the Tax Justice Network podcast, the Taxcast

A year the tide turned in the fight for tax justice

Taxing Wall Street: the Tax Justice Network December 2020 podcast

$427bn lost to tax havens every year: landmark study reveals countries’ losses and worst offenders

The State of Tax Justice 2020

20 November 2020

Interesting discussion. As an economist I might put this differently. Yes multinationals abuse what they call the arm’s length principle but in my view this is because accounting firms and law firms exploit poorly written regulations to their advantage. This abuse of the arm’s length standard could be countered if we drop the regulations and ask sensible economic questions. BEPS Action 8 went part of the way in some of its wisdom that many of the representatives of multinationals are just ignoring. BEPS Action 9 had one brilliant paragraph (#63) but this wisdom is simply getting buried. Now you might ask what about the economists at the law firms and accounting firms. I hate to say this but they have become advocates and not economists. Now if we had stronger economists working for the tax authorities – things might be different.