Nick Shaxson ■ Risk mining: what tax avoidance is, and exactly why it’s anti-social

Recently we wrote about a remarkable blog by Jolyon Maugham, a tax barrister, a view from the front lines, which we’ll repeat again today, because it’s so startling:

“I have on my desk an Opinion – a piece of formal tax advice – from a prominent QC at the Tax Bar. In it, he expresses a view on the law that is so far removed from legal reality that I do not believe he can genuinely hold the view he says he has. At best he is incompetent. But at worst, he is criminally fraudulent: he is obtaining his fee by deception. And this is not the first such Opinion I have seen. Such pass my desk All The Time.

The “he” in question, I shall not name. But the brief description in the above paragraph will be sufficient to enable that part of the tax profession that regularly uses tax Counsel to narrow the possibilities down to slightly under half a dozen names. These are the Boys Who Won’t Say No – the “Boys” for short – and we all know who they are.”

There are surely similar groups in many countries. A second eye-opener was this:

“The fees that can be generated from bringing a planning idea to market are substantial: I am aware of instances where a single planning idea has generated fees of about £100 million pounds for the House.”

And the blog itself is makes useful reading for those interested in the nuts and bolts of how this activity actually happens, at the coal face – and it has caused quite a stir, too.

This brings us to the main topic of our blog: a new paper by UK barrister (and TJN Senior Adviser) David Quentin, entitled Risk-Mining the Public Exchequer.

Though less immediately startling than the above blog, it has profound implications for the tax avoidance debates, and we think will be talked about for years.

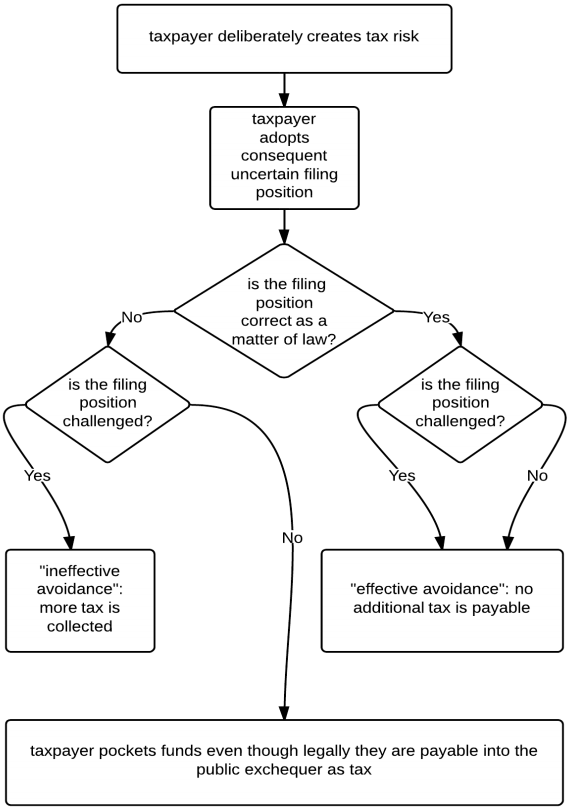

In a nutshell, it looks at the point when legitimate tax planning becomes tax abuse, and notes that from that point onwards – when tax advice deliberately creates ‘tax risk’ for the public authorities (i.e. the risk that, if challenged, the tax filing position would fail,) anti-social tax avoidance begins. This, he notes,

“extracts value from the public exchequer by seeking to withhold money, some of which should as a matter of law be paid into it.”

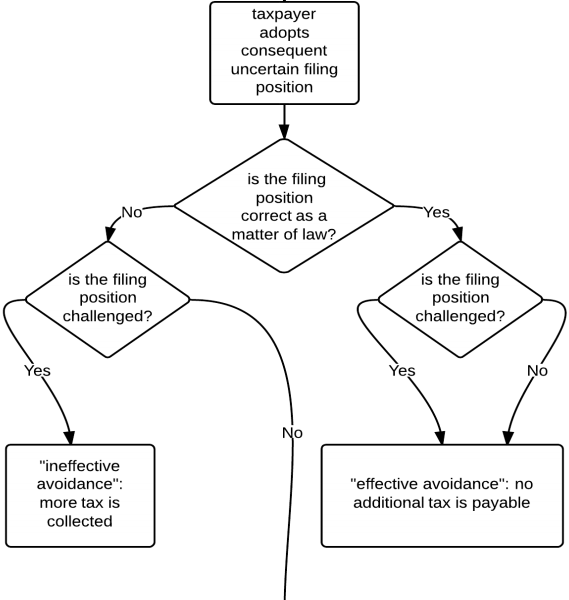

This is what he calls risk mining. Take a look at the diagram, which is pretty clear.

It is that bottom box where the anti-social behaviour is clearest, but note that the anti-social part of it begins at the top of the graph where the uncertainty is introduced. The order of this flow is important here.

As an aside, we should remark that one thing that does annoys us on a regular basis is a tendency for journalists to write about a particular tax structure that a company or individual has employed, and then go on to say that ‘this is perfectly legal’ (or, worse still, ‘this is perfectly legitimate.’) They often do this for fear of attracting libel suits, which is understandable, but the problem with it is that factually, they are wrong to write this.

