Nick Shaxson ■ IMF: tax havens cause poverty, particularly in developing countries

The IMF has a major new Policy Paper out entitled Spillovers in International Taxation, looking at the effects that one country’s tax rules and practices can have on others.

The IMF has a major new Policy Paper out entitled Spillovers in International Taxation, looking at the effects that one country’s tax rules and practices can have on others.

Of course this is a Staff Report and the IMF would never be so rude to some of its most powerful member states as to explicitly say what is in our headline – but that’s what we read between the lines. “Spillovers” in international tax are all about tax haven activity, particularly when those spillovers are deliberately crafted.

Now that we’ve read it, we conclude that this is a really important document. It tears apart much of the prevailing OECD tax consensus that has dominated international tax for the last century.

We are delighted to see that it convincingly takes the side of developing countries: not only taking sides in big current political fights (such as India vs. Vodafone) but peppering the report with suggestions how developing countries can fight against all the erosion.

This makes a really refreshing change from the standard (often well-justified) stories about IMF programmes laying waste to developing countries.

The IMF says the aim of this exercise – which, by the way, is clearly written and should be palatable to interested non-experts – is to complement the OECD’s BEPS (Base Erosion and Profit Shifting) project to help countries protect themselves from tax abuses, by looking at the spillovers. However, buried deep in the text are some devastating criticisms of BEPS too – notably that it doesn’t properly address crucial issues of unfairness towards developing countries. The report notes:

“New results reported here confirm that spillover effects on corporate tax bases and rates are significant and sizable. . . . Spillovers are especially marked and important for developing countries. . . . The amounts at stake in a single tax planning case now quite routinely run into tens or hundreds of millions of dollars.”

And, in terms of the tax base (that is, which part of cross-border income that developing countries get to tax), there’s some startling quantification:

“The spillover base effect is largest for developing countries. Compared to OECD countries, the base spillovers from others’ tax rates are two to three times larger, and statistically more significant. . . . The apparent revenue loss from spillovers. . . is also largest for developing countries.”

Our emphasis added. Wow. And we’d agree with the next bit, of course:

“The institutional framework for addressing international tax spillovers is weak. As the strength and pervasiveness of tax spillovers become increasingly apparent, the case for an inclusive and less piecemeal approach to international tax cooperation grows.”

That may be a gentle dig at the OECD, for not being ambitious enough. And there’s plenty more: the IMF notes.

“[a] concern sometimes expressed that the system allocates too little tax base to developing countries”

In other words, considering all the different bits and pieces of income that flow from a cross-border investment from a rich country to a poor one, most of them get taxed by the rich country, leaving relatively little on the table for the poor country. What a surprise. And it notes the harmful effects of tax ‘competition’:

“The pervasiveness of the tax incentives that the IMF and others have long stressed as significantly undermining revenue in developing countries may to a large extent be a spillover reaction to policies pursued in other countries: a clear instance of tax competition.”

Tax competition is the widely used term; but Tax Wars is the less economically illiterate term. The IMF also notes that – unlike the global trade system – the tax system is an uncoordinated and pretty disastrous hodge-podge. It contains an interesting statistical nugget: “the increased importance of intra-firm transactions (about 42 percent of the value of U.S. goods trade in 2012” (consistent with the idea that about half of world trade happens inside multinational corporations)

The IMF report takes a swing or two at the OECD’s BEPS process. For instance, in a section on tax treaties which allocate taxing rights among countries, the IMF notes that not only are the OECD models (that are generally the basis for these treaties) skewed in favour of richer countries, as we and other have often remarked, but it also adds:

“At issue here are deeper notions as to the ‘fair’ international allocation of tax revenue and powers across countries (which current initiatives do not address).”

That is a small sentence buried in the text, but it’s devastating. And the IMF notes that defending the OECD consensus may even end up not serving the self-interest of OECD countries:

“Arrangements that seem to contradict broad perceptions of fairness, even if those are imperfectly articulated, may increasingly give rise to unilateral domestic measures to change them—with a consequent risk of uncoordinated defensive measures even further undermining the coherence of the international tax system.”

Treaty reform, it seems is essential, as it notes in its key messages for developing countries:

The “sign treaties only with considerable caution” reminds us of a recent fiery intervention by Lee Sheppard, in which she urges developing counties not to sign these kinds of tax treaties.

