Franziska Mager, Bob Michel ■ Breaking the silos of tax and climate: climate tax policy under the UN Framework Convention on International Tax Cooperation.

Reforming the international tax system is our only shot to find the means to mobilise missing climate finance in the necessary order of magnitude. The current international tax regime leaves trillions of dollars of tax revenue on the table because of its inability to eradicate tax abuse and its under-taxation of wealth. The current regime also fails to help Global South countries maximize their potential for domestic resource mobilisation, which is much needed to finance their fight against climate crisis. The persistent problem of financial secrecy further worsens the climate crisis problem, and thereby increases the climate finance bill.

In this blog, we’ll show that the future of inclusive tax cooperation on the interface of tax and climate lays with the United Nations Framework Convention for International Tax Cooperation, negotiations on which will start in 2025.

Along with this blog, we’re publishing today a new briefing on seven principles of good taxation for climate finance.

The climate crisis is a story of inequality that comes with a daunting price tag

The climate crisis is a story of multiple inequalities coming to a head.

There is inequality of responsibility for the climate crisis: to this date, the Global North is estimated to have contributed 92% of cumulative greenhouse gas emissions. Yet the Global South faces the brunt of the consequences, while having contributed the least to the problem.

On top of that, the means to finance a way out of the crisis are deeply unfairly distributed: the Global South, having the least blame and most burden to bear, has dramatically far less financial means than the Global North to put towards mitigating the climate crisis.

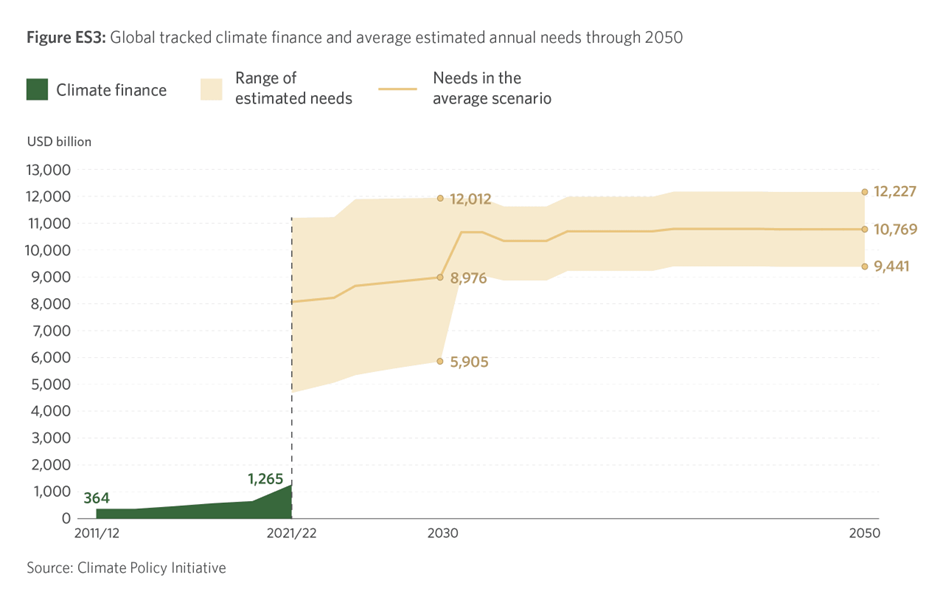

Let there be no mistake: a lot of money is required to deal with the climate crisis. Estimates by the Climate Policy Initiative show that the combined annual cost to deal with the climate crisis in all countries around the globe will reach $9 trillion by 2030. Every moment of in-action increases this bill further. Currently, the annual amount dedicated to climate finance hovers below US$1.5 trillion – negligible compared to what the world really needs.

Climate finance: money for what and how much?