They are wrong because they usually cannot know if the tax structure is ‘legal’. If the structure is newsworthy enough for them to be writing about it, then it is likely to be an ‘aggressive’ tax structuring arrangement, which the courts have not explicitly approved. It is just sitting there, perhaps with the taxpayer and their advisers simply trying their luck with something pretty egregious and hoping they will get away with it. Even if it is not particularly egregious, if there’s uncertainty then there’s ‘risk mining’ going on, as explained a little later.

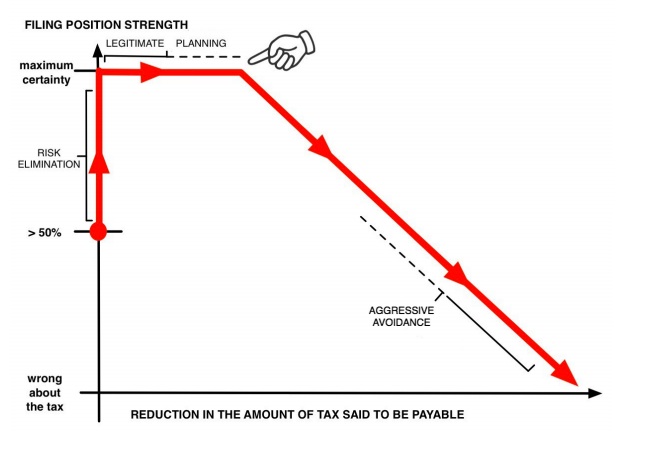

This brings us to the age-old question of where you draw the line between legitimate tax planning and tax avoidance. Quentin’s new paper cuts through the reams and reams of woolly thinking out there and makes more clear points, notably this:

“Contrary to popular and even expert belief, there is in fact a clear dividing line between “legitimate tax planning” and “avoidance”. It is here. [where the finger points to in the picture below]”

One might characterise the flat part of the line as the part where the taxpayer avoids tax cock-ups, and it then it moves into the territory where uncertainty begins as to whether or not the tax filing position is right.

The sloping part of the curve is, he says, where avoidance begins. Conventional definitions of avoidance are unhelpful, he says:

“Avoidance is usually defined as reducing tax payable by legal means, but in fact the opportunity that is increased as you head down the avoidance section of the tax advice risk curve is the opportunity to not pay tax which is legally payable.

. . .

That opportunity is created at the expense of taxpayers generally, and is therefore anti-social conduct deserving of the opprobrium attaching to the phrase “tax avoidance”.”

Our emphasis added. In other words, that first part is saying that those journalists writing about certain tax shenanigans being ‘perfectly legal’ have got it wrong, and that second part is saying that TJN and our allies are quite right to be concerned about tax avoidance.

Another important point is that this is not seeking to identify a dividing line between tax avoidance and tax evasion – both avoidance and evasion can fit into this framework above.

This all clearly requires quite some thought, and there is plenty more in the paper that needs considering. Read the paper – it’s not that long – to get the full sense of it: it is clearly a very important contribution to the debate.

There’s also another summary of the paper here, which goes further than our blog and is well worth reading if you’re interested.

Further updates from Quentin on this and other matters, here.

A “core and penumbra” update, saying much the same thing, here.

Oh, and who exactly are The Boys Who Won’t Say No? We don’t know for sure, but Maugham has offered a vague pointer.

Related articles

Malta: the EU’s secret tax sieve

The bitter taste of tax dodging: Starbucks’ ‘Swiss swindle’

The tax justice stories that defined 2025

Admin Data for Tax Justice: A New Global Initiative Advancing the Use of Administrative Data for Tax Research

2025: The year tax justice became part of the world’s problem-solving infrastructure

‘Illicit financial flows as a definition is the elephant in the room’ — India at the UN tax negotiations

Tackling Profit Shifting in the Oil and Gas Sector for a Just Transition

The State of Tax Justice 2025

Follow the money: Rethinking geographical risk assessment in money laundering

My inquiry is ex-wife dodged paying her taxes for eight years, by claiming all three of my minor children as dependents when our court decree granted them to myself. I was always required to forward a yearly copy of decree along with my filing taxes. She took advantage by way of early filing using them as dependents and was able to avoid paying her taxes properly for all those years until I was able to be represented by a tax advocate to which won my original IRS argument proving my entitlement for the deduction of the minor children. But since it took over ten years for the IRS to properly accept this outcome, she was able to avoid any tax adjustments being placed upon her previously filed tax accounts. I spent many hours trying to force the IRS to penalize or reveal this type of account files but still made no headway. My only given outcome here is that the IRS stated it would not reveal any account info or filing amendments being placed upon her previously filed tax years, but this cost me well over fifteen thousand dollars plus interest for not being able to claim them for all those years. My overall problem is that most attorney’s that I’ve attempted to retain to take her back to family court and attempt to recover my loss, I’m told by them that the original attorney would be the only legal representative to present this type of action! Problem is my original attorney died three years after the divorce was granted and I can’t find another willing to take it all on.

Just the feeling of being stuck between a hard place and a rock on this one! Any thoughts?

Thanks for checking out my story here.

Mark from Mount Olive, Illinois