Alex Cobham ■ How might today’s vote on the UN tax resolution go?

Today sees the vote by countries of the world on a resolution to move ahead towards a UN tax convention. Amongst the global media coverage, one article stood out. More or less all coverage reflects on the continuing opposition of some major OECD countries including the EU, UK and US, and focuses on the potential for a majority vote if the resolution is broadly supported by G77 members. The Guardian article instead claims that the resolution “is expected to fall at the last hurdle in a vote in New York on Wednesday”, because, it says, it “would need widespread agreement, including by the US and rich nations in Europe.”

This is not factually the case. A majority vote for the resolution could be delivered from G77 members alone, regardless of the stance of OECD members. However, it is true that OECD members have been successful in past cases (eg on debt negotiations) in preventing any movement simply by boycotting a process agreed by majority rather than by consensus. And it is notable that last year’s resolution on “Promotion of Inclusive and Effective Tax Cooperation at the United Nations” (A/RES/77/244) passed by consensus, with all countries agreeing not to require a vote.

But the precedent of OECD country boycotts does not imply, in this case, that the process would end – far from it. There are also precedents, such as on a recent digital governance resolution, of OECD countries opposing a resolution but then joining a process. In the case of the negotiations of a UN tax convention, there are three reasons to expect progress to follow from a majority vote.

First, the broad exclusion of most G77 countries from OECD processes means that there are multiple areas of tax cooperation that can be fruitfully negotiated among these UN member states alone. This includes, for example, possible agreement on automatic information exchange about financial accounts; on higher standards of beneficial ownership transparency, and on requiring public country by country reporting from multinational corporations operating in their jurisdictions.

In addition, G77 countries could move ahead with the creation of a framework for future negotiation of tax rules. And this is the second reason why OECD members are unlikely to boycott in practice. It was the simple threat of a few countries introducing digital sales taxes that led the affected, small group of US multinationals to force the US Treasury back to the negotiating table at the OECD, and produced the ‘BEPS 2.0’ process which has been running for 5 years now. If G77 countries were to begin negotiating a version of the G-24 proposal to abandon arm’s length pricing and move to a unitary taxation approach, with dramatic effects for the scale of profit shifting that could be achieved, the collective multinationals of the OECD would surely demand that their headquarters countries take a full part in the discussions.

Lastly, it is notable that the Africa Group resolution is carefully designed in this regard. Rather than launch straight into formal negotiations, the resolution envisages the creation of an inclusive, intergovernmental committee to set the terms of reference by August 2024. That process allows any country that opposed the resolution the opportunity to understand better what is on potentially on the table, and to assess whether their interests are better served by participating or boycotting. Given that OECD members suffer the great majority of the global revenue losses due to corporate tax abuse, the value of joining constructively at the outset may well be clear – both to OECD governments and their electorates.