What exactly are these mindboggling sums needed for? Climate finance essentially serves three purposes:

- Climate mitigation, or measures to reduce the sources of greenhouse gas emissions or increase storage of emitted gases (eg the establishing of a cleaner transportation system or the increasing of forest sizes);

- Climate adaptation, or measures to adjust society to the current and future effects of climate crisis (eg the building of flooding walls);

- Loss and damages, or funding to deal with the negative economic consequences of climate crisis that go beyond what people can adapt to (eg the cost to repair damages resulting from extreme weather events)

It is clear that the richer countries of the Global North need to pick up a large chunk of the South’s climate finance bill. This is needed not just to aid these countries’ mitigation efforts, but also to assist in climate-proofing societies and paying for climate damages suffered by those that bear little responsibility.

But how much external financing from Global North to Global South is enough to give developing countries a chance to adapt, mitigate and pay for ongoing loss and damage? These dimensions of a new collective quantified goal (NCQG) for climate finance were the topic of negotiations in Baku during the latest Conference of the Parties to the Paris Agreement (COP29).

Prior to the COP, UN Trade and Development (UNCTAD) released new estimates which reveal that developing countries would need about $1.1 trillion in annual climate finance from 2025 and some $1.8 trillion by 2030. Developed countries would need to fund at least three quarters of the funds required by their developing counterparts. Alarmingly, only one-fifth of developing countries’ financing needs is expected to come from domestic resource mobilisation (DRM), leaving around up to $1.3 trillion a year to be derived from developed countries.

Importantly, the climate finance should also meet certain qualitative standards. Currently, over 3.3 billion people live in Global South countries that spend more on interest than on education or health. Climate finance to Global South countries only makes sense if it expands the fiscal space of those countries rather than stifling development any further be increasing countries’ level of indebtedness. As such, the goal of climate finance should be rights and needs-based, and allocated primarily in the form of grants rather than loans. There must also be no double-counting: the funding should be additional to the existing official development assistance (ODA).

That time of the year: post-COP disappointment

At COP29, not much came to fruition of the ask for a strong commitment from the Global North to fair climate finance of an amount upwards of $1.3 trillion a year by 2035. In Baku, developed countries agreed to channel ‘at least’ $300bn a year into developing countries by 2035 to support their efforts to deal with climate crisis, a fraction of the expected real needs. The underwhelming, new climate finance goal has left developing countries bitterly disappointed. As Panama’s climate envoy put it: “this very low level of finance … means death and misery for our countries.”

There is, of course, another way.

Instead of rich countries essentially claiming they cannot afford to deal with the climate crisis they created because public finances are tight, public finances themselves need to be reformed. That means looking at the elephant in the room of climate finance diplomacy: the international tax system.

What’s tax got to do with it? Everything.

Tax is our social superpower. Not only does tax generate the revenues needed to fund public goods, it also provides a tool to correct societal wrongs and correct inequality in society. And it provides the main way to redistribute means among citizens.

This is not different in the case of climate finance.

Whether funds are raised through domestic resource mobilisation in the Global South or via public financing in the North, nearly all of it originates as tax revenue. Given the magnitude of the climate finance gap, our tax systems need to perform to serve climate mitigation and adaptation efforts.

Because of climate crisis, we cannot afford to play fast and loose with tax and financial transparency.

Currently, we play loose.

In our recent State of Tax Justice 2024 report, we show that countries lose US$492 billion of tax revenue a year o multinational corporations and wealthy individuals using tax havens to underpay tax.

US$492 billion from corporate and private cross-border tax abuse is of course a far cry from the US$9 trillion needed for global climate finance. However, if these losses were to be eliminated, revenue gains would be much higher because if the loopholes through which taxable profits leak to tax havens are closed, countries will no longer feel pressured to keep tax rates low.

This pressure and the knock-on effects of corporate tax abuse in particular additionally cost countries what gets called the “indirect costs” of cross-border corporate tax abuse. The IMF estimates that these “indirect costs” are three to six times greater than the “direct costs” of corporate tax abuse. Of the US$492 billion countries lose a year, two-thirds (US$348 billion) is due to corporate tax abuse – this is the “direct costs”.

Eliminating global tax abuse would mean both direct and indirect costs, so tax revenues from multinational corporations wouldn’t rise by hundreds of billions a year but potentially by trillions. A global increase of the average effective tax rate on corporate profits by the biggest multinational enterprises by few percentage points would likely result in additional revenue gains in the hundreds of billions. Such a ‘climate finance corporate surcharge’ should be earmarked to serve countries’ climate finance obligations.