Now here’s something else that’s fascinating. The IMF appears to be taking India’s side in its recent tax tussle with Vodafone. Get a load of this:

“The tax treatment of gains on indirect transfers of interests in assets is a controversial issue—and one of particular importance to many developing countries.”

This is where a multinational has an asset in a developing country, and that asset rises in value. It wants to sell the asset – but if it just sells it straight, it may have to pay capital gains tax on those gains. So instead the multinational sets up a shell company in a tax haven, to own the asset. This time it merely sells the shell company (which owns the asset). The sale is recorded in the tax haven, which doesn’t tax capital gains. Bingo! Wealth is transferred from a poor country to wealthy shareholders of the multinational.

This is exactly the issue in the India-Vodafone fight – which the IMF explicitly mentions, along with billion-dollar cases in Mauritania and Mozambique (p70). And the IMF’s conclusion on this?

“The laws of many developing countries need strengthening if they are to tax gains on such indirect transfers.”

Go get ’em!

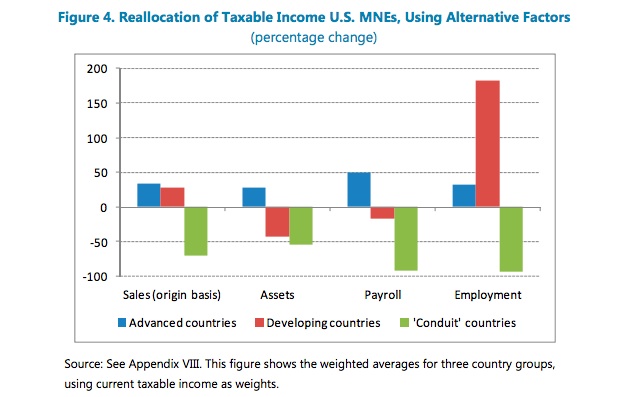

On the crucial issue of the OECD’s Arm’s Length Method (otherwise known as the Arm’s Length Principle, or ALP), which we and many others have criticised extensively, the IMF recognises that it is badly broken though it does not fully endorse a move towards the main alternative, unitary taxation with formula apportionment (FA). Such an approach would tackle many of the existing problems, it argues, but would introduce new difficulties – and would not necessarily shift tax bases towards developing countries. Yet it adds:

“this approach, rather than one based on ALP, is so common at subnational level—indeed there seems to be no subnational CIT that does not use some form of FA—suggests that it has at least some merit in taxing firms operating across highly integrated economies.”

(That bit in bold is our emphasis, because we (or at least today’s TJN blogger) didn’t know that.)

Whether or not developing countries would benefit from application of formula approaches internationally, the IMF notes that it depends on which kind of formula were applied:

The IMF urges ‘closer study’ of partial approaches based on formula apportionment, however, including hybrid approaches and ‘profit split’ methods which involve allocating taxable income between countries on a formula basis, but at a transaction level rather than at the level of the multinational group.

To finish, here’s another little bomblet:

“[it has been argued that] low tax and conduit countries can improve the efficiency with which capital is allocated. These considerations generate heated dispute, but remain essentially uninformed by empirical knowledge.”

It is almost funny how the IMF savages some of the tax havens’ central arguments in their self-defence (see more here). The 2006 paper they cite in this respect (Desai, Foley and Hines) and earlier iteration by Hines in particular have become totemic for tax havens in their defence. “Uninformed by empirical knowledge” is perhaps as damning a statement as you will get from the scrupulously polite IMF.

There is plenty more in this report, but these are probably the main points, tax justice-wise.

To summarise: the IMF seems to be carving out new space in this arena with more time for the interests of developing countries, in some contrast to the OECD – which is, after all, a club of rich countries, and experience shows tends ultimately to bat for the interests of its member states.

A welcome addition to the literature.

Related articles

The tax justice stories that defined 2025

Let’s make Elon Musk the world’s richest man this Christmas!

2025: The year tax justice became part of the world’s problem-solving infrastructure

Bled dry: The gendered impact of tax abuse, illicit financial flows and debt in Africa

Bled Dry: How tax abuse, illicit financial flows and debt affect women and girls in Africa

9 December 2025

The myth-buster’s guide to the “millionaire exodus” scare story

Money can’t buy health, but taxes can improve healthcare

The elephant in the room of business & human rights

UN submission: Tax justice and the financing of children’s right to education

14 July 2025