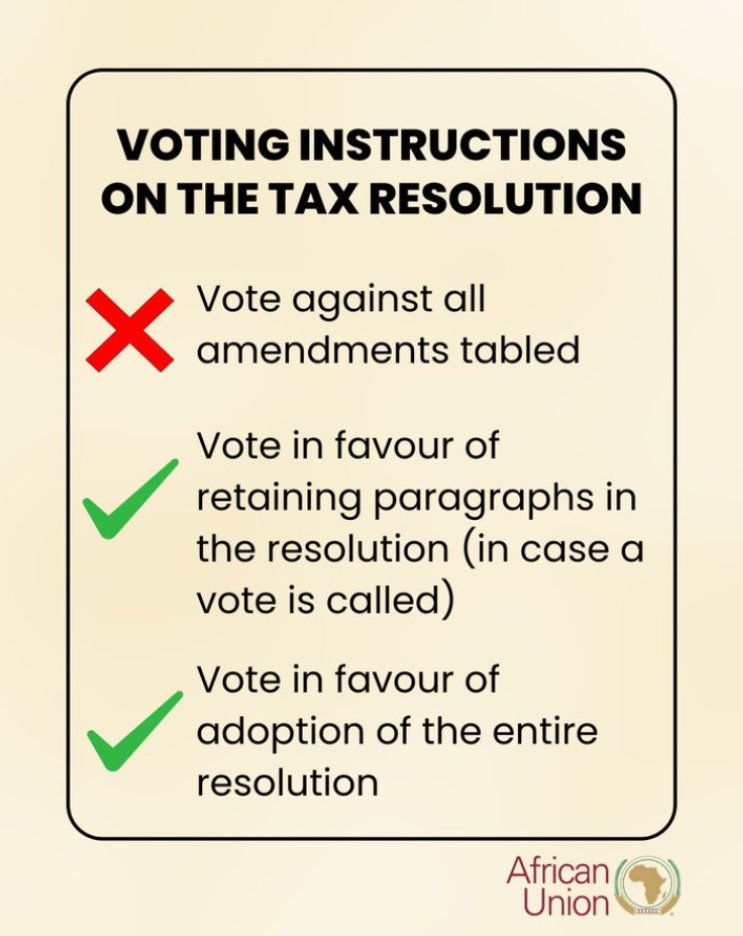

What can we expect in the vote? First, there will be a number of amendments to vote upon before the final resolution.

It is now known that the UK has tabled amendments to remove all reference to a framework convention. Were these adopted, the UN membership would be agreeing to begin negotiations on establishing a non-binding framework for future discussions on tax. The UK and EU have pushed this option insistently throughout the current process. Neither has been able to countenance entering into negotiations with the possibility of a legally-binding outcome on the table – that is, to make the question of whether the instrument being negotiated is a framework or a framework convention, a part of the negotiations itself. Leaving the exact instrument being negotiated to be part of the negotiations is not at all uncommon, and this blinkered refusal from the UK and EU has been a major obstacle to consensus.

There may be additional amendments at the last minute, from the EU or others. Last year for example, the US tabled a wrecking amendment that would have removed almost all substantive content from the Africa Group’s proposal – but when it was roundly defeated, the US and all others joined the consensus on the original resolution.

This year, it is rumoured that the US will insist on putting the whole resolution to a vote (with or without any agreed amendments). At this stage, it is of course difficult to predict the outcome. We cannot know how much pressure the US, EU and UK are putting on G77 members to abandon their support for the Africa Group – although it is known to be substantial. In addition, the OECD has been lobbying intensely both for the blockers to stand firm in opposition, and for newer members that are also G77 members – including Colombia, Chile, Costa Rica and Mexico – to distance themselves.

Nonetheless, there is quiet confidence that the G77 will bring broad support to bear. While there are likely to be evident exceptions such as Singapore (ranked in the top ten of the Corporate Tax Haven Index), the indications of support from across the world are growing. The desire of countries to have their voice heard on these issues is increasingly clear. The African Union has issued an explicit call for countries to vote with it.

And so the most likely outcome, at this point, seems to be the rejection of amendments to water down the Africa Group’s resolution; followed by a majority vote in favour, with a number of OECD countries in opposition.

That would leave the non-trivial matter of agreeing a budget at the UNGA 5th Committee in December – where the blockers might try again, by aiming to starve the process of funds. But the budget required for the next stage is set at less than $US2m, and at that point will surely be found in one way or another.

And so a majority vote later today will be enough for the world to enter into the entirely unprecedented process of genuinely, globally inclusive decision-making over international tax rules.

Related articles

The elephant in the room of business & human rights

UN submission: Tax justice and the financing of children’s right to education

14 July 2025

How the UN Model Tax Treaty shapes the UN Tax Convention behind the scenes

The 2025 update of the UN Model Tax Convention

9 July 2025

One-page policy briefs: ABC policy reforms and human rights in the UN tax convention

UN Submission: A Roadmap for Eradicating Poverty Beyond Growth

A human rights economy: what it is and why we need it

Do it like a tax haven: deny 24,000 children an education to send 2 to school

Urgent call to action: UN Member States must step up with financial contributions to advance the UN Framework Convention on International Tax Cooperation