If, in addition to closing the loopholes for offshore income tax abuse, countries would introduce a progressive net wealth tax on the richest taxpayers, trillions of additional revenue can be gained. As pointed out by Oxfam, the richest 1% emit as much planet-heating pollution as two-thirds of humanity.

According to our recent calculations, a net wealth tax, based on the one implemented in Spain, of roughly 2% to 3% on the richest 0.5% would yield an annual revenue of US$2.1 trillion a year. Not only would a climate finance solidarity surcharge address this rampant inequality, it would also be the ultimate implementation of the polluter pays principle.

Tax havens not only help drain critical public resources from countries, they also conceal fossil fuel financing and enable environmental crimes. Unless we address ‘greenlaundering’ and the financial secrecy which hampers mitigation efforts through fossil fuel divestment, much of climate action is nothing more than rearranging the deckchairs on the Titanic. To put things in perspective, last years’ numbers show that tax havens cost governments as much tax revenue as the yearly global cost of climate losses and damages.

The mutual finger pointing of tax v. climate

The price tag of the climate crisis makes it so that we have little choice than to make fundamental changes to the current architecture of international tax and architecture. We simply cannot afford the massive corporate tax abuse, the undertaxed private wealth and the financial secrecy that hinders the green transition. But to make change happen, we should be able to rely on global tax governance structures that are inclusive and effective, and accept the premise that tax policy and climate action are two sides of the same coin.

At the moment, such structures do not exist. The OECD and G20 – limited membership organisations that have monopolised global tax governance – are shockingly masterful in entrenching the separate silos of tax and climate. The OECD’s global minimum tax regime under Pillar Two is a case in point.

This byzantine tangle of rules implements the fundamentally good idea that corporate profits should be taxed at a minimum level. The new rules include a provision which essentially allows certain profits to be taxed below the minimum level if they reflect economic substance in the form of real assets and employees. A laudable idea, but in light of the climate crisis, can the world afford this type of neutrality? Implementing a global system which incentivises oil business to grow their business because bigger and more oil rigs means a larger allowance for undertaxed profits seems absurd.

The cross-border effects of the minimum tax rules have triggered a never-before-seen global review of corporate tax incentives. The fact that the climate crisis is completely ignored as a parameter for these reviews is a huge, missed opportunity to unleash the power of corporate taxation for the sake if climate action.

Unsurprisingly, the recent Rio G20 Declaration of November 2024 is similarly disappointing on the links between tax and climate. For example, the G20 ‘reiterates its commitment’ to the Two-Pillar Solution, including the (climate crisis ignoring) minimum tax regime. As for climate action itself, the G20 leaders do not raise the tax topic and simply ‘encourage each other to bring forward net zero greenhouse gas emissions and climate neutrality commitments’.

This lack of ambition by the self-proclaimed leaders of the world is unacceptable, especially to those (unrepresented) countries most affected by climate crisis. It is to this backdrop that a number of small developing island states are currently requesting the International Court of Justice to formally condemn the lack of climate action as a violation of international law.

Unfortunately, the Paris Agreement is also not very helpful to further the ‘tax meets climate’ agenda. The Paris Agreement is obviously a landmark in the multilateral fight against climate crisis as it sets all-important carbon emission-reduction goals. But these so-called nationally determined contributions (NDCs) are non-binding pledges and do not come with concrete agreements on coordinated action to meet these national targets.

The Paris Agreement also doesn’t sufficiently address the issue of unequal burdens faced by the Global South and historical responsibility. In recent negotiations by the conference of parties, additional goals like the loss and damages fund (COP28 in 2023) and the new collective quantified goal (NCQG) for climate finance were partically agreed. But the outcomes are too little, too late and too unambitious.

To make things worse, tax is not mentioned once in the text of the Paris Agreement, nor has it ever been the dedicated focus of any COP, nor will it likely be in the future. Just like the G20 points to the Paris Agreement to deal with climate, the Paris Agreement essentially points to elsewhere when it comes to tax in relation to climate. That’s a shocking reality, given tax’ crucial role in climate action and climate justice, whether through domestic resource mobilisation in the Global South, efficient and equitable revenue raising for climate finance in the North or effective climate mitigation and adaptation efforts in all countries south, north or in between.

It’s clear that at the intersection of tax and climate, the world is currently missing an important piece of the global governance puzzle. But change may be within reach.

A new dawn: the UN Framework Convention on International Tax Cooperation

On 27 November 2024, the world may have given itself a lifeline when it comes to solving the tax and climate governance issue. On that day, a landslide majority of countries voted in favour of the adoption of a UN General Assembly Resolution which formally kicks off, as of 2025, the negotiations for a United Nations Framework Convention on International Tax Cooperation (UNFCITC).

The Resolution also adopted the draft Terms of Reference (ToR) that were developed by an Ad Hoc Committee over the course of 2024 and which will guide the upcoming negotiations. The terms provides that ‘a holistic, sustainable development perspective that covers in a balanced and integrated manner economic, social and environmental policy aspects’ is one of the principles and commitments that should be included in the Convention. The terms lists ‘tax cooperation on environmental challenges’ as one of the explicit topics that could be considered for a substantive protocol under the Convention.

Even though nobody doubts that the upcoming negotiations of the Convention will be extremely tough, the inclusion of the climate related elements in the Terms of Reference is a hopeful first step to push for a new approach to tax and climate.

Some countries, like Spain, Colombia, Pakistan or the Bahamas would have preferred for the terms to go further and strive for a much more comprehensive integration of tax policy and equitable climate action. These countries should be supported to not give up on their agenda in the upcoming negotiations.

Inspiration can be drawn from the Agreement on Climate Change, Trade and Sustainability (ACCTS). In this first-of-a-kind hybrid trade and environment agreement signed in 2024, four otherwise unrelated countries – Costa Rica, Iceland, New Zealand and Switzerland – agreed to live up to their climate ambitions and only wield their national power to create trade rules if consistent with climate targets. This includes the formal commitment to remove fossil fuel subsidies.

The ACCTS is purposely designed as an open plurilateral agreement, meaning that it’s agreed by a select few countries who are betting on the fact that other countries will join later, which they can do under the agreement at any stage. A ‘sustainable climate tax protocol’ in which an ever-expanding group of countries commit to creating national tax policy in line with pre-agreed principles of good taxation for climate finance may very well follow a same path.

The adoption of the UNFCITC along the lines set out in the terms of reference will be a massive boost in the race to meet the US$9 trillion climate finance challenge. Filling the climate finance gap requires uprooting the current system of international tax governance centred around the OECD/G20. It also requires urgent and universal progress in the fight against corporate tax abuse, the eradication of financial secrecy, the effective taxation of extreme wealth and the increase of cross-border assistance to enforce tax laws. These elements are front and centre in the terms and are expected to form the main focal point of next year’s negotiations.

At the same time, inclusive tax cooperation also implies establishing a fair and equitable international tax system which strengthens the Global South’s potential for domestic resource mobilisation, and, as a consequence, the reduced reliance on external climate financing pledges by the countries in the North.

A successful UNFITC negotiation can make this happen.

And, to be frank, it has to make it happen. The world has few options left to successfully face the climate challenge ahead. Countries must seize next year’s lifeline opportunity with everything they’ve got.

Image credit: President.az, CC BY 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Related articles

Disservicing the South: ICC report on Article 12AA and its various flaws

11 February 2026

What Kwame Nkrumah knew about profit shifting

The last chance

2 February 2026

After Nairobi and ahead of New York: Updates to our UN Tax Convention resources and our database of positions

The tax justice stories that defined 2025

2025: The year tax justice became part of the world’s problem-solving infrastructure

Bled dry: The gendered impact of tax abuse, illicit financial flows and debt in Africa

Bled Dry: How tax abuse, illicit financial flows and debt affect women and girls in Africa

9 December 2025

Two negotiations, one crisis: COP30 and the UN tax convention must finally speak to each other